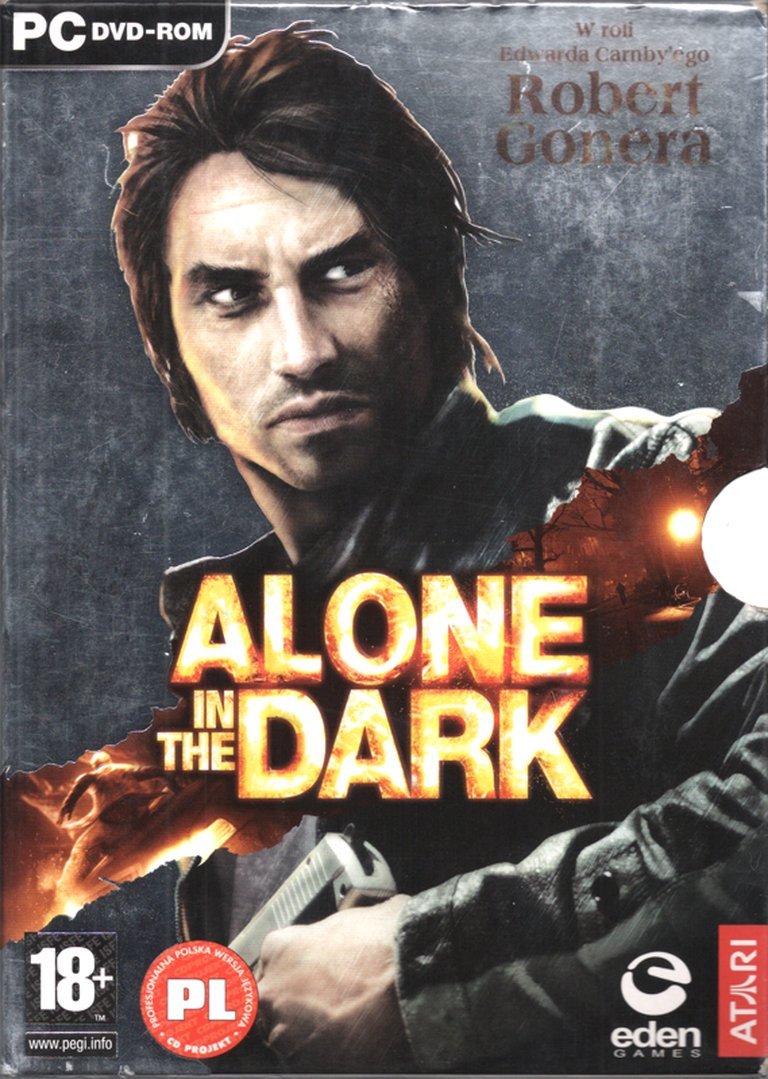

- Release Year: 2008

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Atari Interactive, Inc.

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Average Score: 61/100

Description

Alone in the Dark (2008) is a survival horror video game and the fifth installment in the iconic series, where players control the amnesiac private investigator Edward Carnby as he awakens in a New York City psychiatric institution, unraveling a sinister conspiracy involving ancient, otherworldly forces that threaten to consume the modern urban landscape of Central Park and beyond. Featuring innovative gameplay structured in DVD-like episodes with interchangeable first- and third-person perspectives, interactive environments where everyday objects become improvised weapons, and dynamic fire mechanics, the game blends puzzle-solving, exploration, and intense combat against grotesque creatures in a gripping tale of supernatural dread.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Get Alone in the Dark

PC

Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (58/100): Ambitious but inconsistent, frustrating but entertaining. Still an innovative adventure.

videogamer.com : At times Eden’s ambitious survival horror game touches on brilliance… but suffers from almost every longstanding gaming irritant and problem.

gamespot.com (65/100): If you can endure some vexing technical flaws, Alone in the Dark can be a clever, satisfying adventure.

ign.com : There are many genuinely inventive ideas at play… but few of them work as well as they should and most are failures.

imdb.com : This video game had plenty of potential and was even the most awaited Horror-Action game in 2008… tried too hard but failed on all aspects.

Alone in the Dark: Review

Introduction

In the flickering glow of a flashlight beam cutting through Central Park’s encroaching shadows, Edward Carnby emerges from amnesia into a nightmarish apocalypse, battling demonic fissures and possessed humanoids in a city unraveling at the seams. This is the visceral hook of Alone in the Dark (2008), a bold resurrection of a franchise that practically birthed the survival horror genre back in 1992. As the fifth mainline entry—often dubbed an informal sequel to the originals despite its loose ties—the game promised to drag the series into the next generation with physics-driven environmental interactions and a modern, urban dread. Yet, for all its revolutionary ambitions, Alone in the Dark stumbles through its own darkness, delivering flashes of ingenuity amid persistent technical frustrations. My thesis: This is a game of profound potential, a pivotal (if flawed) evolution in survival horror that innovates with fire and object manipulation but is ultimately undermined by clunky controls, inconsistent design, and a narrative that prioritizes spectacle over substance—cementing its status as a cult curiosity rather than a triumphant return.

Development History & Context

The 2008 Alone in the Dark emerged from a turbulent revival effort spearheaded by Atari Interactive, the rebranded Infogrames that had stewarded the series since its inception. Originally conceived as Alone in the Dark: Near Death Investigation, the project aimed to honor the franchise’s roots in H.P. Lovecraftian cosmic horror while adapting to the seventh-generation console era. Eden Games, a French studio known for racing titles like Test Drive Unlimited, took the reins for the PC, Xbox 360, and eventual PlayStation 3 versions, directed by David Nadal with producer Nour Polloni and lead designer Hervé Sliwa. Their vision was audacious: transform the tank-controls-and-puzzles formula of the originals into a free-roaming, physics-based survival horror experience emphasizing real-time environmental manipulation.

Technological constraints of 2008 loomed large. The Xbox 360 and PS3 demanded next-gen visuals, but hardware limitations—such as inconsistent frame rates and memory caps—challenged Eden’s use of the proprietary Twilight 2 engine, which powered dynamic fire propagation and ragdoll physics. Pre-release tech demos showcased these innovations: one demonstrated inventory mechanics like attaching glow sticks with tape for makeshift lighting; another highlighted fire’s realistic spread across objects, from tables to clothing. A third explored bullet impacts shattering furniture, while a fourth previewed enemies and their vulnerabilities. These demos, released between February and June 2008, built massive hype, positioning the game as a technical showcase akin to Half-Life 2‘s physics experiments.

The broader gaming landscape was a double-edged sword. Survival horror was thriving post-Resident Evil 4 (2005), with its over-the-shoulder action-horror hybrid dominating. Titles like Dead Space (2008) emphasized gore and zero-gravity tension, while the series’ own Alone in the Dark: The New Nightmare (2001) had echoed Resident Evil‘s fixed-camera puzzles. Eden sought to differentiate with episodic structure (mimicking DVD menus for chapter-skipping) and open-world elements in a destructible Central Park. However, parallel development by Hydravision Entertainment for PS2 and Wii versions—resulting in a more linear, first-person shooter variant—highlighted resource splits and platform fragmentation. Released amid the 2008 economic downturn, the game faced scrutiny: Atari’s aggressive push, including threats of lawsuits against negative preview sites like Gamer.nl for alleged piracy, underscored industry pressures for a blockbuster hit. Budgeted as a high-profile revival, it retailed at $60, but development delays (initially slated for 2007) led to a rushed Xbox 360 launch, with the PS3’s Inferno edition arriving months later with fixes like improved driving and camera controls.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Alone in the Dark‘s story unfolds across eight episodic chapters, blending occult conspiracy with apocalyptic horror in a narrative that echoes the series’ Lovecraftian origins while injecting biblical undertones. Protagonist Edward Carnby awakens amnesiac in a collapsing high-rise, post-exorcism, surrounded by occultists led by the fanatical Crowley. Escaping via crumbling corridors and possessed elevators, Carnby witnesses supernatural fissures—glowing rifts spewing demonic entities—devouring victims. He allies with Sarah Flores, a sharp-tongued art dealer, and Theophile “Theo” Paddington, his former mentor and exorcist, who reveals the Philosopher’s Stone: a Lucifer-forged artifact promising immortality but serving as a vessel for the Devil’s soul.

The plot propels Carnby and Sarah into a fissured New York City, crashing in Central Park—the epicenter of chaos. Theo’s suicide bequeaths the Stone’s half, tasking Carnby with unraveling its history via museum lore and underground puzzles. Revelations compound: Carnby’s immortality stems from 1938 events, tying him to alchemist Hermes Trismegistus, who guards the Stone’s counterpart. Crowley’s cult seeks to unleash Lucifer through a portal in Belvedere Castle’s depths. Climaxing in a choice-driven finale—sacrifice Sarah to Lucifer or let her become his vessel—the narrative branches into pyrrhic endings, underscoring isolation.

Thematically, the game grapples with legacy and damnation, reviving Carnby as a timeless “Shadow Hunter” haunted by his lineage’s curse. Central Park, reimagined as an alchemical labyrinth built by 19th-century occultists, symbolizes corrupted Eden—nature twisted by human hubris, mirroring Lovecraft’s indifferent cosmos. Biblical motifs (Lucifer’s fall, the “Path of Light”) contrast the originals’ voodoo and elder gods, adding Judeo-Christian weight but diluting cosmic dread. Characters shine unevenly: Carnby’s gruff, profanity-laced dialogue (“I’m used to it” in one ending) evokes noir isolation, voiced convincingly by James McCaffrey. Sarah’s emails provide exposition and warmth, humanizing the apocalypse, while Theo’s ghostly guidance adds pathos. Crowley, inspired by Aleister Crowley, embodies fanaticism, his taunts via texts heightening paranoia.

Yet, dialogue falters with clichés—overreliance on F-bombs for edginess—and plot holes, like Carnby’s unexplained century-spanning life. Pacing juggles spectacle (fissure chases) with lore dumps, but emotional beats, like Theo’s sacrifice, resonate amid the ruins. Overall, it’s a thematic deep dive into eternal recurrence, where personal isolation mirrors the series’ evolution from haunted mansions to urban Armageddon, though it prioritizes bombast over introspection.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Alone in the Dark loops around survival amid environmental chaos: scavenge resources, manipulate objects, solve physics-based puzzles, and combat via improvised means, all while managing health and inventory in real-time. Progression is linear yet semi-open in Central Park’s zones, divided into eight 30-40 minute episodes. Players can skip ahead with recap cutscenes, echoing TV serialization—a novel but underutilized feature that mitigates backtracking frustration.

Combat innovates but falters. Enemies—”Humanz” (possessed husks), “Ratz” (swarming rodents), “Vampirez” (bat-like flyers), and “Roots of Evil” (fiery tendrils)—vulnerable only to fire, demand creativity: ignite chairs for flaming clubs, combine fuel-soaked bullets for incendiary shots, or craft Molotovs from bottles and rags. The jacket inventory, accessed by Carnby peering inside, limits slots by category (projectiles right, tools left/center), enforcing scarcity—drop items to free space, or “favorite” combos (e.g., lighter + spray for flamethrower) for quick swaps. Melee swings via right-stick flicks feel visceral initially, with destructible environments (shoot a table leg for a torch). However, inconsistencies plague it: collision detection fails, letting enemies clip through walls; ammo scarcity turns fights into resource grinds; and first/third-person switching (melee third-person only, shooting first-person) disrupts flow, especially with sluggish turning.

Character progression is minimal—no levels or trees—but health mechanics add tension: wounds bleed (screen flashes red with heartbeat audio), healed via sprays or bandages, with deeper gashes requiring both. UI is intuitive yet intrusive: real-time inventory pauses nothing, forcing retreats from combat, while the episodic menu aids replays but exposes pacing gaps. Driving segments—hijacking taxis or cop cars amid fissure pursuits—leverage Havok physics for spectacular crashes but suffer arcade-clumsy handling (Eden’s racing roots notwithstanding), feeling like trial-and-error QTEs.

Innovations like fire’s propagation (spread via fuel trails, extinguish with water) and object combos (tape glow sticks to walls for persistent light) shine in puzzles—lure enemies with blood packs, electrocute foes via dangling wires. Flaws abound: buggy physics (forklifts jamming, doors resisting smashes), repetitive root-hunting (burn 20+ tendrils, stretching runtime), and AI that pathfinds poorly (enemies ignore fire until scripted). The PS3 Inferno refines this with 360° camera, better inventory, and exclusive Episode 6 content, but core issues persist. Ultimately, gameplay loops evoke survival’s desperation but drown in fiddliness, rewarding patience over polish.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Central Park, reimagined as a labyrinthine apocalypse, forms the game’s beating heart—a once-idyllic oasis warped into a fissure-riven hellscape of overgrown ruins, subway depths, and museum crypts. World-building draws from alchemical lore: the park as a 19th-century “Path of Light” ritual site, its Belvedere Castle hiding Lucifer’s portal, ties the urban setting to occult history. New York’s skyline crumbles in vignettes—fissures swallowing taxis, possessed crowds rioting—crafting a tangible dread of encroaching doom. Environmental storytelling via emails (Sarah’s research, Crowley’s taunts) and Theo’s ghostly narrations deepens immersion, evoking the originals’ mansion exploration but scaled to city-wide catastrophe.

Visual direction leverages Twilight 2’s strengths: dynamic lighting casts eerie shadows, with fire’s orange glow contrasting the park’s verdant decay. Textures pop on high-end PCs (detailed foliage, reflective puddles), and destructible elements—like shattering glass or buckling doors—enhance interactivity. Character models falter: Carnby’s scarred, leather-clad grit suits his anti-hero vibe, but animations stutter (jerky climbs, unnatural gaits), and facial expressions border on uncanny valley. The Xbox 360 version suffers tearing and frame dips; PC shines with tweaks. Art style blends realism with horror—glowing fissures pulse like veins, Humanz’ fissures mimic infernal wounds—fostering atmosphere, though pop-in and loading screens disrupt flow.

Sound design amplifies unease: Olivier Deriviere’s orchestral score, bolstered by The Mystery of Bulgarian Voices’ ethereal choir, swells from subtle piano dread to bombastic choirs during chases, evoking Silent Hill‘s menace without overkill. Virtual instruments mimic a live orchestra, with tracks like the haunting “Central Park Theme” underscoring isolation. Ambient audio excels—creaking ruins, distant screams, fissure rumbles—while enemy shrieks (Humanz’ guttural howls) heighten tension. Voice acting is solid: McCaffrey’s gravelly Carnby grounds the chaos, though supporting lines veer clichéd. SFX, like crackling flames or splashing dark liquid (a light-fearing hazard), integrate seamlessly, contributing to an experience where sound isn’t mere backdrop but a survival tool—torch batteries drain audibly, wounds pulse with heartbeats. Collectively, these elements forge a moody, immersive world that lingers, even if visuals occasionally falter.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its June 2008 launch (EU: June 20; NA: June 23), Alone in the Dark polarized critics and players, earning “mixed or average” scores: 58/100 on Xbox 360 (Metacritic), 55/100 on PC, dipping to 39/100 on Wii’s linear port. Praised for fire mechanics and puzzles (GameSpot’s 6.5/10 lauded “clever, satisfying adventure” despite flaws), it drew ire for controls, bugs, and repetition (IGN’s 3.5/10 called it “frustrating”). The episodic structure and jacket inventory intrigued (Eurogamer’s 7/10), but driving and AI baffled (GameSpy’s 2/5). Atari’s backlash—threatening lawsuits against low-scoring previews for “piracy”—ignited controversy, with sites like Gamer.nl defending legit copies and accusing selective embargoes. Famitsu scored PS3 at 26/40, Xbox 360 at 24/40.

Commercially, it succeeded modestly: 1.2 million units by July 2008, bolstered by limited editions (UK’s figurine/artbook/DVD/soundtrack bundle). The PS3 Inferno (November 2008) improved reception (69/100), adding camera tweaks and content, but couldn’t fully salvage the launch. Player reviews echoed divides: MobyGames’ 5.5/10 cited “frustrating but entertaining”; some hailed innovation, others decried “tedious” combat.

Legacy-wise, it influenced physics-driven horror (Dead Space‘s limb-severing echoed object manipulation) and episodic formats (The Walking Dead). As a bridge between old-school puzzles and modern action-horror, it revived Carnby for a new era—tying to 1938 lore—paving for Illumination (2015, panned) and the 2024 remake. Yet, its flaws symbolized rushed next-gen transitions, a cautionary tale amid the series’ foundational impact on Resident Evil. Cult status endures for tech demos’ prescience, influencing environmental interactivity in titles like The Last of Us.

Conclusion

Alone in the Dark (2008) is a Frankenstein’s monster of survival horror: stitched from revolutionary fire physics, clever inventory improvisation, and a thematically rich occult apocalypse, yet animated by clunky controls, buggy inconsistencies, and uneven pacing that hobble its ambitions. It honors the series’ legacy—pioneering dread since 1992—while struggling against 2008’s tech hurdles, delivering memorable set pieces (fissure escapes, root hunts) amid frustrations. For historians, it’s a snapshot of genre evolution; for players, a polarizing gem worth enduring for its sparks of brilliance. Verdict: A flawed 7/10—innovative but incomplete, deserving a revisit via Inferno or the upcoming remake, but not the definitive revival the franchise merited. In Carnby’s words, it’s a tale of being “used to it”—alone, in the dark, yet enduring.