- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: magnussoft Deutschland GmbH

- Developer: Darkage Software

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

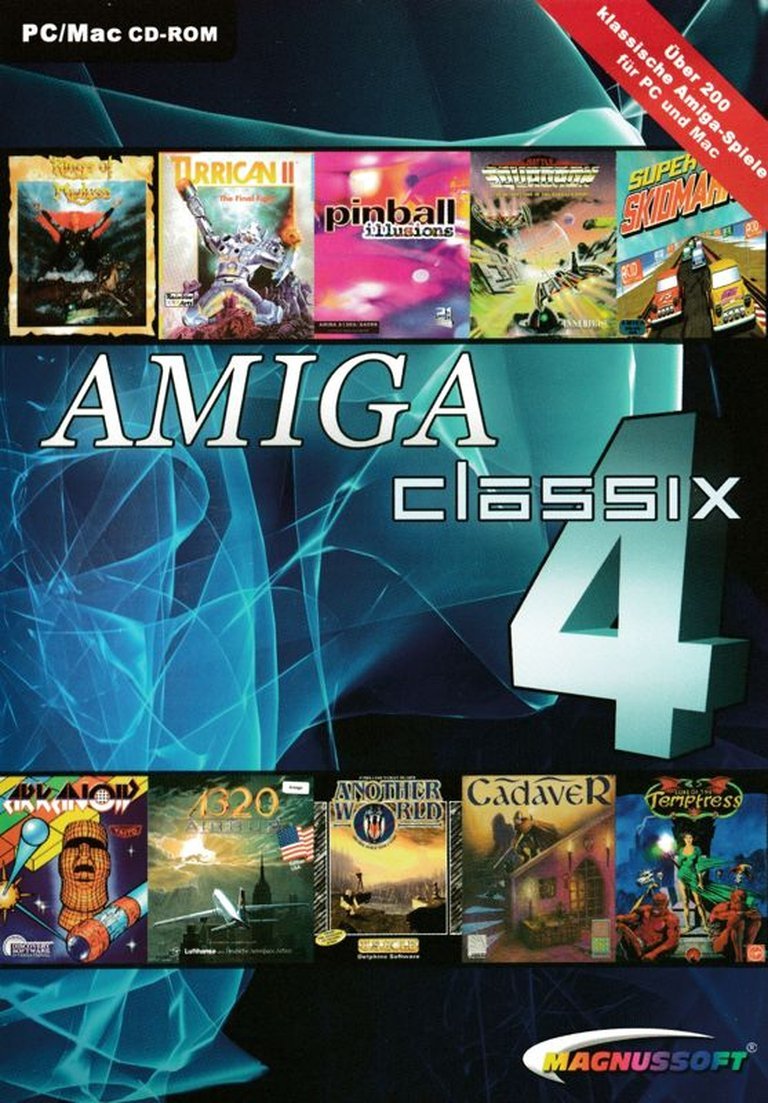

Amiga Classix 4 is a comprehensive compilation from the Amiga Classix series, featuring 127 full-version Amiga games and 66 additional demos emulated for modern Windows and Macintosh systems via the UAE emulator. It faithfully recreates the original Amiga experience, including authentic disk drive sounds and loading times, with most copy protections removed, and allows players to browse by genres such as Action, Adventure, Arcade, Sports, and Strategy & Sim for easy access to these retro titles.

Where to Buy Amiga Classix 4

PC

Amiga Classix 4: Review

Introduction

The Commodore Amiga, a culinary marvel of 16-bit computing, defined an era where graphical prowess and sonic richness were hallmarks of home gaming. Decades after its decline, the allure of its library persists, a siren call to retro enthusiasts and historians alike. Enter Amiga Classix 4, a 2004 compilation from Magnussoft Deutschland GmbH and Darkage Software, marketed as a portal to this legendary past. But does it deliver an authentic time capsule, or does it crumble under the weight of its own ambitions? This review delves deep into the compilation’s fabric, arguing that while Amiga Classix 4 is a flawed artifact, its core value lies in democratizing access to Amiga history—even if its packaging promises more than it fulfills. It is a tribute to preservation, tempered by commercial realities that mirror the Amiga’s own tumultuous legacy.

Development History & Context

Studios and Vision

Amiga Classix 4 was developed by Darkage Software, a German studio with a penchant for retro compilations, and published by magnussoft Deutschland GmbH, known for budget-friendly re-releases. This entry is the fourth in the Amiga Classix series, which began in 2001. The vision was clear: to curate the Amiga’s vast library and make it playable on modern Windows and Macintosh systems via emulation, specifically using the WinUAE emulator. Unlike its predecessors, which were full-priced, Amiga Classix 4 launched at a budget price point (under €15), signaling a shift toward accessibility over premium curation.

Technological Constraints and Emulation Challenges

The Amiga’s custom chipset—comprising the Agnus, Denise, and Paula—enabled groundbreaking visuals and audio in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Emulating this on early-2000s hardware required careful configuration. WinUAE, a freeware emulator, was pre-configured for each game, automating the complex settings that typically stymied novice users. However, the compilation aimed for authenticity by simulating original loading times and the distinctive sounds of floppy disk drives. This commitment to verisimilitude, while nostalgic, introduced friction: players endured blank screens and mechanical whirring that, as critic Xoleras noted, could become “increasingly getting boring.” Copy protections were mostly stripped, but three games retained them, a nod to preservation ethics that occasionally hampered playability.

Gaming Landscape of 2004

The early 2000s saw a surge in retro compilations, driven by nostalgia markets and the maturation of emulation technology. Amiga Classix 4 entered a space crowded with collections for the C64, NES, and arcade systems. Its unique selling proposition was the Amiga’s reputation for pushing hardware limits—games like Shadow of the Beast and Lemmings were benchmarks of their time. Yet, the Amiga’s commercial decline after Commodore’s 1994 bankruptcy meant its library was fragmented, requiring compilers to navigate licensing hurdles. Magnussoft’s approach, bundling emulators with games, was pragmatic but not without pitfalls, as marketing claims often outpaced the actual content.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

A Mosaic of Stories

As a compilation, Amiga Classix 4 does not present a unified narrative but rather a kaleidoscope of stories from the Amiga era. The included games span genres, each with distinct thematic preoccupations. Action titles like Stormlord (1989) and Cyberblast (1992) draw from fantasy and sci-fi tropes, pitting heroes against demonic legions or alien threats. Astaroth: The Angel of Death (1989) leans into dark fantasy, while Air Supply (1990) offers a Cold War thriller vibe. Adventure games, a strong suit for the Amiga, provide richer narratives: Another World (1991) by Éric Chahi is a minimalist sci-fi epic that uses rotoscoping for cinematic storytelling; Beneath a Steel Sky (1994) by Revolution Software presents a dystopian cyberpunk world with satirical depth. Strategy and simulation titles like UMS: The Universal Military Simulator (1987) or Rings of Medusa (1989) weave complex world-building into their mechanics, imagining geopolitical conflicts or dark fantasy realms.

Themes of Innovation and Constraint

Underlying these narratives is a reflection of the Amiga’s technological constraints. Games often used limited cutscenes or text-based exposition due to memory limits, leading to creative storytelling—such as Flashback (1992) with its rotoscoped animations or The Adventures of Maddog Williams (1991) with its comedic fantasy. The compilation inadvertently highlights how Amiga developers stretched hardware to convey emotion and plot, whether through the haunting atmosphere of Deliverance: Stormlord II (1992) or the satirical humor of P. P. Hammer and His Pneumatic Weapon (1991). These themes of resilience and ingenuity mirror the Amiga community’s own struggle to preserve its legacy.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Emulation as a Double-Edged Sword

The core gameplay loop in Amiga Classix 4 is defined by the WinUAE emulator, which is pre-configured for each title. This is a standout feature: as Xoleras praised, it eliminates hours of tinkering, offering one-click launches with optimized settings. Users can choose between mouse/keyboard or mouse/joystick controls, accommodating the era’s diverse input schemes. However, this ease comes with trade-offs. The simulated loading times and floppy drive sounds, while authentic, disrupt flow—a point of frustration echoed in reviews. More critically, the compilation’s handling of manuals is spotty; many games lack integrated documentation, forcing players to guess controls or consult external resources, which undermines accessibility.

Diversity and Inconsistency

With 127 full games and 66 demos spanning action, adventure, arcade, sports, strategy, and simulations, the compilation showcases the Amiga’s genre versatility. Gameplay mechanics range from the reflex-driven shooter Cybernoid (1988) to the strategic depth of Tactical Manager (1994) and the physics-based chaos of Super Skidmarks (1995). Pinball simulations like Pinball Dreams (1992) replicate table dynamics with impressive fidelity. Yet, inconsistency plagues the package. As critics noted, many “full version” claims are misleading—titles like Alien Breed: Tower Assault, Lemmings 2, and Turrican 2 are often demo versions with limited levels. This bait-and-switch erodes trust, though the sheer volume of playable content (around 130 full games, per Xoleras) still offers value for dedicated fans.

Innovative and Flawed Systems

The compilation innovates by categorizing games into genres within its menu, complete with screenshots and basic info (year, company, web links). This interface is user-friendly but relies on proper tagging; some games blur genre lines, like Boppin’ (1992), a puzzle game that might misfile. Control schemes vary wildly—some games support modern keyboards seamlessly, while others require precise joystick input that may not translate well. The inclusion of save states via F12 is a modern convenience absent in original Amiga titles, though purists might decry it as cheating. Copy protection removal is mostly thorough, but the three stragglers remind users of the compilation’s pragmatic compromises.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The Amiga’s Audiovisual Legacy

The Amiga’s custom chipsets enabled visuals that were revolutionary for the mid-1980s. Games in Amiga Classix 4 demonstrate this range: Pinball Fantasies (1992) uses multiple playfields and smooth scrolling; Cybernoid features parallax scrolling and detailed sprites; early 3D attempts like Zarathrusta (1991) showcase wireframe graphics. Even demos, such as those from the Amiga ClassiX series, highlight demoscene prowess with scrolling effects and music visualizers. The compilation’s art direction is a time capsule—pixel art from artists like those at Sensible Software (Cannon Fodder, not included) or The Bitmap Brothers (Speedball 2, not included) set standards for clarity and style.

Sound Design and Atmospheric Authenticity

Audio was the Amiga’s forte. The Paula chip delivered four-channel stereo sound, a novelty in an era of bleeps. Amiga Classix 4 preserves iconic chiptunes and tracker music: Battle Squadron’s title theme (composed by Ron Klaren, who contributed menu music) is a standout with its driving basslines; Lemmings demos feature memorable melodies. The simulated floppy drive sounds, while jarring to modern ears, evoke the physicality of Amiga loading—a sensory detail that enhances immersion for veterans but can grate over time. The compilation’s soundscapes range from the atmospheric dread of Another World to the whimsical tunes of Superfrog (1993), reflecting the platform’s diversity.

Cohesion Through Chaos

As a collection, Amiga Classix 4 lacks visual or auditory cohesion—games from 1987 to 1997 exhibit evolving aesthetics. Yet, this inconsistency is part of its charm, illustrating the Amiga’s technological evolution. The menu’s static screenshots and basic info provide context, but the real world-building happens in-game. Each title transports players to its unique universe, from the biblical fantasy of Stormlord to the managerial realism of Tactical Manager. The emulation’s fidelity ensures these worlds feel true to their source, even if the presentation feels dated by 2004 standards.

Reception & Legacy

Critical and Commercial Reception

Upon release, Amiga Classix 4 received mixed reviews. German magazines gave it scores ranging from 50% (PC Games) to 69% (PC Action), averaging 60%. Critics praised the low price, easy setup, and vast library but lambasted the misleading packaging—many high-profile games like Worms and Turrican 2 were demos, a fact omitted from the box. Player reception was warmer, with an average 4.0/5 on MobyGames, largely from nostalgic Amiga owners who appreciated the convenience. Xoleras’s user review crystallizes this dichotomy: “the easy menu system… is just great,” but “the advertisement… is really bad” due to demo prevalence. The compilation sold modestly, buoyed by the retro niche.

Influence and Preservation Efforts

Amiga Classix 4 is part of a broader preservation movement. By leveraging WinUAE and licensing agreements, Magnussoft helped safeguard games that might otherwise have been lost to obsolescence. It introduced these titles to a generation without access to original hardware, fueling interest in emulation communities like HOL (Amiga Hall of Light) and WHDLoad. The compilation’s approach—pre-configured emulation with optional tweaking—set a template for later collections like C64 Classix and Amiga ClassiX Remakes. However, its demo-heavy content sparked debates about transparency in retro compilations, influencing future releases to disclose version details more clearly.

Place in Video Game History

Historically, Amiga Classix 4 is a footnote in the Amiga’s afterlife. It embodies the platform’s “ what could have been” narrative—a powerful system curtailed by market forces, now celebrated through fan-driven preservation. The compilation does not reinvent gaming but serves as an archival tool. Its legacy is dual: it provides invaluable access to obscure titles like Aunt Arctic Adventure (1988) or Cardiaxx (1991), yet its commercial shortcuts highlight the tensions between preservation and profit. In the grand tapestry of video game history, it is less a landmark and more a reliable archivist, ensuring that the Amiga’s contributions—from cinematic adventures to sports simulations—remain playable for scholars and enthusiasts.

Conclusion

Amiga Classix 4 is a paradox: a lovingly assembled archive undermined by its own marketing. Its strengths are undeniable—a vast, genre-spanning library, intuitive emulation setup, and budget pricing that lowers barriers to entry. For the Amiga aficionado, it is a treasure trove, offering instant access to classics like Another World, Pinball Dreams, and UMS alongside forgotten gems. Yet, the decision to bury demos among full games, coupled with inconsistent manual support, leaves a bitter aftertaste. As a historical document, it succeeds brilliantly, capturing the Amiga’s creative zenith. As a consumer product, it demands vigilance. In the end, Amiga Classix 4 earns its place not as a perfect compilation, but as a crucial one—a flawed monument to a platform whose spirit of innovation still resonates, disk drive whirs and all.