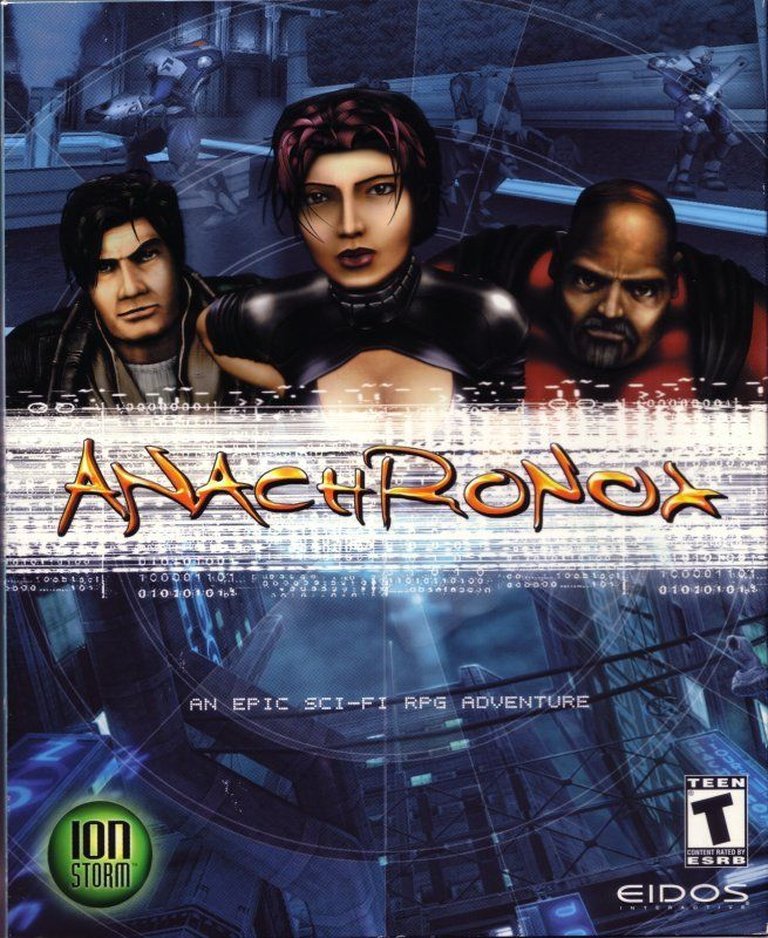

- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Acer TWP Corp, Eidos Interactive Limited, Noviy Disk, Sold Out Sales & Marketing Ltd., Square Enix, Inc.

- Developer: Ion Storm, L.P.

- Genre: Role-playing (RPG)

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Exploration, Mini-games, Party-based, Puzzles, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 79/100

Description

Anachronox is a sci-fi role-playing game set in a futuristic universe where players assume the role of Sly Boots, a down-on-his-luck private investigator who accepts a mysterious job offer that escalates into a cosmic threat against all existence. Blending Japanese-style RPG mechanics with Western elements, it emphasizes narrative-driven exploration, puzzle-solving, and humorous dialogue over combat, featuring a unique turn-based system with action bars, a party of eccentric allies with special abilities, and a focus on quirky situations and character development.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Anachronox

Anachronox Free Download

Anachronox Cracks & Fixes

Anachronox Patches & Updates

Anachronox Mods

Anachronox Guides & Walkthroughs

Anachronox Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (79/100): Past the technical issues and bland combat system is a universe that’s worth exploring.

interpop360.com : big ideas delivered with deadpan confidence.

Anachronox Cheats & Codes

PC

Enable debug mode by editing the Default.cfg file in \Anachronox\anoxdata\configs\ to set ‘debug 1’ to 1. During gameplay, press the ~ (tilde) key to open the console and enter cheat codes.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| invoke 1:86 | Unlocks cheat menu |

| battlewin | Win battles instantly |

| noclip | No clipping mode |

| timescale | Modify game speed; use with number parameter (e.g., 0.1-0.9 for slower, 1 for normal, >1 for faster) |

| map | Change map; requires map name as parameter |

| exec noxdrop | Unknown function |

| exec noxdrop_ai | Unknown function |

| exec bed | Unknown function |

| exec envshot | Unknown function |

| invoke 87:3035 | Grants a cobalt crawler |

| invoke 30:2000 | Grants flower petals |

Anachronox: The Unlikely Messiah of Cinematic RPGs

Introduction: A Galaxy of Potential, A Universe of Heart

In the pantheon of cult video game classics, few titles wear the badge of “brilliant failure” with as much defiant pride as Ion Storm’s 2001 sci-fi RPG, Anachronox. Emerging from the same Dallas studio that infamously birthed the debacle Daikatana, this game arrived not with a roar, but with a whimper—shipped under a cloud of corporate pressure, buried by minimal marketing, and overshadowed by its studio’s implosion. Yet, to dismiss Anachronox as merely a footnote in gaming history is to miss its profound, if fragmented, genius. It is a game thatbetrays its own troubled birth through visible seams and unfinished corners, yet within those seams burns a creative fire so intense it can still warm the player two decades later. My thesis is this: Anachronox is not a good role-playing game by traditional mechanical standards; it is, instead, a singularly great interactive narrative and comedic experience whose radical, character-first design philosophy made it a decade ahead of its time. It failed as a commercial product but succeeded as a proof-of-concept for a kind of story-driven, humor-infused adventure that would later become a staple of successful indie RPGs and narrative games. Its legacy is not in the games it directly influenced, but in the DNA it contributed to the evolving language of interactive storytelling.

Development History & Context: ambition Under Siege

The story of Anachronox is, in itself, a saga worthy of its own sci-fi epic. It was born from the mind of Tom Hall, the iconic designer behind Commander Keen and co-creator of Doom, who famously conceived the core premise in his shower, necessitating a whiteboard and notepads throughout his house to capture the deluge of ideas. Hall’s vision was colossal: a 460-page design document outlining a universe of “turbulent story with a roller coaster of emotion,” aiming to make players truly feel for its characters, to “answer the question, ‘Can a computer make you cry?'” This was to be a “Campbellian” myth, deeply personal, with characters that were “facets of his childhood.”

Technologically, the team chose id Software’s Quake II engine, a decision that would haunt them. The engine was fundamentally built for fast-paced FPS combat, not the complex character interactions and cinematic camera work Hall desired. The team’s solution was a Herculean series of modifications: they added 32-bit color support (massively expanding the palette), implemented custom vertex animation for emotive facial expressions and lip-syncing, created a powerful spline-based camera system dubbed “Planet,” and built a custom scripting language called APE (Anachronox Programming Environment). These were not minor tweaks; they amounted to a near-total engine overhaul, allowing for the sweeping, film-like cutscenes that would become the game’s most celebrated feature. As one developer noted, “Quake3 is Quake2 plus some really cool stuff. Anachronox is Quake2 plus some really cool stuff.”

The development timeline was a tragicomedy of delays and dysfunction. Initially announced for Q3 1998, the game slipped repeatedly. Eidos Interactive, having funded the project alongside Daikatana as part of a three-game deal, grew increasingly impatient. After Ion Storm exhausted its initial $13 million budget, Eidos bought a controlling stake and installed new management to contain costs and speed up the lethargic progress. The team size fluctuated; key members like lead level designer David Namaksy and lead programmer Joey Liaw departed for other opportunities. Internal strife, documented in leaked emails, further eroded morale. The final, crushing blow was the studio’s corporate strategy: to meet release deadlines and recover costs, a decision was made to slash approximately half of the completed game. This culled content—meant for a sequel—was never repurposed, leaving massive plot threads, entire planets, and character arcs on the cutting room floor. The Dallas office closed mere days after the game’s June 2001 release. The “labor of love” was, in the end, a corporate casualty.

The gaming landscape of 2001 was dominated by the fizzy, turn-based JRPGs of the PlayStation 2 (Final Fantasy X) and the deep, stats-heavy Western CRPGs of the PC (Baldur’s Gate II). Anachronox attempted an awkward, unprecedented hybrid: a console-style JRPG structure built for PC, with a focus on dialogue and exploration over combat, all wrapped in a cyberpunk-noir aesthetic. It was a game caught between continents, genres, and corporate realities.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Heart of the Matter

If Anachronox is remembered for one thing, it is its story and characters—a dense, funny, and surprisingly emotional tapestry that stands as one of the most original sci-fi narratives in gaming.

The Plot: The premise is classic noir with a cosmic twist. Sylvester “Sly Boots” Bucelli is a down-on-his-luck private investigator on the slum-planet Anachronox, drowning in debt to a mobster named Detta. His routine case to find a MysTech shard (mysterious alien artifacts) for the eccentric Grumpos Matavastros explodes into a galaxy-spanning conspiracy. The destruction of the scientific haven Sunder reveals that all MysTech has awakened, and that the universe is fatally unbalanced. A cosmic “Big Bounce” theory dictates that the universe is doomed to a premature Big Crunch because matter from a previous universe is being injected into this one. The forces of “Order” created MysTech to stop the forces of “Chaos,” who seek to escape to the previous universe and erase the current one from existence. Sly’s quest becomes a race to seal the gate to the past universe, a journey that forces him to confront the psychic poison of his own past.

The Characters: This is where the writing truly sings. The party evolves from the solitary, cynical Sly and his sarcastic robot PAL-18 into a found family of delightful misfits, each a subversion of a trope:

* Grumpos Matavastros: A 71-year-old, profoundly grumpy scholar whose “World Skill” is “Yammer”—a hilarious, relentless torrent of complaint that eventually forces NPCs to cave.

* Dr. Rho Bowman: A brilliant scientist branded a heretic for her book MysTech Awake!, whose scientific rationality clashes with the absurdity around her, producing gold like her subplot about appreciating “art” with a door.

* Democratus: The ultimate surrealist twist—an entire planet, fed up with its own bureaucratic, ring-dwelling High Council, shrinks itself to human size and joins the party as a literal, talking world. Its passive-aggressive commentary on democracy is a constant highlight.

* Stiletto Anyway: Sly’s ex-partner and flame, a stealthy assassin with a sharp tongue and a sharper blade, whose relationship dynamics with Sly and the holographic Fatima are complex and mature.

* Paco “El Puño” Estrella: A washed-up superhero, his comic book series canceled, now an alcoholic. His solo chapter is a poignant, blackly comic look at faded glory and rediscovered purpose.

* PAL-18: Sly’s childhood robot assistant, whose “hacking” mini-game is a pipe-dream puzzle, and whose developing personality and loyalty provide the game’s emotional core.

The NPCs are equally vivid. The game is peppered with minor characters who feel lived-in, delivering lengthy, often hilarious monologues on politics, religion, or their dislike of your appearance. The world breathes because its inhabitants are allowed to be weird and talkative, a direct repudiation of the functional, quest-giving NPCs common in RPGs.

Themes & Humor: Hall’s signature style—a blend of Monty Python, Douglas Adams, and Terry Pratchett—permeates every line. The humor is not mere joke-telling; it is baked into the world’s fabric. It’s in the narrative itself (a planet as a party member), in the dialogue (Sly’s “science language” scene is legendary), and in the visual gags (the Dopefish cameo, the Deus Ex reference “Deus Sex”). Crucially, the humor never undercuts the genuine pathos. The destruction of Sunder is treated with appropriate gravity, and Rho’s trauma, Sly’s guilt over Fatima’s death, and Paco’s existential crisis are played straight. The game’s true theme is confronting the “poison of the past” (the meaning of Anachronox), and the journey is as much about emotional catharsis as cosmic salvation. The tragic, revelatory flashback sequence detailing Sly and Fatima’s fatal car chase is a masterpiece of in-engine storytelling that would rival any cinematic.

The Flawed Brilliance: The narrative’s greatest weakness is a direct result of the cuts. The final act feels rushed. The betrayal of Grumpos as a “Dark Servant” is a fantastic twist, but it happens with scant development, and the true finale—the assault on the gate—is entirely absent, ending on a literal “to be continued” cliffhanger that can never be resolved. The ambitious, 460-page mythos was truncated, leaving tantalizing threads (the full nature of Chaos/Order, the fate of Krapton) forever dangling.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Bridge Too Far?

Anachronox’s gameplay is its most divisive element, a hybrid system that satisfies neither hardcore Western CRPG nor JRPG purists but carves a narrow, often frustrating, middle path.

Exploration & Adventure: The game’s primary loop is exploration and dialogue, more akin to a point-and-click adventure than a traditional RPG. Areas are beautifully realized 3D hubs (the twisted architecture of Anachronox’s Bricks slums, the vertiginous walkways of Sender Station) but are fundamentally linear in progression. You are funneled from one NPC to the next, solving simple puzzles that almost always involve “find X for Y” or “use character Z’s special skill.” The sense of discovery is limited by this rigid design; the vast, atmospheric spaces are largely decorative backdrops for prescribed sequences.

Character Progression & World Skills: Each party member has a unique “World Skill” (Boots: Lockpicking, PAL: Hacking, Rho: Analysis, etc.) used to solve environmental puzzles. These skills can be upgraded to “Master” level by finding a master. This system is clever in theory, encouraging backtracking, but often feels like a gatesim—a door is literally labeled “requires Master Lockpicking,” removing any sense of organic problem-solving. The RPG stat system uses qualitative descriptors (“Poor,” “Excellent”) instead of numbers, a deliberate design choice by Hall to demystify progression, but it makes leveling feel inconsequential.

Combat: The battle system is a transparent homage to Chrono Trigger and Final Fantasy‘s Active Time Battle (ATB). Enemies are visible on the map (no random encounters). Each character has an ATB gauge that fills in real-time; when full, they can execute a command: Attack, Move, Use Item, Cast MysTech, or use a BattleSkill. The ability to move characters on the battlefield is a notable Western twist, adding a layer of positioning strategy rarely seen in contemporaneous JRPGs.

However, combat is the game’s weakest link. It is consistently, achingly easy for the vast majority of the game, requiring minimal strategy. The “Bouge” bar for BattleSkills and the “NRG” for MysTech add resource management, but battles rarely tax the player’s resources. The system feels like a mandatory, low-stakes interlude between the “real” gameplay of exploring and talking. The “Limit Break”-style “Super Move” is visually spectacular but overused and under-challenged.

MysTech (Magic) System: MysTech is a fascinating, deep system in theory. Colored bugs are placed in an “Elementor Host” to create custom spells of various elements (green for poison, red for fire, etc.). The potential for player-driven spellcraft is immense. In practice, it’s largely irrelevant. Pre-found, high-level MysTech slabs are almost always superior to anything the player can cobble together, rendering the crafting minigame a tedious optional deep dive. The system’s potential remains unfulfilled, another victim of the cut content.

Minigames & “Filler”: The game is littered with minigames. Each World Skill has its own (Boots’ lockpicking is a decent timing puzzle; PAL’s hacking is a frustrating pipe-maze). There are fully playable arcade cabinets (Bugaboo, a Galaga clone; Pooper, a Pac-Man clone) and on-rails shooter sequences borrowed from Rebel Assault. These are a mixed bag: charming references that quickly become repetitive chores required to progress. They exemplify the game’s struggle to pad its adventure-core with “gameplay,” often breaking narrative momentum.

The Fatal Flaw: Linear Passivity. The most damning critique, echoed in many reviews, is the game’s extreme linearity. Despite the size and beauty of its worlds, the player has almost no agency. The path is a single, narrow corridor. Quests are not discovered through exploration but dictated by NPC dialogue trees. There is no meaningful choice or consequence. You cannot solve problems in alternative ways; there is one designated solution. This anti-emergent design is antithetical to the “living, breathing world” the atmosphere promises, making the experience feel like a beautifully painted railroad.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Masterclass in Atmosphere

(The following analysis synthesizes information from MobyGames specifications, reviews, and Wikipedia development notes.)

Visual Design & Engine Mastery: That Anachronox runs on the Quake II engine is a staggering technical and artistic achievement. The team’s modifications—expanded color palette (avoiding the engine’s typical murk), advanced particle effects for plasma and magic, and the revolutionary “Planet” camera system—transformed the tech. The result is a world of breathtaking scale and vibrant, coherent artistry. The levels are not just large; they feel architecturally sound and densely packed with detail. The slums of Anachronox’s Bricks, with their Escher-like impossible structures and gravity-defying walkways, are iconic. The pristine, snow-swept vistas of Sunder, the fiery temples of Hephaestus, and the bureaucratic surrealism of Democratus’s ring-world are all instantly recognizable and thematically perfect.

The character models are low-polygon (500-700 polys for mains), but the team used texture work and, crucially, the facial deformation system to inject immense personality. Characters emote through subtle eyebrow raises, smirks, and shifts in their mouth geometry. This, combined with the superb voice acting, creates a rare sense of connection. The blocky models are not a failure of the era but a deliberate, successful stylistic choice that lends the game a timeless, slightly cartoonish quality that matches its humor. The “dated” graphics complaints, while valid from a pure polygon-count perspective, fundamentally misunderstand the artistic cohesion on display.

Sound Design & Music: The audio is a point of consistent, high praise across critical and player reviews. The voice acting is exceptional, with each character’s performer perfectly capturing their essence—from Tom Hall’s own, perfectly grating turn as PAL-18 to the weary cynicism of Sly and the manic energy of Grumpos. The delivery is natural, nuanced, and frequently hilarious.

The musical score, composed primarily by Will Nevins and Darren Walsh with additional work by Bill Brown, is a dynamic, genre-hopping masterpiece. It swells from atmospheric, ambient synth during exploration to funky, swinging blues in bars (reflecting Hall’s “forties bluesy swing” vision), to chilling industrial and metal during moments of dread. The main theme is iconic. A minority of reviewers found it repetitive or cheesy, but the consensus is that the soundtrack is a perfect, emotive complement to the shifting tones of each planet and story beat. The use of MP3 format allowed for high-quality, diverse tracks, a technical boon for the time.

Cinematography & Machinima: The in-game cutscenes are Anachronox‘s crown jewel and its most influential legacy. Directed by filmmaker Jake Hughes, they use the “Planet” camera system to produce shots—sweeping pans, dramatic dolly zooms, intense close-ups—that were unprecedented in a real-time game engine. Characters emote and lip-sync with a fluidity that made the game feel like a playable movie. The editing is crisp, the pacing cinematic. This wasn’t just exposition; it was directed. The critical and fan acclaim was universal, with the compiled “Anachronox movie” winning Best in Show at the 2002 Machinima Awards. It demonstrated that a game engine could be a legitimate filmmaking tool, a concept that would later blossom with the rise of machinima and modern narrative direction in games like The Last of Us.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult Classic’s Journey

Critical Reception: Critics largely adored the game. It holds an 80% average on MobyGames from 48 professional reviews. The praise was nearly unanimous for its writing, characters, humor, world-building, and cinematic presentation. Computer Gaming World‘s 4/5 review summed it up: “ANACHRONOX is clearly a good game. It has an interesting and well-paced story, excellent dialogue and characters, and fun gameplay.” GameSpot (78%) noted its successful adaptation of the console formula: “It manages to stay true to its console roots while modifying the formula in a few key areas, not the least of which is the addition of plot and dialogue not translated from Japanese.”

The criticisms were consistent and pointed: the graphics, while artistically sound, were technically behind the curve; the combat was simplistic and often too easy; the game was buggy at launch (necessitating fan and unofficial patches); and the linearity was a significant design flaw. Eurogamer‘s 7/10 review captured the ambivalence: “A flawed classic, with moments of true genius marred by bugs and rough edges which could really have used a few more months of polishing.”

Commercial Performance & The Daikatana Shadow: Sales were abysmal. The game’s troubled sibling, Daikatana, had already vaporized Ion Storm’s credibility and consumer goodwill. Eidos, disillusioned, provided almost zero marketing. The game arrived with little fanfare in a crowded summer 2001 release slate. Its commercial failure was almost a foregone conclusion, a tragic endpoint to a studio that once symbolized developer hubris. As one player review starkly stated: “Had it not been for ‘that other Ion game’ Anachronox would have sold immensely better.”

Evolving Legacy: Over the years, Anachronox‘s reputation has undergone a profound rehabilitation. It is no longer seen as a failed product but as a beloved, deeply personal cult classic. Its Moby player score is a strong 4.0/5. Reviews from 2005-2017 are notably more reflective and appreciative, acknowledging its flaws but emphasizing its unique soul. Mystery Manor‘s 2005 review perfectly captures this shift: “If you missed it the first time around, I strongly recommend getting a copy now… Anachronox manages to bridge the gap between [RPG and adventure] genres, melding them seamlessly.”

Its influence is subtle but significant:

1. Narrative-Centric Design: It predated the “Walking Simulator” and narrative-adventure boom by proving that a game could be compelling primarily through witty writing, character depth, and world-building, with traditional gameplay as a secondary concern. Games like The Blackwell series or Primordia echo its adventure-RPG hybrid spirit.

2. Cinematic Ambition: Its in-engine cinematography set a new standard for visual storytelling within a game’s own assets. This directly influenced the machinima movement and raised expectations for seamless, integrated cutscenes in RPGs.

3. Comedy in RPGs: Its successful, pervasive humor—unafraid of being smart, referential, and bizarre—paved the way for later comedy-focused RPGs like The Bard’s Tale (2004) and the Borderlands series’ tone.

4. The “Lost Cause” Mythology: Its development saga—ambition curtailed by corporate meddling and time—became a cautionary tale and a rallying cry for developers advocating for creative control and realistic timelines. It is the ultimate “what could have been” game.

It remains an essential artifact for understanding the evolution of story-driven games, a testament to what can be achieved when a writer-designer’s vision is given (almost) free rein, even within a straitjacket of corporate and technical constraints.

Conclusion: A Flawed Masterpiece, A Permanent Imprint

To play Anachronox in 2024 is to engage with a ghost. It is a game that feels simultaneously confident in its quirky vision and painfully aware of its limitations. Its combat is a rote chore. Its linearity is a straitjacket. Its cut content leaves its epic story frustratingly incomplete. Its technical rough edges—the occasional crash, the loading zones—are the audible seams of its rushed birth.

And yet. To dismiss it on these grounds is to miss the point entirely. Anachronox is not about the game in the sense of mechanical challenge or open-ended freedom. It is about the experience—the experience of living in a universe brimming with absurd, memorable life; of laughing aloud at PAL’s “Bitch!” or Grumpos’s endless gripes; of being moved by Rho’s scientific wonder or Paco’s melancholic fall from grace; of marveling at a camera swooping through a digital city as a story unfolds with cinematic grace.

It is a game that understood, years before it was common, that characters and dialogue are not ancillary to gameplay but can be its primary driver. It prioritized feeling over friction, humor over heroics, and personality over polish. Its heart was, and is, indisputably in the right place.

Its place in history is secured not as a benchmark of technical excellence or genre-defining innovation, but as a beloved, deeply personal artifact of a specific time and a singular creative mind. It is the Citizen Kane of cult games: structurally imperfect, commercially unsuccessful, but so rich in invention, so full of heart and audacious ideas, that it casts a long, indelible shadow. Anachronox did not save the RPG genre. Instead, it saved a piece of its soul—a piece about friendship, regret, and finding the extraordinary in a universe full of colorful, talking planets and sock-puppet philosophers. For that, it is forever a classic.

Final Verdict: 9/10 – An Imperfect, Irreplaceable Gem. A must-play for any student of game narrative, comedy writing, or the history of developer-driven projects. Play it for the characters. Play it for the jokes. Play it to see what a game with a soul looks like, even when its body is held together by hope, duct tape, and the echoes of a dream that was cut short.