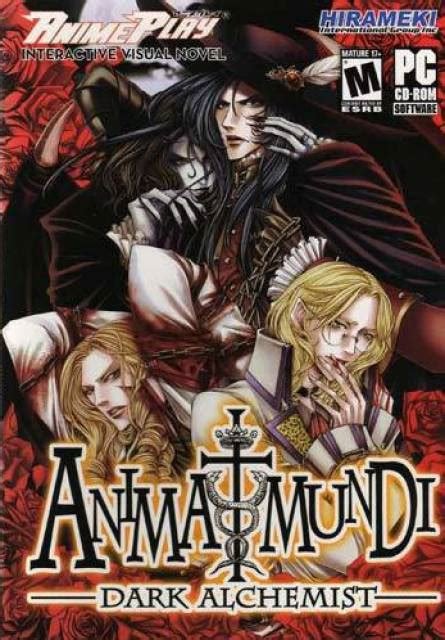

- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Karin Entertainment Hirameki International Group Inc.

- Developer: Karin Entertainment

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Choice-based, Item collection, Visual novel

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

Animamundi: Dark Alchemist is a gothic horror visual novel set in the fantasy kingdom of Hardland. It follows Count Georik Zaberisk, a former royal physician who resigns to care for his sister Lilith; after she is wrongfully accused of witchcraft, beheaded, and burned by villagers, Georik finds her head still alive and turns to forbidden alchemy to restore her body. Players navigate a dark narrative with timed choices and item collection to achieve multiple endings, uncovering horrific truths about the kingdom, colleagues, and themselves.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Animamundi: Dark Alchemist

PC

Animamundi: Dark Alchemist Free Download

Animamundi: Dark Alchemist Mods

Animamundi: Dark Alchemist Guides & Walkthroughs

Animamundi: Dark Alchemist: A Cult Gothic Horror Visual Novel’s Tormented Legacy

Introduction: A Beheading That Wouldn’t Die

In the vast, often-overlooked archives of mid-2000s visual novels, few titles carry the peculiar, tormented legacy of Animamundi: Dark Alchemist. Emerging from the shadows of a niche Japanese developer and onto the limited Western stage via a notoriously censored localization, this game is less a mainstream phenomenon and more a whispered secret among connoisseurs of gothic horror and narrative-driven gaming. Its premise—a noble physician’s desperate quest to reanimate his beheaded sister through forbidden alchemy—is a premise drenched in transgressive body horror and Faustian despair. This review posits that Animamundi is a fascinating, deeply flawed artifact: a game whose artistic ambitions in sound, voice, and macabre storytelling are repeatedly undermined by technical negligence and cultural bowdlerization, yet which persists as a crucial, if painful, case study in the perils and potentials of localized visual novels. Its true significance lies not in its polished execution, but in the raw, unfiltered darkness of its core concept and the controversial journey that concept undertook to reach an English-speaking audience.

Development History & Context: The Shadows of Karin Entertainment

Animamundi: Dark Alchemist (known in Japan as Anima Mundi: Owarinaki Yami no Butō, or “Anima Mundi: The Endless Dance of Darkness”) was developed by Karin Entertainment, a studio that operated with minimal international profile, primarily producing visual novels for the Japanese PC market. The game’s original 2004 release was thus destined for obscurity outside its home territory. Its arrival in the West was orchestrated by Hirameki International Group Inc., a publisher that, during the mid-2000s, carved out a peculiar niche localizing Japanese visual novels—often dating sims or niche titles—for the North American and European markets, primarily via their “AnimePlay” line of DVD-ROMs for PC and Mac.

This era was one of transition and tension for visual novels in the West. Mainstream awareness was virtually non-existent; distribution was physical, clunky, and expensive. Hirameki’s approach was a double-edged sword: it provided official, translated access to titles that would otherwise remain inaccessible, but often with significant compromises. The technological constraints were notable—games were typically built on older engines like Adobe Flash (as later sources confirm for this title), resulting in fixed 640×480 resolutions, static sprite-based visuals with minimal animation, and simple point-and-select interfaces that felt archaic even at the time. For Animamundi, these constraints framed a narrative of profound darkness within a technically unimpressive package. The gaming landscape of 2005-2006 was dominated by the rise of online distribution (Steam was nascent) and the maturation of genres like the survival horror (Silent Hill, Resident Evil) and the narrative adventure (Fahrenheit, The Longest Journey). Animamundi arrived not as a competitor, but as a curiosity from an alien genre, a gothic horror visual novel in a market hungry for interactive stories but largely unaware of Japan’s rich tradition of them.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Faustian Bargain in Hardland

The narrative of Animamundi is its undeniable, spine-tingling core. It is a story of grief, transgression, and the monstrousness of love.

Plot Structure & Core Conflict: Count Georik Zaberisk, a brilliant and respected Royal Physician to the King of Hardland, relinquishes his post to care for his younger sister, Lilith, a girl of delicate health and innocent disposition (noted for her love of animals and Gothic Lolita fashion). This act of familial devotion becomes his undoing. While Georik is away accepting a new post in the capital, a superstitious mob, suspecting Lilith of witchcraft, storms their manor. They burn her body and decapitate her. Georik’s return is a descent into hellish disbelief, culminating in the grim discovery: Lilith’s severed head remains alive, conscious, and pleading. This grotesque rupture of natural law forces Georik into the ultimate taboo. He turns to alchemy, an art strictly forbidden in Hardland, undertaking a desperate, clandestine research project to restore his sister’s body. This quest immediately draws him into pacts with damned forces, most notably a contract with the devil Mephistopheles.

The plot is not a simple recovery mission. It is a labyrinthine descent. Georik’s research, conducted in the city under the nose of his former colleagues, forces him to acquire forbidden ingredients, navigate a black market for anatomical parts run by the grotesque Francis Dashwood (a member of the secret Hell-Fire Club), and consult with the ambiguously mystical spirit medium Jan Van Ruthberg. Simultaneously, he must maintain a facade of normalcy among his aristocratic circle: his inventor friend Count St. Germant (Lilith’s fiancé), the devout Captain of the Royal Guard Viscount Mikhail Ramphet, and the sinister court alchemist Bruno Glening, who covets a pact with Mephistopheles that the devil refuses. The narrative masterfully weaves personal tragedy into a grand conspiracy, suggesting the rot in Hardland’s society—its superstition, its hidden occult knowledge among the elite, its capacity for brutal violence—is directly responsible for Lilith’s fate.

Themes in Extremis:

* The Monstrousness of Love: Georik’s love for Lilith is the catalyst for his utter moral and physical degradation. His actions are sympathetic yet increasingly monstrous; he becomes a body-harvesting alchemist, trafficking in the same kind of horrific violation perpetrated by the mob. The game asks: how far will one go for love, and at what point does the savior become the monster?

* Forbidden Knowledge & Transgression: Alchemy serves as the perfect metaphor for science divorced from ethics. It is a systematic, almost academic pursuit that requires acts of profound violation (the acquisition of specific body parts from the living or freshly dead). This critiques both blind religious superstition (the villagers) and hubristic, amoral rationalism (Glening’s ambition).

* Body Horror & Identity: Lilith’s existence as a severed head is the ultimate body horror. Her character, voiced with heartbreaking vulnerability by Yui Horie, represents innocence trapped in a state of profound violation. The quest to restore her body is not just a medical procedure but an attempt to restore her personhood, her “wholeness” in a society that has already fragmented her.

* Faustian Bargain & Corruption: The contract with Mephistopheles is the narrative’s dark heart. It is not a mere plot device but a gradual corruption. Mephistopheles, voiced with chilling, amused detachment by Hiroki Yasumoto, is a manipulating presence. The player is constantly aware that Georik’s salvation is predicated on his soul’s damnation, a classic theme rendered with visceral, personal stakes.

Character Dynamics: The supporting cast is not mere window dressing. St. Germant represents理性 (rationality) and technological progress, yet is powerless against the supernatural. Mikhail embodies faith and duty, his religious worldview shattered by the occult truths he must confront. Dashwood is the embodiment of grimy, capitalist exploitation of the occult. Jan Van Ruthberg is the ambiguous shamanic figure, operating in moral grey areas. Each represents a different response to the hidden darkness of Hardland, and their interactions with Georik create a pressure cooker of social and ethical tension.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Point-and-Click of Despair

As a visual novel, Animamundi’s gameplay is fundamentally about navigation and choice. The player experiences the story from a first-person, fixed “flip-screen” perspective, a somewhat archaic presentation even for its time that emphasizes static, carefully composed scenes over cinematic flair. Interaction is conducted via a point-and-select interface.

Core Loop & Time Pressure: The gameplay revolves around a relationship between exploration, dialogue choices, and item collection within a strict time limit. The narrative progresses in days. Each day, Georik must accomplish specific objectives—research at the library, meetings with contacts, procurements from the black market—all while managing his public schedule to avoid suspicion. The player clicks on screen hotspots to move between locations (his home, the city streets, the Golden Goose shop, etc.). At each location, a menu of possible actions appears (Talk, Examine, Use Item, etc.).

The time limit is the primary source of tension. Failing to complete key actions before the day ends results in a bad ending, often a grisly failure where Lilith is permanently lost or Georik is destroyed. This creates a persistent, low-grade anxiety that complements the gothic horror tone. It is less about action and more about precise management of a tragic itinerary.

Progression & Endings: “Progression” is measured in items collected (specific alchemical ingredients, black market organs, magical tools) and relationships built through dialogue choices (persuading, threatening, or pleading with characters). The game features multiple endings, heavily dependent on:

1. Acquisition of Key Items: Certain plot-critical components must be obtained in the correct order.

2. Dialogue Choices: Responses shape Georik’s relationships, opening or closing paths. Choices must often align with his desperate, morally compromised mindset.

3. Sequence-Sensitive Events: A notorious flaw in some early North American releases, as noted in the source material, was a text error triggered by clicking events in a specific order. This could soft-lock the game or make a true ending inaccessible, a critical design flaw that severely impacted the player’s ability to achieve the “correct” conclusion.

Innovation & Flaws: The innovative (for its sub-genre) element was the integration of resource management and scheduling into a visual novel framework. It felt more like managing a doomed operation than simply reading. However, the flaws were significant. The interface could be clunky. The time pressure, while atmospheric, could feel arbitrary and punitive without clear feedback. The infamous bug in some releases was a catastrophic failure demanding patches. The game essentially required a walkthrough to navigate its logic flawlessly, undermining the sense of organic discovery. The “game” is a puzzle-box of tragic cause-and-effect, but one with poorly labeled levers.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Gothic Anime Tableau

Setting & Atmosphere: Hardland is a classic European fantasy kingdom, but one steeped in gothic horror. The contrast is key: the grandiose, almost fairy-tale architecture of the capital and aristocracy versus the squalor, superstition, and occult underpinnings festering in the shadows. The world feels lived-in but rotten, a place where science (in the form of St. Germant’s inventions) and superstition (the witch-hunting mob) coexist uneasily, with a deeper, older darkness—the art of alchemy—linking them both. The atmosphere is one of claustrophobic dread; Georik is trapped in a society that condemned his sister and now demands he participate in its darkest secrets to fix it.

Visual Direction: The art is pure anime/manga aesthetic, but applied to a gothic framework. Character designs, particularly Lilith’s Gothic Lolita outfits and the sharp, aristocratic features of Georik and St. Germant, are elegant and distinctive. The static backgrounds are richly painted, capturing the opulence of manors and the grit of back-alley markets. However, the visual presentation is hampered by the fixed/flip-screen format and 640×480 resolution. Sprites are not animated, and while CGs (computer graphics) are used for key dramatic moments, they are static images with no effects. This gives the game a dated, “early 2000s PC visual novel” look that prioritizes illustration over cinematic motion. The horror is conveyed through static imagery—the shocking CG of Lilith’s beheaded body on the pyre, the grotesque anatomical diagrams—relying on the player’s imagination to fill the gaps, a classic effective technique in the genre.

Sound Design & Music: This is universally cited as Animamundi‘s greatest strength. The game features a full symphonic and choral score, a lavish production for such a niche title. The music is profoundly effective: sweeping, mournful themes for Georik’s grief; ominous, dissonant strings for scenes of investigation and dread; and chilling, ethereal choir pieces for moments of supernatural horror or Lilith’s appearances. It elevates the entire experience, providing an emotional and atmospheric through-line that the static visuals can only suggest. The voice acting is also praised as “superb,” with a cast of notable Japanese seiyuu (Yui Horie as Lilith, Ryotaro Okiayu as Georik, Hiroki Yasumoto as Mephistopheles) delivering performances that imbue the text with palpable emotion—Lilith’s fragile innocence, Georik’s crumbling resolve, Mephistopheles’ serpentine charm. For an English-speaking audience, the Hirameki dub was noted as professionally done, a rarity for such titles at the time.

Reception & Legacy: Censorship, Bugs, and a Cult Following

Launch Reception: Animamundi attained almost zero mainstream coverage. Its distribution was hyper-limited (DVD-ROMs for PC/Mac sold through niche online retailers and anime conventions). It existed almost entirely in the ecosystem of dedicated visual novel fans and “AnimePlay” collectors.

Within that ecosystem, reception was highly polarized.

* The Praises: Reviews on sites like GrrlGamer.com and GamerGirlsUnite.com highlighted exactly what the game excelled at: its “beautiful artwork, great musical score… superb voice acting,” and its “elaborate story line and dialogue.” The English localization was, for the most part, commended for its professionalism. The sheer audacity of its gothic horror premise was a major draw for those seeking something darker and more literary than the typical dating sim or slice-of-life story.

* The Controversies: Two major issues defined its Western legacy:

1. Censorship & “Taming”: The North American release was infamous for editing or omitting in-game graphics featuring gore or “soft yaoi” (male homoerotic content). This directly impacted the integrity of the gothic horror and the complex, often charged, relationships between Georik and other male characters (like the devoted St. Germant or the sinister Glening). The game’s ESRB “M” (Mature) rating came with a rare and controversial “Sexual Violence” descriptor, a first for the ESRB, highlighting the disturbing content. For purists and fans of the original vision, the censored version was a crippled product. Hirameki’s response—releasing limited copies of the Japanese official art book—was a small, belated gesture that did little to fix the core game.

2. Technical Deficiencies: The “text error” bug that could be triggered by a specific sequence of events was a game-breaking flaw in early printings, requiring players to seek out and apply patches (“A Quiet Corrosion” and “Outbreak of War” patches, as noted on VNDB). This shoddy quality control severely damaged its reputation for reliability.

Evolving Legacy: Today, Animamundi is remembered as a cult classic and a cautionary tale.

* Influence: It had no direct, measurable influence on major Western studios. Its legacy is more cultural within the visual novel/otome gaming community. It stands as an early, bold attempt to bring a serious, dark gothic horror VN to the West. Its struggles with censorship predated wider conversations about “localization fidelity” that would explode years later with games like Muv-Luv or Clannad.

* Preservation & Restoration: The existence of fan patches to restore the censored content is a key part of its history. This mirrors a broader trend of fan-driven preservation for visually and thematically intense Japanese media. Its availability on GOG’s “Dreamlist” (a user-voted wishlist for potential releases) indicates a persistent, if small, desire for a proper, uncensored re-release.

* Historical Footnote: Its distinction as the first ESRB-rated game with a “Sexual Violence” descriptor secures it a footnote in regulatory history, a grim milestone reflecting the contentious nature of its content.

Conclusion: The Tormented Value of a Flawed Gem

Animamundi: Dark Alchemist is not a great video game by conventional metrics. Its interface is dated, its technical execution was plagued by bugs, and its Western release was a compromised, censored shadow of the original vision. Yet, to dismiss it solely on these grounds is to miss its profound, disturbing power.

Its value lies in its uncompromising thematic core. The story of Georik and Lilith is a masterclass in gothic narrative mechanics: the collision of love and monstrosity, the price of forbidden knowledge, the societal roots of individual tragedy. Supported by a phenomenal voice cast and a haunting symphonic score, the emotional and psychological weight of its scenes—Lilith’s whispered pleas from her severed head, Georik’s silent resolve as he commits atrocities for her—transcend its simple presentation.

In the canon of video game history, Animamundi is a specialist’s artifact. It is a primary source for understanding the challenges of bringing Japanese visual novels—particularly those dealing with extreme psychological and corporeal horror—to Western audiences in the mid-2000s. It exemplifies the culture clash: between artistic intent and regional sensibilities, between niche distribution and mainstream visibility, between a story’s darkness and a publisher’s fear.

For the historian, it is a poignant case study. For the player willing to seek out a restored version, it is a harrowing, unforgettable descent into a beautifully rendered hell. Its legacy is not one of sales or awards, but of a raw, gothic nerve exposed—a nerve that continues to pulse with discomfort and fascination over two decades later. It remains, ultimately, the story of a beheading that the industry, in its attempt to “tame” it, could never quite sever.