- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company, Anino Entertainment, Nordic Softsales AB, Prelusion Games Inc.

- Developer: Anino Entertainment

- Genre: Role-playing

- Perspective: Isometric

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Quest-based, Real-time combat, Skill system, Weapon variety

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 47/100

Description

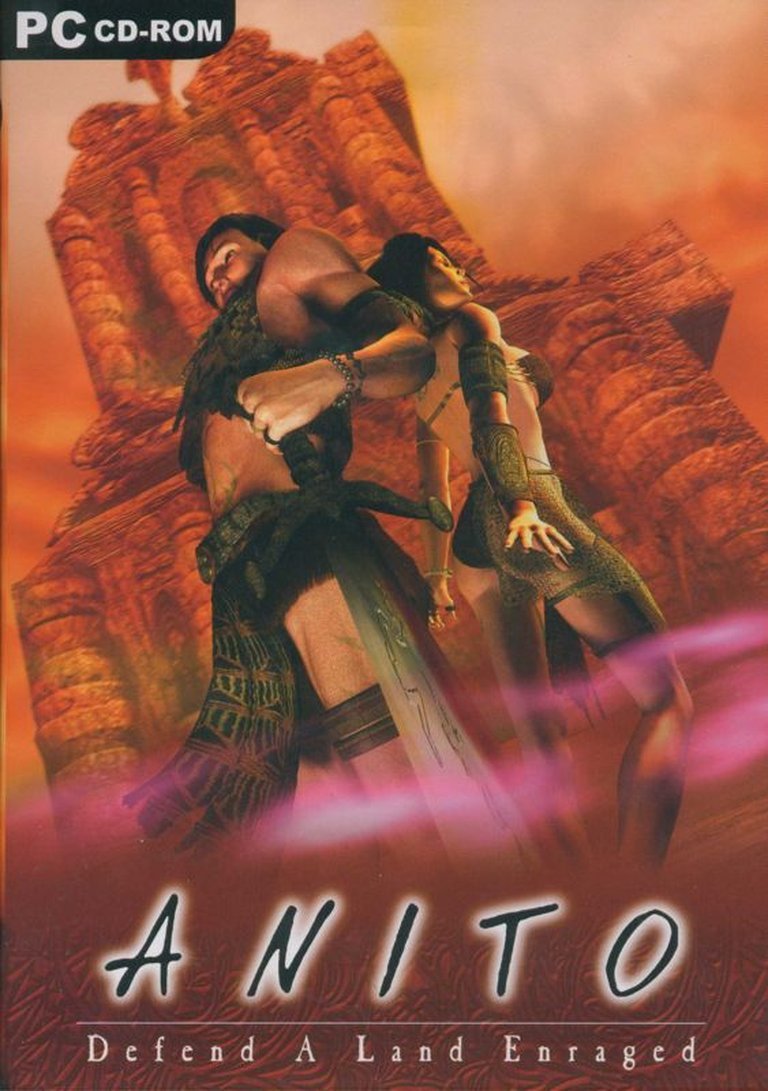

Anito: Defend a Land Enraged is a role-playing game set in the fictional 16th century Asian realm of Maroka. Players choose from two characters to explore rich tribal and colonial settlements, undertake quests across five towns, and engage in real-time combat with weapons inspired by Asian and European styles, while mastering a Chakra-based skill system and facing enemies drawn from Asian folklore like the tikbalang.

Gameplay Videos

Anito: Defend a Land Enraged Free Download

Anito: Defend a Land Enraged Patches & Updates

Anito: Defend a Land Enraged Reviews & Reception

ign.com (47/100): But it’s not all bad. Some elements of Anito show a lot of care went into the game.

Anito: Defend a Land Enraged: A Landmark of Philippine Gaming and Folklore, Wrought in Ambition

Introduction: The First Stone in a New River

In the early 2000s, the global video game landscape was dominated by colossal studios and multi-million dollar budgets. Into this arena stepped a small team from Manila, Philippines, with a dream and a profound sense of cultural purpose. Anito: Defend a Land Enraged (2003) is not merely a game; it is a statement, a foundational artifact, and a testament to the power of localized storytelling in a then-globalizing medium. As the first commercially released PC game conceived, developed, and produced entirely by Filipinos, its legacy is secured before one even evaluates its mechanics. Yet, to dismiss it as a mere historical curiosity would be a profound error. This review will argue that Anito is a fascinating, deeply flawed, yet fiercely ambitious hybrid—part folktale, part action-RPG, part adventure game—whose unwavering commitment to its native mythology and narrative depth coalesces with notoriously uneven execution to create a singular experience that remains pivotal in understanding the history of Southeast Asian game development. It is a game that demands to be analyzed not in isolation, but as a cultural touchstone and a case study in indie development under extreme constraints.

Development History & Context: Forging a New Path

Anito was developed by Anino Entertainment, a studio founded by Niel Dagondon, Michael Rivero, Gabriel Dizon, and others. The project’s genesis in October 2001 and its two-year development cycle speak to a monumental effort for a team that, based on credits and contemporary indie averages, likely fluctuated between a core of 2-5 people and a larger collaborative network of 24 credited developers and 7 “thanks.” The financial context is stark: the team operated on a shoestring budget, a reality underscored by their simultaneous provision of 3D graphics and animation services for other industries to fund the venture. Their chosen arena was the isometric action-RPG, a genre then dominated by titans like Diablo II, Baldur’s Gate II, and Divine Divinity. The technological constraints were significant; the game uses a hybrid engine blending 2D pre-rendered backgrounds with 3D character models converted to sprites—a common mid-tier technique of the era to manage performance and asset creation, but one that would later contribute to visual criticisms.

The gaming landscape of 2003 was one of burgeoning indie scenes, primarily centered in the West and Japan. The Philippines had no established game development industry. Anito’s very existence was an act of defiance and cultural assertion. It was not just a game; it was the “first stone” in what its creators hoped would be a new river of Philippine interactive storytelling. This context is essential: judging Anito against a BioWare or Blizzard title is an apples-to-oranges exercise. It must be judged as a pioneering work from a region with zero local infrastructure, talent pipeline, or historical precedent.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Weaving Myth with Colonial Angst

The narrative of Anito is its paramount strength and its most polished element. Set on the fictional 16th-century island of Maroka, the plot masterfully blends a historical “Age of Conquest” framework with a deeply personal family drama and a rich tapestry of Filipino pre-colonial mythology and folklore.

The inciting incident is the mysterious disappearance of Datu Maktan, the peacekeeping leader of the Mangatiwala tribe. His children, Agila (the ranger) and Maya (the spellcaster), are the dual protagonists. The player’s choice between them is not a superficial class pick; it fundamentally alters the narrative path, providing two distinct yet complementary perspectives on the unfolding crisis. This branching structure, while limited in scope, was ambitious for a project of this scale.

Thematically, the plot is a three-way tension:

1. Internal Tribal Conflict: Political strife and ancient rivalries among Maroka’s indigenous peoples.

2. External Colonial Invasion: The slow, relentless encroachment of “armored invaders from a faraway place”—a clear allegory for Spanish colonization, though never named explicitly—threatening to subsume the land under a foreign monarch’s rule.

3. Mythological Resurgence: The awakening of ancient anito (spirits/deities) and creatures from folklore, such as the fearsome tikbalang (a horse-headed demon), which are not mere monsters but manifestations of a spiritual world destabilized by the colonial threat and the Datu’s absence.

The writing, as noted in several reviews, is dense and committed. NPCs are loquacious, history is delivered via in-game books and dialogues, and the central quest is less about “fetch X items” and more about political mediation, spiritual understanding, and uncovering a conspiracy tied to one’s own heritage. Maya’s arc, in particular, is praised for echoing the archetypal “Aragorn journey”—a search for identity and destiny through service to a land in peril. The story treats its source material with reverence, embedding concepts like chakra (drawn from Hindu-Buddhist influences in the Philippines) as a core magical system. For many players, particularly in the Filipino diaspora, this representation was electrifying—a digital space where their cultural narratives were the default, not a exoticized sidebar.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Cracks in the Foundation

Here lies the game’s most contentious terrain. Anito‘s fundamental identity crisis is a hybrid adventure/RPG design, but it leans dangerously close to being a “talking simulator” with intermittent combat.

-

Core Loop & Progression: The “task list” or journal system is robust, tracking numerous quests. Progression is tied to a Chakra-based skill system. Seven colored Chakras represent schools of magic/ability (e.g., Red for combat, Blue for spirit magic). Skills are acquired through quest completion, finding items, and awakening new Chakras. “Skill Up” points are earned to enhance these abilities. This system is conceptually rich and thematically integrated but is criticized for being passive; players have little granular control over point allocation, and spell acquisition feels scripted rather than earned through conventional experience points.

-

Combat: Real-time and clunky. Players click to attack, with on-screen text indicating hits/misses—a system detractors found immersion-breaking. The variety of Asian and European-inspired weapons (swords, shields, bows) exists, but fluid combos or tactical depth are minimal. Enemy variety (from human bandits to folklore beasts) is a plus, but combat frequency is low. Many reviewers, including those from Game Tunnel and Worth Playing, noted hours of gameplay passing with only a handful of fights, making the “RPG” label feel misleading. The challenge is often in attrition (managing health/chakra) rather than tactical mastery.

-

Exploration & Interaction: The world of Maroka is presented in an isometric view with 2D backgrounds. Exploration is hampered by opaque pathfinding and spatial disorientation. The 2D art, while sometimes “breath-taking” per Game Tunnel, often lacks clear depth cues, leading to getting “stuck” on geometry. Loading screens between areas are frequent and break momentum. Inventory management includes a crafting-like system where items (like wild boar meat) must be used on environmental objects (a stove) to create new items (pork chop). This interactive world-building is clever but inconsistently implemented and often feels like busywork.

-

UI & Systems: The user interface is functional but dated. The day/night cycle affects NPC availability and vendor access, a nice touch that encourages planning. However, the reliance on resting to restore mana/chakra, which advances the clock, can make progress feel slow and artificially padded. The lack of a fast-travel system (compared to the beloved portals in Divine Divinity, as noted by the Worth Playing reviewer) makes traversal a significant time sink.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Symphony of Folklore, Marred by Technical Debt

Anito’s soul resides in its aesthetics, particularly its audio.

-

Art Direction & Visuals: The game’s visual identity is a blend of stylized 16th-century Asian tropics and colonial European outposts. The character models, animated from 3D to 2D sprites, show a clear technical compromise of the era. Animations are simple, and the isometric perspective sometimes obscures pathways. The environments, when they work, evoke a lush, humid, mythic Philippines. The “tikbalang” and other creature designs are direct, respectful adaptations of folklore. However, as PC Zone (47%) cruelly stated, the “dated presentation” is a “constant reminder” of its small-scale production. It lacks the cohesive, painterly polish of Planescape: Torment or the atmospheric density of Fallout 2. It is a game of striking individual assets occasionally unified by a strong artistic vision.

-

Sound Design & Music: This is Anito‘s undisputed crown jewel and the source of its Independent Games Festival 2004 Innovation in Audio award. Composer Don Billones created a soundtrack that is not merely background but a narrative engine. It weaves traditional Filipino instruments (kulintang, gangsa) with orchestral and ambient textures, creating a soundscape that is at once ethnographic and epic. The main theme is “memorable,” searing itself into the player’s mind as one review put it. Sound effects for creatures like the tikbalang are authentically creepy and rooted in local myth. The audio design does the heavy lifting of making Maroka feel ancient, spiritual, and alive—a feat that outshines the visual limitations. It is the primary vehicle for the game’s emotional and cultural resonance.

Reception & Legacy: A Fractured Reputation, A Foundational Success

Anito’s launch reception was profoundly mixed, mirroring its design dichotomy.

-

Critical Scores: The range is extreme: Game Tunnel (90%), Game Shark (75%), Worth Playing (70%), Withingames (60%), and PC Zone (47%). Metacritic and GameRankings sit at ~63/55%. The divide is clear: critics who prioritized narrative, cultural significance, and contextual indie achievement (the first three) praised it highly. Those who evaluated it strictly against mainstream RPG benchmarks on technical execution, UI, and combat frequency panned it. PC Zone‘s verdict that it is merely “an interesting novelty diversion” for veterans represents one pole; Game Tunnel‘s claim that it is “amazing” for $20 and “delight[s] any gamer” represents the other.

-

Commercial & Cultural Impact: On commercial terms, it was a modest success for a niche Filipino product, sold directly from Anino’s website and through limited international publishers (Prelusion, Nordic Softsales, 1C). Its true victory was cultural. It proved a Filipino development studio could produce, publish, and distribute a full PC RPG to the global market. It became a symbol of national pride and sparked essential conversations about developing a local game industry. It directly inspired a new generation of Filipino developers and is frequently cited in academic papers on Southeast Asian game studies. The existence of mobile prequels (Anito: Tersiago’s Wrath, Anito: Call of the Land) and its continued presence on abandonware and GOG wishlists signify a lasting, if cult, appeal.

-

Influence: Its direct influence on global AAA design is negligible. Its influence is indirect and symbolic. It paved the way for a Philippine indie scene that would later produce titles like Crossfire (by Smilegate, though Korean-developed) and a host of mobile games. More importantly, it joined the global vanguard of “regional mythos” games (like Kingdoms of Amalur: Reckoning‘s Celtic inspiration or The Witcher‘s Slavic base) years before that trend became mainstream. It demonstrated that non-Western, non-Japanese mythologies could be the core of a game’s identity, not a costume.

Conclusion: The Land is Enraged, and So is Its Legacy

Anito: Defend a Land Enraged is an irrepressible, contradictory masterpiece of context. As a pure RPG/adventure, it stumbles: its combat is perfunctory, its interface clunky, its visuals a product of harsh compromise, and its pacing deliberately slow. It asks the player to engage with its world as a storyteller first and a warrior second—a pitch that worked for some and alienated others.

But as a cultural artifact, it is unimpeachable. It is the foundational text of Philippine video game history. Its unwavering commitment to presenting a Filipino worldview, where colonial history is the backdrop and anito are the spiritual reality, was revolutionary in 2003. The sound design alone elevates it to a must-study piece for understanding how audio can anchor a game in a specific cultural milieu.

Its MobyScore of 6.7 and Metacritic of 63 are numbers that fail to capture its duality. For the historian, it is a 9/10—a landmark achievement against all odds. For the 2003 RPG purist seeking the next Diablo, it is a 4/10—a frustrating, dated curiosity.

Ultimately, Anito is a brave, beautiful, and deeply flawed game that deserves to be played not for its perfection, but for its audacity. It is the digital equivalent of a hand-carved anito statue: rough around the edges, imbued with immense spiritual and cultural weight, and standing as an undeniable testament to a people’s will to see their stories, their monsters, and their heroes rendered in pixels and code. To defend Anito is to defend the right of all cultures to build their own digital mythologies, no matter how enraged the technical constraints may make the process. Its legacy is not in how many copies it sold, but in the door it kicked open for those who followed.