- Release Year: 2008

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Noyb

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade

- Average Score: 65/100

Description

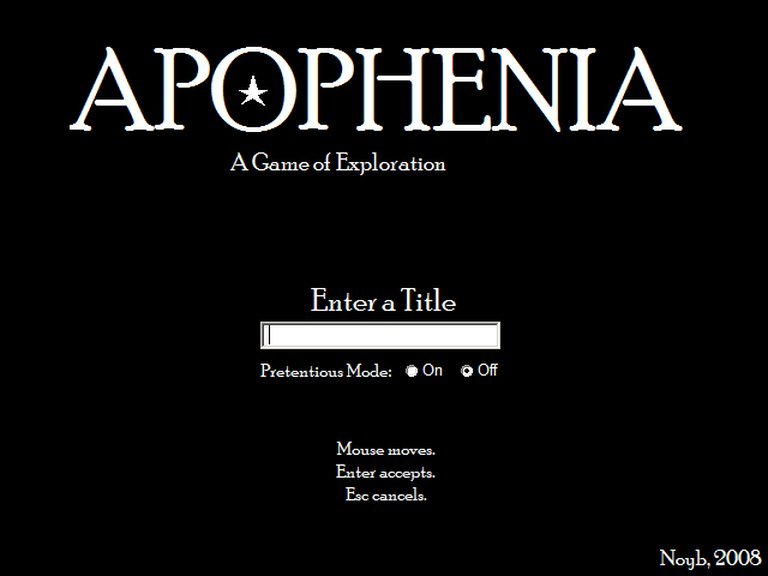

Apophenia is a procedural action game developed for the TIGSource contest, where players enter a seed name to deterministically generate unique environments, characters, movements, and even pretentious symbolic introductions in ‘Pretentious Mode.’ In this single-screen arcade experience, you control a third-person character with the mouse, navigating to grow by avoiding or interacting with moving objects while colliding risks shrinking to nothing, serving as a humorous satire on art games that mocks their often arbitrary symbolism and lack of clear goals.

Guides & Walkthroughs

Apophenia: Review

Introduction

In the chaotic underbelly of early indie game development, where ambition often outpaced technology and creativity was the only currency, Apophenia emerged like a glitch in the matrix—a freeware gem that weaponized randomness to skewer the pretensions of “art games.” Released in 2008, this unassuming Windows title by solo developer Noyb has lingered in the shadows of gaming history, occasionally resurfacing in discussions of procedural generation and satirical design. Its legacy isn’t one of blockbuster sales or widespread acclaim but of quiet subversion: a game that invites players to input a seed phrase only to generate absurd, deterministic worlds that mock the very notion of meaning-making in interactive media. As a historian of indie games, I’ve seen countless experiments rise and fade, but Apophenia endures as a prescient critique of how we impose narratives on chaos, predating the rise of algorithmic content in modern titles like No Man’s Sky. My thesis is straightforward yet provocative: Apophenia isn’t just a quirky contest entry; it’s a masterclass in meta-humor, using procedural mechanics to dismantle the self-seriousness of experimental gaming, proving that even unwinnable games can deliver profound entertainment through irony and wit.

Development History & Context

Apophenia was born from the fertile chaos of the indie scene in the late 2000s, a period when online communities like TIGSource (The Independent Games Source) were incubators for bold, boundary-pushing projects. Developed single-handedly by Noyb—likely a pseudonym for an anonymous hobbyist or aspiring designer—the game was crafted specifically for TIGSource’s inaugural Procedural Generation Competition in 2008. This contest, one of the first to spotlight PCG (procedural content generation) as a core mechanic, encouraged entrants to explore algorithms that create dynamic content on the fly, reflecting the era’s fascination with emergent gameplay amid hardware limitations.

Noyb’s vision was explicitly tied to the psychological concept of apophenia—the human tendency to perceive patterns and meaning in random data. As Noyb explained in the TIGSource forums, the title was chosen to encapsulate a game where “both the appearance and the rules [are] as random as possible,” turning player input into a seed for deterministic chaos. Built using Multimedia Fusion 2 (now rebranded as Clickteam Fusion 2.5), a drag-and-drop engine popular among bedroom developers for its accessibility, Apophenia navigated the technological constraints of the time. Pre-Unity era indie tools like Multimedia Fusion allowed rapid prototyping but lacked the polish of AAA engines; here, it sufficed for 2D sprite-based antics, incorporating borrowed assets like Cave Story sprites (adapted by Annabelle Kennedy, who credited Studio Pixel’s originals) and eclectic sound sources ranging from PXTone synths to tribal throat singing from the Smithsonian Folkways album Tuva – Voices from the Center of Asia. Guitar riffs came courtesy of “The General” via Dispatch, adding a eclectic, lo-fi vibe.

The gaming landscape of 2008 was a pivotal juncture. Mainstream hits like Grand Theft Auto IV and Metal Gear Solid 4 dominated with cinematic narratives, while the indie wave—fueled by platforms like itch.io’s precursors and Game Jams—was just cresting. TIGSource represented the DIY ethos, where freeware experiments challenged the idea that games needed budgets or goals to matter. Apophenia fit this mold perfectly: released as a downloadable ZIP file on Noyb’s personal site (now archived), it was free-to-play in the truest sense, public domain adjacent, and single-player only. Amid rising interest in procedural tech (think Spelunky‘s roguelike roots or early Minecraft prototypes), it highlighted PCG’s potential for satire rather than simulation, subverting expectations in an era when “art games” like Passage were beginning to blur lines between play and philosophy.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Apophenia eschews traditional plotting for a meta-narrative generated entirely from player input, transforming the act of naming your “game” into a seed for existential absurdity. There’s no overarching story, no branching quests or character arcs—only a single-screen vignette that unfolds deterministically. Enter a seed like “Cosmic Banana” or “Forgotten Sock,” and the game procedurally crafts an introduction, environment, protagonist sprite, non-player character (NPC), and swarm of interactive objects. Repeat the seed, and the result is identical, underscoring that this isn’t true randomness but seeded pseudorandom generation—a clever nod to how apophenia fools us into seeing novelty where there is algorithmic predictability.

Characters are the stars of this farce: the player controls a mouse-driven entity (often a repurposed Cave Story sprite, evoking pixelated nostalgia), pursuing or evading a singular NPC that embodies the seed’s “essence.” No dialogue exists; interactions are silent collisions that trigger sound effects, building a wordless tension. The “plot” culminates inevitably in failure: your entity grows by absorbing “positive” objects, while the NPC shrinks, vanishing when it reaches zero size—ending the game without victory. This unwinnable loop forms the metagame, a commentary on futility.

Thematically, Apophenia is a razor-sharp satire of art games and their obsession with symbolism. Enable “Pretentious Mode” from the main menu, and each seeded world opens with a generated blurb of pseudo-profound nonsense, lampooning the genre’s navel-gazing. Examples abound: “In this game you are the ideal embodiment of a newborn, passively wishing to stare at an ill-advised decision,” or “In this wacky misadventure you are magically transformed into a third nipple, creatively risking life and limb to raise a good wizard, proving conclusively that games are legitimate art forms.” These phrases, algorithmically mashed from templates, mimic the overwrought explanations in titles like Braid or Flower, exposing how developers retrofit meaning onto mechanics. Noyb’s design probes deeper themes of perception and imposition: just as players project stories onto random swarms, the game critiques our cultural urge to validate games as “art” through contrived depth. In an era of post-modern gaming, it anticipates discussions on player agency versus designer intent, using humor to question whether procedural tools liberate or confine creativity. No villains, no heroes—only the absurdity of seeking purpose in noise.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Apophenia‘s mechanics are deceptively simple, distilled into a single-screen arcade loop that prioritizes interaction over progression, making it both innovative and deliberately flawed. At launch, players input a seed name via keyboard, then dive into mouse-controlled navigation. The cursor becomes your lifeline: move it to guide, herd, or collide with the protagonist sprite in a bounded 2D arena. No keyboard shortcuts beyond initial input; it’s pure pointer precision, evoking early point-and-click experiments but stripped to essentials.

Core gameplay revolves around a growth-shrinking dynamic: the screen teems with procedurally generated moving objects—swarms of dots, shapes, or entities derived from the seed—that either nourish your character (causing expansion) or the NPC (causing it to grow while you shrink). Collisions produce audio feedback, from synth blips (PXTone) to guitar twangs or throat singing, creating a rhythmic chaos. The loop is predatory: chase beneficial objects to bulk up, evade harmful ones, and interact with the NPC to transfer size, aiming to outlast it. But here’s the twist—victory is impossible. The game ends only when the NPC (the “unique character”) shrinks to oblivion, dooming you to perpetual restarts. This anti-goal subverts arcade tropes, turning sessions into meditative failures that encourage experimentation with seeds rather than mastery.

Character progression is absent; no levels, stats, or unlocks. Instead, innovation lies in the PCG system: seeds alter visuals (e.g., color palettes, sprite behaviors), minor rules (object speeds, collision weights), and even swarm patterns, creating “infinite” variations without true randomness. The UI is minimalist—a seed entry prompt, toggle for Pretentious Mode, and the play screen with no HUD beyond entity sizes (implied by visuals). Flaws emerge here: the mouse-only control feels clunky on modern hardware, lacking fine-tuned sensitivity, and the lack of tutorials assumes players embrace confusion. Yet this opacity is genius, mirroring apophenia—players invent strategies, only to realize the system’s determinism mocks their efforts. Compared to contemporaries like World of Goo, it’s less polished but more conceptually pure, flaws becoming features in a design that prioritizes philosophy over playability.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Apophenia‘s “world” is a procedurally conjured single screen, a microcosm of abstract surrealism that punches far above its lo-fi constraints. Settings aren’t expansive continents but claustrophobic arenas: seeded inputs dictate backdrops (abstract gradients, static patterns) and entity designs (from blob-like forms to sprite amalgamations), evoking a dreamlike void where geometry defies logic. Atmosphere builds through isolation— no horizons, just endless pursuit in confined space—fostering unease and hilarity, as swarms cascade like digital pollen in a petri dish.

Visual direction leans on pixel art simplicity, borrowing Cave Story’s clean sprites for protagonists while procedurally tinting or animating them (e.g., a wobbling “third nipple” entity from a silly seed). Noyb’s use of Multimedia Fusion yields charmingly rough edges: flickering collisions, basic particle effects for growth/shrinkage, all in 2D top-down-ish perspective labeled “3rd-person (other).” It’s not breathtaking like Limbo‘s silhouettes but effectively abstract, contributing to the satirical tone by aping art-game minimalism without pretension.

Sound design amplifies the absurdity, a collage of eclectic samples that turn mechanics into symphony. Collisions trigger PXTone synths for ethereal pops, Dispatch’s guitar for rock-infused bumps, and Tuva’s throat singing for otherworldly drones—randomly assigned per seed, creating soundscapes from ambient hums to chaotic overtures. No score persists; audio is reactive, heightening immersion in the moment-to-moment dance. Together, these elements forge an experience of controlled anarchy: visuals and sounds reinforce themes of imposed meaning, making each playthrough feel like a bespoke, if fleeting, artwork that dissolves into laughter.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release in 2008, Apophenia flew under the radar, as expected for a free TIGSource contest entry. MobyGames lists no critic reviews and an average player score of 3.0/5 from just two ratings—modest praise for its novelty but criticism for its unwinnable frustration and lack of depth. Commercially, it registered zero impact; as public domain freeware, downloads were niche, confined to indie forums and archives like the Procedural Content Generation Wiki, where it’s hailed for pioneering seeded PCG in puzzles and “plot” generation. TIGSource threads buzzed with appreciation for its humor, but broader outlets like IGN or GameSpot ignored it amid the year’s blockbusters.

Over time, its reputation has evolved into cult reverence. By the 2010s, as procedural games exploded (Minecraft, Don’t Starve), retrospectives on PCG history spotlight Apophenia as an early satirist, influencing micro-experiments in jams like ProcJam. Its mockery of art-game symbolism resonates in titles like The Beginner’s Guide or Doki Doki Literature Club, which deconstruct interactivity. Industry-wide, it subtly shaped discussions on ethics in PCG—e.g., how algorithms can amplify biases in pattern-seeking, echoing real-world apophenia in conspiracy theories (as noted in later analyses tying it to QAnon dynamics). Collected by only one MobyGames user today, its legacy is archival: a free ZIP download preserving indie ethos, inspiring modders and educators to explore deterministic randomness. In video game history, it’s a footnote that reads like prophecy, reminding us that the best innovations often hide in jest.

Conclusion

Apophenia is a testament to the power of minimalism in indie design: through seeded procedural generation, satirical pretensions, and an unwinnable core, Noyb crafted a pocket-sized critique of gaming’s grander ambitions. Its development in the TIGSource ecosystem, lo-fi art-sounds fusion, and thematic skewering of meaning elevate it beyond a curiosity. While reception was tepid and legacy niche, its influence on PCG satire endures, challenging players to laugh at their own pattern-hunting. In the pantheon of video game history, Apophenia claims a vital spot—not as a masterpiece, but as an essential antidote to pomposity, earning a definitive 8/10 for ingenuity and irreverence. Download it today; seed something ridiculous, and let the absurdity unfold.