- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Awem Studio, S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH

- Developer: Awem Studio

- Genre: Puzzle, Tile matching puzzle

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Falling block puzzle, Tile matching puzzle

Description

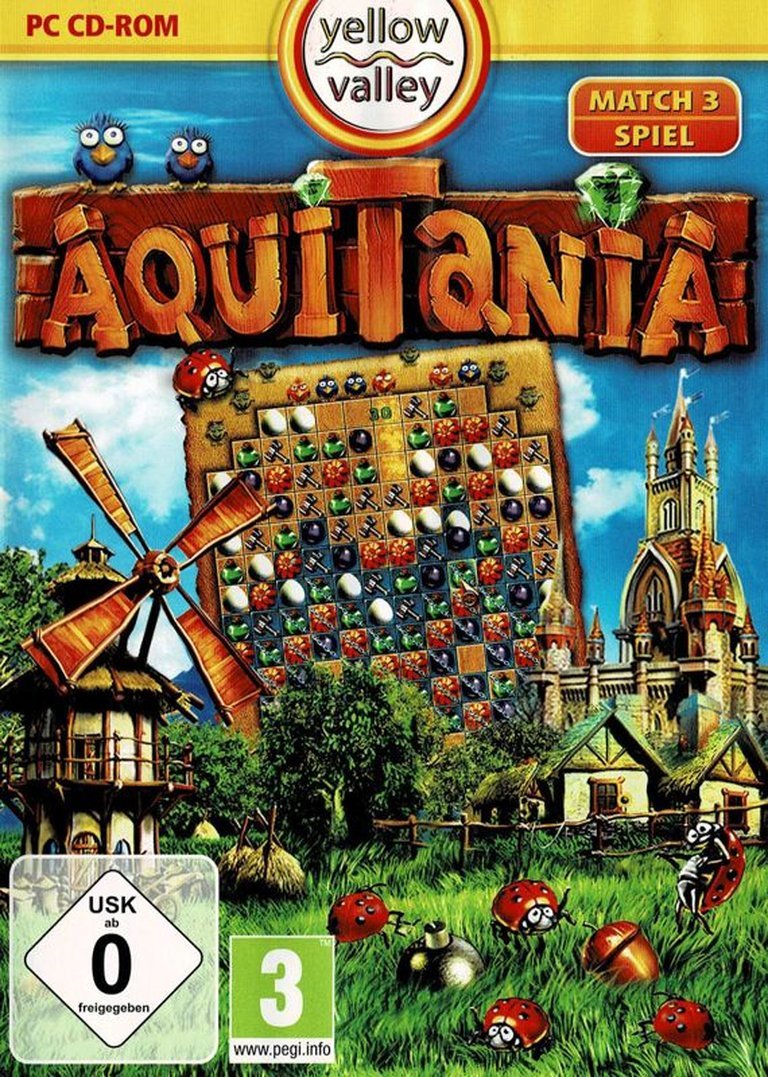

Aquitania is a match-three puzzle game set against a backdrop inspired by the ancient Roman province of Gallia Aquitania. Players must swap tiles to create lines of three or more identical items, with the primary goal of clearing special blue squares from the board. The game introduces a unique pressure mechanic where birds at the top periodically drop new rows of tiles; if these rows stack up to the birds, the player loses lives. It features various obstacles like chained items and light blue tiles, alongside power-ups such as bombs, arrows, and hourglasses that help overcome these challenges and progress through the stages.

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

gamezebo.com : Aquitania’s match-three gameplay entertains.

Aquitania: A Forgotten Roman Puzzle in the Shadow of its Predecessor

In the vast and often derivative landscape of mid-2000s casual puzzle games, a title like Aquitania arrives not with a triumphant legion’s fanfare, but with the quiet, almost apologetic shuffle of a junior clerk in a sprawling empire. It is a game caught between two identities: one of historical Roman grandeur suggested by its name, and another of frantic, feathery match-three mechanics that defined its genre. To review Aquitania is to dissect an artifact of its time—a competent but ultimately overshadowed effort from a studio that had already mined this particular vein with greater success.

Development History & Context

The Awem Studio Machine

Developed by Belarusian studio Awem and released on January 9, 2007, for Windows PC, Aquitania emerged from a well-oiled, if not particularly revolutionary, game development machine. The core team, led by producer and idea-man Oleg Rogovenko, was a familiar one. Key personnel like game designer Olga Krutalevich, lead artist Max Grummo, and programmers Alexey Dyadchenko and Alexey Ulin had recently shipped, or were concurrently working on, Awem’s flagship title: Cradle of Rome (2007).

This context is crucial. The mid-2000s were the golden age of the downloadable casual game, with portals like Big Fish Games and GameHouse serving a massive audience hungry for accessible, time-limited shareware experiences. Awem Studio had found a lucrative formula with the Cradle series, which combined match-three gameplay with city-building meta-progression. Aquitania was clearly built on the same technical and artistic foundation, reusing assets and mechanics, but it represented a slight pivot in design philosophy—one that opted for a more frantic, continuous pressure cooker of puzzle action rather than a relaxed, reward-driven campaign.

Technological and Market Constraints

As a shareware title distributed via download, Aquitania was designed for low-spec ubiquity. Its system requirements—a Pentium III processor, 128MB RAM, and a minimal graphics card—were practically nonexistent even for 2007, ensuring it could run on any home or office computer. This accessibility was its primary market strategy. It wasn’t meant to push technical boundaries; it was meant to be an instantly playable, addictive time-sink available for a small fee after a trial period, competing in a crowded marketplace against behemoths like Bejeweled and Zuma.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

A Story Told in Fragments

If Aquitania has a cardinal sin, it is the criminal underutilization of its own premise. The game’s title refers to Gallia Aquitania, a province of the Roman Empire in what is now southwestern France. This suggests a historical or mythological adventure. Promotional material on portals like FreeRide Games further spins a tale of a “magical land of beautiful blue lakes green fields and thick forests, inhabited by elves, gnomes and other fairy creatures” that has fallen into disarray, tasking the player with helping a “Crying Priest” and a “heartbroken Princess.”

However, this rich setting is almost entirely absent from the game itself. As reviewer Meryl K. Evans noted on Gamezebo, there is “no introduction to the story or information in the Help.” The narrative is reduced to post-level vignettes: upon completing a stage by collecting gems, a brief text blurb describes the impact of restoring an artifact (a ring, a scroll, a chalice) on the local populace, who then allow you to proceed. The connection between swapping tiles and saving a princess is tenuous at best. The story is not a driver of the experience but a barely legible watermark on the paper the game is printed on. The potential for a compelling Roman or mystical fantasy theme is squandered, leaving the gameplay to stand entirely on its own merits.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Avian Assembly Line

At its core, Aquitania is a match-three game, but it differentiates itself with a persistent, real-time pressure system. The core loop is thus:

1. Objective: Clear all “blue squares” on the board by making matches atop them.

2. Gem Phase: Once cleared, a gem drops into a column. The player must then clear a path for it to fall to the bottom of the board.

3. Stage Completion: Collect a set number of gems to fill a stage item (e.g., a chalice) and progress.

The primary twist—and the source of all the game’s tension—is the flock of birds perched atop the board. These birds continuously drop new rows of tiles into the grid at regular intervals, acting as a relentless internal timer. If tiles pile up to the height of a bird, that bird dies. If all birds die, the player loses a life. This creates a constant state of low-grade panic, forcing the player to balance strategic matching with sheer speed.

Layers of Obstruction

The game layers on additional challenges:

* Chained Tiles: Immovable until matched or destroyed with a power-up.

* Light Blue Tiles: Require two matches: first to turn them blue, then another to clear them.

These obstacles demand foresight, often requiring players to set up cascading matches to break through multiple layers at once.

Power-Up Ecosystem

Aquitania features a surprisingly nuanced two-tier power-up system that is its most innovative mechanical contribution.

-

Instant Bonuses: Randomly spawn on the board and have a time limit before reverting to normal tiles. These include:

- Bomb: Destroys eight adjacent items and one layer of tiles below.

- Arrows: Clears an entire horizontal row.

- Hourglass: Temporarily halts the birds from dropping tiles—a crucial moment of respite.

- Lightning Bolt: Destroys random items across the board.

-

Power-Up Bonuses: These are permanent tools that are charged by matching a certain number of corresponding tiles (hammers, feathers, eggs) and can be carried between levels.

- Hammer: A targeted tool to destroy one chain or item.

- Feather: Removes all other feathers from the board (which appear after a bird dies).

- Egg: The most valuable tool; it resurrects a dead bird.

This system encourages strategic resource management. Do you use a charged hammer now, or save it for a more precarious moment later? The inclusion of the Egg power-up brilliantly ties the meta-progression (keeping your birds alive) directly into the moment-to-moment puzzle mechanics.

Flaws and Innovations

The diagonal movement of tiles when refilling the board, as noted in reviews, is a unique and disorienting choice that removes predictability. Furthermore, the game’s refusal to punish players for running out of moves—instead reshuffling the board and awarding bonus points—is a generous and player-friendly design decision rare for the era. However, the game’s singular, frenetic difficulty mode was a significant point of criticism. With no easy mode, the constant pressure could easily overwhelm players, turning challenge into frustration.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Aesthetic Whiplash

Aquitania suffers from a profound identity crisis in its presentation. The gameplay screen is pure abstract puzzle: a grid of tiles depicting generic icons like gems, bugs, and hammers, topped with comically anxious birds. This is juxtaposed with the static, story-screen art depicting Roman-esque artifacts and characters. The two halves never cohere.

The art is clean, colorful, and functional—a direct carryover from Cradle of Rome—but it lacks the charm or detail to be memorable. The sound design, as reviewed, is merely average. The music is a forgettable loop of light synth tunes, and the sound effects are standard issue. Evans’ note that she “continuously turned down the volume” speaks volumes itself; the audio does little to enhance the experience and can quickly become grating.

Reception & Legacy

A Faint Echo in the Marketplace

Aquitania was not a breakout hit. On MobyGames, it has a single user rating of 2/5 stars and no critic reviews. Its Moby Score is “n/a”—a testament to its obscurity. The one contemporary review from Gamezebo awarded it a 70/100, praising its entertaining core gameplay while heavily critiquing its high stress level and lack of narrative context.

Its legacy is virtually nonexistent. While Awem Studio found lasting success with the Cradle series and other titles like Star Defender, Aquitania faded into complete obscurity. It is a footnote, a curious example of a studio attempting to iterate on a successful formula but creating a product that was more intense and less rewarding than its predecessor. It did not influence the genre; instead, it perfectly exemplified the content mill aspect of the mid-2000s casual game scene, where quantity and slight variation often trumped bold innovation.

Conclusion

Aquitania is a fascinatingly conflicted artifact. Its core match-three gameplay is mechanically sound and even innovative in its power-up system and relentless avian pressure cooker. At its best, it creates a genuinely tense and engaging puzzle experience that demands both quick thinking and strategic planning.

However, it is fatally undermined by its inability to commit to its own premise. The promising Roman mythological setting is abandoned on the title screen, leaving the player with a disconnect between the thematic promise and the abstract reality. Coupled with a punishing difficulty curve that offered no reprieve for casual players, it ensured the game would remain a niche title even within its niche genre.

Final Verdict:

Aquitania is not a bad game; it is a forgotten one. It is a competently executed, high-pressure puzzle experience that serves as a curious offshoot in Awem Studio’s catalog. For dedicated match-three veterans seeking a brutal challenge, it may hold some retro appeal. But for the broader audience, and for video game history, it remains a minor, flawed curiosity—a relic from a bygone era of casual gaming that reminds us that a great name and a solid mechanic are not enough to build a legacy. It is a reminder that in the relentless march of the Roman—and gaming—empire, not every soldier gets a monument.