- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Publisher: Brøderbund Software, Inc., Jordan Freeman Group, LLC, Wanderful Inc.

- Developer: Living Books

- Genre: Educational, Reading, writing

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Board game, Hidden object, I-Spy, Interactive storybook, Mini-games, Word matching

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

In ‘Arthur’s Reading Race’, Arthur challenges his younger sister D.W. to read 10 words in exchange for ice cream, embarking on a lively journey through their town with his dog Pal. The game, designed in a vibrant cartoon style, offers interactive storybook pages filled with animations and mini-games like word-picture matching, a letter-based board game, an I-Spy scavenger hunt, and hidden clickable objects to enhance reading skills through playful engagement.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Arthur’s Reading Race

PC

Arthur’s Reading Race Free Download

Arthur’s Reading Race: A Monument to Edutainment’s Golden Age

Introduction

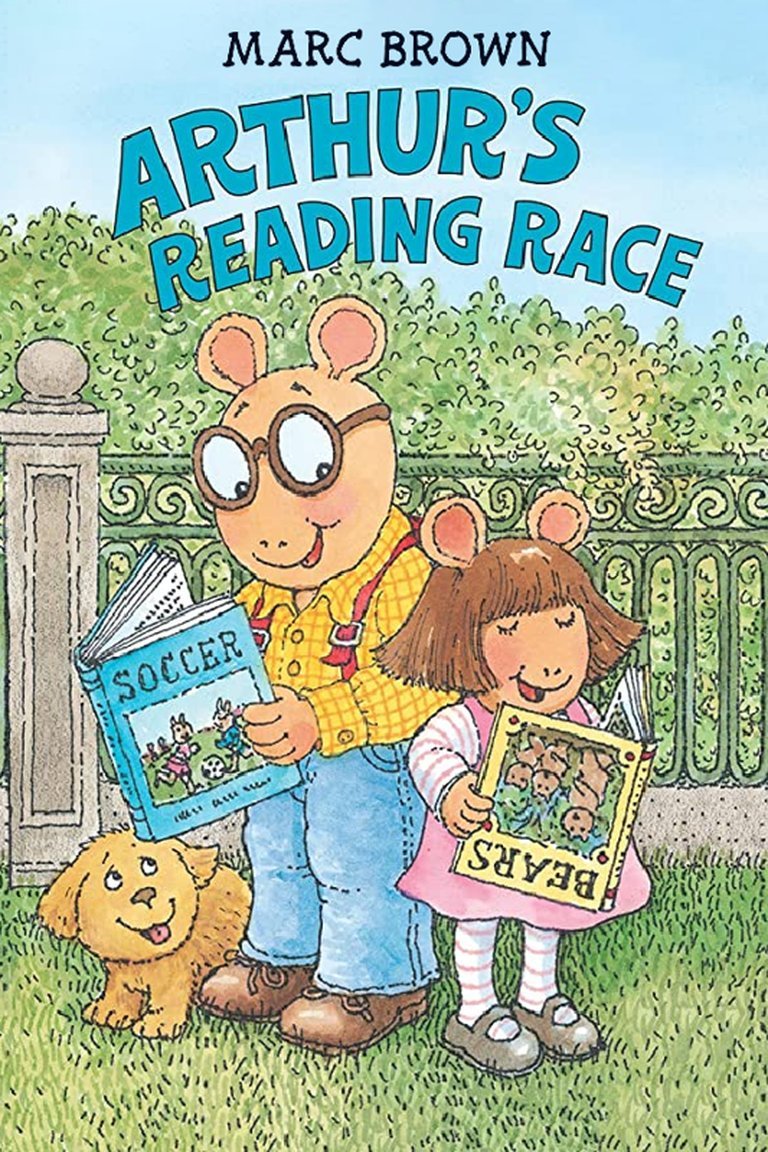

In the pantheon of edutainment, few franchises command the nostalgic reverence of Living Books, and fewer still embody their ethos as purely as Arthur’s Reading Race (1997). As the digital extension of Marc Brown’s beloved Arthur book series, this interactive storybook captured the zeitgeist of mid-90s educational software—a time when CD-ROMs promised to revolutionize learning through play. This review argues that Arthur’s Reading Race is not merely a relic of its era but a meticulously crafted bridge between literary pedagogy and digital interactivity, whose legacy persists in modern narrative-driven educational tools.

Development History & Context

Studio Vision & Technological Constraints

Developed by Living Books (a subsidiary of Brøderbund Software) under the direction of Kris Moser and Markus Schlichting, Arthur’s Reading Race emerged during the “multimedia boom” of the mid-90s. The studio had already cemented its reputation with adaptations like The Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham, leveraging the Mohawk engine to create scalable, animated experiences for early Windows and Mac systems. Technical limitations—such as 640×480 resolution and CD-ROM load times—necessitated a focus on compression efficiency and frame-by-frame animation, resulting in a product optimized for 16-bit systems like Windows 3.1.

The Edutainment Landscape

In 1997, the market brimmed with lite-edutainment titles, but few offered the narrative depth of Living Books’ catalog. Competitors like Reader Rabbit prioritized skill drills, while Arthur’s Reading Race doubled down on emergent literacy through organic interaction. As part of a broader Arthur franchise expansion that included Creative Wonders’ skill-based games (e.g., Arthur’s Math Games), Living Books’ approach diverged by treating the source material as sacrosanct, mirroring Marc Brown’s book layouts verbatim to create a seamless book-to-screen transition.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot & Character Dynamics

The game adapts Brown’s Arthur’s Reading Race premise: Arthur (voiced by Ben Ellis) bets sister D.W. (Elizabeth Telefus) that she can’t read ten words during a walk through Elwood City, with ice cream as the reward. This simple conflict belies a rich exploration of sibling rivalry, emergent literacy, and persistence. Arthur embodies the skeptical mentor, while D.W.’s bravado—masking genuine vulnerability—offers a relatable arc for young players. Supporting characters like the loyal dog Pal add comic relief, but the true antagonist is language itself—a hurdle D.W. vaults with trial-and-error clicks.

Themes & Educational Philosophy

The game’s genius lies in its thematic layering:

– Intrinsic Motivation: Ice cream isn’t just a reward; it’s a metaphor for the sweetness of literacy.

– Agency & Mastery: Players assist D.W. in self-directed learning, reinforcing autonomy.

– Social Learning Theory: Hidden animations (e.g., storefront gags) model real-world reading applications.

Dialogue—lifted from Brown’s prose—prioritizes conversational cadence over didacticism. Notably, a teacher character warns, “Words are more powerful than you can imagine,” underscoring the game’s reverence for language.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Interactivity Loop

The game operates across two modes:

1. Story Mode: Pages turn via arrow clicks, with fully voiced narration.

2. Interactive Mode: Players click words to hear them spoken, hunt hidden animations, and unlock minigames.

Mini-Games as Learning Scaffolds

– I-Spy: Vocabulary reinforcement via environmental object hunts (e.g., “Find something purple”).

– Word Match: Flashcards pairing nouns with images, adjustable for difficulty.

– Board Game Race: A Chutes and Ladders-inspired race where players advance by spelling words—substituting rote counting with phonetic awareness.

UI & Accessibility

The interface exemplifies child-centric design:

– Minimalist Toolbar: Icons depict actions (speaker for narration, book for help).

– Error Tolerance: Misclicks trigger playful animations, not punitive resets.

However, the lack of save/load functionality (a constraint of 1997 installs) meant sessions had to be completed in one sitting—a flaw mitigated by short playtimes (20–30 minutes).

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design

Living Books’ artists preserved Brown’s watercolor aesthetic—all warm ochres and tactile textures—while amplifying dynamism through frame-by-frame animation. Each of the 28 scenes bursts with secondary motion: flickering streetlights, rustling leaves, and characters who blink or fidget if idle. D.W.’s exaggerated expressions (eye-rolls, triumphant smirks) anthropomorphize literacy’s emotional stakes.

Sound Design & Acoustics

Bob Marshall’s soundscape harmonizes diegetic realism (chirping birds, clinking ice cream shop bells) with playful abstraction (cartoonish boings for misclicks). Voice acting straddles theatricality and relatability, particularly Pal’s panting (Philo Northrup) and D.W.’s petulant delivery. The soundtrack—a mix of jazz loops and piano motifs—subtly shifts tone during minigames, cueing urgency without stress.

Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception

Critics lauded its charm but debated educational efficacy (73% aggregate on MobyGames):

– All Game Guide (90%): Praised the board game mechanic as “a masterclass in stealth learning.”

– Macworld (69%) noted that children often brute-forced solutions, questioning retention.

– Player reviews skewed higher (4.4/5), emphasizing replayability via Easter eggs (e.g., clicking the moon triggers a UFO cameo).

Long-Term Influence

Arthur’s Reading Race crystallized Living Books’ formula—literary fidelity + emergent gameplay—later refined in Arthur’s Computer Adventure (1998). Its legacy endures in:

– Modern Interactive Storybooks: Apps like Epic! replicate its word-tapping mechanics.

– Narrative Games for Dyslexia: Tools like Lexico use similar audiovisual pairing.

A 2023 Steam re-release (preserving original assets) testifies to enduring demand, though controversies linger—notably, bundled spyware in later editions via Arthur’s Thinking Games (1999), flagged by U.S. Congress for privacy breaches.

Conclusion

Arthur’s Reading Race remains a paradigm of 90s edutainment ambition—a title that respected children’s intellect while indulging their whimsy. Its flaws—shallow challenge depth, dated UI—are eclipsed by pedagogical intentionality and artistic cohesion. In video game history, it stands not as a mere footnote but as a vital hyperlink between print literacy and digital interactivity. For educators and nostalgists alike, its lesson endures: learning is not a chore but a race—one best run with joy, curiosity, and the promise of ice cream.