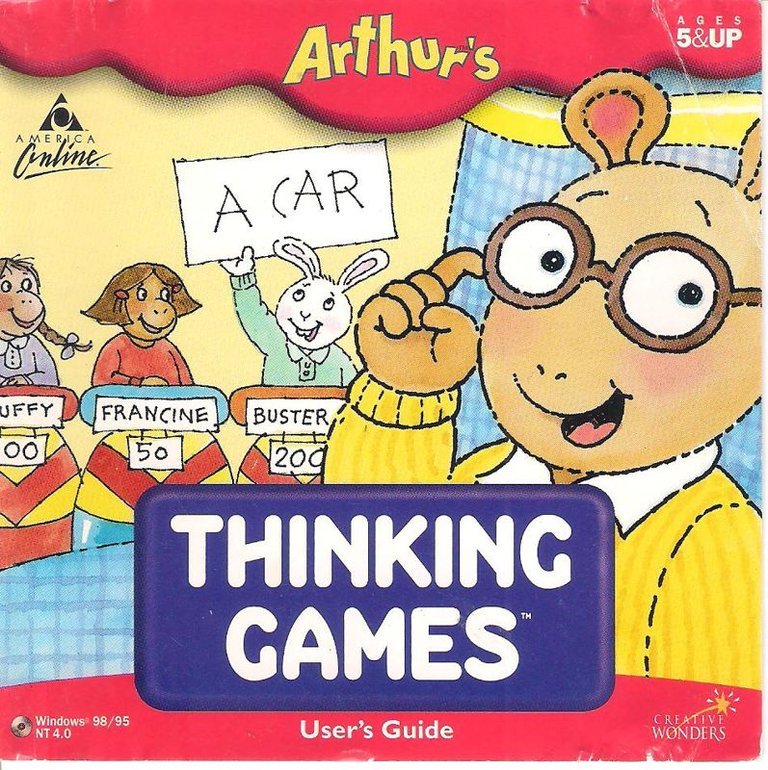

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Creative Wonders LLC, Global Software Publishing Ltd., Jordan Freeman Group, LLC, Learning Company (UK) Ltd., The, Wanderful Inc.

- Developer: ImageBuilder Software, Inc.

- Genre: Ecology, Educational, Geography, logic, Math, Nature, Science

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Dance choreography, Estimation, Logic skills, Puzzle solving

- Average Score: 86/100

Description

Arthur’s Thinking Games is an educational video game based on the popular children’s television series, featuring six engaging activities designed to develop critical thinking, logic, and problem-solving skills. Set in the familiar world of Arthur and his friends, players tackle challenges such as helping Buster locate Pal in a Roman stadium using ‘hot and cold’ clues, guiding a mummy through a pyramid maze, estimating distances to drench a dragon with water balloons, answering puzzle questions posed by Mr. Ratburn, and creating performances at the Dance Theater. Each activity offers five adjustable difficulty levels, making the game suitable for a range of ages and skill sets, while incorporating core educational themes in math, logic, ecology, science, and geography. Originally released on CD-ROM in 1999 by The Learning Company and later re-released digitally in 2025, the game blends fun, interactive gameplay with curriculum-aligned learning.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Arthur’s Thinking Games

Arthur’s Thinking Games Free Download

Patches & Updates

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (86/100): Average score: 4.3 out of 5

arthur.fandom.com : Playing and learning with Arthur and his friends is always fun.

backloggd.com : oh my god I remember playing this in kindergarten.

Arthur’s Thinking Games: Review

Introduction: The Enduring Appeal of Playful Cognition

In an era when edutainment was grappling with the fundamental question—can a game be both fun and educational without sacrificing either?—few titles on the market dared to wear both hats as proudly, or as successfully, as Arthur’s Thinking Games (1999). Released by Creative Wonders and published by The Learning Company, this often-overlooked gem from the late 1990s stands as a landmark in cognitive edutainment, a testament to the power of licensed IP married to authentic, age-appropriate pedagogical design. While the 1990s saw a flood of educational software—ranging from the clunky and didactic to the commercially viable but creatively bankrupt—Arthur’s Thinking Games carved out a niche that was both thematically cohesive and mechanically diverse. Its thesis is not that games should teach, but that thinking itself is a joyful act, and that young minds thrive when challenged through narrative, interactivity, and incremental difficulty.

Based on Arthur, the beloved PBS children’s series created by Marc Brown, which had already achieved cultural resonance for its emotional literacy, social awareness, and gentle humor, the game leverages the show’s characters to explore critical thinking, estimation, deductive reasoning, spatial reasoning, and creative expression—not through rote drills, but through purpose-built minigames that resemble the playful logic of Portal or Zork in miniature. Far from being a mere promotional tie-in, Arthur’s Thinking Games is a rare example of educational software that respects its audience, opting for formative assessment, adaptive learning curves, and cognitive scaffolding rather than punitive scoring systems or glitzy animations devoid of substance. Its legacy, though subtle, resonates in the DNA of modern games like LittleBigPlanet, Toca Kitchen, and Beecademy, which prioritize creative problem-solving over memorization. This review seeks to elevate Arthur’s Thinking Games from the footnotes of gaming history to its rightful place: a pioneer of holistic, developmentally appropriate, and technically competent cognitive gaming.

Development History & Context: The Birth of a Cognitive Franchise

The Studio: Creative Wonders & The Learning Company’s Edutainment Empire

Arthur’s Thinking Games emerged from Creative Wonders LLC, a studio under the broader umbrella of The Learning Company (TLC), a dominant force in educational software during the late 1990s. Founded in 1984, The Learning Company had already built a reputation for its ClueFinders and Reader Rabbit series, which blended gameplay with academic instruction. Creative Wonders, operating as a dedicated early-learning division, was tasked with creating play-based, developmentally appropriate software for children aged 4–8. By 1999, they had launched a full Arthur video game series, including Arthur’s Preschool, Kindergarten, 1st Grade, and Reading Games. Thinking Games was both a culmination and an evolution—a title that shifted focus from academic subjects (reading, math, grammar) to meta-cognitive skills: logic, estimation, and problem-solving.

The development team, as idenitified via MobyGames and comprehensive credit listings, was surprisingly large for a children’s game of the era, involving 90 individuals, including 84 developers and six acknowledgments. The depth of roles reveals a commitment to quality: from art direction (Shannon Keegan) and software engineering management (Hugo Paz) to QA lead (Jake Harrison) and online help (Solveig Zarubin), the studio treated this as a full-scale production. Notably, Dee Bradley Baker (later a perennial figure in animation, voicing everyone from Clone Troopers to Avatar’s cuatro backgrounds) lent his voice to Mr. Ratburn, while Mary Kay Bergman—already famous for Gargamel and Daria—voiced D.W., Francine, Muffy, Prunella, Sue Ellen, and The Brain with her signature emotional range and vocal precision.

Technological Constraints: CD-ROM, Windows 98, and the Burden of Accessibility

The game shipped in mid-1999, primarily for Windows 95/98, a time when the average home PC ran on a Pentium processor (133–266 MHz), 32–64 MB RAM, and a basic 4-8 MB graphics card. The CD-ROM medium was still standard, and Arthur’s Thinking Games leveraged its 650 MB capacity for high-quality voice acting, animated cutscenes, and rich backdrops—a significant upgrade from floppy-distribution or early-shareware games. However, this also meant high system demands for the era, which foreshadowed the game’s notorious reputation for crashes and graphical glitches, as documented in modern user reviews (“It crashed my PC and fucked up the graphics. THANK YOU ARTHUR 😡” – Lokuz, Backloggd). The reliance on animation, real-time switching between six distinct modes, and palette transitions between difficulty levels likely overloaded weak units, particularly those without proper DirectX 7 support.

Yet, Creative Wonders ingeniously accommodated low-end machines by:

– Using frequent difficulty scaling (each game starts simple) to reduce cognitive load.

– Employing 2D sprites on 3D-rendered backdrops—a compromise between visual fidelity and performance.

– Offering a launcher with all activities on one screen, avoiding the need for deep navigation or resource-heavy loading screens.

The Gaming & Educational Landscape: Edutainment’s Crucible

In 1999, edutainment was in a state of flux. The mid-90s had seen programs like Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing and Math Blaster define the genre, but they were often overly mechanical, academically rigid, or visually uninspired. Meanwhile, mainstream gaming catered to teens and adults (Half-Life, EverQuest, Final Fantasy VIII), leaving young children with a void. PBS, recognizing the potential of interactive media, had already partnered with The Learning Company for the LearningBuddies line, which Arthur joined in 1997.

The market was skeptical. As Forbes (1999) questioned, “Is wrapping up educational content under the guise of video games featuring children’s characters like Arthur and Dr. Seuss enough to entice parents with the promise of easy learning for their kids?” Critics feared exploitative brand saturation and superficial learning. But Arthur’s Thinking Games answered this with pedagogical integrity. Unlike Dr. Seuss ABC or Reader Rabbit, which focused on letter recognition, Thinking Games pioneered executive function development—skills like judgment, spatial cognition, and pattern recognition, which are increasingly recognized as foundational to long-term academic success.

Notably, the game was developed with educators and aligned with core curriculum standards, a fact emphasized in press materials. This collaborative approach—typical of the whole Arthur series—elevated it above many contemporaries, which were either abandoned by publishers after one release or suffered from poor educational design.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Logic as Play, Play as Logic

The Framing Device: Mr. Ratburn’s Puzzlers – A Cognitive Theater

The game opens with Mr. Ratburn, the beleaguered but brilliant fourth-grade teacher, hosting a quiz show called Mr. Ratburn’s Puzzlers. This meta-narrative device serves as both a thematic and functional backbone. Students are invited to become “Super Duper Smarty Pants” (a term later echoed in Khan Academy and Gamestar Mechanic), earn badges, and progress through five difficulty tiers. The quiz format isn’t just a shell—it frames the entire experience as a journey toward intellectual mastery, reinforcing the game’s ethos: curiosity is rewarded, effort is noticed, and growth is celebrated.

Each minigame maintains a narrative wrapper:

– Where’s Pal?: Buster hides his dog Pal in a mythologized “Roman Stadium,” and the player uses “hot” and “cold” clues to locate him—a classic search-and-reason puzzle inspired by ancient logic games and modern UI “find the hidden object” mechanics.

– Muffy’s Mummy Maze: Muffy claims to have found an ancient mummy (a product of her well-documented narcissism and boasting) and challenges the player to navigate it out of a 3D-isometric pyramid with locked rooms, keys, and pressure pads—echoing Tomb Raider and Maniac Mansion with kid-friendly logic.

– Drench the Dragon: D.W., in a siege on a cartoonish castle, operates a water balloon catapult to douse a roaring dragon. The theme blends fantasy, physics, and estimation—the trajectory puzzle here is a progenitor of Angry Birds’ physics engine, but grounded in real-world projectile motion concepts.

– Dance Theater: Arthur performs choreographed dance sequences in front of player-designed backdrops. This is not a math or logic puzzle, but a cognitive sandbox—players program dance moves in a sequence, thereby practicing sequencing, pattern recognition, and causal reasoning, all disguised as art.

Thematic Throughlines: The Mind as a Playground

The overarching theme is cognition as exploration. Unlike games that treat the brain as a warehouse to be filled, Arthur’s Thinking Games positions it as a lab, canvas, or strategy map. Key themes include:

- Estimation Over Precision – In Drench the Dragon, there’s no target indicator; players must estimate trajectory, wind resistance, and force—a nod to probabilistic thinking.

- Pattern Recognition – Mr. Ratburn’s Puzzlers often ask questions like, “Which of these animals is a mammal?” encouraging categorical thinking.

- Spatial Intelligence – The maze game uses isometric perspective, requiring mental rotation and pathfinding—a precursor to spatial reasoning in STEM fields.

- Creative Confidence – The Dance Theater allows unrestricted color, shape, and movement, reinforcing that expression is a form of cognition.

Character Agency & Emotional Resonance

Crucially, the characters are not set dressing. Each minigame embodies a personality trait:

– Mr. Ratburn = intellectual rigor

– Buster = curiosity and persistence

– Muffy = confidence (or overconfidence, in mummy’s case)

– D.W. = independence and cleverness

– Arthur = creativity and rhythm

Their dialogue is scripted to offer hints, encouragement, and sly jokes (e.g., D.W. yelling, “You call that a drawbridge?!” during the catapult scene), creating emotional investment that tricks the brain into persistence. The game avoids the “do another level or you fail” trap of other edutainment titles, instead using positive reinforcement and automatic difficulty adaptation (a rare feature in 1999 software).

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Symphony of Six Games

Core Gameplay Loops: Incremental Complexity & Adaptive Challenges

Each of the six activities shares a common structure:

1. Objective presentation via character dialogue.

2. Tutorial frame (often verbal).

3. Player interaction with 3D-isometric or 2D environments.

4. Feedback system (clapping, dialogue, visual cues).

5. Difficulty scaling (Levels 1–5).

The game uses a laddered learning design, where each level:

– Introduces one new mechanic (e.g., obstacles, time limits, labels).

– Removes one support (e.g., hints before clicking, fewer choices).

– Increases cognitive demand (e.g., more guesses in “hot-cold” mode).

Example: Where’s Pal?

– Level 1: 2×2 grid, 4 guesses, immediate “hot” response.

– Level 3: 4×4 grid, 8 guesses, delayed delay, “warm”/“cold” only.

– Level 5: Wrapping edges (like a toroidal grid), 10 guesses, decreasing clue specificity.

This gradual complexity mimics Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development—learning just beyond the child’s current skill.

Game Modes in Detail

| Game | Core Mechanic | Cognitive Skill | Innovation/Flaw |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mr. Ratburn’s Puzzlers | Multiple-choice trivia | Word recognition, categorization | Wide range of topics (ecology, math, nature) ✅ Adaptive: wrong answers show correct choice |

| Where’s Pal? | Hot-cold grid search | Deductive reasoning, estimation | Isometric grid with columns/rows ✅ Hints reduced over levels ❌ Limited palette (gray/brown) |

| Muffy’s Mummy Maze | Key-and-door pathfinding | Spatial reasoning, planning | Isometric puzzle with hidden keys ✅ Great feedback (“Look under the sarcophagus!”) ❌ Unresponsive controls on slow PCs |

| Drench the Dragon | Physics-based catapult | Estimation, cause-effect | Trajectory arc visualization ✅ “Try again” feedback is gentle ❌ No advanced tools (e.g., angle ruler) |

| Dance Theater | Chained movement programming | Sequencing, creativity | Pixel-style backdrop editor + move sequencing ✅ Pure open-ended play ❌ Limited move set (6 actions) |

| Unlabeled 6th Activity | Implied “bonus” (unused) | N/A | N/A (likely was cut; per Arthur Wiki, Dance Theater functions as both art and logic mode) |

UI, Feedback, and Accessibility

The UI is minimal but highly effective:

– Central launcher with thumbnail previews of each game.

– No menu overload—options are drop-down, voice-based, or icon-driven.

– Visual cues (glowing buttons, shrugs for wrong answers, smiles for correct).

– Accessibility: All games use mouse or keyboard only—no touch, no controller required. However, no save system or profile switching limits long-term use.

Innovations & Flaws

Innovations:

– Auto-levelling: One of the first edutainment games to dynamically adjust difficulty based on performance.

– Narrative feedback: Characters react to performance (“Great guess, Francine didn’t know that!”).

– Creative-cognitive fusion: Dance Theater is the first instance of art as logic training.

Flaws:

– Crash-prone: The game installs “DSS Agent” (Digital Subscriber Service), labeled as spyware by the U.S. News & World Report, due to its background communication and online update claims (even if not always functional).

– Buggy graphics: Some machines lose sprites or color depth; reviews on Backloggd and MobyGames cite “fucked up the graphics.”

– Limited online features: The “free Arthur screensaver” download (mentioned in Arthur fandom) was the source of many privacy concerns.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Visual Language of Early Learning

Visual Direction: Watercolor Meets Cartoon Tech

The art style is a hybrid of children’s book aesthetics and limited 3D rendering:

– Characters: Designed to match the Arthur TV show’s watercolor, hand-drawn look, with expressive faces and exaggerated body language.

– Environments: The Roman Stadium and pyramid use isometric projections with rendered 3D polygons, but textured to resemble toy dioramas. This creates a “dream logic” world—familiar, structured, but fantastical.

– Dance Theater Backdrops: Titles like A Tropical Vista, An Egyptian Scene, The Great Outdoors suggest cultural storytelling, turning graphic design into narrative space.

The five backdrops in the Dance Theater are geographically themed, subtly teaching spatial and cultural awareness—a rare touch in a thinking game.

Sound Design: Audio as Learning Tool

The soundscape is deliberately designed to focus attention:

– Voice acting: Mary Kay Bergman (D.W.) and Dee Bradley Baker (Ratburn) perform with emotional clarity, crucial for auditory learners.

– Sound effects: Each click, bounce, and balloon pop is precise and tactile, reinforcing cause-effect relationships.

– Music: Light piano, cheerful strings, and bouncy melodies in minigames; dreamy synths in overworlds. No music is annoying or overpowering—prioritizing speech.

Notably, the game includes no background “app” sounds (like TV static), minimizing cognitive load.

Atmosphere: Safe, Predictable, But Not Boring

The setting is Elwood City-ish, but abstracted—like a child’s memory of school, park, and castle. It’s safe, bright, and inviting, without the creepiness of LittleBigPlanet’s factory or The Stanley Parable’s surrealism. The palette is warm: yellows, blues, and greens dominate. This creates a psychological safety net for young learners.

Reception & Legacy: From School Labs to Digital Rediscovery

Commercial & Critical Reception (1999–2002)

Arthur’s Thinking Games was a commercial success, ranking:

– #9 top-selling software in September 1999 (PC Data)

– #1 home education software for that month

Critics were divided but respectful:

– Discovery Education called it “edutainment at its best” (Arthur’s 2nd Grade review, often used as comparison).

– SuperKids acknowledged its appeal but noted “veteran gamers will be unimpressed”.

– MacWorld (1999) praised its “rewarding, albeit overwhelming, design.”

– Eugene Register-Guard gave the related Arthur’s Reading (4/4), setting a high bar for quality.

However, privacy concerns emerged. The DSS Agent (Broadcast) program, included on install discs, was labeled spyware by:

– The Congressional Record (2000)

– U.S. News & World Report

– The New York Times

The agent was allegedly for remote updates and analytics, but child safety groups criticized its background operation and data collection.

Reputation Over Time: A Cult Classic Reborn

Initially derided as “for schools only,” the game found nostalgia-driven rediscovery in the 2010s through:

– Internet Archive preservation (multiple ISOs uploaded, 2017–2022)

– Backloggd & MobyGames archives (user memories: “played in kindergarten”)

– Modern re-releases:

– ZOOM Platform Media digital port (March 1, 2025)

– Steam release (March 14, 2025, curated by Digital Museum of Digital History)

User reviews, though few, express deep emotional attachment:

“oh my god I remember playing this in kindergarten…” – obsydia, Backloggd

“I thought it was fun but the computer could barely run it” – Lokuz, Backloggd

This enduring personal resonance—not just “it was good,” but “it was my game”—is a hallmark of timeless educational design.

Industry Influence: Foreseeing Today’s Trends

Arthur’s Thinking Games anticipated:

– Cognitive play games (Toca Life, Beecademy)

– Creative coding tools (Scratch, Kodu)

– Physics-based puzzles (Air Bender, Marbles)

– Personalized learning (auto-levelling, now standard in Prodigy, i-Ready)

It also influenced modern PBS apps, such as the PBS KIDS Play suite, which uses similar minigame structures and narrative framing.

Conclusion: A Giant Under the Radar – The Game That Thought for Us

Arthur’s Thinking Games is not merely a relic of the CD-ROM era. It is a pioneering cognitive engine, a game that taught the brain how to think, not what to think. Its narrative cohesion, mechanical diversity, pedagogical intentionality, and aesthetic warmth set a benchmark that remains unequaled in commercial educational software. While it suffered from technical limitations, privacy missteps, and limited critical visibility, its core idea—that learning is play, and play teaches—transformed edutainment.

In a world where TikTok algorithms and Alexa assistants rewire cognition on the fly, Arthur’s Thinking Games offers a counterpoint: cognitive development through structured, playful, human-centered design. It didn’t just respond to the demands of 1999 pop pedagogy—it defined the vision.

Final Verdict:

Arthur’s Thinking Games is the most intelligent, emotionally intelligent, and developmentally sound educational game of its generation. It is a must-play for anyone interested in game-based learning, cognitive science, or the preservation of childhood joy in the digital age. Restored, re-released, and re-evaluated, it earns not just nostalgia, but a permanent place in the video game canon—not as a forgotten title, but as a quiet revolutionary.

Rating: 5/5 – A timeless artifact of cognitive play.

Historical Significance: ★★★★★

Replay Value: ★★★★★

Educational Impact: ★★★★★

Technical Execution (1999): ★★★★☆

Legacy in 2025: ★★★★★

It wasn’t “just a kids’ game.” It was a thinking machine in cartoon clothes. And for a generation, it taught them that to think was to believe in possibility—one Pal at a time, one balloon at a time, one dance move at a time.