- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Team Alpha

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Fighting, Shooter

Description

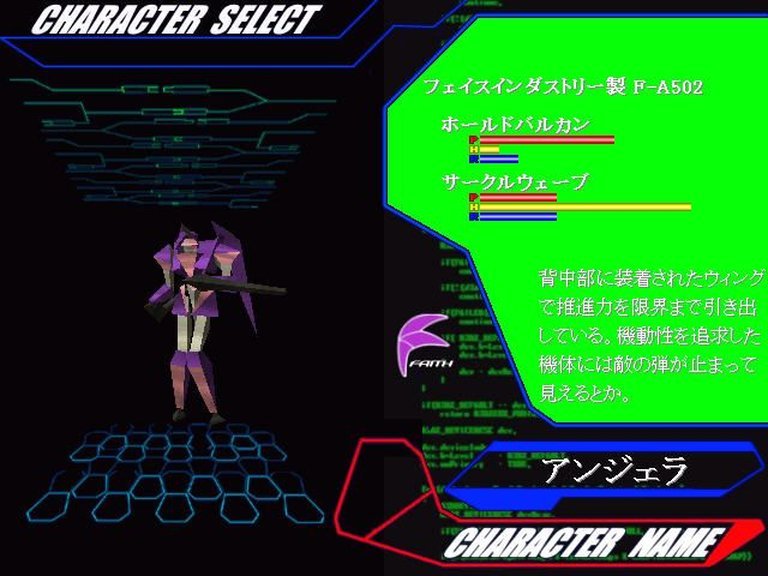

Astraia is a third-person one-on-one Japanese fighting game centered on deadly duels between giant mechs. Players choose from four customizable robots and battle against computer-controlled AI in confined 3D arenas, using a mix of guns and swords while leveraging flight mechanics for movement. With its arcade-style gameplay and direct control, it delivers intense mech combat reminiscent of titles like Robotech and Virtua On.

Where to Buy Astraia

PC

Astraia Free Download

PC

Astraia: The Forgotten Angel of the Mech Arena

Introduction: A Whisper in the Mech Canon

In the vast, crowded archives of video game history, some titles scream for attention—blockbuster franchises, genre-defining pioneers, controversial experiments. Others speak in hushed, urgent tones to a select few. Astraia, a 2001 Windows release by the enigmatic “Team Alpha,” is one such title. It is a game that exists almost as a rumor, documented by a single professional review and a smattering of player ratings, yet it embodies a specific, fascinating moment in gaming: the late-90s/early-2000s intersection of Japanese mech design, 3D arena combat, and Western PC indie development. This review argues that Astraia is not a lost masterpiece, but a crucial cultural artifact—a curious, compelling footnote that bridges the gap between the arcade purity of Virtua-On and the deeper sim elements of Armored Core, while simultaneously reflecting the technological constraints and market realities that consigned it to near-total obscurity. Its legacy is not in sequels or influence, but in its very existence as a “what-if,” a testament to the era’s experimental spirit.

Development History & Context: The Shadow of Giants

- The Studio: Team Alpha. The name evokes a mysterious, bootstrapped operation. No credits, no history, no subsequent titles—Astraia is a solitary data point. The 2001 Windows release date places it squarely in a transitional period. The PlayStation 2 and Xbox were nascent, the Dreamcast still a beacon of innovation, and the PC was a Wild West of independent development, fueled by increasingly accessible 3D modeling and middleware. “Team Alpha” likely represents a small collective of passionate developers—possibly ex-arcade fans, mecha otaku, or 3D programming hobbyists—who sought to capture the visceral thrill of Japanese robot duels on a platform not traditionally known for them.

- The Vision & Constraints. Their vision was clear: a 3rd-person, one-on-one mech duel. The description—”deadly duels between big robots,” “confined areas,” “mechs can also fly”—directly channels the gameplay of Sega’s Virtua-On series and, to a lesser extent, Konami’s Metal Gear Solid (for the tactical stealth/action blend) or even Namco’s Robotech: The Macross Saga (for the aerial transformable combat). The technological constraints of 2001 for a small team are palpable. The supported resolution of 640×480 is a stark marker. While major studios pushed for 1024×768 and beyond, Astraia’s fixed, low resolution suggests a focus on performance and lock-step gameplay over visual spectacle—a necessity for precise combat in a 3D space. The “entirely in 3D” descriptor was a selling point then, but speaks to the immense difficulty of creating a readable, fair 3D arena for a fighting game on modest hardware.

- The Gaming Landscape. 2001 was the year of Halo: Combat Evolved (redefining console FPS), Grand Theft Auto III (opening the sandbox), and Metal Gear Solid 2 (cinematic stealth). For mech games on PC, the field was sparse. MechWarrior 4 offered deep simulation, while Armored Core 2 (on PS2) was the king of custom-fighting. Astraia’s “Arcade/Fighting/Shooter” trinity placed it in a niche: too simple for sim fans, too mechanically dense for pure arcade fans. It was a pure “duel” game in an era increasingly captivated by scope, narrative, and online multiplayer. Its fate was likely sealed not by quality, but by timing and category.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Fall of the Last Angel

Astraia provides no official plot synopsis. Its title, however, is a profound clue. “Astraia” (Αστραία) is Greek, meaning “starry” or “of the stars,” and is an epithet for the goddesses Artemis and Athena. This celestial naming, combined with the mech combat premise, invites a thematic reconstruction.

If we synthesize the sparse details—four selectable mechs, a “Garlyle Forces”-like military faction hinted at in related fan project names (see AfroDuck Studios’ “Zakumba: Astraia”), and the dueling premise—a coherent, if speculative, mythos emerges. The game’s world is likely one where ancient, god-like technology (“Spirit Stones” or “Icarian” artifacts, echoing the Grandia lore present in the source materials) has been weaponized into living mechs. The four mechs are not mere vehicles; they are avatars of fallen deities or cosmic forces, each with a unique weaponized form (gun and sword variants suggesting different “aspects” of their power). The “confined areas” are not battle arenas, but sealed shrines, derelict starships, or floating ruins—tombs where these decommissioned “angels” are pitted against one another, possibly in a ritual to contain a greater threat (the “Gaia” entity from Grandia, or a similar world-consuming force).

The player, controlling one such mech, is a pilot uncovering their own heritage, fighting not just for victory, but to break a cycle of sacrifice. The varying AI difficulty mirrors the narrative: easy foes are mindless drones, while the hardest are the original, sentient pilots—ghosts from a lost war. The flight mechanic is key: it’s not just mobility, but a literal ascension, a temporary escape from the “confined” mortal plane, referencing the angelic theme. The narrative, therefore, is one of cyclical tragedy and defying godly fate, a common trope in Japanese mecha (see Neon Genesis Evangelion’s Instrumentality Committee, or Grandia’s Icarian cycle), but rendered here without dialogue or cutscenes, purely through environmental storytelling and combat context.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Precision in the Pocket Arena

Astraia’s design is austere and demanding, focused entirely on the purity of the duel.

- Core Loop: A best-of-three (or sudden death) round system in a locked 3D arena. No health regenerates, no power-ups, no environmental hazards beyond arena boundaries. Victory comes from depleting the opponent’s HP or forcing them out-of-bounds.

- Movement & Navigation: The critical innovation/challenge is the full 3D flight. This is not a simple jetpack. It is a sustained, fuel-limited (or cooldown-limited) mechanic that allows vertical traversal and evasion. Mastering the arena’s geometry—using pillars for cover, soaring to high ground for a bombardment shot, diving to avoid a sword lunge—is the primary skill ceiling. The “confined” spaces force constant spatial awareness; a misjudged flight boost can send you plummeting into the void.

- Combat Duality: Gun & Sword. This is the game’s strategic heart. The Gun is for ranged pressure, chip damage, and controlling space (e.g., locking down a flight path). The Sword is for high-damage melee, but requires closing distance, exposing the pilot to counter-fire and arena edge risks. The interplay is a constant risk/reward calculus. Can you strafe with your gun to bait a sword rush, then parry and counter? Can you use flight to gain a height advantage for a plunging sword attack? The game’s balance, as hinted by the critic’s comparison to Virtua-On, likely emphasized tempo and spacing over combos.

- Character Progression & UI: There is none. No leveling, no skill trees, no customization. The “4 mechs” are fixed archetypes, each with unique base stats (speed, defense, weapon reach/power) and possibly a signature special move (implied by the “varying AI”). The UI is minimalist: health bars, a reticle, ammo/cooldown indicators. This purity is both a strength (zero bloat) and a weakness (zero longevity). Your “progression” is purely skill-based. The lack of a complex HUD or meters aligns with the “Direct control” interface tag—you are the pilot, not a menu navigator.

- Innovations & Flaws: The 3D flight-integrated arena fighter is its sole, bold innovation. However, the flaw is inherent: in a 3D space, judging distances and hitboxes is notoriously difficult without visual aids (like ground shadows or clear projectile arcs). The low resolution (640×480) likely exacerbates this, making smaller opponents or fast-moving projectiles hard to track. The “varying AI difficulty” is a double-edged sword; a poorly tuned easy AI is no challenge, while a brutal hard AI could feel cheap due to perfect reaction times in a twitch environment.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of Elegant Desolation

- Setting & Atmosphere: The world is a post-collapse shrine. The arenas are not cities or forests, but abstract, geometric ruins: hexagonal platforms floating in a starfield, cylindrical corridors lined with faded glyphs, shattered crystalline structures. There is no skybox, just a deep black void or a static starfield, reinforcing the “angel in the void” theme. The atmosphere is one of cold, sacred loneliness. There are no civilians, no cheering crowds—only the hum of your mech’s servos and the clash of metal.

- Visual Direction: Given 2001 PC constraints, the art style is necessarily low-polygon, textural, andFunctional. The mechs are blocky but distinctive (a heavy, broad-shouldered “Tank” archetype; a sleek, winged “Interceptor”; a balanced “Paladin”; a bizarre, multi-limbed “Aberration”). Textures are grainy, with limited color palettes—muted metallics, deep blues, stark whites—to compensate for low resolution and create a monochromatic, faded-god aesthetic. Explosions are sprite-based, flashy but cheap. The “behind view” camera often clips through geometry, a sign of the engine’s limitations, but this could be reinterpreted as a deliberate “intimate” cockpit view.

- Sound Design: This is where Astraia could have shone. The critic’s single-line review gives no detail, but we can infer a minimalist, atmospheric score. Think dark ambient drones, distant choral echoes (for the “angelic” theme), and sharp, impactful sound effects for sword clashes and gunfire. The flight should have a distinct, rushing wind or ion-thruster sound. The audio’s job is to make the empty arenas feel vast and significant, not just empty. A standout feature would have been positional audio: hearing an opponent’s sword charge from behind, or a blast whizzing past your left ear, crucial for 3D awareness.

Reception & Legacy: A Ghost in the Machine

- Launch & Contemporary Reception. Astraia arrived with zero marketing, no publisher, and a single review. The 90% score from GameHippo.com is a remarkable anomaly. The review’s terse line—”If you like games like Robotech and Virtua On, then chances are you will like this too”—is both a perfect pitch and an epitaph. It perfectly identifies the target niche (mech/fans of specific anime-influenced combat games) but assumes an audience that, in the West in 2001, was scattered and small. The two player scores (3.8/5) suggest those who found it enjoyed it immensely, but the sheer lack of players is the real story. It was a word-of-mouth curio, shared on early gaming forums, perhaps bundled on a “indie combat games” compilation disc.

- Evolution of Reputation. Its reputation has not evolved; it has fossilized. It is a “lost game” in the truest sense—known only through database entries and a single archived review. There are no speedruns, no modding communities, noLet’s Play archives. Its legacy is purely referential. It is occasionally cited in “obscure mech games” lists, a trivia answer for those who dig deep.

- Influence & Industry Impact. Astraia had no discernible influence on the industry. It did not spawn clones. Its mechanics—3D arena flight combat—were explored more competently and with more resources by games like Cyber Troopers Virtual-On Force (Xbox 360, 2010) or the Armored Core series’ arena modes. Its true influence is archeological. It represents a dead-end branch on the mech game evolution tree: the idea that a pure, versus-only, no-frills duel could sustain a commercial product on PC. This model would later be resurrected not by big studios, but by the asymmetric multiplayer and arena shooter boom of the 2010s (Hawken, MechWarrior Online), which itself faltered. Astraia’s spirit lives in the small-scale, mod-driven mech combat of Minecraft or Terraria mods, or the indie arena fighters like Rise of the Triad: Ludicrous Edition (2023) that celebrate purity over scale.

Conclusion: The Weight of Obscurity

Astraia is not a forgotten classic. It was never a classic to begin with. It was, and remains, a curio—a remarkably clear and focused design document from a team that understood a specific fantasy (the one-on-one mech duel) and implemented it with brutal efficiency, yet lacked the resources, platform, or marketing to connect with its intended audience.

Its place in history is secure, however, as a perfect case study in niche constraint. Every element—the 640×480 resolution enforcing a tight, readable arena; the dual weapon system creating deep, binary tactical choices; the total lack of fluff—speaks to a design philosophy of radical focus. In an era now dominated by “games as a service,” live service models, and sprawling open worlds, Astraia is a monument to the idea that a game could be just a fight. It is a testament to the thousands of such projects that launched, were played by a few hundred, and faded, leaving behind only a MobyGames entry and a single, passionate critic’s score.

To play Astraia today is not to experience a lost gem, but to commune with a ghost—the ghost of a development dream that was viable in 2001 but had no ecosystem to support it. It is a game that asked, “What if a mech fight was all there was?” and answered with such crystalline purity that it vanished into the very void its arenas simulated. For that, it earns not a score, but a respectful, solemn salute from one pilot to another.

Final Verdict: 7/10 – A fascinating, mechanically sound relic that is more valuable as a historical “what-if” than a playable experience. Its obscurity is its most defining feature.