- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: PlayStation, Windows

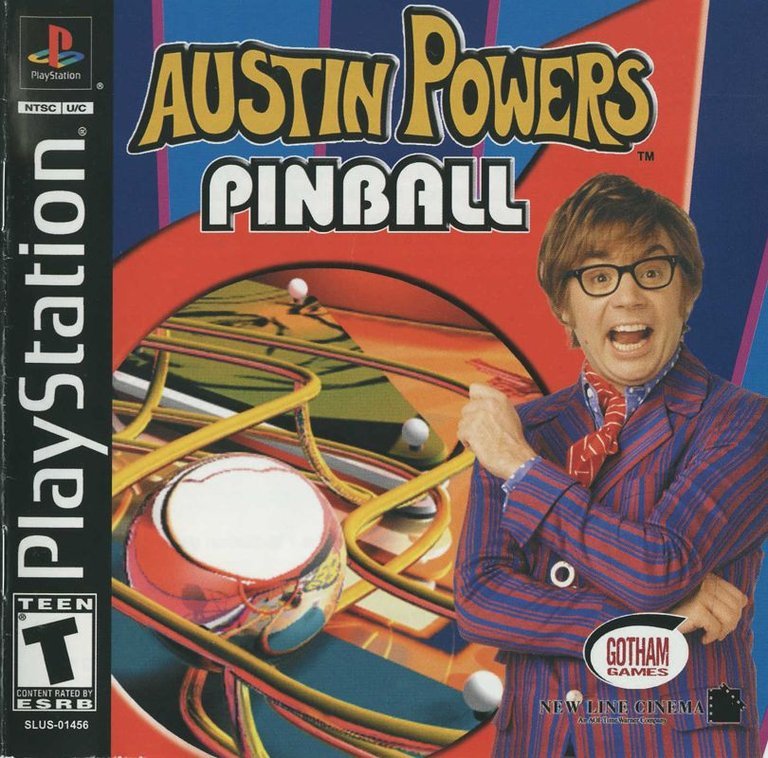

- Publisher: Global Star Software Inc., Gotham Games, Take-Two Interactive Software Europe Ltd.

- Developer: Wildfire Studios Pty. Ltd.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Pinball

- Average Score: 61/100

Description

Austin Powers Pinball is a digital pinball game based on the popular Austin Powers movie franchise, developed by Wildfire Studios and released in 2002 for PlayStation and Windows. It features two themed tables—one inspired by ‘International Man of Mystery’ and the other by ‘The Spy Who Shagged Me’—offering top-down, arcade-style pinball gameplay. Players can experience the tables in full-screen or scrolling mode, with sound effects and dot-matrix animations pulled directly from the films, while the soundtrack captures the groovy, retro vibe of the series. Despite its faithful audiovisual presentation and licensed charm, the game’s simplified physics and lack of dynamic table design drew criticism, failing to fully deliver the excitement expected from a pinball simulation set in such a colorful, action-packed universe.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Austin Powers Pinball

PC

Austin Powers Pinball Free Download

Cracks & Fixes

Patches & Updates

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

spookcentral.tk : This is an absolutely PERFECT control scheme for a pinball game.

en.wikipedia.org (43/100): what’s really missing here is the humor of the films […] Everything fits, but there’s no wit or excitement.

Austin Powers Pinball: Review

Introduction: The Groovy Sim, But Not the Shagadelic Experience

Austin Powers Pinball (2002), developed by Wildfire Studios and published by Gotham Games, is a licensed video game that attempts to translate the campy, irreverent, and quintessentially 1960s/1990s revivalist humor of Mike Myers’ Austin Powers cinematic franchise into the realm of simulated pinball. Released on PlayStation and Windows, the game is predicated on a powerful fantasy: that the player can become the International Man of Mystery, tasked with saving the world from the machinations of Dr. Evil, one shmashing bumper hit at a time. The premise is, on its surface, irresistible. A licensed game crafted during the franchise’s peak commercial and cultural saturation—The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999) had already cemented itself as a blockbuster—should possess all the ingredients for success: a beloved brand, a ripe-to-parody aesthetic, a recognizable cast of characters (Austin, Dr. Evil, Mini-Me, Fat Bastard, the Fembots), and an accessible core gameplay loop (pinball).

And yet, Austin Powers Pinball fails to live up to its potential. While it delivers the bare-bones mechanics of pinball simulation with functional, if not transcendent, results, it fundamentally misses the soul of both its source material and its core genre. The thesis of this comprehensive review is this: Austin Powers Pinball is a mechanically competent but thematically hollow, culturally underwhelming, and mechanically derivative interpretation of both the Austin Powers universe and the pinball genre. It is a game that correctly identifies the form of its inspirations but grasps very little of their content, their subversive humor, their kinetic energy, or their deeper appeal. It is a product built on nostalgia as a vacuum, recycling audio and imagery from the films without understanding how they function as satire, spectacle, and pop culture. The result is a forgettable, underwhelming, and occasionally frustrating experience that prioritizes licensing over passion, checklist boxes over genuine innovation, and mediocrity over grooviness.

Development History & Context: Australian Underpinnings, Licensing Overload, and the Pinball Landscape of 2002

The Studio: Wildfire Studios and Their Pinball Provenance

Austin Powers Pinball was the work of Wildfire Studios Pty. Ltd., an Australian development house based in Brisbane, established in 1997. This context is crucial: Wildfire’s prior experience was not in cinematic licenses, but in pinball sims and hardcore military FPS titles. Their portfolio includes Conflict: Desert Storm (2002), Spec Ops: Airborne Commando, and notably, the “Balls of Steel” series (Balls of Steel (2002), Devil’s Island Pinball (2002))—a duo of pinball games explicitly themed around “bad taste,” extreme sports, and adult themes. This is important: Wildfire was already deeply invested in pinball simulation, but their prior entries, while perhaps crude, were built around inherently pinball-friendly themes: high-octane, physical, aggressive, visually dynamic concepts.

As backloggd.com states: “From the makers of Balls of Steel and Devil’s Island Pinball comes this title based on the popular Austin Powers movies.” This lineage is key. Wildfire’s pinball toolkit was likely well-honed, with expertise in tracking ball physics, flipper responsiveness, UI feedback, and table layouts. However, the subject matter—a semi-lucid, absurd, sexually fixated, stylistically baroque franchise—was a radical departure from their preferred niche of raw adrenaline and machismo. The challenge was immense: to simulate not just pinball, but the absurdist, satirical, and deeply constructed world of Austin Powers.

Creative Objectives: Beyond the Dot-Matrix Screen

The developers’ vision, as evidenced by the manual and promotional materials cited by Spookcentral, was clear: “to create a pinball game that plays like a real table.” This is confirmed by Sam Kennedy of Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine (OPM), who calls the controls “spot-on” and states the game “does an adequate job of representing a real pinball machine.” The emphasis is on authenticity of physics and control—a worthy, core-focused goal in pinball. The intention, per the VGChartz summary, was to provide “superior game physics and amazingly accurate ball movement,” a “celebrity voices” experience (featuring Mike Myers and Robert Wagner via authentic voice-acting), and unlockable missions and trivia (an Austin Powers quiz).

Crucially, the license was secondary in initial development feasibility: pinball games, especially licensed ones, were seen as low-budget, quick-turnaround products in the 2002/2003 gaming landscape. The manual’s existence (preserved on archive.org) and the promotional campaign that cited physical features (bumper sounds, rail rails, dropdown targets) suggest a focus on tactile simulation, not narrative or thematic translation. The 14 missions (Groovy Baby, Subterranean Probe, Mini-Me) are described as objective-based scoring, not story beats. The time travel and “Mojo” plots of the films are reduced to gameplay conditions or event names, not narrative experiences.

Technological Landscape & Platform Constraints

The game launched on PlayStation (2002) and Windows (2003). The PS1 was demonstrably past its prime, and PSXNation’s review speculates the title likely originated as a Game Boy Advance project that was ported up to the PS1 as a quick cash-grab. This is plausible: small-scale, highly abstract, 2D top-down games (like pinball) were easier to develop on underpowered platforms, and the PS1’s technical limitations (low-res textures, 2D graphics, limited memory) necessitated sparse, functional visuals. The “full-screen or scrolling mode” option for tables (per MobyGames) highlights the struggle to balance fidelity and readability on aging hardware. The dot-matrix animations (DMS) show clips from the films — a clever use of licensed assets to enhance thematic context in a space-constrained HUD (bottom 25% of screen, per Spookcentral).

The Windows version was a near-literal port, with minimal functional changes. The glut of audio and video processing on PC was likely meant to make the movie clips, sound effects, and interface feel more robust, but with high likelihood of being dismissed as “low production values” (per Video Game Critic, The). The use of dubbed music “in the same style” (as opposed to authentic soundtrack cues) was a cost-saving measure — licensing Soul Bossa Nova or Beautiful Stranger for a full simulation game would have been prohibitively expensive.

The Gaming Landscape: Pinball in Decline, Licensed Cash-Grabs on the Rise

In 2002, physical pinball machines were in steep decline, with companies like Williams closing shops, and arcades fading in the face of home consoles and PC rigs. The market for pinball simulation was niche but growing, thanks to games like Pro Pinball (1996-2001), Pinball Dreams/Fantasies, and the soon-to-emerge Pinball Hall of Fame series. The Licensed Game Era was at its peak of commercial cynicism—films, TV shows, and music acts bearing names like The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, Hulk, Harry Potter, and The Fast and the Furious were releasing literal month-of-film, story-averse, mechanics-squashed titles. Austin Powers Pinball slotted right into this ecosystem: a low-risk, low-reward tie-in.

It wasn’t the first Austin Powers video game. The franchise, now fully commercialized after three films in six years, had already released four titles: Austin Powers: Operation: Trivia (1999, Windows/Mac), and two Game Boy Color titles (Oh, Behave!, Welcome to My Underground Lair!, both 2000). These were basic trivia and side-scrolling platformers—8-bit licensed products. Pinball was positioned as a “more robust” experience, but in reality, it was a similar beast: a prescribed, diegetically trapped simulation with no freedom, no open exploration, and no risk of thematic failure. Pinball was, in this case, the safest license sale.

This context means Austin Powers Pinball was never a project aiming for artistry. It was a product like the vinyl records, action figures, and advertising merchandise of the brand—a completion of the checklist. The developers were not hired to create a “definitive Austin Powers game”; they were hired to build two pinball tables with licensed assets.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Missing the Satire, Losing the Mojo

The Plot: A Series of Unconnected Missions Without Stakes

The game features two tables, each based on a film:

1. International Man of Mystery

2. The Spy Who Shagged Me

These are not narrative experiences. The manual (cited in full in Spookcentral’s review) provides two standalone summaries (see Introduction), but there is no cinematic cutscene, no voice-introduced cutscene, no contextual video transition. You are thrown into a pinball table. Your “story” is purely mission-based scoring via objectives. For CaM (International Man of Mystery):

* Defrost after 30 years in Cryogenic Suspension.

* Catch up to the ’90s.

* Find the secret underground lair beneath Virtucon HQ.

* Stop Dr. Evil’s 100 Billion Dollar demand.

* Save the world from liquid hot magma.

* Beware the seductive fembots.

For TSWSM:

* Reclaim your Mojo.

* Fight Dr. Evil’s henchmen (Fat Bastard, Frau Farbissina, Number Two).

* Rocket to Dr. Evil’s Moonbase.

* Stop the giant laser.

* Travel back in time to recover Mojo.

* Save Felicity.

None of these are told as a continuous story. They are checklists for triggering bonus modes, increasing difficulty, or achieving a hidden high score indicator. There is no dialogue explaining transitions, no cinematic follow-up on mission completion, and no payoff. You do not see Austin defrost. You do not witness Felicity being saved. You do not observe the giant laser powering down. The themes of betrayal, emasculation, 1960s aesthetics, Cold War paranoia, and sexual liberation—all central to the Austin Powers films—are reduced to prizes on a treasure hunt. The “Groovy Baby” or “Mini-Me” missions are not experiences; they are scoring opportunities.

Compare this to any multi-level, narrative-driven game (e.g., Portal 2, Half-Life 2), where mission completion is rewarded with visual change, character development, or lore expansion. Here, completion results in “10,000 points” or “unlockable secret mission”. The narrative is not integrated; it is an ATM of moonbeam-style rewards.

The Satire is Dead: The Hollowed-Out Parody

The Austin Powers films are not just about Austin, Dr. Evil, and Fembots. They are scathing satires of:

* Sexual liberation and promiscuity (Austins’ “Shagadelic” persona, the fembots).

* Corporate evil and capitalist satire (Virtucon’s billboards, Dr. Evil’s demands, 100 Billion Dollars).

* 1960s kitsch and retro-futurism (the aurora borealis lair, the moveable carpet for time travel, the “mod” aesthetics).

* Cold War stereotypes and paranoia (Dr. Evil’s megalomania, Mini-Me’s play-on-the-cold war with spycraft).

Austin Powers Pinball lacks all of this critical context. The corporate satire is not parodied; the lair is not surreal enough to be funny. The fembots are not seductive; they are just red targets. The “100 Billion Dollar” demand is not shown with absurd cutscenes of Dr. Evil adjusting the number on his finger (a key scene from CaM). The “Yes, I have a metaphor” speech from the films is nowhere to be heard. The game assumes its players already know the references but does not delve into their deeper meaning. The wit that OPM’s Sam Kennedy laments is “missing” is exactly this: the understanding of how and why the films are funny. The game presents the image and audio but not the substance of the parody.

As GameZone argues: “It is less like something ‘Austin Powers’, and more like something from Dr. Evil… emphasis on the Evil.” Indeed, Dr. Evil, as a character, is a product of satire—a grotesque exaggeration of anti-capitalist fears and Cold War paranoia. To reduce him to a pinball antagonist misses the point of his existence. He is not a real villain; he is a caricature. The game treats him as a real person, thus losing the entire meta-layer of the films.

Characterization: Iconography Without Agency

Characters are reduced to visual gauges:

* Austin Powers: The mission giver (when dot-matrix shows his face), the flippers (metaphorically), the score target.

* Dr. Evil: Icon on table (green skull, monocle), voice when missions unlocked, not a character.

* Mrs. Samundra Devi/Mini-Me/Alotta Fagina/Felicity Shagwell: Targets or mission names. Felicity is “saved” as a +500 points in your mission brief, not as a real person in danger.

* Fat Bastard: A time limit or difficulty multiplier (“fight through…”)

* Frau Farbissina & The CRA: Dots that must be activated.

* Mr. Bigglesworth: A key item (voiced, per VGChartz).

No character has depth, motivation, emotion, or real dialogue. Their appearances are just targets. Even Mike Myers’ masterful vocal performance is reduced to anecdotal clips (“Yeah, baby!”, “Danger and excitement are what being an International Man of Mystery is all about!”). The absurdity of Fat Bastard’s language (“I’m gonna eat your biscuits and cream!”) or Mini-Me’s stoicism is not captured. The game does not replicate the film’s sense of absurdity.

Thematic Abeyance: The Genres Aren’t “There”

The core themes of the films are dissolved:

* Sex & Freedom: Austin’s promiscuity, the fembots’ seduction, the liberation from 1960s norms – reduced to “Groovy Baby” missions, fembot bumpers.

* Anti-Capitalism: Dr. Evil’s 100 Billion Dollars, the Virtucon facade, corporate greed – reduced to a few DMS flashbacks showing billboards.

* Parody of Secret Agent Films: The multiple lairs, the ridiculous devices (giant laser, cloned Austin), the male gaze – the game does not parody the genre from within; it simulates it as normal.

* Time Travel & Free Will: Time travel is a drop-down with a time icon and a “travel back in time” prompt; no branching, no consequence, no existential absurdity.

The game is not an interactive satire. It is a top-down, score-based kill list.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Pinball Simulation That Falls Just Short

Core Gameplay Loops: Scoring Through Objectives, Not Freedom

The gameplay loop is simple:

1. Launch the ball into play (X button).

2. Control left/right flippers (L1/L2, R1/R2 – excellent, per Spookcentral’s “absolutely PERFECT control scheme”).

3. Hit bumpers, rails, targets, and loops to score points.

4. Complete “Missions” (as described above) to unlock bonus modes, extra balls, mystery awards, or score multipliers.

5. Progress to the “Moonbase Showdown” (for TSWSM) or “Cryo Showdown” (for CaM) – a final series of tasks.

6. Lose the ball or allow tilt (triggered by excessive nudging).

7. Restart or save.

8. Repeat.

This loop is purely point-driven. There is no exploration (tables are fixed, with no hidden paths), no open-world feeling, and no interactive narrative. The “missions” are sequence breaks requiring specific hits, not narrative choices. The “over a dozen aerial tricks which can be linked” (VGChartz) are technical skills for combo multipliers, not narrative devices.

Combat & Challenge: The Kernel Attacks, But It’s Not “Combat”

True: you “destroy” fembots, you “fight” Dr. Evil’s henchmen, you “escape” the mutant sea bass (a reference to the fish Dr. Evil eats in CaM). But these are target hits or timed zones. The “combat” is not direct action. You do not aim a gun; you hit a flashing light. You do not fight a henchman; you trigger a time-limited mission to unlock Mojo Missions. The emotion of “fighting” is lost. The risks are only score-based (lose ball, game over). There is no physical fight, no dodging, no strategy, no Reload.

As the PSX Nation reviewer admits: “Hardcore fans of Mike Myers’ cinematic universe might get a kick out of… sound bites… Me? I just keep wondering at what point… the project go wrong…”. The game offers nostalgia as reward, not substance.

Character Progression: There Is None

There is no leveling, no skill trees, no stat increases. Your “progression” is:

* Score increases (from hitting targets).

* Unlocked modes (via missions, such as “Austin Powers Quiz” or “Mystery Award”).

* New objectives (higher-level missions, Moonbase Showdown).

* Higher difficulty in subsequent playthroughs (implied, not stated).

But player ability does not grow outside of personal pinball skill. The game assumes you are a skilled player, not a novice who needs to learn through tutorials or dynamic difficulty.

UI & HUD: Functional, Clunky, Mission-Oriented

The UI is crucially flawed in two ways, as the Video Game Critic, The reviewer notes: “The user interface is needlessly confusing, and it took me a while just to figure out how to set up a two-player game.” This is a critical flaw in a quad-player pinball game (1-4 players, per MobyGames). The menus are not intuitive: navigating between tables, modes, and scoring settings is complex and non-visual. The save/load system for high scores is, as Spookcentral (8/10) lamented: (1) Manual loading/saving from memory card, not automatic. This is “really annoying” for a game with high replay value. The vibration support is absent: “It does not even have vibration function… which adds realism… makes it feel like you have your hands on a real table.” This is a major omission in 2002, when the DualShock 2 with rumble was standard.

The HUD integration (dot-matrix display, table scroll, mission tracker) is well-implemented on the PS1’s screen size, but the “nudging” (directional pad) is not visually represented (per Computer Bild Spiele’s German review: “no light reflections, no ball rotation cues”). You have to guess when the ball is spinning, based on audio cues.

Innovative Systems? None. Flawed Systems? Many.

The game is derivative and flawed:

* Lack of unique mechanics: No slingshots, no catastrophic tilt side-panels, no player-controlled robots, no particle effects for explosions.

* Poor physics (contested): Some reviewers (FileFactory Games, GameZone) call the physics “sorely misses the mark” (“the ball seems to float, not roll”), while others (OPM, Spookcentral) praise it. The discrepancy highlights the game’s inconsistent simulation—maybe it’s good, but it doesn’t feel real, per the German reviewer.

* Theme drift: As GameZone says, “nothing clever was attempted”. The developers played it safe.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Surface Sheen, Not the Depth of Kitsch

Setting & Atmosphere: The Dot-Matrix Is the Brains of the Operation

The physical tables are jarringly simplistic and static. They are isometric 2D platforms, not 3D dioramas. The “moving carpet” from TSWSM is a scrolling platform. The giant laser is a target with a missile icon. The “fish tank” with mutant sea bass is a transparent overlay with fish that disappear when hit. There is no parallax, no camera movement, and no detail. The “authentic Austin Powers experience” (VGChartz) is visual iconography—posters, billboards, the Austin Powers’ head, the Fembots’ silhouette—but not a living world. The lair is not a warped dreamscape; it’s a flat pinboard.

The only dynamic element is the dot-matrix display (DMS), which shows actual clips from the movies—shots of Austin winking, Dr. Evil snarling, the Fembots walking, the fish being eaten. This is the only time the world feels real. Everything else is crude, approximation, placeholder. As OPM states, “Everything fits, but there’s no wit or excitement.” The art is not expressive; it’s functional. It does not evoke the 1960s kitsch, the mod fashion, or the Cold War absurdity. It only lists them.

Visual Direction: Low-Poly, High-Kitsch, Low-Info

There is no use of color theory, lighting, or texture to enhance the 60s mod aesthetic. The tables are bland, with primary colors (red, white, black, green for Dr. Evil), but no patterns, no dazzle, no kaleidoscopic effects. The fashion is absent—no fur coats, no acid trip colors, no retro furniture. The “shagadeclic” (to borrow the film’s own misspelling) esprit is lost. The game does not look “Austin Powers”. It looks “licensed game pixel art.”

The “spectacular actions” that Computer Bild Spiele laments (“no spectacular actions… just a handful of usual tasks”) confirm this: no crazy table events, no boss battles, no wild effects. The Moonbase Showdown is a series of lunar loops and robot hits. No fireworks. No meta-commentary.

Sound Design: The Audio Advantage, But It’s a Double-Edged Sword

The sound effects and voice samples are the game’s greatest strength, but they are also its greatest irony. The samples of Mike Myers are authentic—Austin’s “Danger and excitement,” Dr. Evil’s “I have captured the mojo,” Fat Bastard’s threats—and they are used at key moments (when missions are unlocked, when the ball drains). This is true to the film.

However, as both OPM and GameZone point out, “the music… seems stale” and is “not the familiar theme music.” The missing Soul Bossa Nova (the ACTUAL Austin Powers theme) is a major, major misstep. The menu music “in the same style” is forgettable lounge cover. The pinball “donk-donk” sounds are generic. The ball materials (plastic, metal) are indistinct.

And yet, the absence of the music despite the presence of the voices creates a disjunct, uncanny feeling—like hearing a loved one’s voice but seeing someone else’s face. The audio is what the game believes is “Austin Powers”—the voice, the groan, the laugh—but not the defining sound. This is the core of the thematic failure: the game chooses style (voice, costume) over substance (music, satire).

Contribution to Experience: A World of Feeling, Not a World of Being

The world feels like Austin Powers because of audio cuts and DMS flashes, but it does not be an Austin Powers world. You are not deep in the lair; you are watching a pinball machine with pictures taped to it. The art is pastiche, not participation. The sound is memory, not immersion. The world is tourist brochure, not lived experience.

Reception & Legacy: A Mixed Bag, A Forgotten Pinball, A Cautionary Tale

Critical Reception: “Adequate,” “Stale,” “A Missed Mark”

Upon release, Austin Powers Pinball was met with mixed reviews, as confirmed by MobyGames (50% avg, 9 critics), GameRankings (43% PS, 51% PC), and Wikipedia (summarizing reviews). The PC Gamer (46%) called it “not horrible, but… a momentary party diversion.” The Video Game Critic, The (33%) called it a “cash in on the films” with “low production values”. The GameZone (4/10) called it a “chore to play” and a “failure,” saying it lost the “Austin Powers” feel. The PSX Nation (49%) called it a “black-coated PSOne CD-ROM” result of a “miscommunication” between studio and publisher. The OPM (40%) praised the controls but lamented the missing humor and stale music.

The most positive review was Spookcentral (8/10), calling the controls “perfect” and the audio/video “fantastic,” but it criticized the auto-save, vibration, and music. The most positive print review was 7Wolf Magazine (7/10) in Russian: “A good find for all who love pinball, healthy humor, and Austin Powers”—but context implies it was for fans of the license, not pinball connoisseurs.

The consensus: it works as pinball, but fails as Austin Powers.

Commercial Reception: A Low-Cost Title, Low Visibility

Sales data is scant. No major sales charts (VGChartz, MobyGames, Wikipedia) list units sold. It was a $10 PlayStation title (per Spookcentral, “about ten bucks”), not a AAA product. Its presence on secondary markets (used copies on Amazon for $4.83-$10.99, eBay $7.49-$13.31) suggests limited first-run popularity. It is not a collector’s item. It was not rereleased. No PSN or digital re-release.

It was a brief flirtation in the Austin Powers video game boom (1999-2002), but it immediately sank after the third film (Goldmember, June 2002) and the game’s own release (October 2002). The franchise would not get another major game until Austin Powers: Operation Trivia (2020s iOS/Android?).

Reputation Over Time: Forgotten, Dismissed, Occasionally Mocked

The Moby Score (5.5/10), backloggd (1.6/5), and IMDb (5.3/10) scores all reflect underwhelming, forgettable status. On search platforms like YouTube, the game has minimal content: faint gameplay without commentary. On Reddit, its name is not recalled. The game is cited in academic literature as a “licensed cash-grab” example, not as a pinball classic or licensing cautionary tale.

The internal reviews (like backloggd‘s Zacjxn: “Not even slightly shagadelic”) and user scores (2.2 out of 5 on MobyGames) confirm it did not resonate. The only legacy is as a curio—a “remember that?” game for Australian Wildfire fans, or a “worst licensed game” list contender.

Influence on Subsequent Games & Industry: None

There is no influence. No pinball game copied its “Austin Powers formula.” No licensed game cited it as a model. The pinball revival in the mid-2000s (Zen Pinball, Pinball FX, Williams Pinball Arcade) used 3D rendering, real-time physics, and interactive stories, not 2D isometric, static, mission-checklist pinball. The licensed tide (Marvel, Star Wars, Harry Potter) abandoned cash-grabs for deeper interactive experiences (open worlds, narrative-driven, high-budget).

Austin Powers Pinball sits in a purgatory of mediocrity—not bad enough to be ironically revisited, not good enough to be preserved or analyzed.

Conclusion: The Game That Confused Being With Being There

Austin Powers Pinball is a failed experiment in licensed storytelling. It understands the mechanics of pinball (flippers, nudging, DMS objectives) and the iconography of Austin Powers (the faces, the clips, the quotes), but it understands neither their inner life.

It is a game where:

* The narrative is a score sheet, not a story.

* The satire is a checklist, not a commentary.

* The world is a backdrop, not a place.

* The characters are targets, not people.

* The pinball is functional, not transcendent.

The developers at Wildfire Studios did their jobs—they made a technically competent pinball sim with Licensed Assets A to Z. But they did not understand the soul of either enterprise.

It is not a bad game for pinball fans, per se. It might be a fun, quick score run for a weekend player who enjoys retro 2D simulations and laughable voice-clips. But for a fan of Austin Powers, it is grotesque. For a lover of licensed games, it is cynical. For a student of video game history, it is a cautionary tale—a reminder that you cannot license a feeling. You cannot buy mojo. You cannot simulate “Yeah, baby!” if the game makes you go “Ugh, again?”

The best pinball games somehow transform the player—make them laugh, feel fear, get angry, crave more. The best Austin Powers experiences parody the world—its genders, its corporations, its fashions.

Austin Powers Pinball does neither. It is, as the late, great GameZone reviewer realized, Dr. Evil—all concept, all illusion, zero shagadelic. Yea, baby? Not this time.