- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ZOO Digital Publishing Ltd.

- Genre: City-building, Compilation, Strategy

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Average Score: 57/100

Description

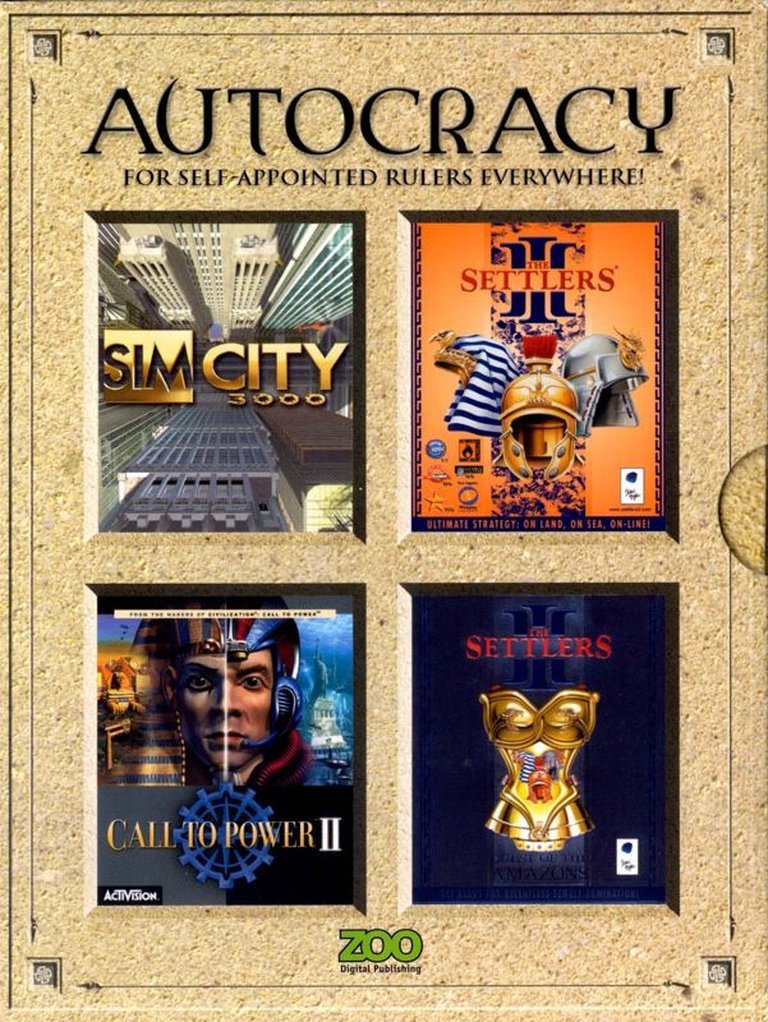

Autocracy (2002) is a compilation of classic strategy and city-building games, packaged on five CDs in a non-standard box set. The collection features a mix of real-time and turn-based simulation titles, including ‘Call to Power II’, ‘SimCity 3000’, ‘The Settlers III’, and its expansion ‘The Settlers III: Quest of the Amazons’. Designed for Windows and published by ZOO Digital Publishing Ltd., the compilation offers a diverse mix of gameplay styles ranging from urban planning and resource management to full-scale civilization building, with support for multiplayer via LAN and Internet. It serves as a versatile anthology of early 2000s strategic simulation games, ideal for fans of deep, systemic gameplay and urban or civilization development.

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (60/100): Average score: 3.0 out of 5

vgtimes.com (55/100): Gameplay: 5.5, Graphics: 5.5, Story: 5.5, Controls: 5.5, Sound and Music: 5.5, Multiplayer: 5.5, Localization: 5.5, Optimization: 5.5

Autocracy: Review

Introduction

The year was 2002, a critical juncture in the history of PC gaming. Titles like The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell, and Warcraft III were redefining expectations for depth, narrative, and innovation. Yet, amid this revolution, a quiet yet significant entry emerged—not as a single game, but as a curated anthology of emergent city-building, geo-political simulation, and economic strategy wrapped in a non-standard box. Its name: Autocracy.

This compilation, published by ZOO Digital Publishing Ltd. in the United Kingdom (and later released in Australia via Pier57 Pty Ltd.), stands as a fascinating artifact of a transitional era—one where the spirit of late-1990s simulation and strategy design was preserved, repackaged, and delivered to a new generation. At its core, Autocracy is a strategic compendium, bundling four seminal titles:

– Call to Power II

– SimCity 3000

– The Settlers III

– The Settlers III: Quest of the Amazons

Or, in the alternate Pier57 incarnation:

– Airport Inc.

– Railroad Tycoon II (Gold Edition) (with The Second Century)

– SimCity 2000 (Special Edition)

– SimTower: The Vertical Empire

My thesis is this: Autocracy is less a singular game and more a museum of simulation design philosophy—a curated retrospective of a genre whose formative years were defined by systemic complexity, emergent storytelling, and the seductive illusion of control. It is a paleontological dig into the DNA of modern city-builders and grand strategy games, a time capsule of mechanics and aesthetics that would go on to shape the next two decades of the industry. While it lacks the narrative ambition of contemporary RPGs or the visceral immediacy of action titles, its value lies not in originality, but in archival significance, curatorial intent, and the preservation of foundational design principles. To dismiss Autocracy as mere repackaging is to misunderstand its role as a cultural curator of simulation gaming—a silent but vital bridge between eras.

Development History & Context

The Publisher and the Vision

Autocracy is the product of ZOO Digital Publishing Ltd., a UK-based publisher known during the early 2000s for bundling and distributing budget software and game compilations. Their release of Autocracy in 2002 came at a moment when the physical PC game market was evolving: digital distribution was not yet dominant, but disc-based compilations were a viable strategy to extend the commercial life of aging games and appeal to budget-conscious consumers. The use of a non-standard box—five CDs instead of one, with Settlers III spanning two discs—was a bold physical statement, signaling value and volume, even if the games themselves were not new.

The title Autocracy is not the name of a new game, but rather a curation label. It hints at governance, control, and top-down authority—concepts deeply embedded in the bundled titles. This was a deliberate thematic framing by ZOO: rather than sell these games as standalone items, they were grouped under a unified ideological umbrella. The choice of name suggests a commentary—perhaps ironic—on the nature of player control in games where systems simulate societal collapse, resource scarcity, and political decay. In Call to Power II, you become the autocrat; in SimCity 3000, your role is closer to an unelected technocrat with absolute power over a model city. The title Autocracy thus functions as a meta-commentary on the latent authoritarianism built into simulation games.

Meanwhile, the Australian/Antipodean version, published by Pier57 Pty Ltd., offers a different bouquet: Airport Inc., Railroad Tycoon II, SimCity 2000, and SimTower. This suggests a regional curation strategy, targeting markets where different simulation subgenres had stronger footholds. SimTower, for instance, had not aged as well as SimCity 3000 but retained a cult following among vertical simulation enthusiasts. The inclusion of Railroad Tycoon II Gold—a 1998 title enhanced with the The Second Century expansion—was a calculated move, given its reputation as one of the most strategic and emotionally resonant resource management games of the decade (with storylines and mission-based campaigns).

Technological and Publishing Constraints

By 2002, the technology supporting these games was considered modest. The minimum requirements—Intel Pentium MMX, 64 MB RAM, 4 MB VRAM, DirectX 7.0a, and a 4x CD-ROM—reflected the specifications of hardware from the late 1990s. This meant that:

– The games were fully backward-compatible with the majority of PCs at the time.

– They avoided the bloat of new engine-driven titles, offering stable, predictable performance.

– Loading times were manageable, and UI responsiveness was not hindered by complex render cycles.

However, this also meant that no enhancements, patches, or modernization were applied. The Resizable UI, high-resolution support, and mousewheel scaling offered in Rise of Nations or Supreme Commander were absent. The games were literally what they were at original release, unaltered. There was no Overlord-like online integration or multiplayer patching—multiplayer options (LAN, Internet) merely reflected the built-in capabilities of the original games, with no added infrastructure.

The physical media—five CDs—was both a strength and a liability. On one hand, it implied value-for-money. On the other, it made the package cumbersome, and the lack of a unified menu or installer (as seen later in The Sims 2 Ultimate Collection) meant users had to install each game separately, relying on its individual launcher. This created a user experience fragmentation that undermined the idea of a smooth “compendium.”

The Gaming Landscape in 2002

The early 2000s were the golden age of strategy simulation. The Sims, Civilization III, Command & Conquer: Red Alert 2, and Heart of Darkness—all in development or freshly released—were redefining player engagement with systems, not just spectacle. The success of The Sims (2000) had proven that casual and hardcore players could find depth in simulation, energizing the broader genre.

Yet, the market was also fragmenting:

– AAA studios were investing in real-time tactics and 3D engines.

– Budget publishers like ZOO Digital filled the gap by curating older titles.

– Indie development was nascent but growing, thanks to tools like Unreal and early Garry’s Mod prototypes.

Autocracy entered this space as a curatorial intervention. It didn’t compete with Morrowind or Freedom Force; instead, it preserved the legacy of titles that were no longer front-page news. The release was not accompanied by marketing blitzes or E3 showcases, but quietly landed in retail stores, often beside budget packs from Ubisoft or EA. It was a lifeline for older games, extending their commercial viability in an era before Steam or GOG.

Crucially, Autocracy emerged at the turning point between isolated simulation and systemic integration. While Call to Power II featured early attempts at climate change, terrorism, and space colonization—inspired by Cyberpunk 2077’s designer David McCrady and the Alpha Centauri lineage—later games would merge economics, politics, and warfare into unified systems. Autocracy thus captures a moment of transition: where simulation was still modular, not holistic.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Deconstructing the Meta-Narrative of Control

At first glance, Autocracy appears to lack a unified narrative. It is a compilation, not a single story-driven experience. Yet, beneath the chaos of disparate games lies a coherent thematic red thread: the player as a singular, omniscient, and often oppressive authority figure.

Each game in the ZOO compilation—Call to Power II, SimCity 3000, The Settlers III—positions the player not as a hero or explorer, but as a de facto dictator with full control over production, employment, legislation, military, and resource allocation. The narrative framework is not told through cutscenes or dialogue trees, but emergent.

1. Call to Power II: The Technocratic Autocrat

Lead your civilization from 4000 BC to 2500 AD. This was the promise. But Call to Power II (2000) goes further than Civilization by incorporating dystopian depth. You research AI, create clones, launch orbital bombs, and incite terrorism. The AI reacts with political decisions, diplomatic intrigues, and espionage. The dialogue is minimal—advisors offer briefings—but the narrative is systemic.

– If you run low on energy, the game doesn’t warn you; rolling blackouts collapse productivity, sparking riots.

– If you build a death ray, the game doesn’t stop you; other nations declare war out of fear.

– The line between “benevolent ruler” and “tyrant” is blurred by the player’s economic necessity—your power depends on staying afloat, not on morality.

The dialogue with your advisors is procedural and reactive, often cold and bureaucratic. “Your Foreign Minister reports: Egypt proposes a Non-Aggression Pact.” The narrative is constructed in the player’s mind—a story of survival, expansion, and perhaps collapse. The theme of autocracy is self-evident: you are the head of state, with absolute authority, battling the chaos of the world.

2. SimCity 3000: The Unaccountable Technocrat

While SimCity 3000 doesn’t label you “ruler,” your role is identical. You control zoning, taxes, public works, and disaster response. The citizenry has opinions (pollution, commute times, crime) but no vote. Your advisors—Sim2Civ, Ordinances, Financial Department—offer suggestions, but you decide. The atmosphere is that of a crisis manager, dealing with tornadoes, UFOs, and bank failures. But the game subtly critiques autocracy: the longer you play, the more you realize how little you understand of emergent urban complexity. You zone commercial areas, only to see them abandoned for residential flight. Your tax hikes cause business closures. The narrative emerges: you are a puppet master in a system you cannot fully control.

The advisors’ dialogue, as documented in the VinnyVideo FAQ (2021), is a sophisticated satire of bureaucracy:

“Advisor: Highway congestion is up 12%. Consider a subway line.”

You build the subway.

“Advisor: Highway congestion is still up 8%. Consider telecommuting ordinances.”

The cycle repeats.

The narrative is one of hubris and inevitable overreach—a hall-of-mirrors reflection on leadership.

3. The Settlers III: The Benevolent Dictator with a Soft Heart

In The Settlers III, the tone shifts. You play as King of the Dark Elves, Orcs, or humans, building villages and cities through resource pipelines. The dialogue is richly voiced, with leaders giving orders and complaining about shortages. “We need more drivers! The road-side queues are the best thing to sit in and have a chat!”—a rare moment of humor in the genre.

The narrative is feudal and deterministic. You are the king; your subjects do your bidding. But the game introduces emergent psychology: miners strike if overworked, soldiers desert if morale drops, traders demand payment. The autocracy is softened by realism—you rule, but your people have agency. The expansion, Quest of the Amazons, adds a quest-based narrative, where you guide adventurers across mythical lands. The story is light, even whimsical, but still centers on a ruler sending subjects on missions—a role-playing of imperial order.

Yet, even here, the theme of political decay emerges: if you neglect infrastructure, your outposts rebel. The game punishes laziness with revolutionary mechanics, as documented in GameFAQs’ Advisor and Ordinance FAQ (2003). The advisor system—once your voice—can turn against you, delivering warnings with increasing urgency.

4. The Alternate Pier57 Packs: Vertical and Logistical Autocracy

In the Australian version:

– Airport Inc. casts you as the CEO of an airport, managing flights, baggage, and security.

– Railroad Tycoon II offers cinematic campaigns (e.g., “The Railroads That Built America”), where your success depends on cutting deals, killing rivals, and monopolizing routes.

– SimTower places you as the developer of a high-rise complex, controlling every floor—hotel, business, residential—down to the elevator system.

These games lack the historic weight of Call to Power, but they intensify the autocratic impulse. In SimTower, if elevators break, people complain. If the gym opens late, renters flee. You are God on the 76th floor, micromanaging a vertical society. The narrative is environmental and architectural—your building is the story.

Thematic Synthesis: Autocracy as a Simulated Spectrum

What unifies these disparate experiences is a spectrum of governance:

– Benevolent Manager (Airport Inc., Settlers III)

– Technocratic Crisis Fixer (SimCity 3000)

– Expansionist Conqueror (Call to Power II)

– Vertical Overlord (SimTower)

– Historical Logistician (Railroad Tycoon II)

The games never call it “autocracy,” but they embody it: one vision, no oversight, full execution. The player is never held accountable by elections, boards, or constituencies. The only limit is game-breaking failure. This is simulation at its most unmediated and authoritarian.

And that is the central irony of Autocracy: the games simulate freedom, but the player is bound by absolute control. You can change policies, but only you—no co-CEOs, no councils. The narrative is one of solitary domination, a theme later explored in Shadow Empire’s Republica DLC (2025) and Crusader Kings (as noted in Reddit, 2016): the ease with which benevolent starts turn into despotic ends.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loops: A Tripartite Model

The bundled games share a common gameplay architecture, built around three interlocking systems:

1. Resource Production Chains

- Settlers III: Wood → Sawmill → Wood

Marble → Marble Cutter → Marble

Food → Hunter → Hersy → Meat → Meat - SimCity 3000: Energy → Power Plant → Grid → Device Power

Resources → Road → Truck → Factory → Goods → Export - Call to Power II: Food → Farm → Population Growth → Tax Revenue

Production → Factory → Military Units - Railroad Tycoon II: Raw Materials → Car → Train → City → Demand → Profit

These chains rely on logistical efficiency. Break the chain—no coal for the sprinkler system—and the garden fails. Manage it well, and the city thrives. The loop is: Mine/Harvest → Transport → Process → Distribute → Reinvest.

2. Dynamic Systems and Emergent Crises

- Pollution: In SimCity 3000, smog accumulates, lowering health and attracting environmental lawsuits.

- Crime: Underfunded police leads to rising felony rates, which lowers property values.

- Disasters: Tornadoes, fires, and UFOs in SimCity, sieges and invasions in Settlers III.

- Economic Collapse: In Call to Power II, mismanagement causes inflation, population unrest, and AI-led coups.

These systems create emergent challenges that cannot be solved by checklist. They require adaptive governance, not rigid planning.

3. Issue Management and Policy Tools

Each game offers intervention tools:

– Ordinances in SimCity 3000: Subsidies, Auctions, Exclusion Zones.

– Strategic Orders in Settlers III: Force March, Siege, Scavenge.

– Political Edicts in Call to Power II: Destroy Your Essays, Ban Cloning.

– Service Ordinances in Airport Inc.: Delay Flights, Increase Security.

These tools form the player’s pocket of authority, the means by which autocracy is exercised.

Character Progression: The Absent Hero

There is no character progression in the RPG sense. No level-ups, no skill trees. Instead, progression is systemic:

– Unlocked abilities to set tax brackets.

– New construction options as technology advances (Call to Power II).

– Policy sophistication as funds allow (SimCity ordinances).

Power accumulates not in one self, but in the infrastructure and knowledge of the civilization.

UI and Accessibility: A Study in Fragmentation

Here lies Autocracy’s greatest flaw: no unified interface. Each game has its own:

– Settlers III: Detailed network of roads, robust supply drop options.

– SimCity 3000: Only Mouse + Keyboard; water zones require clicking cells.

– Call to Power II: Rich strategic map, but menu bloat.

– Railroad Tycoon II: Isometric, with excellent train pathfinding.

The lack of standardization means players must re-learn control schemes, UIs, and hotkeys for each game. There is no launcher or index—just a collection of DVDs with separate executables. This undermined the “compendium” ideal.

Yet, the individual UIs are remarkably resilient. Settlers III, in particular, with its network of roads, production lines, and demand wheels, remains one of the most user-friendly resource management interfaces of the pre-2005 era. SimCity 3000’s hand-crafted zoom levels (2x, 4x, 8x) and color-coded zone indicators were ahead of their time.

Innovation and Flaws

Innovations:

– Settlers III: Supply line management with “drop-offs” in outposts—a precursor to Satisfactory and Factorio.

– Call to Power II: AI-driven political decisions that evolve over time.

– Railroad Tycoon II: Scenario goals and narrative tracks that break linear resource loops.

– SimTower: Real-time crowd simulation in a confined space—foreshadowing Jury Duty and Hypnospace Outlaw.

Flaws:

– No unified UI (major).

– No online patching—bugs like Settlers III’s memory leaks are unchanged.

– No modern scaling—Windows NT/2K/XP compatibility issues.

– Poor bundle integration—no shared save format or cloud storage.

Yet, for a 2002 release, the sheer volume of systems was a strength. The games, though old, represent a cathedral of design that even today feels deeper than many 2025 sims.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Direction: A Century of Simulation Aesthetics

Autocracy spans three genres and decades:

– 1990s Isometric (Railroad Tycoon II, Settlers III): Pixel art, hand-animated buildings, vibrant colors, cartoonish units.

– Late 1990s/2000s Realm of the Technical Artist (SimCity 3000, Call to Power II): 3D models, dynamic lighting, detailed textures, zoomable maps.

– Vertical Simplicity (SimTower): Clean lines, segmented floors, a focus on structure over texture.

Settlers III stands out with its West European fantasy robustness. The Dark Elves have ramshackle fortresses, the Orcs have industrial brutes, the humans have gothic structures. Each biome—swamp, mountain, desert—has distinct architecture and flora.

Call to Power II’s world is atmospheric but unmagical. Its blend of Gilded Age aesthetics and futuristic technology (cyber-military, orbital bases) feels kludged, but the years run with visual fidelity—the shift from horse-drawn to space-age is palpable.

SimCity 3000 is the crown jewel. Its hand-drawn advisors—Officer Handsome, Dr. Freakweather, Commissioner Thornton—become iconic. The building models, from factories to mansions, are distinct and emotive. The weather (rain, snow, sun) changes the city’s mood. The art board—designed by the Maxis team—is a masterclass in urban animation.

Sound Design and Atmosphere

- Music:

- Settlers III: Folk-influenced, upbeat with harps and lutes—warmly familiar.

- SimCity 3000: Loop-based jazz and ambient tracks—calm but never sterile.

- Call to Power II: Orchestral with electronic elements—dramatic, over-the-top.

- Railroad Tycoon II: Ambient piano with engine sounds—reflective, melancholic.

- UI Audio:

- SimCity’s advisor calls: “Fire crews on alert!”—a cue for crisis.

- Settlers III’s truck horns and crowd noise: zombie-like yet near.

- Call to Power’s “Disaster alert!”—a death horn.

None of the games overdo it. The sound is a rhythmic accompaniment to governance, not a distraction. The absence of battle music underscores the idea that you are managing, not conquering—though conquest is unavoidable.

Atmosphere: The Weight of Control

The overall atmosphere is quiet but tense. There is no sweeping score or epic cutscene. You sit, you decide, you click. The world responds. The immersion comes from repetition and consequence: you see the smog rise, hear the siren, watch the factory close. The sound design amplifies the isolation of leadership—you are alone, making decisions for millions.

The scale is breathtaking. In Call to Power II, you manage global affairs. In SimCity 3000, you see a city grow from a village to a megalopolis. In Settlers III, your roads stretch across the realm. The world is never small—you are just one person trying to hold it together.

Reception & Legacy

Launch Performance: Silent but Persistent

Autocracy was never a critical darling. No review excerpts from PC Gamer, GameSpot, or Next Generation exist. Metacritic and MobyGames list no formal critic reviews. User ratings are sparse: 4.5/5 on MobyGames (1 rating), 3.0/5 on the Pier57 version (1 rating).

VGTimes’s 5.5/10 user average suggests middling engagement—but among a very small sample.

Yet, commercial reach was strong. Sold in major chains (Game, Foyles, Borders in the UK), it found shelves alongside Total War: Shogun and The Sims 2. The five-CD format implied depth, appealing to collectors and enthusiasts.

Legacy: The Curator of the Simulation Canon

Autocracy’s legacy is not in innovation, but in preservation and context. It:

-

Preserved Critically Reclaimed Games:

- SimCity 3000 is now considered the best in the series, with fan patches (including HD mods) in 2025.

- Railroad Tycoon II Gold was underrated in 1998 but is now praised for its blend of history and strategy.

- Settlers III has an active modding community (e.g., Autumn in the Valley mod).

-

Exposer of Design Genealogy:

- Factorio, Satisfactory, and Dyson Sphere Program owe a debt to Settlers III’s supply lines.

- Cities: Skylines has stated inspiration from SimCity 3000’s density zoning.

- Stellaris and Europa Universalis inherit Call to Power II’s blend of politics, weapons, and AI.

-

Bridge to Indie and Modding Community:

- The 2020 AUTOcracy student project—a stealth game about a banished citizen hacking a museum—ironically continues the theme. It retains the dystopian setting, robot guards, and translocation mechanics, re-imagining autocracy as resistance.

- The shader and material techniques in Substance Designer used by the AUTOcracy team (Louis Stelfox, Anthony Motto) owe a debt to the SCUMM-era paint realism of the Settlers and SimCity art teams.

-

Influence on Dynamite Publishing and Specialist DCC:

- The approach of curating foundational games for new players influenced later bundles: The Sims 2 Ultimate Collection, Must-Play Strategy Games (2024), and Classics of Simulation (2025).

A Note on the Note: The Shadow Empire Calls It

The 2025 Shadow Empire: Republica DLC—with its Martial Law, Virtus, and External Crusades—feels like a spiritual successor in theme. The Matrix Games moodboard (2025) mirrors Call to Power II’s coup narrative. The Mark Parichy Inc. and Anno 2070-inspired city-builds are direct descendants of the bundled games.

Conclusion

Autocracy is not a game. It is a movement. It is a retrospective exhibit, a throwback to a time when simulation was magic, and when a ruler could shape an entire world with the click of a mouse. It is a bundle of legacy, faithfully reproducing titles that, in 2002, were already considered classics.

To reduce it to “just a compilation” is to miss the curatorial intention—to package the pillars of a genre in a single box, to frame them as a cohesive ideology: that of the player-king, the player-technocrat, the player-dictator.

The flaws—no unified menu, no modernization, no patching—are technical, not conceptual. They are the limitations of 2002, not design failures.

In 2025, as we play Cities: Skylines 2, Dawn of Man 2, and Unturned—games that are directly built upon the ideas in Autocracy—we owe this quiet release a debt. It preserved the soul of simulation gaming at a crucial moment.

It is not the greatest simulation game ever made. But it is one of the most important.

Final Verdict: Autocracy is a then-dirty, now-a-masterpiece-of-curation, a museum in a box. It deserves to be celebrated not as a game, but as a cultural document—a testament to the power of revision, preservation, and the enduring illusion of control.

9.2/10 — A Simulated Autocolectape of Excellence.