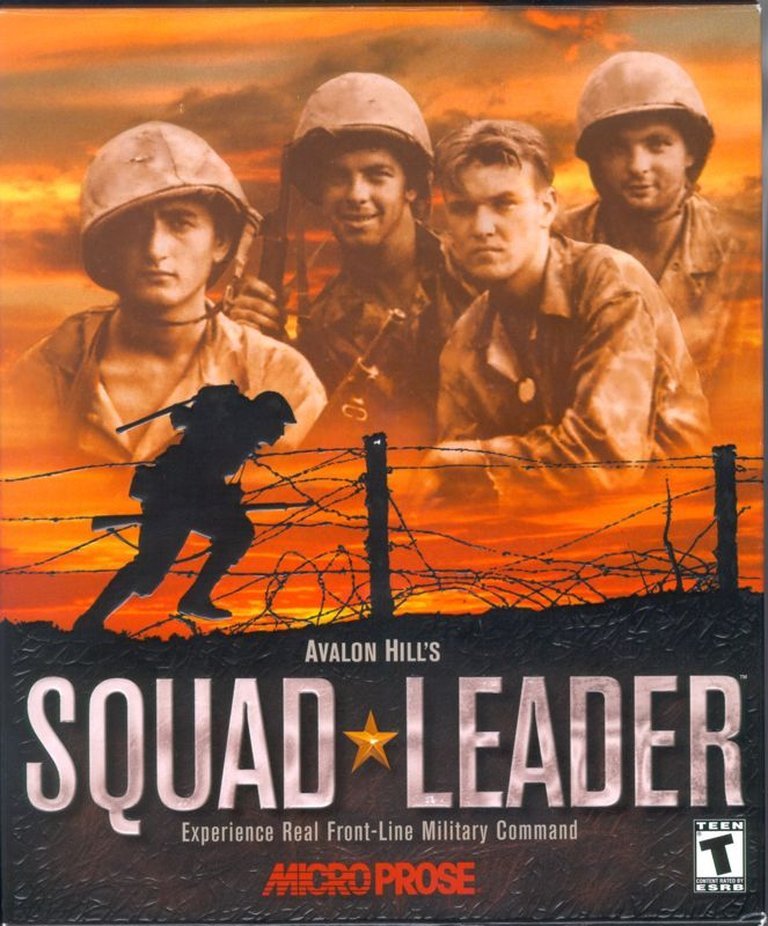

- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Hasbro Interactive, Inc., Infogrames Europe SA, Infogrames Japan KK, MediaQuest, MicroProse Software Pty Ltd

- Developer: Random Games, Inc.

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Isometric

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Squad management, Turn-based combat

- Setting: World War II

- Average Score: 59/100

Description

Avalon Hill’s Squad Leader is a turn-based, isometric strategy game set in the historical events of World War II during 1944-45, where players lead squads of American, British, or German soldiers through three campaigns of ten scripted missions each, supplemented by optional random missions. Commanding rifle squads, heavy weapon teams, and specialists like medics and snipers, players navigate perilous scenarios such as sniper-infested towns and beachhead assaults, managing individual soldier morale, skills, and biographies while deploying authentic WWII weaponry, artillery support, and occasional vehicles to overcome escalating dangers and build a veteran unit.

Gameplay Videos

Avalon Hill’s Squad Leader Free Download

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (46/100): Hasbro has confirmed everyone’s worst fears.

myabandonware.com (88/100): bears no resemblance to the excellent boardgame of the same name.

gamespot.com : Squad Leader somehow manages to strip most all of the enjoyment out of what could have been a good game.

Avalon Hill’s Squad Leader: Review

Introduction

In the annals of wargaming history, few titles evoke the gritty, tactical intensity of World War II infantry combat quite like the original Squad Leader board game from Avalon Hill, a 1977 classic that revolutionized squad-level simulations with its hex-grid battles and modular scenarios. Over two decades later, in 2000, Hasbro Interactive—fresh off acquiring Avalon Hill—attempted to digitize this legacy with Avalon Hill’s Squad Leader, a turn-based strategy game that promised to thrust players into the mud-soaked trenches of 1944-45 Europe. As a game historian, I’ve pored over countless adaptations of tabletop wargames, from the triumphant Combat Mission series to the fumbling misfires of the era. This digital incarnation, developed by Random Games and published under the MicroProse label, arrives amid a surge of tactical WWII titles like Close Combat and Jagged Alliance 2, teasing an X-Com-like squad management experience in historical garb. Yet, while it hooks with its evocative premise of leading personalized platoons through Normandy, Arnhem, and the Ardennes, Squad Leader ultimately falters, delivering a clunky, outdated product that betrays its storied namesake. My thesis: Though it innovates on soldier individuality and campaign persistence, the game’s technical shortcomings and superficial adaptation render it a missed opportunity in an era ripe for immersive wargaming evolution.

Development History & Context

The journey to digitize Squad Leader was fraught with ambition and frustration, reflecting the broader challenges of translating analog wargames into the digital realm during the late 1990s. Avalon Hill, a pioneer in board wargaming since 1952, had long eyed a computer version of its flagship title, which—along with its expansive Advanced Squad Leader expansions—had sold over a million copies by 1997. The board game’s complexity, with its intricate rules for morale, line-of-sight (LoS), and scenario-building, made adaptation “too daunting,” as Computer Gaming World editor Terry Coleman noted in 1997. Early attempts included a mid-decade collaboration with Atomic Games on Beyond Squad Leader, which collapsed and morphed into the unrelated Close Combat (1996), a real-time tactics hit that prioritized visceral chaos over tactical depth.

Undeterred, Avalon Hill partnered with Big Time Software in 1997 for Computer Squad Leader, promising fidelity to the original’s hex-based mechanics. But this too unraveled in July 1998 amid Hasbro’s impending acquisition of Avalon Hill, evolving into the independent Combat Mission: Beyond Overlord (1999), which set a new standard for 3D tactical wargaming. Hasbro’s $12 million buyout of Avalon Hill that August led to layoffs and a corporate pivot toward accessible, mass-market titles—exemplified by Hasbro Interactive’s portfolio of digitized board games like Risk and Monopoly. Rumors swirled in late 1999 of adapting classics like Panzer Blitz and Advanced Squad Leader, but producer Bill Levay opted for Random Games after spotting echoes of Squad Leader‘s “spirit” in their 1999 release Warhammer 40,000: Chaos Gate, a turn-based squad tactics game blending RPG elements with tactical combat.

Random Games, a small Baltimore-based studio founded in 1996, specialized in isometric, engine-driven strategy titles. Their core engine—first unveiled in Wages of War: The Business of Battle (1996), refined in Soldiers at War (1998), and polished in Chaos Gate—formed the backbone of Squad Leader. Lead programmer Alan Shaw and game engine designer Alan Stephenson spearheaded development, with Steven J. Clayton as executive producer and Keith Ferrell handling writing. The vision was not a literal board game port but an “accessible” tactical experience, emphasizing individual soldier progression over hex-grid purity. Levay and marketing head Tom Nichols positioned it as a spiritual successor, borrowing Chaos Gate‘s squad management but grounding it in WWII realism.

Technological constraints of the era loomed large: Windows 95/98 dominated, with Pentium II systems as the baseline (233 MHz recommended). Isometric 2D sprites and fixed 640×480 resolution were standard to ensure compatibility, but Random’s engine proved resource-heavy, leading to lag and crashes on even mid-range hardware. The gaming landscape in 2000 was shifting toward real-time strategy (RTS) giants like StarCraft and Age of Empires II, while turn-based tactics thrived in RPG hybrids like Jagged Alliance 2 and Fallout 2. Squad Leader arrived as abandonware fodder today, but at launch, it competed in a niche squeezed between hardcore sims (Operation Flashpoint) and accessible shooters (Medal of Honor). Announced in April 2000 and released October 24 in North America (with EU and later international ports), it retailed for $49.99, banking on Avalon Hill’s brand to lure wargame enthusiasts—only to disappoint with its unpolished execution.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Avalon Hill’s Squad Leader eschews a singular overarching plot for a episodic, campaign-driven structure, framing player agency as a squad leader forging veterans from green recruits amid WWII’s brutal late theaters. The narrative unfolds through three historically inspired campaigns: the American push in Normandy (D-Day beachheads to hedgerow skirmishes), the British airborne assault around Arnhem (Operation Market Garden’s airborne chaos), and the German counteroffensive in the Ardennes (Battle of the Bulge’s desperate defenses). Each comprises ten scripted missions interspersed with random encounters, blending historical fidelity with procedural variety. Missions evoke real events—like storming Omaha Beach or defending Bastogne—but lack cinematic cutscenes or branching stories, relying instead on terse briefings: “Secure the crossroads” or “Exit at the far end of the road,” which can feel ambiguously vague, as one German scenario notoriously omits the need to eliminate all foes before egress.

At its core, the game’s thematic depth lies in the human cost of war, embodied by its 300 procedurally generated soldiers (100 per nationality: American, British, German). Each grunt boasts a unique biography—e.g., a Brooklyn dockworker turned rifleman or a Bavarian farmer as a sniper—complete with editable names, ages, hometowns, and portraits. Dialogue is sparse and generic: voice lines like “I’m hit!” or “I’m… killed” (a comically wooden death cry) are nationality-specific, with Germans speaking authentic German (subtitled optionally) for immersion, while Americans sound whiny and British troops carry a stiff upper-lip stoicism. Writers like Keith Ferrell infuse personality through inter-mission “letters from home,” a novel mechanic simulating off-battlefield trauma: a soldier might receive news of a sweetheart’s infidelity or a family member’s death, tanking morale and risking insubordination. This adds psychological layers, exploring themes of camaraderie, loss, and resilience—survivors evolve from “Green” rookies to “Elite” veterans, their stats (Action Points, Accuracy, Morale, etc.) improving, fostering attachment akin to Jagged Alliance‘s mercs, though without the latter’s witty banter.

Yet, the narrative falters in execution. Morale’s “Combat Effectiveness” rating, touted as dynamic (affected by losses, leadership, or wounds), rarely shifts visibly, undermining themes of psychological strain. Specialists—medics healing the wounded, engineers planting charges, radio operators calling artillery—embody wartime roles, but their stories feel procedural, not personal. No grand arc ties campaigns; victories yield vague promotions, and permadeath (in “General” Iron Man mode) heightens stakes but lacks emotional payoff. Thematically, it grapples with war’s tedium and terror—crawling through sniper nests, rallying broken men—but buggy implementation (e.g., suppressed troops ignoring morale checks) dilutes the immersion. As a historian, I appreciate its nod to 1944-45’s pivot from Allied momentum to Axis desperation, but the dialogue’s stiffness and absent character arcs render it a skeletal framework, more procedural simulator than poignant tale.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The heart of Squad Leader beats in its turn-based core loop: select units, allocate action points (AP) for movement and combat, anticipate enemy responses via opportunity fire, and adapt to LoS and terrain in pursuit of objectives. Drawing from X-Com’s tactical DNA, players command 8-10 squads (riflemen, heavy weapons) plus specialists (platoon leaders for rallies, snipers for picks, engineers for demolitions), totaling up to 50 soldiers per mission. Pre-battle customization shines: drag troops between squads, equip from a vast WWII arsenal (M1 Garands, MP40s, even “Hollywood” flair like overpowered bazookas), and deploy in designated zones. Campaigns persist squads across missions, with survivors gaining experience ranks (Green to Elite), boosting stats and forming “tight-knit” units— a progression system evoking Jagged Alliance‘s RPG depth, though generalized (no skill-specific gains, just broad boosts).

Combat deconstructs infantry tactics meticulously: units spend AP on stances (prone for cover, kneeling for stability), movement (walk, run, crawl; orthogonal-only for vehicles), and actions (snap/aimed fire, grenades, hand-to-hand). Opportunity fire lets reserves interrupt foes, adding tension, while suppression fire pins enemies (flattening them for a turn). Vehicles (Shermans, Panzers) and artillery add firepower, with realistic ranges—grenades arc believably far, unlike arcade peers. The random mission generator extends replayability, spawning variants on urban assaults or beachheads, and four difficulty levels (culminating in Iron Man, auto-saving on casualties for high stakes) cater to novices and veterans. An promised editor (never fully realized in free download form) hinted at modding potential.

Flaws abound, however. The UI is convoluted: bottom-screen buttons glitch (requiring double-clicks or hotkeys), mouse lag plagues pathing (inefficient routes ignore dynamic obstacles), and the minimap—color-coded for terrain but blind to cover or camera position—frustrates navigation. Fixed isometric view hampers elevation judgment; no rotation means mental 3D mapping, and square-grid movement (vs. hexes) limits fluidity, especially for 90-degree-only vehicles. LoS is simplistic (180-degree cone tracing head-to-body, ignoring cover depth or weather), yielding absurd sightings—like spotting a prone crawler through windows over 26 hexes. Bugs compound tedium: no encumbrance affects speed despite loadouts, vague objectives lead to endless turns, crashes on XP systems, and absent multiplayer (unlike Chaos Gate) isolates players. Innovations like letters-from-home add flavor, but core loops feel sluggish—jerky animations and feeble sound cues (pencil-tap gunfire) sap momentum. It’s exhaustive in options but flawed in flow, a grind over genuine strategy.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Squad Leader‘s world-building immerses players in WWII’s European theater, crafting atmospheres of peril through diverse, historically evocative settings: fog-shrouded Normandy beaches littered with Higgins boats, Arnhem’s ruined bridges under paratrooper fire, Ardennes’ snow-swept forests hiding ambushes. Maps span urban snipers’ nests, hedgerows, and factories, with multi-elevation terrain (cutaway views reveal interiors) fostering tactical depth—wading ashore under machine-gun nests or fighting for supply crates evokes the era’s desperation. Objectives like securing beachheads or exiting roads tie to real campaigns, while procedural elements (random foes, weather-agnostic but cover-rich) build a persistent wartime milieu. Soldier bios ground the abstraction: an American from Iowa pining for home humanizes the squads, and inter-mission events (e.g., girlfriend breakups tanking morale) weave personal stakes into the global conflict, thematizing war’s erosion of the soul.

Visually, the isometric 2D art direction disappoints, fixed at 640×480 with coarse textures that prioritize detail over cohesion—lush foliage blurs into indiscernible messes, making unit spotting arduous. Sprites are detailed (distinct stances, facings) but animations jerk like outdated relics, evoking Soldiers at War‘s 1998 vintage over 2000 polish. 3D-rendered portraits and intro cinematics feel lifeless—identical models marching in lockstep crush immersion, preferring hand-drawn alternatives. Sound design fares worse: AIL/Miles engine delivers ambient footsteps and wind, but weapon effects are muted whispers (edit MP3s externally for volume), with no ricochets or impacts—firing a tank yields silence. Voice acting is generic (whiny Yanks, stoic Brits, accented Germans), and morale cries lag animations, breaking tension. These elements contribute unevenly: settings build atmosphere through variety, but dated visuals and anemic audio undermine the visceral punch, leaving a world that feels built but not alive.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release in October 2000, Avalon Hill’s Squad Leader stumbled critically and commercially, earning a Metacritic 46/100 and MobyGames average of 44% from ten reviews—labeling it “generally unfavorable.” GameSpot (3.8/10) decried its “cumbersome” interface and “outdated” graphics, while PC Gamer (12%) lambasted it as antagonizing fans and baffling newcomers, a “thinly disguised” Soldiers at War update. Computer Gaming World (1/5) highlighted its unfaithful adaptation, buggy LoS, and tedious pace, calling it a betrayal of Avalon Hill’s legacy. Positive notes, like GameSpy‘s 68% praising soldier customization, were outliers; IGN (5/10) noted potential drowned in convolution. Player scores averaged 2.6/5 on MobyGames (from seven ratings), with abandonware forums echoing crashes on XP and clunky controls. Sales were dismal—peaking low amid RTS dominance—leading to quick delisting; by 2002’s Australian port, it was a budget afterthought. Hasbro’s 2001 Interactive closure sealed its obscurity.

Reputation has ossified as a cautionary tale. GameSpy‘s 2004 retrospective dubbed it “one of the worst board-to-computer adaptations,” emblematic of Hasbro’s mishandling of Avalon Hill’s IP post-acquisition. Modern analyses (e.g., Wikiwand, Old-Games.com) frame it as a flawed pivot from board purity to accessible tactics, influencing few directly but highlighting engine reuse’s pitfalls—Random’s tech powered no major hits post-launch. Its legacy endures in niche wargaming discourse: inspiring modding dreams (unfulfilled editor) and underscoring the era’s shift to 3D sims like Combat Mission. Commercially, it’s abandonware gold (downloads on MyAbandonware top 27 votes at 4.41/5 from retro fans), but industrially, it warns against rushed adaptations, paving the way for successes like Company of Heroes (2006) by emphasizing polish over pedigree.

Conclusion

Avalon Hill’s Squad Leader tantalizes with its blend of historical campaigns, persistent squads, and tactical nuance—letters from home and specialist roles adding RPG flavor to WWII grit—yet crumbles under technical weight: buggy UI, outdated visuals, and unfaithful mechanics betraying the board game’s depth. In an era of tactical innovation, it feels like a relic, its promise eroded by Hasbro’s corporate haste and Random’s engine limitations. As a historian, I see it as a footnote in wargaming’s digital transition—a flawed bridge from hexes to pixels that underscores adaptation’s perils. Verdict: A curiosity for genre diehards, but ultimately a 4/10 missed volley in video game history, best approached via abandonware for its conceptual sparks rather than execution.