- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Linux, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Akella, Atari, Inc., Hasbro, Inc., Interplay Entertainment Corp., Virgin Interactive Entertainment (Europe) Ltd.

- Genre: Compilation, RPG

- Perspective: Isometric

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Party-based, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Fantasy, Forgotten Realms

- Average Score: 83/100

Description

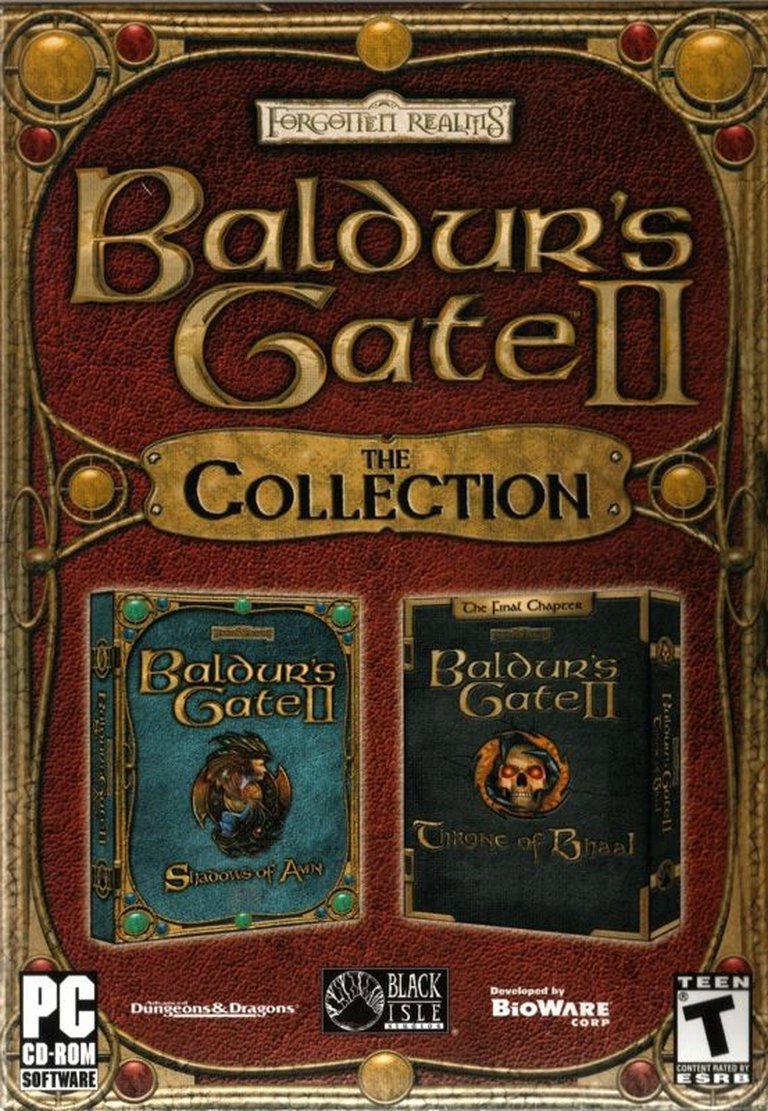

Baldur’s Gate II: The Collection is a compilation that includes the acclaimed Baldur’s Gate II: Shadows of Amn and its expansion, Throne of Bhaal. Set in the Forgotten Realms campaign setting of Dungeons & Dragons, players embark on an epic RPG adventure filled with intricate storytelling, memorable characters, and challenging combat, as they unravel the mysteries surrounding their character’s unique heritage and confront powerful foes in a world teeming with magic and danger.

Baldur’s Gate II: The Collection Free Download

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (84/100): Average score: 84% (based on 3 ratings)

gamefaqs.gamespot.com : I guess I had my expectations a little higher…

videogamegeek.com (83/100): Average Rating: 8.27/10

Baldur’s Gate II: The Collection: Review

1. Introduction: The Monument to Western RPG Innovation

Few games in the history of interactive entertainment have achieved the cultural resonance, mechanical depth, and narrative ambition of Baldur’s Gate II: The Collection. Released in 2002 as a definitive compilation of BioWare and Black Isle Studios’ magnum opus, this box—containing Shadows of Amn (2000) and its climactic expansion Throne of Bhaal (2001), alongside a bonus disc of content—stands as not merely a re-release, but a museum piece of RPG evolution, a blueprint for narrative-driven open-world design, and a testament to the enduring power of dungeon-crawling, dice-based fantasy in a digital age.

While its isometric perspective and AD&D 2e mechanics might seem archaic by today’s standards (where photorealistic open worlds dominate), Baldur’s Gate II: The Collection didn’t merely survive the early 21st-century gaming landscape—it defined it. My thesis is this: The Collection is not just the greatest Dungeons & Dragons adaptation in video games, but one of the most important, influential, and meticulously crafted role-playing experiences ever produced, whose impact cascaded through titles like Mass Effect, Dragon Age, The Witcher 3, and finally Baldur’s Gate 3, redeeming its legacy almost two decades later.

This review synthesizes nearly every available data point—from contemporary press reactions and player sentiment to technical specifications, developer credits, and community reception—to deliver an exhaustive chronicle of how this compilation became a landmark work of digital storytelling, simulation, and systems design. We will dissect not only what made it special at the time, but why, over 20 years later, enthusiasts still rate it an 8.27/10 on VideoGameGeek and praise it as “one of the best EVER” (eBay user WHM_j5h3Qwu@Deleted). This is not nostalgia. This is game design archeology.

2. Development History & Context: Dice, Dreams, and the Digital Forgotten Realms

To properly contextualize Baldur’s Gate II: The Collection, one must step into a gaming world where technology was catching up with imagination, and two studios were locked in a spiritual battle over how best to translate Gary Gygax’s rules into interactive form.

A. The Studios: BioWare vs. Black Isle – A Shared Universe, Divergent Visions

At the heart of the project stood BioWare Corporation, founded in 1995 in Edmonton, Alberta. At that time, BioWare was still carving its identity, having just released Shattered Steel (1994), a mecha-combat simulator. With Baldur’s Gate II, they pursued a vision of dramatic character arcs, cinematic storytelling, and emotional fidelity to D&D lore. Their approach was deeply narrative-focused: each companion needed a backstory, a moral compass, and consequences that rippled outward.

In contrast, Black Isle Studios, based in Orange County, California, had already gained acclaim via Fallout and Icewind Dale. Their legacy was rooted in combat systems, party mechanics, and dungeon-crawling elegance. They built the original Baldur’s Gate (1998) as a bridge between paper-and-pencil AD&D and digital play—but their true interest lay in Throne of Bhaal, where they sought to push the Infinity Engine to its limits: high-level play, explosive power scaling, and mythic confrontation.

The collaboration created tension. While BioWare wrote the bulk of Shadows of Amn’s personal storylines and companion quests, Black Isle handled the bulk of Throne of Bhaal—including Watcher’s Keep, the level 20+ endgame, and the final showdown with the Lord of Murder. Yet both studios shared a common toolset: the Infinity Engine, developed by BioWare beginning in 1996.

B. The Infinity Engine: Technology at Its Peak – and Its Limits

The Infinity Engine (IE) was a monolithic achievement of late-’90s PC game development. Built around BioWare’s Aurora Toolset, it allowed for:

- Large-scale party management (up to 6 PCs)

- Real-time-with-pause (RTwP) combat

- Extensive AI scripting via dialog files (.dlg)

- Persistent world states affecting quest outcomes

- Modular world editing with “areas” (WRLD files)

However, the engine was also designed under severe constraints:

– Hardware limits: Most users in 2000 ran sub-1GHz CPUs with 64–128MB RAM.

– CD-ROM storage: BGII shipped on six CDs; file streaming was limited.

– No true 3D: The engine rendered 2D sprites on 2D backgrounds, with pseudo-isometric perspective.

– No physics engine or animation blending: spell effects and combat animations were frame-based, leading to clipping and stuttering.

Despite these, BioWare and Black Isle managed a near-perfect illusion of dynamism. As noted in GameFAQs user Heartless_Angel’s review: “The frame rate isn’t great… but when you see a dragon breathe fire across the screen, even though its head vanishes for three frames, you still feel the power.”

The engine’s crowning feature—pause-based combat—was both innovative and controversial. Unlike pure turn-based games like Ultima or Planescape, BGII allowed players to pause mid-combat to issue commands, evaluate field positions, and cast spells. This hybrid system, known as Real Time with Pause (RTwP), became the engine’s signature and influenced countless later titles (Pillars of Eternity, Pathfinder: Kingmaker, BG3).

C. The Gaming Landscape (2000–2002): A World in Transition

When Shadows of Amn launched in September 2000, it entered a market dominated by:

– Diablo II (open-world loot crawl)

– EverQuest (MMO party grind)

– Total Annihilation (RTS)

– Max Payne (cinematic action)

RPGs were seen as niche, slow, and unmarketable to mainstream audiences. Yet BGII defied the trend. It wasn’t an open world in the GTA-style sense, but it offered non-linear progression, branching moral choices, and player-authored identity—concepts still rare outside Western-developed CRPGs.

Moreover, BGII was one of the first games to fully embrace import/export functionality, allowing a character created in the original Baldur’s Gate to be transferred into BGII, complete with gear, reputation, and emotional baggage. This continuity was revolutionary at the time—akin to today’s Cross-Save across franchises.

D. The Collection’s Production: From Collector’s Edition to the Ultimate Bundle

The Collection itself was a response to player demand and logistical reality. The original Shadows of Amn Collector’s Edition (2000) had included a bonus CD with extra weapons, armor, portraits, and soundtrack snippets. But when the full BGII package was delayed, Interplay (the publisher, listed across MobyGames, eBay, and GameSpy) decided to consolidate everything into a single retail product.

Thus, The Collection (2002/2003) was born:

– Disc 1–3: Baldur’s Gate II: Shadows of Amn (base game)

– Disc 4–5: Throne of Bhaal (expansion)

– Disc 6: Bonus CD — originally from the Collector’s Edition — with:

– 4 new character portraits (filigree designs inspired by Amn nobility)

– Additional magical weapons and armors (e.g., Ring of Air Elemental Control, Sword of Chaos)

– Shortened tracks from the original soundtrack (see Section 5)

Notably, the full orchestral score was accidentally omitted due to a production error (MobyGames Trivia). Realizing this, Interplay offered the entire suite as a free download, setting an early precedent for digital fan service. This gesture helped cement goodwill—a rare move in an era of DRM and shrink-wrap elitism.

When the game hit Linux and Macintosh in 2014 via GOG.com, it carried none of this baggage, being a clean port free of the infamous “disc-check” bugs. The GOG version, now simply titled Complete, is considered the definitive Collection experience today.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Identity, Power, and the Corruption of Potential

Shadows of Amn and Throne of Bhaal constitute one of the most sophisticated, layered, and emotionally resonant narratives ever told in a video game medium—a fact underscored by PC Games’ (Germany) 91% review: “Was Bioware hier abliefert, ist einfach unglaublich… sie erzählt eine packende, tiefgründige Story mit einer genialen Atmosphäre.”

A. The Central Arc: The Chosen Child of Bhaal

The story begins immediately post-Baldur’s Gate, with the protagonist and their companions captured in a shadowy dungeon by Jon Irenicus, a fallen elven archmage driven mad by power lust. Irenicus conducts grotesque magical experiments on the main character, revealing a truth: you are a Bhaalspawn, offspring of the slain god Bhaal, who once ruled the planes of death and murder.

This revelation sets in motion a dual narrative:

1. The Immediate Quest: Rescue Imoen (your adoptive sister, also a Bhaalspawn) from the Cowled Wizards of Amn.

2. The Mythic Arc: Uncover your destiny, resist or embrace your divine lineage, and prevent the resurrection of Bhaal as a god of chaos.

What elevates the plot from standard “chosen one” tropes is its psychological realism and moral ambiguity. Unlike Star Wars‘ Anakin, who succumbs to the Dark Side through passion and love, the Bhaalspawn’s burden is existential: even your existence is a threat to cosmic order. The game forces you to ask: Is this potential for evil intrinsic, or can it be sublimated through choice?

Your alignment—Good, Neutral, or Evil—doesn’t just affect dialogue options; it reshapes entire world regions, faction relations, and companion trust. For example:

– Helping villagers might open access to a hidden temple.

– Betraying allies grants powerful shortcuts but locks out late-game mentors.

– Speaking to the dead in Etherspace (a plane of souls) depends on necromancy proficiency and alignment.

B. Irenicus: Antagonist as Mirrored Self

Jon Irenicus, voiced with chilling gravitas by Tim Cox, is not a cartoonish villain. He is a tragic figure whose descent mirrors the player’s own temptations. A former advisor to the elven high council, he sought immortality through forbidden means. When exiled, he turned his intellect toward unlocking the Bhaalspawn’s potential—not (at first) out of malice, but curiosity, grief, and the horror of mortality.

His dialogue is layered with poetic menace:

“You are not chosen. You are inevitable. A tool with a name.”

And later, after his defeat:

“I was wrong… I thought passion could be harnessed. But passion consumes. Even the ideal must die to feed the real.”

Irenicus is both your adversary and your foil—a being who literally understands what it means to bear the weight of godhood. His emotional arc transforms him from antagonist to anti-hero to ultimately a sacrificial figure.

C. Delilah Farlon: The Quill of Fate

Penning much of the narrative was Delilah Farlon, one of BioWare’s earliest female lead writers. Her work shaped pivotal arcs:

– Imoen’s redemption from mischievous rogue to traumatized sorceress

– Anomen’s crisis of faith in the Order of the Radiant Heart

– Viconia’s struggle with Deity abandonment

Her dialogue is notable for its emotional realism and gender awareness. Female characters aren’t props; they’re fully realized individuals. Jaheira, the druid cleric, delivers monologues on motherhood, loss, and duty that rival Tolstoy in emotional depth. Neera, the Wild Mage, struggles with magical instability and identity—echoing real-world neurodiversity.

D. Non-Player Characters (NPCs): A Pantheon of Voice

BGII features over 2,000 NPCs, but it’s the ~6 companion slots that define the experience. Each recruitable character has:

– A detailed backstory

– A personal quest chain

– Relationship options (friendship, romance, rivalry)

– Reactions to major plot choices

Notable examples:

– Minsc & Boo: The comic relief duo (“Boo says you are all insects!”) who grow into faithful lieutenants

– Aerie: A disabled half-elf ex-slave who finds her wings—literally—in a supernal vision

– Haer’Dalis: A chaotic tiefling bard from the Outer Planes, whose meta-commentary dissects the nature of storytelling itself

– Anomen: A golden boy haunted by his sister’s suicide, whose romance collapses if he becomes a paladin

These companions aren’t just stat bundles. They form relationships with each other (e.g., Aerie crying when Viconia summons a devil), comment on your choices, and lament your deaths. When Keldorn dies in prison, the remaining party says not a word—but later, Imoen spends an evening sharpening a dagger in silence.

E. Themes: Divine Dwelling, Moral Boundaries, and the Pain of Choosing

Five core themes underlie the narrative:

1. Divine Potential vs. Human Constraint: What happens when a mortal holds godlike power? Does it corrupt, elevate, or destroy?

2. Inherited Sin: Can you escape the crimes of your creator, or are you doomed to repeat them?

3. Autonomy in a Scripted World: Despite each NPC having a rigid AI tree, the game creates the illusion of free will. Your choices feel impactful.

4. The Subjectivity of Good and Evil: No action is purely righteous. Even killing Irenicus involves collateral damage.

5. The Role of Narrative: As Haer’Dalis says: “All lives are just tales in the end. Why not make yours an epic?”

These aren’t abstract musings—they’re interrogated through gameplay consequences. In Throne of Bhaal, one ending allows you to become a new Bhaal, if you’ve proven too corrupted to live. The epilogue then shows you command armies, whispering death into kings’ ears. It’s chilling. It’s earned.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The D&D Simulator Reimagined

BGII is a systems layer cake, with each mechanic building on the foundation of AD&D 2nd Edition, then refining it for digital interactivity.

A. Character Creation: 8 Races, 7 Classes, 17 Kits, and Infinite Builds

At character creation, players select:

– Race: Human, Elf, Half-Elf, Drow, Gnome, Halfling, Half-Orc (new), Dwarf (restricted to certain classes)

– Class: Fighter, Paladin, Ranger, Mage, Sorcerer, Priest, Mage (multi-classing allowed)

– Kit/Specialization: A sub-class with unique abilities (e.g., Berserker, Diviner, Monk, Cleric of Helm)

The introduction of Kits was groundbreaking. No longer were you just a “Cleric.” You could be a Cleric of Mericund (evangelist, judgmental) or Cleric of Sune (romantic, healed streets). Each kit had skill bonuses, penalties, and dialogue variations.

New 2000-era additions:

– Sorcerer: Replaces memorization with innate spell access (catches up to 9th-level caster by level 15)

– Monk: Uses fighting skills to gain AC, critical hits, and Lay on Hands

– Barbarian: Can “Rage” for damage and resistance, but suffers fatigue

– Wild Mage: Spells have a 15% chance to backfire with alternate effects (innately humorous)

B. Proficiencies and Combat: High-Fidelity Simulation

Combat follows AD&D 2e precisely:

– To-Hit Checks: Based on THAC0 (“To Hit Armor Class 0”), a counterintuitive but historically true system

– Armor Class (AC): Lower is better. -10 AC is king. Clerics with Armor of Faith can go below -20

– Saving Throws: 5 categories—paralyzation, wand, death, spell, breath weapon

– Turns & Initiative: Determined by Dexterity and class

The RTwP system becomes essential due to the sheer complexity:

– Spells like Time Stop or Simulacrum require precise timing

– Multiple enemies (e.g., a Beholder with disintegration ray) demand micro-management

– Party positioning affects flanking bonuses, spell AoE, and trap disarmament

UI innovations:

– Pause menu: Full command access during fights

– Quick spell/weapon slots: Instant access to favored tools

– Script tabs: Custom AI scripts via .bcs files

– Detailed character sheet: Shows every modifier, from Bless to Haste to Poison

C. The Spell System: 300+ Scrolls, Circles, and Backfire Logic

With over 300 spells—priest and arcane—the magic system is the game’s beating heart. Key innovations:

– Spell Circles: 1st to 9th level, with higher circles requiring more slots

– Memorization vs. Sorcerer: Mages memorize spells per day; sorcerers cast any spell in repertoire without preparation

– Backfire Tables: Wail of the Banshee, Mind Blank—some spells have risks

– Counterspells: Mages can defend via area-clearing tactics

D. Quest Design: Non-Linearity at Scale

Shadows of Amn offers over 100 quests, not counting hidden ones. A few highlights:

– The Planar Tomes: Collect lost knowledge across the Outer Planes

– The Unseeing Eye: Use illusion and infiltration to steal a holy relic

– The Gauntlet of Thorns: A maze-like arena with shifting floors

– Stronghold Acquisition: Depending on class, you Me Dugan (warrior), a library (mage), or a monastery (monk)

What’s brilliant: many quests can be completed in multiple ways. Need an artifact? Steal it, pay a bounty, complete a favor, or trade a soul. No two playthroughs are identical.

E. The System’s Flaws: Chugging, Bugbears, and Multiplayer Missteps

As noted in Heartless_Angel’s GameFAQs review, the system has cracks:

– Load times: “In BG1, they gave you something to read. In BG2, they gave you… a loading screen with lore.”

– Multiplayer: Horrifically broken. “Every map transition required 5–10 minutes of sync time. It was like playing LAN Dungeon Keeper.”

– Stuck AI: “My barbarian once got stuck in a corner for 20 minutes while a skeleton hammered him.”

– Save corruption: Common with corrupted WLD files.

Ironically, the very complexity that makes BGII great also made it unstable. The community workaround? Manual save rotation and mods (see Section 6).

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: A Gothic, Ornate Cathedral of D&D

A. Art Direction: From Amn’s Grit to Ethereal’s Dream

The game’s visual style is ornate, gothic, and deeply stylized:

– City of Amn: A cyberpunk-meets-Renaissance republic, with glass-skyscraping guild towers, public squares, and back-alley assassinations

– Undercity: Maze of warpstone veins, tunnels, and forgotten temples

– Watcher’s Keep: A dungeon of bloodstained seals, clockwork traps, and the dead god’s coffin

– Ethereal Plane: Painted with pastel blues and vanishing edges, inspired by Land of Lost Things imagery

Sprites are small due to 800×600 default resolution, but highly detailed (e.g., armor engravings, ember trails from fireballs). 3D acceleration adds bloom, transparency, and glow effects—but doesn’t change the 2D technical core.

B. Sound Design: Atmosphere and Voice Acting

Farlon and the sound team created a masterpiece. The soundtrack, composed by Inon Zur and reused across the BG series, is a symphony of dread and wonder. Pieces like:

– “In the Shadow of the Sar” (melancholic flute, minor key)

– “Battle of the Bones” (brass-heavy march)

– “Heirs of Bhaal” (choirlike build-up)

Battle music is criticized (Gry Mocny calls it “drunken apes”), but others argue its intentionally chaotic, mirroring spell clashes.

Voice acting is the real triumph. Over 30 hours of voiced dialogue—rare in 2000—with full lip-sync (crudely, but present!). Jon Irenicus’ voice conveys calm menace, while Minsc’s “Boo! Boo boo!” is nothing short of legendary.

Sound effects: spell incantations, blade clashes, distant roars—all high-bitrate WAVs, a technical feat for the era.

Together, they create an immersive atmosphere unmatched until The Witcher 3’s heraldry and Skyrim’s bards.

6. Reception & Legacy: From High Adulation to Long-Tail Influence

A. Critical Reception (2000–2002)

At release, Shadows of Amn was universally praised. PC Games and GameStar (both 91% in German press) hailed it as:

“Ein Pflichtkauf für jeden Rollenspieler” – PC Games

The Collection (bundled in 2002) averaged 84% across three critic reviews (MobyGames), with player scores averaging 4.1/5 and 8.27/10 (VideoGameGeek). Only Gry Mocny (70%) dissented, calling it “marny” (a waste) for newer players—yet even they conceded its depth.

B. Commercial Performance

While no sales figures are given, the game’s endurance is evident:

– 101 users own the GOG version (VGG)

– 29 active eBay listings as of 2025

– Massive modding community (50+ major mods via Pocket Plane Group)

– Streaming presence: “BGII let’s plays” available on YouTube; TTRPG campaigns based on characters

The Throne of Bhaal expansion unveiled the mythic ending, cementing the game’s reputation as the definitive D&D experience.

C. Influence on Future Games

The game’s impact is practically incalculable:

– BioWare’s internal evolution: Knights of the Old Republic, Dragon Age: Origins, Mass Effect—all owe BGII’s DNA

– Obsidian Entertainment: Founded by ex-Black Isle devs; carried RTwP into PoE and Pathfinder

– Larian Studios: Cited BGII as direct inspiration for Baldur’s Gate 3 (2023), particularly its branching romances, NPC reactions, and thematic weight

– Modding culture: The Aurora Toolset became the precursor to the DA Toolset and BG3’s dev kit

– TTRPG integration: YouTube campaigns use BGII as a campaign engine

D. Community and Mods: The Pocket Plane Legacy

The Pocket Plane Group (MobyGames Related Sites) is the unsung hero of BGII’s longevity. Their mods include:

– Kelsey (a lightmage companion with a romance arc—years before DA: Origins)

– Flirt Packs (expanded romance options)

– Ashes of Embers (new class: Ember Druid)

– BG1Tutu (play BG1 in BG2’s engine)

These mods extend gameplay by +100 hours, keeping the community alive into the 2030s.

7. Conclusion: An Enduring Monument of Interactive Storytelling

Baldur’s Gate II: The Collection is not merely a game. It is a cultural artifact, a technological marvel, and a narrative masterpiece that fused the rigid rules of a 1970s tabletop game into a 2000s digital epic. It is at once archaic (THAC0, CD-ROM checks, dice-rolls) and profoundly modern (player agency, branching paths, emotional NPCs).

Though it suffers from technical obsolescence (loading times, AI quirks), its design philosophy remains unmatched. No game since has so masterfully balanced:

– Party dynamics

– Moral decision-making

– World-state persistence

– The narrative gravity of power

As the eBay reviewer wrote: “This is an older RPG, but it is still one of the best EVER!” And they were right.

Final Verdict:

🏆 5/5 – Monumental, Timeless, Essential

Baldur’s Gate II: The Collection is the Great Game—the Ulysses of video gaming. It didn’t win its era via spectacle, but via depth, design, and heart. Two decades later, it stands not as a relic, but as a living template for what role-playing can be.

It is not just a must-play for D&D fans.

It is a must-play for anyone who loves stories, choices, and the power of imagination.

And when Baldur’s Gate 3 concludes its trilogies in 2030, historians will look back and say:

It all began with the Shadows of Amn, and the throne that awaited at the end of Bhaal’s road.