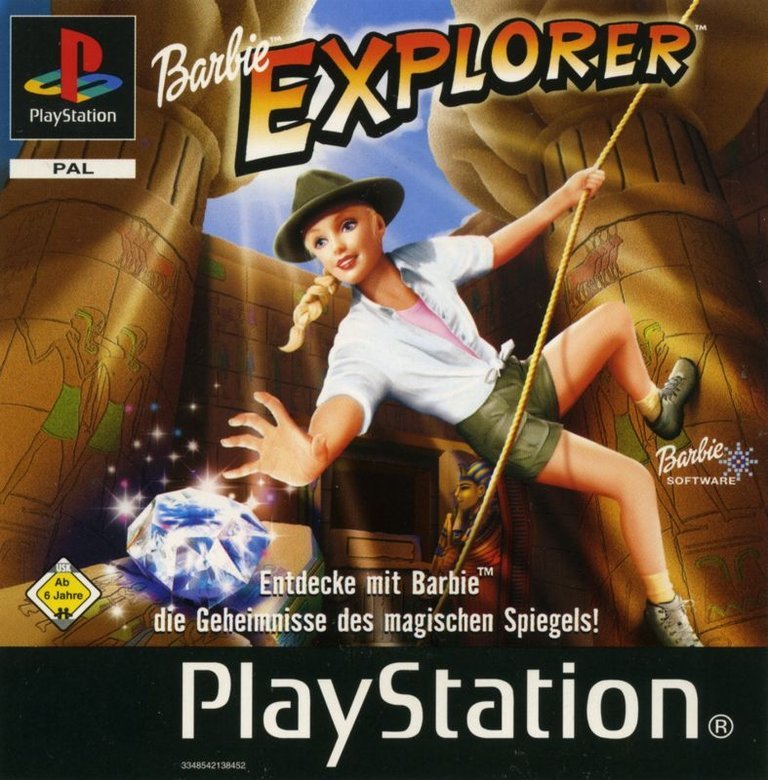

- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: PlayStation, Windows

- Publisher: Vivendi Universal Games, Inc.

- Developer: Runecraft Ltd.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Boss battles, Collectibles, Platform, Puzzle elements, Upgrades

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

Barbie Explorer is an action-platformer game inspired by the Tomb Raider series, where Barbie, a reporter, embarks on a global quest to find four missing shards of a mystical mirror that, if reassembled, will unleash great power. Players navigate diverse levels through jumping, climbing, and puzzle-solving, using collectible shoes like spring boots or hiking boots to gain new abilities, with each level ending in a boss fight for a shard. The game also includes a two-player mode where Barbie competes against Theresa to complete levels with the fewest lives and most gems.

Gameplay Videos

Barbie Explorer Free Download

Barbie Explorer Patches & Updates

Barbie Explorer Guides & Walkthroughs

Barbie Explorer Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org (80/100): a Tomb Raider-esque arcade adventure for young gamers

Barbie Explorer Cheats & Codes

PlayStation 1 (PS1)

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 8008db8a000f | Infinite Lives |

| 8008cd400064 | All Gems |

| 8009b6bebfff | Super Jump |

| 80160e3c0fa0 | Super Jump |

| 8009b6bebfef | Super Jump |

| 3008db630000 | Invincibility |

| 8008CD40 0064 | Have All Gems |

| 8008DB8A 0009 | Infinite Lives |

| 80036608 0001 | Extra Lives |

| 8003EF2C 00?? | Gems Worth Modifier |

| X + Triangle + Square | Extra Points |

| X + L1 + R2 | New Life |

| L1 + L2 + R2 | Power Up |

| X + R2 + Square | Level Jump |

| 8008DB8A 000F | Infinite Lives |

Barbie Explorer: Review

Introduction: A G-Rated Ghost in the Machine

In the crowded annals of early 2000s licensed video games, few titles simmer with the peculiar cultural and historical tension of Barbie Explorer. Released in September 2001 for the Sony PlayStation and later for Windows, this title from developer Runecraft represents a deliberate, if ultimately compromised, attempt to translate the burgeoning “action-adventure” genre—epitomized by Tomb Raider—into a safe, non-violent package for the Barbie demographic. It is a game caught between ambitions: aspiring to the globe-trotting, puzzle-solving prestige of Lara Croft’s exploits while being chained to the expectations of a doll franchise synonymous with fashion and fantasy, not perilous archaeology. This review will argue that Barbie Explorer is a fascinating, deeply flawed artifact. It is a testament to the era’s technological constraints, a case study in the difficulties of adapting mature gameplay mechanics for a younger, female audience, and a curious footnote that reveals as much about the video game industry’s anxieties regarding “girls’ games” as it does about its own modest design. Its legacy is not one of influence or acclaim, but of quiet, instructive failure—a ghost in the machine of both the platformer genre and the Barbie multimedia empire.

Development History & Context: The Runecraft Gambit

The Studio and the License:

Barbie Explorer was developed by Runecraft Ltd., a UK-based studio with a portfolio heavily weighted toward licensed family games and puzzle titles. Their previous work included games for Thomas the Tank Engine, Magic School Bus, and other Mattel properties like Barbie: Pet Rescue and Detective Barbie. This context is crucial; Runecraft was not an action-game specialist but a pragmatic workhorse for corporate licensors. The game was published by Vivendi Universal Interactive Publishing (under the Sierra Studios label in some regions) in partnership with Mattel Interactive, placing it within the late-era Vivendi Games stable before its eventual merger with Activision.

Technological and Design Constraints:

The game was built for the original PlayStation (PS1), a console whose 3D capabilities were being pushed to their absolute limit by 2001. While the PS2 had launched, the vast install base and lowerdevelopment costs kept the PS1 relevant, especially for budget and children’s titles. This meant Barbie Explorer operated within severe graphical limitations: low-polygon character models, limited draw distance, and a fixed camera angle system common to early 3D platformers. The design philosophy, as described by multiple sources, was explicitly to create a “Tomb Raider-esque arcade adventure” for young gamers. This presented a fundamental contradiction: Tomb Raider‘s appeal lay in its then-revolutionary 3D movement, dark atmosphere, and implied violence (puzzle-solving often led to combat). How does one abstract “exploration” and “puzzle-solving” while removing all conflict? The solution—a game with no attack mechanic, where hazards are passive animals—defines the entire experience.

The Gaming Landscape of 2001:

The year 2001 was a watershed for 3D action-adventure games. Tomb Raider: Chronicles and Devil May Cry released, pushing the genre forward. Meanwhile, the “platformer” genre was in a transitional phase, with Crash Bandicoot and Spyro defining the PS1’s family-friendly 3D space. Barbie Explorer entered this landscape not as an innovator but as a very specific niche product: a licensed game attempting to borrow the prestige of a mature franchise while delivering the safety of an “Everyone” ESRB rating. Its closest analog was likely The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998), but stripped of combat and narrative depth, reduced to pure traversal and light puzzle-solving.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Reporter Without a Byline

Plot Structure and Pacing:

The narrative, as summarized across MobyGames, Wikipedia, and Alchetron, is deliberately thin and functional. Barbie is a reporter for a local museum who discovers a fractured “Mystic Mirror” with the power to unlock great power (a vague, MacGuffin-esque threat). Her mission is journalistic in name only; she immediately transitions to a treasure-hunting adventurer. The structure is geographically episodic:

1. Tibet: The “Ruby Mask” is retrieved.

2. Egypt: The “Emerald Beetle” is secured.

3. Africa: The “Sapphire Shield” is claimed.

4. Babylon (unlockable): The final “Golden Statue” is found.

Each region contains three platforming/puzzle levels culminating in a boss fight. The game ends with a brief cutscene of Barbie reassembling the mirror at the museum, restoring it to power. The plot has no character development, no dialogue beyond a basic premise, and no stakes beyond the abstract “power” of the artifact. It is a skeleton narrative, a series of locations strung together by a collector’s objective.

Characterization and Themes:

Barbie herself is a pure, silent protagonist. She has no personality, voice lines, or reactions. She is a vessel for the player’s actions, a stark contrast to the narrative-heavy Barbie animated films of the era. This aligns with a gameplay-first philosophy but feels jarringly empty. The supporting cast is virtually non-existent; the only named other character is Theresa, who appears solely as the rival in the two-player “Hot Seat” mode.

Thematically, the game explores non-violent adventure and global exploration. The choice to remove combat entirely is its most significant thematic statement. Hazards are environmental (gaps, falling rocks) or passive creatures (camels, elephants, goats that wander randomly). Even the bosses—a giant python in Africa and a sentient flytrap in Babylon—are environmental puzzles first, requiring pattern recognition and avoidance rather than assault. This creates a curious dissonance: the game borrows the aesthetics of dangerous, exotic locales (the “Darkest Africa” and “Egypt Is Still Ancient” tropes noted by TV Tropes) but strips them of their traditional danger, replacing potential human antagonists with indifferent wildlife. The theme becomes one of navigation and observation rather than conquest. Barbie is an explorer and documentarian, not a warrior.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Platforming Core

Core Loop and Movement:

At its heart, Barbie Explorer is a 3D platformer with puzzle elements. The core loop is: navigate a linear, obstacle-filled level, avoid hazards, reach the end to trigger a boss puzzle, and collect a shard. Movement is the game’s primary verb. The player can walk, run, jump, dive (a forward dodge-roll), and climb specific surfaces. The camera is fixed in most areas, a common PS1-era technique that simplifies level design but can create awkward sightlines.

The most innovative mechanic is the Power-Up Shoe System. Scattered throughout levels are different pairs of shoes that grant new abilities when collected:

* Spring Shoes: Provide extra jump height, essential for reaching higher platforms.

* Hiking Boots: Improve traction on slippery slopes, preventing accidental slides.

* (Implied) Other Shoes: Mentions of a “wide variety” suggest others like “swim fins” or “running shoes,” though the core sources don’t enumerate them all. This system is a direct response to the platforming challenges, making progression feel like incremental ability acquisition, a light echo of the Metroidvania genre.

Puzzles and Bosses:

Puzzles are primarily environmental and traversal-based: activating switches to open gates, navigating moving platforms, timing jumps over rolling boulders, and using the new shoe abilities to access previously unreachable areas. There is no inventory or item-combination puzzle system.

Bosses are unique to each region and function as final environmental puzzles:

* Africa: Giant Python. The player must likely avoid its lunging attacks while navigating its arena to reach a goal.

* Babylon: Sentient Flytrap. Shoots darts, requiring dodging.

These are not combat encounters; they are the culmination of the level’s movement and evasion challenges.

Two-Player Mode:

A notable feature is the Hot Seat multiplayer mode. As per MobyGames’ specs, “Barbie competes with Theresa to complete levels, with the goal to lose the fewest number of lives and collect the most gems.” This is a turn-based race where players take turns controlling Barbie on the same level, comparing scores at the end. It’s a simple, low-tech solution for a console without online play, encouraging competitive platforming without simultaneous action.

Critical Divergence: Control and Challenge:

Here lies the game’s most contested aspect. PSX Nation’s J.M. Vargas is scathing: the controls are “unbearable,” “rigid,” and “mannequin-like,” transforming platforming into a “plague.” He sees no challenge. Conversely, GameZone’s Michael Lafferty praises the “nonstop action” and “predictable arcade style.” The source material doesn’t allow for a definitive technical breakdown, but the divergence suggests a game with a high skill floor and low skill ceiling. Basic movement may feel stiff and imprecise (the “rigid” critique), but mastering the dive roll, jump timing, and shoe-ability use likely provides a consistent, if not deep, challenge. The lack of an attack and the passive nature of most hazards means failures are almost always the player’s fault due to a mistimed jump or misreading a platform’s movement—a pure platforming test. The accusation of “no challenge” from PSX Nation likely stems from a comparison to the precise, combat-integrated platforming of Tomb Raider or Crash Bandicoot, not from the game being easy, but from being unforgivingly simplistic in its interactions.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Postcard Adventure

Visual Direction and Atmosphere:

With the PS1’s hardware, Barbie Explorer employs low-polygon 3D models with texture-mapped environments. The art direction aims for a “toyetic” realism, placing a plastic-looking Barbie model into ersatz representations of global locales. Screenshots from MobyGames and LaunchBox confirm a bright, saturated color palette consistent with the Barbie brand. The four regions are visually distinct in a broad-strokes way:

* Tibet: Expect snow-capped peaks, pagodas, and icy blues.

* Egypt: Sandy textures, pyramids, hieroglyphic iconography.

* Africa: Lush greens, muddy browns, out-of-place temple ruins.

* Babylon: Mesopotamian ziggurats and desert hues.

The atmosphere is never dangerous or foreboding. It is a theme-park version of exoticism, clean and sanitized. The “animal hazards” (camels, elephants, goats) are rendered as harmless obstacles, emphasizing play over peril. This aligns perfectly with the ESRB “Everyone” rating and the Barbie brand’s ethos, but it creates a cognitive disconnect: the setting suggests adventure, but the gameplay mechanics mandate a stroll.

Sound Design:

The source material is utterly silent on the game’s audio. No reviews mention the soundtrack or sound effects. This is a significant gap. One can infer a typical PS1 library: a looping, upbeat, MIDI-based pop or “world music”-flavored score to match the exotic locales, and basic sound effects for jumps, item collections (the “gem” sound), and animal noises. The absence of critical commentary suggests the audio was functionally adequate but forgettable—a common trait in licensed games of the era where audio often received secondary priority to meeting the visual “look” of the license.

Reception & Legacy: Critical Split and Cultural Amnesia

Contemporary Reception (2001-2002):

Critics were divided, resulting in a MobyGames average of 64%, reflecting the polarized nature of the few reviews available.

* GameZone (80%): Championed the game as a successful adaptation. It acknowledged the “predictable arcade style” but celebrated the “nonstop action” and its successful cashing-in of the Tomb Raider formula for a younger audience. This review sees the game’s simplicity as its strength—a pure, accessible platformer.

* PSX Nation (61%): Provided the harshest critique. It dismissed the game as a “G-rated Tomb Raider clone” with “no challenge” and “atrocious” animation. The controls are singled out as “unbearable.” This perspective views the game’s compromises not as adaptations but as failures to meet even basic genre standards.

* Jeuxvideo.com (10/20 or 50%): Echoed the control complaints, calling the platforming phases a “veritable plague” due to “too rigid” maneuvering. It concluded the game was “very average, without great quality or real originality,” arguing it alienates both its target audience and genre fans. The French review’s final barb—”N’est pas Indy qui veut” (“Not everyone can be Indy”)—sums up the sense of overreaching aspiration.

* 7Wolf Magazine (65%): Offered a middle ground from a later (2003) Russian-language perspective, calling it “pretty good finger gymnastics.” It appreciated the varied locations and non-violent gem-collecting, noting its potential appeal beyond “little girls.”

Player reception, as measured by the 1.7/5 average on MobyGames from six ratings, is notably lower than the critic average. This suggests that while critics might have granted it some leniency as a licensed kids’ game, the actual audience (presumably parents buying for children, or curious players) found it less engaging, possibly due to the control issues and perceived blandness.

Legacy and Historical Position:

Barbie Explorer has no meaningful influence on the video game industry. It left no design descendants, spawned no sequels, and is rarely cited in discussions of platformer history. Its legacy is purely contextual:

1. A Peak into “Pink” Game Development: It represents a specific, now-largely-discarded model of “girls’ game” development in the early 2000s: take a popular “boy’s” genre (3D action-adventure), strip out violence and complexity, apply a friendly license, and hope for the best. Its failure on its own terms (controls, engagement) highlights the superficiality of this approach.

2. Runecraft’s Portfolio: It is a typical, mid-tier entry in Runecraft’s catalog of licensed titles. The studio’s fate (it ceased operations in the mid-2000s) is not tied to this game, but it exemplifies the contractual, work-for-hire nature of much licensed game development.

3. A Pre-“Barbiecore” Artifact: Released two years before the Barbie film franchise’s more modern, aspirational turn, and two decades before the cultural reckoning of the 2023 Barbie movie, this game captures a moment where Barbie’s digital adventures were safe, repetitive, and mechanically conservative. It is the antithesis of the self-aware, thematically rich narrative that would later define the brand’s renaissance.

4. A Curiosity for Genre Archivists: For historians of 3D platformers, it serves as a data point on the diversity of the genre on the PS1, demonstrating how developers experimented with core tenets (combat, collection, precision) within tight constraints. Its “no attack” rule is a fascinating deviation that, in execution, likely limited rather than expanded its appeal.

It is a game more often documented (on sites like MobyGames, Wikipedia, and TV Tropes) than played or remembered. Its current value lies almost exclusively in its status as a preserved artifact.

Conclusion: The Unadventurous Explorer

Barbie Explorer is not a lost classic. It is a compromised product that embodies the tensions of its time: the struggle to make “girls’ games” that weren’t patronizing but also weren’t simply reskinned “boys’ games”; the technical ceiling of the aging PlayStation; and the economic reality of low-budget licensed development. Its most audacious idea—removing combat entirely from an action-adventure framework—was either its most visionary or its most fatal flaw, depending on one’s perspective. The execution, marred by widely criticized “rigid” controls and simplistic design, failed to compellingly realize this vision.

Its 64% critic average tells the story of a very divided, very niche product. It offered exactly what it promised: a sanitized, globetrotting platformer. For a child in 2001 with a preference for jumping puzzles over shooting mechanics, it might have been a perfectly acceptable way to spend an afternoon. For anyone else—the genre enthusiast, the skeptical parent, the critic—its lack of challenge, depth, and polish was glaring.

In the grand tapestry of video game history, Barbie Explorer is a single, faded thread. It contributed no mechanics, spawned no trends, and is remembered by almost no one. Yet, its very existence is historically valuable. It is proof that the industry tried, and failed, to seamlessly graft serious adventure game syntax onto a doll brand in a way that felt authentic. It stands as a quiet monument to the era when “Barbie video game” meant “simple platformer,” before the brand’s digital future would be reimagined. Its place in history is not one of honor, but of clear-eyed documentation: a curious, flawed, and ultimately forgettable attempt to let Barbie be an explorer, trapped in a game that could never quite escape its own limitations.