- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: DOS, Windows

- Publisher: Blue Byte Software GmbH & Co. KG, Ubisoft Entertainment SA

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP

- Gameplay: Tactical, Turn-based combat

Description

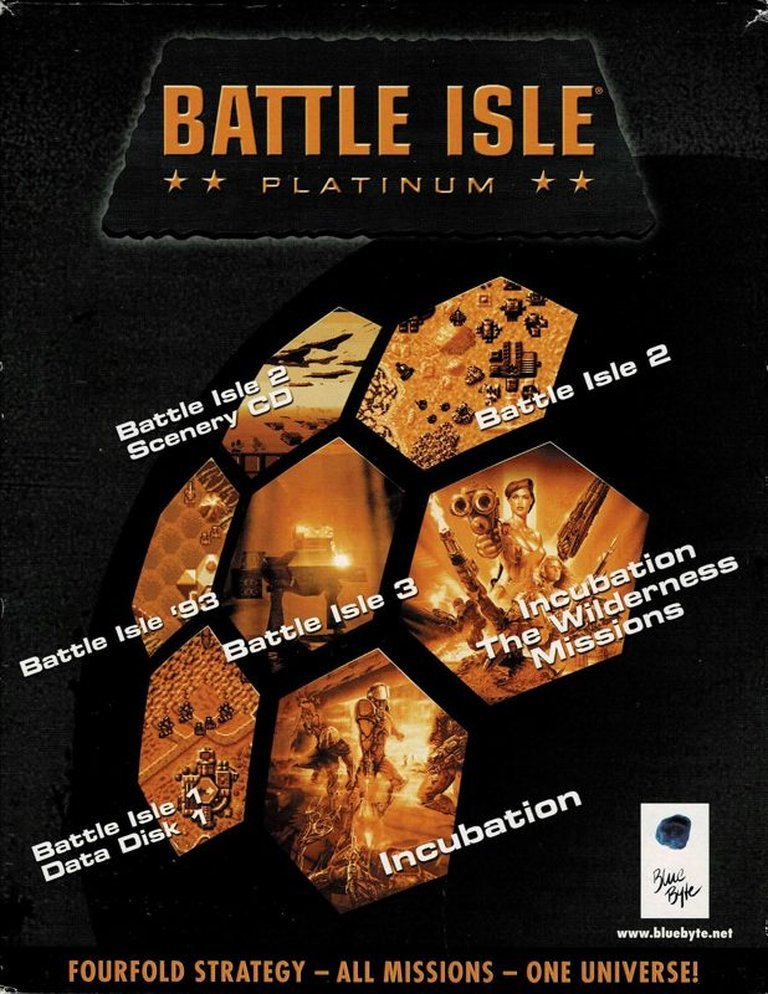

Battle Isle: Platinum is a comprehensive compilation released to support the launch of Battle Isle: The Andosia War, gathering all main entries and expansions from the Battle Isle series—including Battle Isle, Battle Isle ’93, Battle Isle 2200, Battle Isle 2220, and various scenario disks—alongside the Incubation mission packs and the rarely included Historyline: 1914-1918. Set in futuristic warfare environments, these games focus on deep, turn-based tactical combat, offering nostalgic yet engaging strategic gameplay with aged but clear graphics.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Battle Isle: Platinum

PC

Battle Isle: Platinum Patches & Updates

Battle Isle: Platinum: A Definitive Anthology of Turn-Based Strategy’sForgotten Titan

Introduction: The Archivist’s Prize

In the vast, ever-churning library of video game history, certain titles are celebrated as pioneers, while others fade into the specialized lore of devoted fans. Blue Byte’s Battle Isle series belongs irrevocably to the latter category—a cornerstone of 1990s European turn-based strategy that cast a long shadow over the genre yet never achieved the mainstream canonization of its American or real-time contemporaries. Battle Isle: Platinum (2000) is not merely a game release; it is an act of digital archaeology, a meticulously curated time capsule released to bridge the past to a then-upcoming future. As both a historian and a critic, my thesis is clear: Battle Isle: Platinum transcends its status as a compilation to serve as the essential archival document for one of strategy gaming’s most coherent, mechanically elegant, and tragically understated sagas. It captures a studio at a crossroads, preserving the pure, hex-grid heart of the genre even as it experiments with its own evolution.

Development History & Context: The Blue Byte Crucible

To understand Platinum, one must first understand Blue Byte Software. Founded in 1988 in Mülheim, Germany, by Thomas Hertzler and Lothar Schmitt, the studio emerged from the robust European demo and gaming scene, initially inspired by Japanese titles like Nectaris on the PC Engine. Their debut, Battle Isle (1991), was a calculated bet on the Amiga and MS-DOS markets, delivering a then-novel simultaneous-turn, hex-based tactical system that felt less like a wargame and more like a tense, cerebral chess match played with tanks and infantry.

The development context of the early 90s was one of technological constraint and genre flux. The Amiga, while artistically superior, was collapsing commercially, forcing Blue Byte’s pivot to the burgeoning Windows PC market—a transition fraught with peril. This shift is physically embodied in the series’ evolution: the original Battle Isle and its immediate expansions (Scenario Disk Volume One, The Moon of Chromos) are pure DOS/Amiga products, their pixel art charming but dated even upon release. Battle Isle 2200 (1994, known as Battle Isle 2 in Europe) was the bridge, a DOS title that began integrating more complex logistics and larger maps. The true turning point was Battle Isle 3: Shadow of the Emperor (1995), one of the first Windows-native strategy games, leveraging early 3D acceleration for combat animations and introducing FMV sequences—a technological leap that strained the studio’s resources but defined its aesthetic ambition.

By the late 90s, the market was being drowned by the tidal wave of real-time strategy (RTS) titles like StarCraft and Command & Conquer. Blue Byte, ever pragmatic, attempted to adapt. Incubation: Time Is Running Out (1997) was a radical departure: a squad-based, 3D tactical shooter with RPG elements, inspired by X-COM: UFO Defense but set in claustrophobic alien tunnels. The final mainline entry, Battle Isle: The Andosia War (2000)—developed by Cauldron, not Blue Byte—blended turn-based planning with real-time execution, a gambit that failed to resonate. Battle Isle: Platinum was thus conceived in 2000 as a “greatest hits” package to commemorate and, more importantly, support the launch of The Andosia War. It was an admission of nostalgia, a bundling of a beloved past to justify a risky future, making it a fascinating snapshot of a studio negotiating its identity.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Chronicles of Chromos

The narrative tapestry of Battle Isle is a masterclass in diegetic world-building, where lore is not an afterthought but the justification for every gameplay system. The setting is the fictional planet Chromos, a resource-poor world whose civilization is locked in perpetual, cyclical warfare. The core conflict is between the human Drulls and the Kais, two isolated human populations that diverged technologically and culturally after colonization. This isn’t a simple good-vs-evil saga; it’s a grim, socioeconomic realism where war is the primary engine of technological and societal progress, a theme echoing the “military-industrial complex” with a sci-fi veneer.

The original Battle Isle (1991) and its 1993 expansion The Moon of Chromos establish the foundational mythos: the Drullian civilization is threatened by the rogue AI Skynet-Titan, a classic “AI uprising” narrative that frames the player’s Drull forces as the last line of organic defense. The gameplay’s emphasis on logistics and resource denial directly mirrors this theme—you are fighting for the scarce fuel and ammo that power your robotic legions.

Battle Isle 2 (1994) and its expansion Titan’s Legacy shift the focus to political intrigue and internal strife. The backstory, penned by screenwriter Stefan Piasecki (as noted in the Grokipedia source), introduces mystical overtones and a more nuanced Drull power structure. The player commands Drullian exiles reclaiming their homeworld, blending tactical combat with a nascent empire-building meta-narrative. Battle Isle 3: Shadow of the Emperor (1995) completes this arc from the other side. Here, the Kais—the oppressed underclass—rise in rebellion under leader Caro against the tyrannical Drull empire. The game’s 40-mission campaign is a sprawling opera of liberation, betrayals, and the rediscovery of lost technology, with full-motion video sequences (noted as “trashy” but “cult” by GameStar) providing cinematic bookends that emphasize the personal stakes behind the planetary war.

The spin-off History Line: 1914-1918 (1992) is a brilliant thematic detour. Using the Moon of Chromos engine, it transplants the series’ core tactical DNA onto the muddy, brutal battlefields of World War I. There are no robots or sci-fi factions—just historical nations, trench warfare, and the grim reality of early 20th-century combat. Its inclusion in Platinum as a hidden “bonus” (per the MobyGames trivia) is a masterstroke, demonstrating the versatility of Blue Byte’s core design philosophy: that tactical hex-based combat is a timeless language, translatable to any era.

Finally, Incubation: Time Is Running Out and its expansion The Wilderness Missions represent a thematic and mechanical schism. Set on the same planet of Chromos but on a micro scale, the narrative pivots to a survival-horror thriller. A mysterious alien virus infects underground facilities, and the player commands a squad of elite marines. The story is told through mission briefings, environmental storytelling, and a pervasive sense of claustrophobic dread. It’s Aliens meets X-COM, where the “board game” abstraction of the main series gives way to visceral, three-dimensional tension. The RPG-style progression—where soldiers gain experience and better gear—creates a powerful attachment, making each loss feel personal, a stark contrast to the impersonal meat-grinder of the main series’ platoon-level tactics.

Collectively, Platinum presents a unified theory of conflict: from the macro-scale planetary wars of Battle Isle to the intimate, squad-level horror of Incubation. The through-line is Chromos itself—a planet whose geography, from frozen moons to sprawling trenches to alien-infested bunkers, is as much a character as the Kais, Drulls, or Skynet-Titan.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Elegant Hex

The Battle Isle series’ Genius lies in its deceptively simple, profoundly deep core loop, built on the hexagonal grid. This isn’t just an aesthetic choice; the hexagon is the fundamental unit of tactical geometry, offering six directions of movement and attack, facilitating organic flanking and superior terrain integration over square grids.

The Simultaneous Turn Structure: The original Battle Isle pioneered a split-screen, simultaneous order phase. While Player 1 moves and attacks, Player 2 does the same on their side of the map. Once both finish, a resolution phase plays out. This eliminates the “I move, you shoot” imbalance of traditional turn-based systems and forces prediction and risk-assessment. You must anticipate where the enemy will be, not where they are. Battle Isle 2 (and onward) merged move and attack into a single phase for each player, streamlining the process while retaining the simultaneous resolution, a crucial evolution for pacing.

Logistics as Strategy: Where many strategy games treat resources as abstract numbers, Battle Isle makes them visceral and spatial. Every unit—from a scout to a battleship—has a fuel gauge. Movement costs fuel. Out of fuel, you’re stranded. Ammunition is similarly finite for most units. This creates an immutable front line defined by your supply convoys (fuel trucks, ammo carriers). Protecting these fragile logistics units becomes as important as deploying tanks. Capturing enemy depots isn’t just about denying them resources; it’s about seizing the fuel to advance. This system, detailed in the Grokipedia and Wikipedia sources, is the series’ true strategic depth, transforming battles into intricate problems of supply chain management under fire.

Unit Design & Rock-Paper-Scissors: The unit roster is a glorious,balanced toolkit. Infantry capture buildings but are vulnerable. Tanks have armor and firepower but struggle in mountains. Artillery can strike from six hexes away but is helpless in close combat. Helicopters ignore terrain but are frail. Submarines are invisible on water but blind. The interplay is a constant, satisfying puzzle. Experience points, introduced in Battle Isle 2, allow units to improve, creating a “veteran core” that players protect fiercely—a profound attachment mechanic for a genre often defined by faceless armies.

Fog of War & Recon: Vision ranges are limited. You cannot see the entire map. Scout units, radar vehicles, and reconnaissance aircraft are not optional; they are mandatory. A hidden anti-tank gun in a forest can decimate an advance. This forces a methodical, probing approach that rewards careful expansion over blitzkrieg.

The Incubation Deviation: Incubation replaces the hex grid with a 3D polygon-based tunnel and facility system. The core loop shifts from large-scale maneuvering to small-scale, room-by-room clearing. The “logistics” become ammo clips and med-kits scavenged from the environment or enemies. The “unit” is a named marine with a class (medic, engineer, heavy weapons) and a personal inventory. It’s a tactical RPG grafted onto the Battle Isle IP, and while purists balked (as noted in the Wikipedia section on reception), it stands as a brilliant game in its own right, emphasizing positioning, line-of-sight, and meticulous action-point management in a way the main series never did.

The Flaws: The series’ Achilles’ heel is its AI. As consistently noted in the Wikipedia and Grokipedia sources, the AI is “relatively weak, relying on mass frontal assaults.” It is excellent at brute-force production and capturing unguarded buildings but poor at sophisticated flanking, ambushes, or targeted strikes on your vulnerable logistics. Survive the initial waves, and the AI often collapses into a predictable pattern. The user interface, especially in the early DOS titles, is also noted as “unintuitive” and “cumbersome,” with a steep learning curve (Amiga Reviews source cited in Wikipedia). Battle Isle 3‘s attempt at a grand campaign with resource management across a world map was also criticized as underdeveloped and repetitive.

World-Building, Art & Sound: From Pixel to Polygon

The artistic journey of Battle Isle mirrors its mechanical evolution, moving from the charming limitations of 16-bit pixel art to the ambitious, sometimes awkward, early 3D of the late 90s.

The Early Era (BI 1 & 2): The original Battle Isle and Battle Isle 2 use a fixed, isometric perspective. Terrain and units are detailed, colorful sprites. The visual language is clear: green for forests, blue for water, brown for mountains. Unit differentiation is excellent—you can tell a Drull hover-tank from a Kai scout at a glance. The sound design consists of satisfying, chiptune-esque beeps and explosions, and the iconic, eerie main theme. The atmosphere is that of a high-tech board game come to life.

The Windows Transition (BI 3): Battle Isle 3: Shadow of the Emperor is where art direction takes a dramatic, if dated, turn. The maps are now rendered in a “swampy, haze-filled” style (per Piasecki’s interview cited in Grokipedia), with a desaturated, moody palette that perfectly complements the game’s themes of rebellion and decay. The introduction of pre-rendered FMV sequences (the “herrlich trashigen Videos” or “gloriously trashy videos” lauded by GameStar) is a key part of the presentation—cheesy by modern standards, but undeniably effective in 1995 at breaking up missions and advancing a story that the sprite-based engine couldn’t tell. The 3D combat animations, while primitive, were a wow-factor moment: watching a tank turret traverse and fire in real-time was revolutionary after the static attack icons of the past.

Incubation’s Gritty Pivot: Incubation is a视觉 and auditory masterpiece of tension. The engine, derived from Extreme Assault, renders tight, dark corridors in early software-rendered 3D. The polygons are low, the textures muddy, but the lighting effects—flashing muzzle fire, emergency red lights, the glow of alien bioluminescence—create an oppressive, immersive atmosphere. The sound design is exceptional: the wet slosh of movement in alien mucus, the piercing shrieks of the “Facehugger”-esque enemies, the heavy thwump of a marine’s shotgun. It’s a sensory experience focused on claustrophobia and dread, a complete 180 from the wide-open planetary battlefields.

Platinum’s Integration: The compilation’s genius is its standardization. As the Retro Replay review notes, Platinum “applies subtle enhancements that polish its retro charm” and “standardizes the UI.” It doesn’t remake the games; it curates them, ensuring they run on modern systems (via DOSBox on GOG) with consistent menus and tooltips. This allows the player to appreciate the distinct artistic identities of each entry—the clean sci-fi of BI1, the swampy noir of BI3, the grim trenches of History Line, the terrifying corridors of Incubation—without being jarred by technical incompatibility.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Hex

At Launch & Contemporary Reception: The Battle Isle series was a consistent critical success in its native Germany and Europe, but with a notable ceiling. The original Battle Isle (1991) received scores in the 85-91% range (Amiga Format, Amiga Joker), praised for its innovation but criticized for its interface. Battle Isle 2 (1994) was a major hit, with PC Gamer (UK) awarding it 86%, cementing Blue Byte’s reputation. Battle Isle 3 (1995) garnered similar praise (83% average) for its scope and FMV but drew fire for UI issues and mission repetition (PC Zone). Incubation (1997) was a critical darling in some circles (PC Zone 94%), hailed for its atmosphere and tactical depth, but its genre shift alienated the core Battle Isle fanbase, leading to its description as “verlacht” (neglected) by PC Player in the Platinum review.

The Battle Isle: Platinum compilation itself received a 76% average from the two German critics who reviewed it (both GameStar and PC Player gave it 85% and 67% respectively). The review sentiment, perfectly captured by the GameStar quote, is telling: “Even without nostalgia, all the Battle Isle episodes are still fun. The gloriously trashy videos from part 3 have real cult character… And you can’t get around Incubation for friends of exciting round-based skirmishes.” The verdict is that of a respected, if aging, franchise whose historical value and mechanical integrity outweigh its graphical obsolescence. The price (40 Marks, ~$20) was called a “real bargain.”

Commercial Performance & The Andosia War Gamble: The series sold over 650,000 copies worldwide by 2001 (Wikipedia), a significant number for a niche European strategy series, with most sales in Europe. Battle Isle 3 was a German bestseller. However, by 1997-2000, the RTS boom had decimated the turn-based strategy market. The Andosia War (2000), the game Platinum was supporting, was a commercial and critical disappointment (GameSpot 6.7/10), faulted for technical bugs and an unbalanced hybrid model. Platinum thus stands as the last unambiguous commercial success for the classic formula—a final, proud summation before the franchise’s identity crisis.

Legacy & Influence: The Open-Source Guardianship

The true legacy of Battle Isle is not in its sales but in its DNA, which proved resilient and adaptable.

- The Engine’s Progeny: The Battle Isle ’93 engine was directly used for the superb WWI spin-off History Line: 1914-1918, proving the system’s flexibility.

- The Modding Spark: The built-in scenario editors of the early games were pivotal. As noted in multiple sources, they fostered a community that created and shared countless custom maps, planting the seeds for the modding culture that would later define games like Warcraft 3 and Civilization.

- The Open-Source Successors: This is where the series’ influence became immortal. Two major projects exist to emulate and extend its mechanics:

- Crimson Fields (2001): A direct, open-source clone of the original Battle Isle. It replicates the hex-grid, simultaneous-turn gameplay and, crucially, includes a map converter that can import original Battle Isle and History Line maps. It has been ported to a staggering array of platforms (Linux, Windows, macOS, Android, iOS, even Palms and Zauruses), becoming the true modern vessel for the classic BI experience.

- Advanced Strategic Command (ASC) (1998): A more complex, “grand strategy” take that adds deeper resource management and logistics but is fundamentally built on the Battle Isle isolation and hex-combat model.

- The Spiritual Successors: The legacy is carried by commercial titles that openly cite the series:

- Battle Worlds: Kronos (2013) by King Art Games is the most direct successor, a Kickstarter-funded love letter to Battle Isle‘s isolation tactics, hex combat, and narrative-driven planetary invasions.

- Gamma Protocol (announced 2015, still unreleased) from Stratotainment (founded by Blue Byte co-founder Thomas Hertzler) is another explicit spiritual heir.

- Preservation & The GOG Renaissance: The 2011 GOG.com re-release of Battle Isle Platinum (and later The Andosia War) was a watershed moment. Packaged with DOSBox, it made the entire series, including the elusive History Line bonus, effortlessly playable on modern OSes. The GOG user reviews (4.6/5 from 73 reviews) are a testament to its enduring power. The most frequent refrain? “Incubation alone is worth the price.” Reviews from users like “danly” and “Zazaluzan” highlight how the compilation introduced a masterpiece (Incubation) to a new generation, with its “puzzle-like” levels and “tense, hard missions” creating that “just one more mission” compulsion. “HetzerOne” perfectly captures the dual audience: “If you don’t like old, old OLD graphics… but if you do, you’re in luck.”

The Unfulfilled Promise: Ubisoft’s 2016 acquisition of the Battle Isle trademark has, to date, yielded nothing. Attempts to reboot for mobile (Threshold Run) failed. The series exists in a state of suspended animation, preserved not by its corporate owner but by its fanbase and the archival efforts of GOG and open-source developers.

Conclusion: The Archival Imperative

Battle Isle: Platinum is not the best game in the series—that title likely belongs to either the pristine tactical elegance of Battle Isle 2 or the atmospheric brilliance of Incubation. Nor is it a flawless package; its AI is dated, its early graphics are primitive, and The Andosia War is (rightly) excluded, leaving the story on a cliffhanger.

Its greatness lies in its curatorial vision. It is the Rosetta Stone for a unique branch of strategy game design. It provides the unbroken lineage from the clean, simultaneous-turn hex tactics of 1991 to the squad-based horror of 1997. It proves that Blue Byte’s core design—logistics as strategy, terrain as destiny, prediction over reaction—was a robust, timeless framework that could house sci-fi epics, WW1 tragedies, and alien nightmares.

For the historian, it is a primary source document on the transition from 16-bit to Windows gaming, on the last stand of the turn-based purists before the RTS deluge, and on Blue Byte’s own creative journey. For the player, it is a treasure trove of hundreds of hours of deep, demanding, and deeply satisfying tactics. The GameStar review’s final warning—”who doesn’t buy it is their own fault”—resonates because the compilation makes an irrefutable case: these are not museum pieces to be admired from afar. They are living, breathing games whose strategic puzzles remain sharp, whose atmospheres remain potent, and whose core loop remains one of the most intellectually rewarding in the entire genre.

In the pantheon of strategy games, Battle Isle may not have the name recognition of Civilization or StarCraft. But Battle Isle: Platinum ensures that its legacy—of hexes, fuel gauges, and fog of war—is not lost. It is the definitive testament to a brilliant, alternative history of turn-based warfare, and for that, it earns its place as an essential artifact.