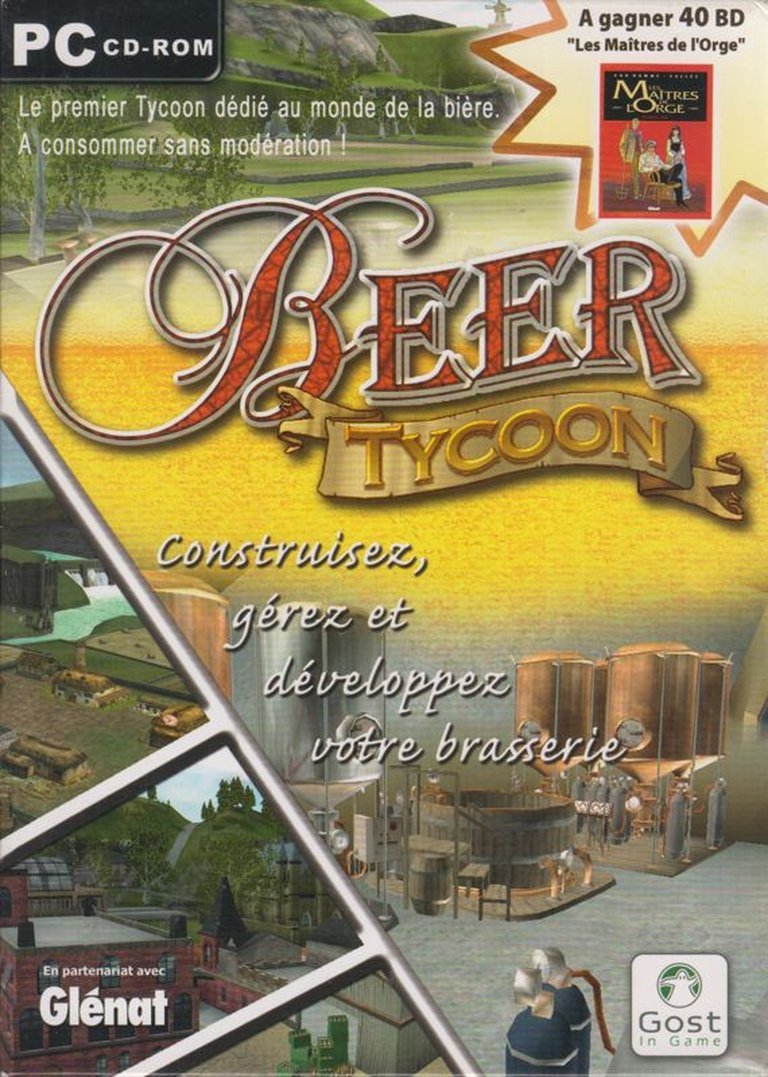

- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Frogster Interactive Pictures AG, GOST Publishing SPRL, Noviy Disk

- Developer: Virtual Playground Ltd.

- Genre: Simulation, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Business simulation, Managerial

- Setting: Alcohol

- Average Score: 48/100

Description

Beer Tycoon is a strategic management simulation where players launch a microbrewery in the UK, Germany or Belgium and grow it into a full‑scale industrial operation, overseeing all stages of beer production—from conception and brewing to marketing and distribution—while juggling recipes, staff, equipment and finances to maximize profit.

Gameplay Videos

Cracks & Fixes

Patches & Updates

Beer Tycoon: Review

Introduction: The Frothy Promise and Bitter Aftertaste of an Overlooked Sim

In 2006, as indie craft brewing was experiencing its first renaissance in the real world, a curious niche simulation emerged: Beer Tycoon. Marketed as a chance to “become the ultimate beer tycoon” (Retrolorian), the game promised players the intoxicating dream of starting with a humble microbrewery in one of three European nations – Germany, the UK, or Belgium – and ascending to industrial-scale brewing magnate status. Developed by the UK-based Virtual Playground Ltd. and published by Frogster Interactive Pictures AG, Beer Tycoon was conceived as a thematic entry in the long, sometimes-fatigued “Tycoon” game lineage, a genre built on the empowering chassis of business simulation. It arrived at a time when the market was saturated with construction and management sims, from the deeply flawed Prison Tycoon (2005) to artistic ventures like RollerCoaster Tycoon 3 (2004), and even food-themed entries such as Pizza Connection 2. The thesis of this review is that while Beer Tycoon possessed a theoretically rich and thematically viable design framework—leveraging European beer heritage, complex production systems, and character-driven staff management—it was ultimately undone by a catastrophic fusion of technical inadequacy, systemic underdevelopment, and baffling design choices, resulting in a widely panned experience that squandered its unique premise and cemented itself as a cautionary tale of mid-2000s simulation failure. It is a textbook case of the ambition-to-execution gap: a game with the idea of depth, but none of the realization of it.

Development History & Context: Tycoon Alchemy Gone Sour

The development of Beer Tycoon in 2006 occurred within a gaming landscape defined by significant technological and market shifts. The DirectX 9/10 transition was in full swing, and PC hardware was becoming increasingly capable, supporting sophisticated 3D engines and physics simulations (PC Action, HCL.hr). The “Tycoon” subgenre, having been perfected by the original RollerCoaster Tycoon (1999) and its expansions, had been diluted by a glut of knockoffs—many of which were shallow, buggy cash-ins (GameStar explicitly calls Beer Tycoon a reskin of Prison Tycoon with a new skin, for 14% each). Virtual Playground Ltd., a relatively small UK studio, positioned itself as “tycoon experts” (HEXUS.net), suggesting a pattern of reusing core engine assets across themed titles. This is corroborated by the critical consensus: Beer Tycoon was a re-jig of Prison Tycoon (2005) (PC Action, GameStar, PC Games), indicating a policy of asset reapplication rather than genuine innovation. The publisher, Frogster Interactive, was known more for online multiplayer and MMO adaptations (like 2Moons) than for cutting-edge simulation design, further reducing expectations for deep systems.

Technologically, Beer Tycoon was built upon a proprietary 3D engine (Gamepressure, vgchartz), employing a top-down camera perspective with rotatable views, a common graphical approach for the genre. The recommended specs—a Pentium III 733 MHz, 256MB RAM, and a 16MB graphics card (Gamepressure)—indicate that the game was targeting the lower end of the market, technically, not pushing boundaries. It used a CD-ROM release model (MobyGames, MyAbandonware), a format already facing obsolescence by 2006-2007 in favor of DVD and digital downloads. Crucially, the game’s core differentiators were supposed to be brewing mechanics (recipe creation, ingredient selection), diverse staff with specializations, and player-designed advertising campaigns and visitor center tours (Gamepressure, vgchartz, Retrolorian, HEXUS.net), none of which were replicated in prior “Tycoon” titles. This put the burden on Virtual Playground to deliver what previous sims merely hinted at: deep, engaging, systems-based interaction with niche production processes.

However, the development must have been rushed or understaffed. Cutscenes are absent (evident from reviews and gameplay videos), character voices are nonexistent or limited to stock phrases (only name calling), and localized text contains garbled terms (e.g., “casks are bottles and bottles are casks in the marketing screen” per player Jay on MyAbandonware). The interface was universally criticized as “pitoyable” (catastrophic) (Jeuxvideo.com) and “confusing” (AG.ru, PC Games), with no intuitive integration between the character roster (54 unique staff), skill trees, equipment management, and financial planning. The vision—becoming a “druglord” of legal intoxicants (PC Action’s satire)—was bold, but the execution felt like a database list with some 3D models slapped over it. In context, Beer Tycoon was a failed attempt to port the immersive, systemic charm of early-2000s Euro-styled business simulations (like Hotel Giant or Wildlife Park) into the Tycoon franchise model, only to be torpedoed by reused code and insular systems.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Misplaced Realism and Flat Characters

Beer Tycoon presents essentially no traditional narrative. There is no script, no plot, no traditional cutscenes. Unlike RollerCoaster Tycoon with its eccentric owner, or Sim City with its implied civic hopes, Beer Tycoon relegates the protagonist to a faceless, voiceless CEO. The closest thing to a story is the gradual progression from micro-brewery in the countryside (UK), traditional cellar (Germany), or Belgian monastic town to a monolithic industrial factory, measured solely by financial balance and market share. This is not a story about craftsmanship, community, or even love of beer; it’s a ritual of industrial ascension. The brewer, the player, exists not to raise a pint, but to calculate COGS and avoid overheads, turning the romance of brewing into an accounting exercise.

Characters are reduced to job titles and skill displays. The game features 54 unique characters (Gamepressure, vgchartz) across 9 different career specializations, including brewers, marketers, logistics operators, and tourism guides. While this could have formed the basis of engaging AI personalities—imagine a seasoned brewer criticizes your laitram or a social media-savvy marketer pushes influencer posts—the game uses these characters as semi-animated cutouts that perform tasks. They don’t converse, they don’t leave complaints about pay, and they don’t retire. Their presence in the UI is largely decorative. The 9 types of consumers (Gamepressure) are abstract purchasing behaviors: they prefer light vs. dark beer, low vs. high ABV, bargain vs. luxury brands. But they never appear visually, nor do they evolve. A visitor tour might have presented guests sampling your flagship brew, but instead, it’s a flat line item in the finances, draining money with minimal return (MyAbandonware comments from Jay).

The dialogue (or equivalent) consists of in-system messages, music jingles when leveling up, and textual demand notices from the Beer Distribution Commission (Retrolorian mentions quotas). These are not quotes; they are bureaucratic micromanagement. The only thematic message is one of brutal capitalism: dominate the market, avoid penalty, and let architectural style—whether German efficiency, British quirk, or Belgian artistry—only matter for flavorless prestige. The so-called “golden beverage” is commodified before it’s even conceived. Unlike, say, Brewmaster’s Challenge (if such a game existed), there’s no celebration of flavor, heritage, or ritual—just profit algorithms. Even the alcohol theme, which could have been daring in a PEGI 3-rated title (MobyGames), is handled with Puritanical distance. The beer is never drunk, never gifted, never toasted. It is simply shipped. Beer, in Beer Tycoon, is the world’s most tragic spice.

The implied theme—rise from obscurity to greatness—is subverted by the game’s very loneliness. There is no multiplayer (VGChartz, Videogamegeek), no cultural events, no festivals, and no pet felines à la the Whiffers. You play in isolation, clicking through menus, as if managing a spreadsheet with a screen. The only celebration is a minor sound effect when you break another million. The result is a strangely anhedonic experience: the dream of ownership, but not enjoyment.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Where Systems Design Crumbled

At its core, Beer Tycoon is a business simulation game with strategy elements, divided into the four stages of beer production: conception, production, marketing, and distribution (Official Description, MobyGames). But beneath this four-chambered facade lies a labyrinth of undercooked, contradictory, and actively frustrating systems.

1. Recipe Design & Conception:

The game invites players to create recipes from 50 ingredients, including base malt, character malt, water types, hops, yeast, and “novelty flavorings” (Gamepressure, vgchartz, HEXUS.net). This sounds like a rich alchemy system. In practice, the interface is a spreadsheet-like grid (Jeuxvideo.com’s critique of the UI applies here), with no flavor pairing suggestions, no historical accuracy (e.g., no Reinheitsgebot checks in Germany), and no taste profiles. The only numeric output is popularity (for appeal) and cost (for profit calculation). Flavor is reduced to a DIUS (Design-In-Unity-Scoring) system. The player tweaks percentages in a vacuum, never seeing their creation celebrated—or mocked—by anyone. There is no “taste test” minigame. No feedback. Just a number. The “novelty flavorings” (chilli, chocolate, etc.) are cartoonish gimmicks, offering no real mechanical differentiation. This is not a brewer interface; it is a recipe optimizer calculator.

2. Production & Industry Simulation:

– Infrastructure: You can build 56 structures (Gamepressure) for the full brewing pipeline—mash tuns, fermentation tanks, casking/bottling lines, research labs, staff dorms, visitor centers, and even pubs. There’s 63 buildings with country-specific architecture styles (German, UK, Belgian). But the placement is clunky, with no “snapping” or production flow optimization. Pipelines are fictional.

– Equipment: All equipment (copper kettles, etc.) is purchased as a model, not a functional asset. The 56 brewing pieces include mash tanks, fermenters, bottling systems, but they are essentially real estate units. Machines don’t wear out, don’t need calibration, and don’t allow scaling up/down easily. You can’t see beer flowing inside.

– Staffing & Skills: The 54 staff members have specializations (e.g., Head Brewer, Sales Rep) and 9 careers, but their skills are only represented as static values on hiring. They don’t level, they don’t teach others, and they don’t make decisions. Training, raises, or team cohesion are nonexistent. Running costs are deterministic.

3. Marketing & Community:

This should have been the crown jewel—the social engine of the game. Instead, it is riddled with bugs. Advertising is set in a window where, critically, “casks are bottles and bottles are casks” (Jay, MyAbandonware). When a client asks for bottles, the game shows them receiving casks. The UI is internally inconsistent, a fatal flaw for a data-driven sim. Advert types exist (billboards, TV, radio), but their engagement is opaque. The pub and visitor center are cost sinks early on (Jay), as people don’t buy; tours are free or loss leaders. The “photo ops” are not proven to increase loyalty. The customer types (9) are abstract database filters.

4. Finance & Distribution:

The financial system is the most directly implemented. You track revenue, overhead, staffing, marketing spend, and fines. But it is persistently opaque. The critical issue: players cannot manually set prices (chaz, 2023 on MyAbandonware: “I could not sell 1 beer and never made 1 penny”). Demand is force-fed via clients and the Beer Distributors Commission, but there is no direct buy/sell menu or stock control. Storage visibility is broken: “you never really know how many of each type you have in storage” (Jay). This makes financial planning paralysis.

5. Progression, Pace, and Bugs:

– The three-tiered progression (micro → suburban → industrial) is clear, but advancement is gated by balance sheets, not community or expertise.

– The time cycle is slow. No fast-forward (MyAbandonware comments), even in the 2006-2007 era.

– Performance Issues: High-resolution textures cause lag, especially when selecting buildings (Jay, MyAbandonware); bugs in patch V1.07 are still unresolved; the installer/launcher UI is “just a grey box” (Zsold, MyAbandonware).

– No tutorial or manual integration causing new players to be overwhelmed.

The innovative systems—3D dynamically lit world, country-specific builds, recipe crafting, staff tracking—are deeply flawed by poor UI, inconsistent logic, and lack of player feedback. This makes Beer Tycoon a series of isolated minigames thrust together under a single theme, not a cohesive simulation.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Ambition vs. Aesthetic Theft

The game’s setting is its most convincing element, even if ultimately underutilized. Set across seven locations in three countries (Germany, Belgium, UK), Beer Tycoon leverages slightly distinct architectural styles for buildings (Gamepressure, vgchartz). The German locations tend toward clean, red-tiled roofs and industrial spires; the Belgian is cloistered, with gated entries and stone walls; the UK is idyllic, with thatched roofs and green hills. This allows for basic environmental storytelling: the player is not just expanding facilities, but inhabiting different brewing cultures.

The 3D engine (Gamepressure) supports dynamic time of day and shadows/lighting effects (vgchartz, HEXUS.net), with the camera offering rotatable views and a top-down Z-axis. Building models are detailed enough to distinguish a fermentation chamber from a bottling line. Equipment designs mimic real brewing machinery (HEXUS.net mentions “highly realistic models”), like copper kettles and conditioning tanks. This is the most authentically brewery-like visual language in any sim to date.

Yet, the presentation is stiff and inert. Towns do not expand organically; they are fixed maps. There are no pedestrians, no NPCs living lives outside your control. The landscape is static. The “artistic” UI—with 2D overlays for staff portraits, ad thumbnails, and financial graphs (Gamepressure, Jeuxvideo.com)—is cluttered and non-integrated. It belongs to a pre-COSMO era, incompatible with the 3D world. You click on a 3D building, and a 2D panel pops up with text. The transparency of data (Gamepressure) is meant to be a strength, but it’s a mess of pull-down menus and formulaic tables. Jeuxvideo.com called it “permanently bugged and confusing.”

Sound design is nearly nonexistent. No ambient noise from the tanks (hisps, gulps), no chatter in the pub, no ambient music during production. The score, when present, is forgettable. No voice acting. The only audio feedback is the occasional jingle when you upgrade or are fined. There is no use of diegetic sound (i.e., the sounds “in the world”), like a click when a bottle caps. The silence is deafening, amplifying the game’s emotional vacuum. Art direction, therefore, exists in tension: the ambition of 3D, realism, and dynamic systems are undermined by a sterile, cut-and-paste UI and absolute emptiness in audio and NPC life.

Reception & Legacy: The Subject of Subjective Purgatory

Beer Tycoon was a critical failure. The aggregate critic score on MobyGames is 24% (6 reviews), with extremes from a 5% (PC Games, Germany) to a high of 42% (PC Action, Germany). Only one review—Jeuxvideo.com (15%)—was even above 15%. The player score is 2.8/5 (MobyGames), and a 7.3/10 on Gamepressure (which appears divergent from the broader critical zeitgeist). The game holds #9,188 on the Windows MobyGames rankings (out of 9,282), near the bottom.

Key criticisms were universal:

– “Interface is pitoyable, les graphismes sont laid et le jeu est buggé jusqu’à la moelle.” (Jeuxvideo.com – 15%)

– “Design, betrunken zu ertragener Grafik und zum Saufen langweiligen Spielverlauf.” (GameStar – 14%, noting it’s a Prison Tycoon clone)

– “Dumm nur: Der Gefängnismanager bekam bei uns 14 Punkte. Weil sich am untergärigen Design… nichts geändert hat.” (PC Action – 42%, still negative)

– “Zaključak? Igru ne kupujte.” (HCL.hr – 34%, “Don’t buy this game.”)

– “Zum Saufen langweiligen Spielverlauf.” (PC Games – 5%, “Boring to drink to.”)

Even reviewers who recognized the concept (e.g., PC Action’s satire) dismissed the execution. Community forums echo this: MyAbandonware, the largest fan hub, is filled with bug fixes, compatibility guides, and frustrated play logs (chaz: “I could not sell 1 beer and never made 1 penny”). User comments (Jay) acknowledge the “setting” and “systems” were “the most ambitious,” but the game is “unpolished and buggy.” Retrolorian’s praise of realism and challenge feels more mythologized decades later.

Commercial performance is unreported, but the low number of collectors (11 on MobyGames), lack of sequels, and absence from retro marketplaces (compare to a 3,500-person collection base for RollerCoaster Tycoon) suggest sales were negligible. It did not spawn an industry of beer sims. There are no outcritic memorials, retrospectives, or God-tier RTS-style ASCOMP milestones. It is not “so bad it’s good”; it is just terrible.

Legacy? Beer Tycoon is now a curiosity. Mentioned in lists of “failed business sims,” “bugs, interface grotesquerie,” and occasionally “what if?” alongside games like Big Oil (2005, far better received). It is not a meme (alas, no Beer Tycoon GIFs trending on Twitter). It does not influence later games, except in the negative: a warning about UI, tutorial design, and thematic depth. The only hardware legacy is the optimizer communities on MyAbandonware, sharing patches and “to win without selling beer” exploits.

Conclusion: A Draft That Needed Bottling

Beer Tycoon is, in the end, a cautionary tale. Its vision—a deeply systemic, character-driven, flavor-conscious European brewing sim—was prescient in 2006, especially as the craft beer movement grew in the early 2010s. Its rejection of USA abstraction (no mass-market “Keg 385” beer) and embrace of cultural specificity (German cellar, Belgian abbey) showed real potential. The idea of playing as both CEO and brewer, of marketing your own beer, of running tourist tours—these concepts were ahead of their time and could even hold appeal now.

But Virtual Playground bottled the ferment too early. The UI was incomprehensible, the core economic engine was broken, the character systems were gimmicks, and the marketing module was riddled with bugs. The late 2000s Tycoon market craved clarity and polish; Beer Tycoon delivered clutter. It is not redeemable by nostalgia. Players didn’t fail. The game did. For the player seeking the satisfying accounting zen of a good sim, or the ludic perfectionism of balancing yeast vs. hop, Beer Tycoon offers only a headache and a hangover.

Final Verdict:

Beer Tycoon (2006) is one of the most catastrophically flawed business simulations ever released. It is not merely bad. It is fundamentally broken in its core systems and unplayable for many of its intended mechanics, a failure that extends beyond era constraints. It is not fondly remembered. It is studied—never played—as a case study in systems design hubris, UI myopia, and the peril of slapping a beer label onto a broken spreadsheet. In video game history, it is not a landmark. It is a landfill.

Score: 2.5 / 10 ★½

Reserved only for the concept and the few players who manage to debug the game into basic function (e.g., via Windows 11 compatibility layers). The score would be 1.0/10 for the authentic release. Modern retro players should seek *Brewmaster (hypothetical) or play RimWorld with brewing mods. Or, as critics suggested: buy a crate of Gerstensaft instead. At least then, you can drink to a wasted experience.*