- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH

- Genre: Compilation

Description

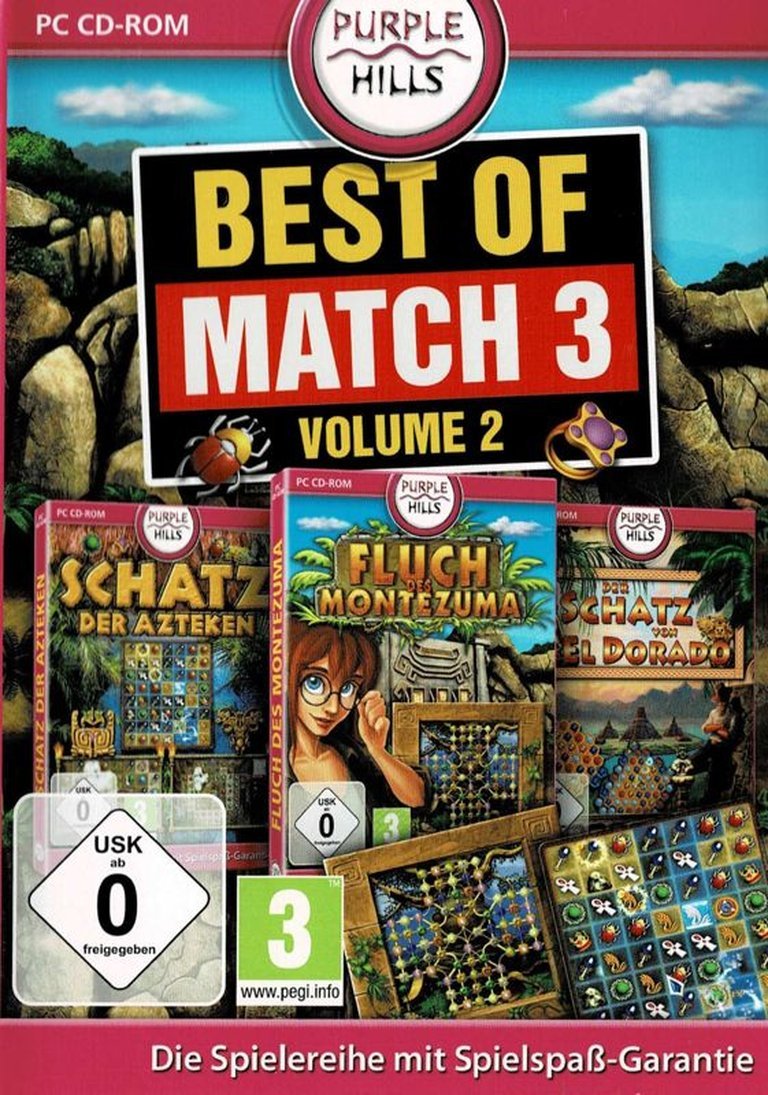

Best of Match 3: Volume 2 is a retail compilation released in 2010 for Windows, bundling three popular match-three puzzle games: ‘Schatz der Azteken’, ‘Curse of Montezuma’, and ‘Schatz von El Dorado’. Players embark on themed tile-matching adventures through ancient Aztec, Montezuma, and El Dorado settings, swapping gems and artifacts to progress.

Best of Match 3: Volume 2 Reviews & Reception

gamearchives.net : a throwback: a no-frills anthology for players seeking offline, session-based play without microtransactions

Best of Match 3: Volume 2: Review

Introduction

In the ever-expanding pantheon of casual gaming, few genres command the universal appeal and addictive simplicity of match-3 puzzle games. Released on December 10, 2010, Best of Match 3: Volume 2 stands as a curated artifact from an era when physical CD-ROM compilations dominated bargain bins and digital storefronts were just beginning to supplant retail shelves. Published by Germany’s S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH, this Windows-exclusive anthology bundles three titles—Schatz der Azteken (Treasures of the Aztecs), Curse of Montezuma, and Schatz von El Dorado (Treasure of El Dorado)—under one economical banner. While its commercial obscurity and lack of critical attention place it firmly in the realm of budget curiosities, this compilation serves as a fascinating time capsule of match-3’s foundational era. Its legacy lies not in innovation, but in its role as a utilitarian gateway to a genre that would soon explode into a multi-billion-dollar phenomenon. This review deconstructs Best of Match 3: Volume 2 through the lenses of its historical context, mechanical execution, and enduring relevance, arguing that despite its unremarkable execution, it exemplifies a transitional phase between the genre’s early pioneers and its modern mobile dominance.

Development History & Context

Best of Match 3: Volume 2 emerged from the niche ecosystem of European budget publishers like S.A.D. Software, which specialized in repackaging mid-tier casual games for cost-conscious markets. The studio’s vision was purely pragmatic: capitalize on the PC market’s appetite for affordable, accessible entertainment during the late 2000s, a period when digital distribution was gaining traction but physical media still held sway. Technologically, the compilation reflected the constraints of its era. Built on legacy engines optimized for DirectX 8.0 and requiring only a 128MB RAM Pentium processor, these games eschewed graphical sophistication in favor of broad compatibility. Their 2D tile-based graphics, static environments, and mouse-driven controls were relics of a pre-touchscreen, pre-F2P (free-to-play) design philosophy, prioritizing functional simplicity over immersion.

The gaming landscape of 2010 was transitional. Match-3’s popularity was burgeoning, fueled by PopCap’s Bejeweled (2001) and the rise of browser-based portals like MSN Games. Yet, the genre was still finding its identity beyond its Soviet-era origins (Shariki, 1994) and Western mainstream breakthroughs. Titles like Puzzle Quest (2007) had begun blending match-3 with RPG mechanics, but Best of Match 3: Volume 2 harkened back to a purer era of tile-swapping, devoid of hybridization or monetization. Its release coincided with the dawn of mobile gaming’s ascendancy, but its CD-ROM format and offline focus positioned it as a bridge between the genre’s desktop roots and its impending mobile renaissance—a last gasp of a bygone era before King’s Candy Crush Saga (2012) would redefine the genre’s commercial and design paradigms.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The compilation’s three titles—Schatz der Azteken, Curse of Montezuma, and Schatz von El Dorado—share a thematic uniformity rooted in historical adventure and mythological mystery. Yet, their narratives are paper-thin frameworks existing solely to justify tile-matching objectives. Schatz der Azteken frames progression as a quest for artifacts in sunken Aztec temples, while Curse of Montezuma weaves a tale of an explorer cursed by Montezuma’s spirit, and Schatz von El Dorado tasks players with uncovering the lost city’s treasures. These plots are conveyed through brief text menus and static splash screens, with no dialogue, character development, or emotional resonance. Characters are reduced to cursor avatars or silent protagonists, and any “story” is confined to level objectives like “collect 30 jade masks” or “break 20 cursed stones.”

This narrative poverty is deliberate, reflecting the genre’s core appeal: the dopamine rush of pattern recognition supersedes storytelling. The “themes” function as mere cosmetic overlays, replacing gems with Aztec masks, gold coins, or ancient runes. Even the titles lean into colonial-era tropes, exoticizing Mesoamerican and South American civilizations as loot-filled backdrops. While this approach risks cultural insensitivity, it underscores the compilation’s target audience: casual players seeking uncomplicated, meditative repetition rather than narrative depth. The absence of a cohesive narrative highlights the genre’s evolution; later titles like Homescapes (2016) would integrate storylines as progression drivers, but Best of Match 3: Volume 2 prioritizes mechanical purity over narrative ambition.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Best of Match 3: Volume 2 adheres to the genre’s foundational loop: players swap adjacent tiles to align three or more identical items, causing them to vanish and triggering cascading refills. This simple mechanic is executed with competent but unremarkable consistency across all three titles. Each title introduces minor variations—Schatz der Azteken features power-ups like dynamite to clear large sections, while Curse of Montezuma includes timed challenges—but these are cosmetic tweaks rather than innovations. The core systems remain unchanged: no RPG progression, no hybrid combat, no meta-layer beyond level completion.

The UI is functional but dated, favoring pragmatism over polish. Menus clutter the screen with options for difficulty levels and high scores, while tooltips are sparse, assuming player familiarity with genre conventions. The mouse-driven controls are responsive, but the absence of touch optimization (standard in post-2012 mobile titles) dates the experience. Difficulty progression follows a predictable arc: early levels teach mechanics, later stages introduce locked tiles, time limits, or multi-objective challenges. However, balancing issues persist; Curse of Montezuma suffers from erratic difficulty spikes, and power-ups feel tacked-on rather than strategically integrated.

Notably, the compilation excels in accessibility. Its PEGI 3 rating and simple mechanics make it ideal for all ages, while the lack of microtransactions or live-service pressure creates a pressure-free environment. This stands in stark contrast to modern match-3 games, which often monetize frustration with timers or lives. Yet, this accessibility comes at the cost of depth; without RPG elements or intricate puzzles, the gameplay loop risks monotony over extended sessions.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The compilation’s visual direction is defined by thematic palette-swaps, with each game adopting a distinct but equally generic aesthetic. Schatz der Azteken and Schatz von El Dorado employ saturated greens and golds evoking jungles and temples, while Curse of Montezuma leans into ochres and browns to mimic desert ruins. Tile designs are competent but uninspired: Aztec masks, gold coins, and gems are rendered in flat, cartoonish styles with rudimentary animations. Particle effects—such as gem explosions or cascading tiles—are basic, lacking the visceral “crunch” of premium titles like Bejeweled 3. Higher resolutions exacerbate this, with some tilesets appearing stretched or pixelated.

Sound design similarly prioritizes functionality over artistry. MIDI-style soundtracks loop monotonously, while tile clicks and match boops are recycled generic effects. Ambient cues—like temple echoes or jungle sounds—are sparse and feel disconnected from the gameplay. Despite these shortcomings, the compilation creates a cohesive, low-stakes atmosphere. The bright colors and uncomplicated goals foster a zen-like state, ideal for relaxation rather than challenge. This aesthetic uniformity underscores the compilation’s identity as comfort food—visually and aurally unremarkable but reliably soothing.

Reception & Legacy

Launch reception for Best of Match 3: Volume 2 was nonexistent. No critic reviews or player testimonials exist, reflecting its bargain-bin anonymity and niche distribution. Commercial performance likely relied on retail placements in discount stores or supermarket impulse buys, targeting demographics less inclined toward digital storefronts or app culture. Its legacy is similarly muted. By 2010, match-3 compilations were already relics, overshadowed by the rise of mobile platforms and live-service models like Farm Heroes Saga (2012). The genre’s evolution—toward hybridization with RPGs (Puzzle Quest), narrative integration (Homescapes), and aggressive monetization (Candy Crush Saga)—rendered static, offline bundles like Best of Match 3: Volume 2 obsolete.

Yet, the compilation holds historical value as a snapshot of the genre’s pre-mobile era. It documents a phase when match-3 was defined by mechanical purity rather than meta-systems, and when physical media still facilitated genre accessibility. Modern analogues exist in Prime Gaming freebies or indie bundles, but none capture S.A.D. Software’s retail-era pragmatism. For historians, it exemplifies a transitional chapter; for gamers, it offers a monetization-free alternative to contemporary titles, albeit one stripped of innovation or polish.

Conclusion

Best of Match 3: Volume 2 is neither a hidden gem nor a critical failure but a utilitarian artifact of a bygone era. Its three titles deliver competent, if unremarkable, match-3 gameplay, ideal for undemanding players seeking offline, session-based puzzles. The compilation’s strengths lie in its accessibility, lack of predatory monetization, and role as a time capsule of the genre’s foundational mechanics. Its weaknesses—thematic poverty, dated visuals, and balancing issues—highlight the genre’s rapid evolution beyond its origins.

In the pantheon of match-3, this compilation is a respectable B-side—a reminder of the genre’s journey from Shariki’s simple tiles to Candy Crush’s global empire. For modern gamers, its value is niche: a curiosity for completionists or those craving pre-F2P simplicity. For historians, it offers a glimpse into a transitional phase when physical media still shaped casual gaming’s distribution. While it lacks the ambition or polish of contemporaries like Puzzle Quest, Best of Match 3: Volume 2 endures as a harmless, forgettable testament to match-3’s enduring appeal in its purest form.

Final Verdict:★★☆☆☆ (2/5) – A harmless anthology best suited for budget hunters or genre historians, but ultimately overshadowed by its own era’s innovations.