- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: DOS, Windows

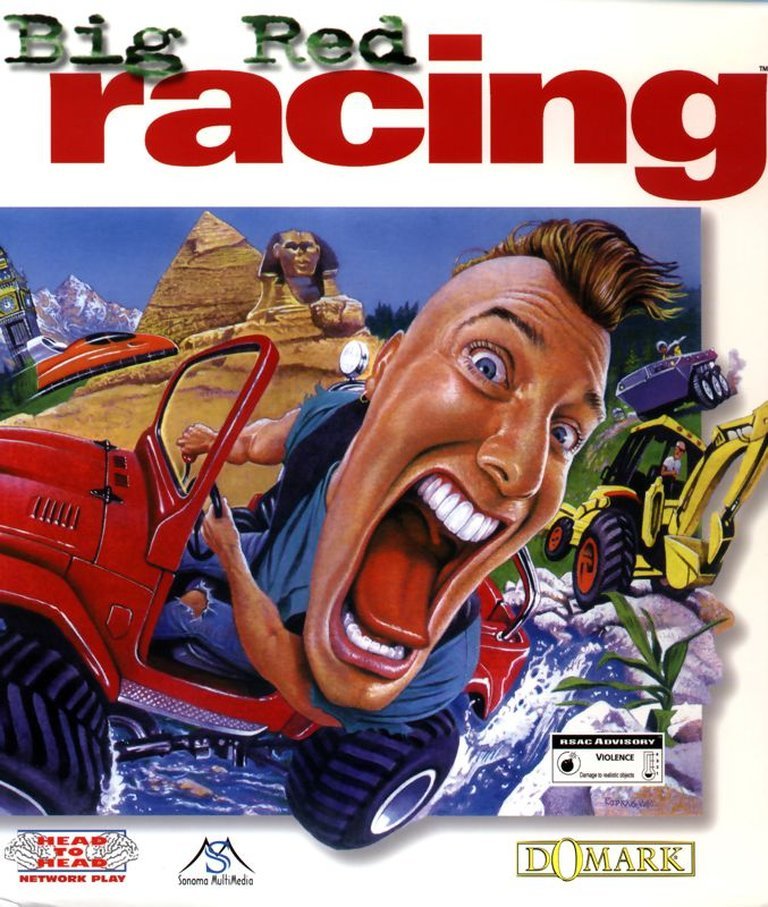

- Publisher: Domark Software Ltd., Eidos Interactive Limited

- Developer: The Big Red Software Company Ltd.

- Genre: Action, Driving, Racing

- Perspective: 1st-person, Behind view

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade Racing, Humorous commentary, Multiple camera angles, Vehicle Customization

- Setting: Dirt, Futuristic sci-fi, Indian, Inner City, Scottish

- Average Score: 63/100

Description

Big Red Racing is an arcade-style racing game that bursts with variety, featuring 16 unconventional vehicles including cars, boats, trucks, spacecraft, and helicopters, racing across 24 circuits set in 7 distinct terrains like dirt tracks, inner-city streets, and futuristic sci-fi worlds. With support for up to six players in split-screen, modem, or network multiplayer, customizable vehicle appearances, multiple camera angles, and a humorous audio commentary, it delivers chaotic, fast-paced off-road mayhem from 1995.

Gameplay Videos

Big Red Racing Free Download

Big Red Racing Patches & Updates

Big Red Racing Reviews & Reception

oldpcgaming.net (63/100): an honest and a no-frills game, an easy one that deserve to be played at least once.

iheartoldgames.wordpress.com (63/100): an honest and a no-frills game, an easy one that deserve to be played at least once.

Big Red Racing: A Nostalgic Gauntlet of Mayhem and Mischief

Introduction: The Unlikely Contender

In the mid-1990s, the PC racing genre was a battlefield of identity. On one side stood the meticulous, physics-obsessed simulations like Papyrus Design Group’s NASCAR and IndyCar titles, demanding respect for their technical fidelity. On the other, the arcade-primed, console-inspired thrills of Need for Speed and Test Drive sought to bring Hollywood-style excitement to the desktop. Into this divided arena stepped Big Red Racing, a game that refused to pick a side. Developed by the appropriately named Big Red Software and published by Domark (later absorbed by Eidos Interactive), it arrived in 1996 with a chaotic, irreverent, and utterly singular vision: a racing game where the point wasn’t realism, but bedlam. Its legacy is not one of critical darling or commercial blockbuster, but of a cult curiosity—a game remembered most vividly for its outrageous vehicle roster, its geographically scattered and often surreal tracks, and its divisive, pun-laden audio commentary. This review will argue that Big Red Racing is a fascinating artifact of its era, a game that perfectly encapsulates the wild, experimental spirit of mid-90s PC gaming, even as its technical shortcomings and uneven design prevent it from achieving true classic status. It is a game less about racing and more about a hilarious, frustrating, and ultimately endearing string of spectacular wrecks across the globe and beyond.

Development History & Context: Born from Last-Minute Lunacy

The game’s development history is as unconventional as its final product. Big Red Software, a UK-based studio, began work on what was initially conceived as a straightforward arcade racer. According to post-release trivia and developer anecdotes, the game was slated for a November 1995 launch. However, in the final months before release, a crucial pivot occurred. As one Swedish review (High Score) famously paraphrased the developers’ mindset: “Ävafan, vi slänger in lite helikoptrar och svävare och… öh… lite båtar också. Det blir nog kul!” (“What the hell, let’s throw in some helicopters and hovercraft and… uh… some boats too. That’ll probably be fun!”).

This late-stage scope creep—adding vehicles like big rigs, boats, and spacecraft—isn’t just a funny anecdote; it’s the game’s defining creative philosophy. It speaks to a development team unshackled from the pursuit of a coherent “sim” or “arcade” label, instead chasing the immediate gratification of novelty. The technological constraints of the era (targeting 486DX/66 systems with 8MB RAM) meant this variety came at a cost. The game employed a simple, chunky 3D engine that, while capable of smooth framerates even in six-player multiplayer (as noted by Next Generation), sacrificed graphical detail and sometimes clarity. The decision to use low-poly models was a pragmatic trade-off for performance and, ironically, became part of its charm—a cartoonish, accessible visual language that avoided the uncanny valley of early 3D attempts at realism.

Further context comes from the game’s written lore. Eurogamer writer Keith Stuart was commissioned to create an extensive backstory for the printed manual—a lavish prop for the game’s bizarre world. In a telling 2016 retrospective, Stuart revealed the publisher cut this material weeks before launch due to cost concerns, a decision he later deemed correct as “indulgent.” The excised lore hints at a deeper, sillier universe that the final game only gestures toward through its track subtitles (parodies of famous films/phrases) and flagrant cultural stereotypes in its commentator voiceovers.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Satire of Stereotype and Spectacle

Big Red Racing possesses a narrative framework so thin it’s almost transparent, yet its thematic execution is aggressively, deliberately loud. There is no plot, no character arc, no protagonist. The player is simply an anonymous entrant in the “Big Red Racing” championship. The “story” is told entirely through the game’s presentation: its track locales, vehicle selection, and, most prominently, its audio commentary.

The game’s primary narrative device is its team of commentators, voiced by industry veterans Lani Minella and Jon St. John. Their schtick is a collection of broad, sometimes cringey, ethnic and national stereotypes tied to each circuit’s setting. Racing in “Scotland” yields commentary dripping with faux-Scottish brogue and bagpipe sound effects. “India” features a commentator with a cartoonish Apu Nahasapeemapetilon-esque accent. This approach is ethically problematic by modern standards, reducing global cultures to a handful of reductive auditory clichés. However, within the context of mid-90s game design, it was a common, lazy shortcut for humor. The game doesn’t seek to critique or explore these stereotypes; it merely exploits them for a cheap, immediate laugh, treating the world as a series of caricatured backdrops for vehicular mayhem.

The tracks themselves are the game’s true narrative stages. They are organized into cups (Continental, Global, etc.) spanning 24 circuits across 7 distinct “terrains”: Dirt, Inner City, Snow, Desert, Alien, and two others. The journey is a whirlwind tour of the geographically absurd. You race monster trucks through the “Australian Outback,” pilot hovercrafts on the “Venusian Lava Flows,” and navigate speedboats through “New Orleans Bayou.” The track subtitles are relentless puns: “An Excellent Adventure” for the USA track, “The Desert of the Real” for a Middle Eastern circuit (a The Matrix reference predating the film by a year). This creates a thematic through-line of satirical pastiche. The game isn’t simulating a global race; it’s assembling a greatest hits of exotic locations and sci-fi tropes into a playable funhouse mirror. The underlying theme is one of unbridled, consequence-free spectacle. The goal is not to honor a locale but to use its most outlandish visual and auditory shorthand to create a memorable, chaotic racing experience. The ultimate expression of this is the inclusion of circuits on the Moon and Mars, where physics are presumably “different” (though the game’s simple engine applies a universal handling model).

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Chaotic Simplicity and Its Discontents

The core gameplay loop of Big Red Racing is deceptively simple: select a vehicle, select a track, race against 5-9 opponents (AI or human), try to finish in the top positions. The complexity and intrigue emerge from the interaction of its vehicle types and track designs, and the significant flaws in its underlying systems.

Vehicle Roster & Handling: The 16 vehicles are the game’s crown jewel, categorized into broad types (Cars, Trucks, Boats, Hovercraft, Helicopters, Spacecraft). Each feels distinct primarily through stat variations in acceleration, top speed, and grip, and through their interaction with terrain. A monster truck bounces wildly over dirt bumps but feels sluggish on tarmac. A hovercraft glides over water and mud but slides uncontrollably on ice. A helicopter… well, it flies, introducing a verticality entirely absent in other vehicles. This creates a fascinating rock-paper-scissors meta where track selection is as crucial as driving skill. However, the handling model across all vehicles is simplistic to a fault. There is no sense of weight transfer, tire deformation, or nuanced braking. Driving is a matter of holding “accelerate” and making gentle steering corrections. This is intentional arcade design, but it borders on unsatisfyingly shallow. As Computer Gaming World brutally noted, the driving model is “sloppy, unresponsive and frustrating.”

Track Design & Progression: The 24 tracks are varied in theme but often follow similar layouts—fewer complex, technical circuits and more wide-open playgrounds with jumps, shortcuts, and environmental hazards (cacti, rocks, spectators). The “Alien” and sci-fi tracks often feature looping corkscrews and transparent tubes, visually striking but mechanically identical to other courses. The game’s structure revolves around “Cups” that must be completed sequentially. Here lies a major design flaw cited by multiple reviews (World Village, GameSpot): the tournament mode requires winning a set number of races at each difficulty (Easy, Intermediate, Expert) to progress, but lacks a save function. A single loss on the “Expert” level, especially near the culmination of a cup, forces a full restart from the beginning of that cup. This is a punitive, archaic design choice that saps motivation and inflates playtime through frustration rather than reward.

Multiplayer: The Saving Grace: This is where Big Red Racing transcends its flaws. Supporting split-screen, modem, IPX/LAN, and even early online services like Mplayer.com, the game was built for social chaos. The simple engine ensured smooth performance with six players. The wild vehicle selection and track variety became a recipe for hilarious, unpredictable, and fiercely competitive sessions. The commentary, which can become irritating in single-player, becomes part of the party atmosphere in multiplayer. As a player review from 2003 reminisced, it was “a favorite back in the Mplayer.com days.” The game understands its strength: it is a socialorbidity simulator, not a racing sim.

UI & Flawed Systems: The user interface is functional but dated. The pre-race vehicle customization (choosing body shape, colors, decals) is superficial but adds a layer of personalization. The real innovation—and occasional hindrance—is the camera system. Multiple angles (chase, close chase, in-car, and rotating external views) are available, but Next Generation criticized the rotating cameras for hindering rather than assisting, as they can disorient during tight maneuvers. The game’s “progressive damage” is another point of contention. Bumping and crashing visibly deform your vehicle and impact handling, but the system is binary and often feels unfair, sending you spinning for a minor tap while AI racers seem impervious—a complaint that fuels the perception of AI “cheating.”

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Garage-Sale Aesthetic

The sensory experience of Big Red Racing is a study in budget-conscious charm and grating annoyance.

Visual Direction: Graphically, the game occupies an awkward middle ground. In SVGA mode (requiring a “very powerful Pentium,” according to a Danish review), textures are sharper and environments more detailed. However, the fundamental 3D engine uses basic, untextured or simply textured polygons. Vehicles are blocky, environments are sparse, and draw distance is short. This “chunky” aesthetic (as Next Generation described it) is not beautiful, but it is clear. The lack of fine detail means the game’s cartoonish intentions are less hindered by technical ugliness than a game striving for photorealism. The art direction’s strength is in its eclectic variety. Jumping from a snow-swept Norwegian fjord to a neon-drenched futuristic cityscape to the surface of Mars provides constant visual novelty, even if each individual locale is rendered with similar simplicity.

Sound Design & The Divisive Commentary: The soundscape is a bifurcated experience. The engine noises, tire screeches, and environmental sounds (splashes, wind) are functional and adequate. The music, described by MobyGames as a “yoof-style soundtrack,” is a collection of generic, upbeat MIDI-rock tracks that fade into the background. The defining audio element—and the game’s most polarizing feature—is the commentary. Delivered with enthusiastic, sometimes strained gusto by Minella and St. John, the lines are a cascade of puns, national stereotypes, and fourth-wall-breaking quips. Lines like “That was a real whoopsie-daisy!” or culturally specific jabs are constant. For some, this is a hilarious, endearing personality (as the 2003 player review attests). For others, it is an “annoying,” “irritating” scourge that cannot be turned off quickly enough (Tomer Gabel’s player review). The commentary is the game’s id given voice: brash, silly, and impossible to ignore. Its inclusion speaks to a development team prioritizing personality and “attitude” over polish or player comfort.

Reception & Legacy: A cult curiosity, not a classic

At launch in 1996, Big Red Racing received a mixed-to-positive critical reception, averaging 77% on MobyGames from 17 critic reviews. The praise consistently focused on its core strengths: overwhelming variety (“so many tracks… so many unusual vehicles” – PC Multimedia & Entertainment), its frenetic, fun-focused arcade nature, and its exceptional multiplayer value for the price (~$30). The FZ Swedish reviews (100%) succinctly captured the pro argument: it’s a “renodlad arkadracer” (pure arcade racer) that delivers “nostalgisk underhållning” (nostalgic entertainment).

The criticisms were equally consistent. The most severe came from Computer Gaming World (40%), which savaged the “sloppy” driving, “confusing graphics,” and “apparent cheating” AI, concluding it could “not be recommended to any age group.” German outlets (PC Action – 55%, Power Play – 67%) were particularly harsh on the dated, “spärliche” (sparse) graphics and “ruckelige Bilderfolgen” (jerky frame sequences). The common thread in negative reviews is a sense that the game lacked the “final polish” (PC Joker)—no replay saves, no proper cutscenes, a barebones tournament structure. It felt like a fantastic concept executed with a budget that ran out before the final 10%.

Commercially, it was likely a modest success, finding its niche among gamers seeking local multiplayer chaos, but it was never a headline-maker. Its legacy is that of a cult favorite and a cautionary tale. It has no direct lineage to modern racers; its spirit of unstructured, vehicle-based chaos is more akin to Ragdoll Kung Fu or the Wii party game Excitebots, but those are spiritual cousins at best. Its true legacy is in the memories of a specific generation of PC gamers who, in the late 90s, gathered around a single monitor, cackling at the commentary as their helicopter crashed into a Martian cliff for the 10th time. The 2000s saw it briefly resurrected on early online services like Mplayer.com, as one player review fondly recalled, before fading into abandonware obscurity. The trivia note about a re-release from Sonoma MultiMedia missing the original CD soundtrack underscores its status as a forgotten asset. It is a game preserved not by its publisher, but by the community’s nostalgia and its availability on retro gaming sites.

Conclusion: A Flawed Gem of Its Time

Big Red Racing is not a great game by any objective standard of game design. Its handling is shallow, its AI can feel unfair, its presentation is rough, and its thematic reliance on stereotypes is a bitter pill. Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to miss the point of its existence. It is a game born from a specific, fleeting moment in development where “more is more” overcame “better is better.” Itis a game that understood, in its core DNA, that video games can be silly, disposable, and purely, joyfully fun.

Its place in history is not as a pioneer of mechanics or narrative, but as a pure artifact of 1990s PC game culture. It represents the era’s optimism about 3D graphics, its often cringe-worthy but earnest attempts at “attitude,” and its focus on local multiplayer as the social hub of gaming. The fact that its most glowing modern review comes from 2012 (Retro Spirit)—”I can recommend Big Red Racing in the warmest way, 17 years after it first saw the light of day”—speaks volumes. It is remembered not for its perfection, but for its character. The thrill of finally mastering a boat on a tricky river course, the laughter induced by a commentator’s terrible pun as you win a race, the simple joy of six-player split-screen chaos—these are the visceral memories it evokes.

For the historian, Big Red Racing is a perfect case study in the trade-offs of development: variety versus polish, humor versus sensitivity, ambition versus execution. For the nostalgic player, it’s a time capsule to an era where a racing game could include a helicopter and a Martian circuit without a second thought. It is, ultimately, a game that is perfectly, defiantly itself—flaws, foolishness, and all. It earns its 7.4 MobyScore not through merit, but through sheer, unadulterated presence. It is the loud, brash, slightly broken uncle of the racing genre, and we’re glad he showed up to the party.