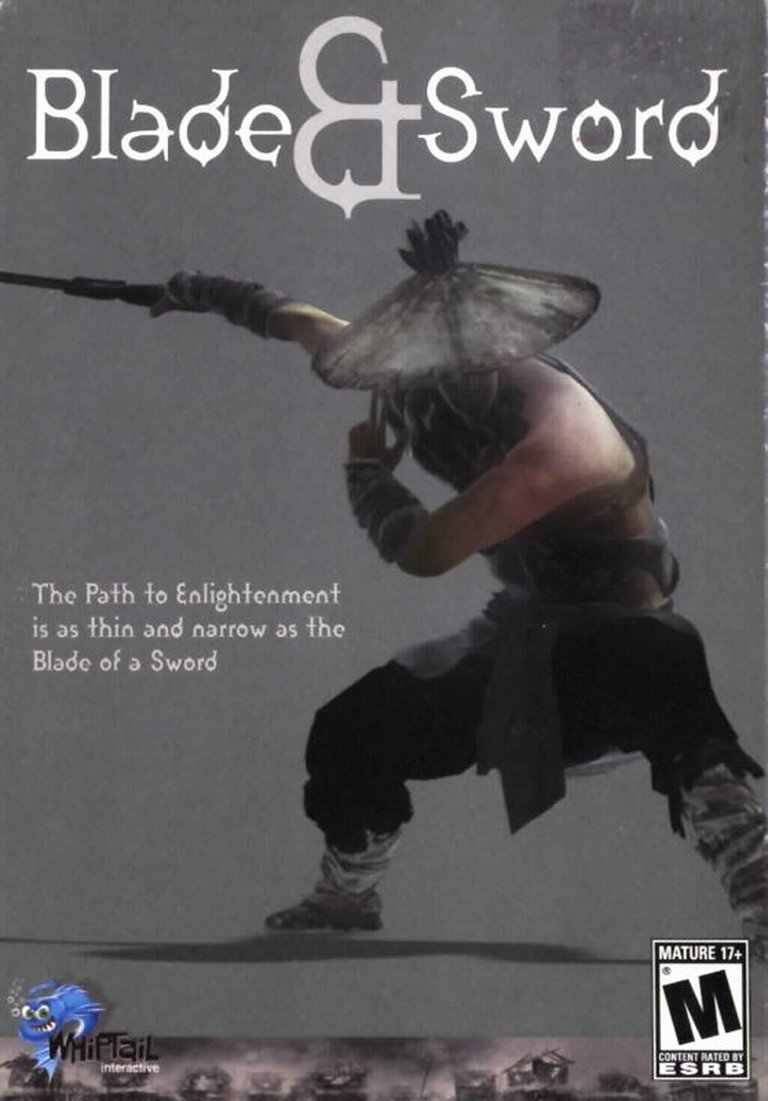

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Akella, Beijing Happy Entertainment Technology, Centent Interactive Co., Ltd., Kogado Studio, Inc., Whiptail Interactive

- Developer: Boya Studio, Pixel Studio Co., Ltd.

- Genre: Action RPG, Role-playing (RPG)

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Action RPG, Blocking, Custom combo moves, Dodging, Kung Fu combat, Mouse gestures, Skill tree system, Super attack

- Setting: China (Ancient, Fantasy, Imperial), Martial arts

- Average Score: 52/100

Description

In the ancient Chinese setting of Blade & Sword, players are thrust into a world torn apart by Emperor Jo’s fall in 1044 BC, whose dying curse—fueled by hatred—unleashes a rift between the human, beast, and demon realms. As monstrous armies storm through, courtesy of the treasonous grand wizard Wen, it’s up to the player to battle across these realms and restore peace. Inspired by Diablo’s action RPG mechanics, the game lets you choose from three martial heroes, each trained in 12 unique Kung Fu styles with gesture-activated super moves. Rendered in isometric view with point-and-click gameplay, Blade & Sword blends intense melee combat with combo crafting, delivering a fantasy-rich, demon-slaying adventure.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Blade & Sword

PC

Blade & Sword Free Download

Patches & Updates

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (53/100): Blade & Sword has style. Style enough to make up for the shortcomings of completely unoriginal mechanics, style enough to compensate for the excessive difficulty and style in such quantities to make other developers turn green with envy.

ign.com : Beyond being a 2D, sprite-based, isometric clickfest, Blade & Sword also chooses to incorporate the Horadric cube (here referred to as a “Spyragic cube”), town portal stones you can activate along the way, town scrolls, (called “homing portals”), a village with a healer who will refill your mana and health for free (a red meter and blue meter), socketed weapons, 800×600 max resolution, and a rather similar skill point system.

mobygames.com (50/100): Average score: 50% (based on 17 ratings)

gamefaqs.gamespot.com : A mediocre game for a cheap price!

metacritic.com (53/100): Blade & Sword has style. Style enough to make up for the shortcomings of completely unoriginal mechanics, style enough to compensate for the excessive difficulty and style in such quantities to make other developers turn green with envy.

Blade & Sword: Review

Introduction: Forgotten Martial Arts ARPG in the Shadow of Diablo

Emerging in 2002-2003 from Beijing-based Pixel Studio, Blade & Sword (刀剑封魔录, Dao Jian Feng Mo Lu) entered an overcrowded action RPG (ARPG) market dominated by Blizzard’s Diablo II. While lauded in some quarters for its unique attempts at integrating East Asian martial arts combat systems within a classic Diablo-inspired structure, the game flickered briefly in the gaming zeitgeist before lapsed into obscurity. The game’s contemporaneous reception was polarized and, at times, demoralizing. On the one hand, its customizable combo engines, ancient Chinese setting, and innovative gesture-based “Super Attacks” offered technical and aesthetic novelty in an genre fixated on Western fantasy tropes. On the other hand, the game’s laughably rudimentary asset production, translation errors, rigid save system, and utter lack of progression variety (specifically, no loot-based weapon or armor changes) led to some of the harshest blistering of any console or PC game of the era.

This in-depth analysis reframes Blade & Sword as a complex tragedy of ambition, technical feasibility, and unforeseen cultural/industry shifts. The game is ultimately shackled by its era of origin—the pre-3.0 indie scene where PC publishers (Whiptail Interactive, Kogado Studio, Akella) sought replicable formulas but the developers’ true ambition mashed Street Fighter combo logic, Kung Fu thematic stylization, Diablo 2 point-click simplicity, and Chibi-Robo!-lite quirky gem crafting into one haphazard, often incoherent, but fascinating mess. At its core, Blade & Sword asks whether creators can transcend the “Diablo clone” premise by radically rethinking facets of ARPG gameplay mechanics—and ultimately demonstrates how a lack of cohesion in design, combined with limitations of game scope, can doom even the best-laid plans.

My thesis: Blade & Sword is a textbook case of unfulfilled potential and broken synergy. Its core premise – of action-style martial arts ARPGing – is ingenious and ahead of its time. The group had the vision for a unique product but lacked technical, financial, or analytical bandwidth to implement this vision coherently, resulting in a fusion of great mechanics that clash on a holistic scale. This game is the story of a nascent, daring Chinese studio attempting to break into Western markets using old tools and fresh ideas—and demonstrating exactly how fast those tools can fail when the idea is too big. It is a cult all-time if you are willing sacrifice modern polish for shaky, unfinished brilliance.

Development History & Context: The Rise of Pixel Studio in the Asian Action-RPG Scene

Founding & Origins – Boya, Pixel, and the “Prince of Qin” Legacy

Developed jointly by Pixel Studio Co., Ltd. and Boya Studio, Blade & Sword was born at a watershed moment in the East Asian ARPG market. The two studios were linked to a prior historical RPG, Prince of Qin (Qin Wang, 2002), which suffered from severe physical distribution issues in the West and budget microtransaction-style micro-releases but was otherwise praised for its authentic recreation of the Qin dynasty setting and its ambitious attempt to blend Western RPG tropes with “period-appropriate” character progression (see: Old PC Gaming’s retrospective). The Blade & Sword project was thus both an opportunity for the devs to achieve Western recognition and a means of using proven mechanics (the Diablo-style UI, item tracking, crafting) to ground what was otherwise a radical melee combat experiment.

Market Context – An Age of “Diablo Clones” and the Search for Innovation (2000-2003)

In the early 2000s, Blizzard had not yet released Diablo 2 1.10 (2003: the balance patch that added the Horadric Cube upgrades) or WoW (2004), but the ARPG “modification” scene was exploding. Titles like Diablo: Flame (Russia), Those Who Walk, Rentrack: Armageddon (USA), and the modded versions of Heroes of Might & Magic 3 and Anno 1503 were all pushing the boundaries of isometric click RPGs. Diablo II had defined the format, and every developer sought to replicate its intangible “formula” while inserting their own twist. Most simply refocused the setting (Arcanum), added 3D (Dungeon Siege), or expanded skill trees (Sacred). Pixel Studio, however, attempted to fundamentally redesign how players interact with ARPG combos.

Resources, Red Tape, & Eastern Markets – The Legacies of Obsolescence

Blade & Sword was released at a pivotal digital transition point: the early broadband era, when CDs were still dominant but full installations were beginning to spook customers (per GameFAQs Ryougeh, who reports a 1.4gB install shock for a game on modest spec machines). The game’s 25-people credits (19 actual developers) paints a picture of a studio working at a frenetic, distributed pace, with art assets likely being farmed out to freelance illustrators and the core combat system and UI being in the hands of two key figures: Yan Liu (Programmer, Tech Director) and Kun Liu (Art Director, Lead Programmer). These two, both cores of the Prince of Qin effort, were struggling against:

- Hardware Limitations: Max resolution of 800×600 (a 1997 sticky point), a full install, but optimized for K6-2 350 MHz (very old DOS box)

- Software Dead End: Sprite-based 2D, not real-time 3D, largely unskippable text with no VA.

- Publishing Pressures: Sold in North America and Eastern Europe (Poland, Russia), but with no explicit localization team (LED to massive translation errors reported in every MetaCritic and GameSpot review).

- The Emerging Indie Scene: A PC market that was beginning to judge “polish”, but rewarding big publishers and franchise sequels. This would be the last gasp for the type of deep, meta ARPG culture before the arrival of more robust, automated online attack cutscenes in 2010s titles (Titan Quest, Grim Dawn, Path of Exile).

**Legacy and “the Lost PC”

The game’s situation was not merely technical; it was cultural. The game was released in early 2004 but advertised at the tail end of Diablo 2’s phenomenon (with Terror’s Realm for Europe in 2006; a musofcity peak in 2003). By the time Blade & Sword reached Europe and North America, the Diablo II audience had already pivoted toward World of Warcraft. This **market timing (see: GameOver Online’s scathing 50% review: “I decided I was wasting my time after halfway”) was perhaps more damaging than any technical flaw.

The developers also missed the possibility of localization polish: the game’s launch featured no ink or paper manual (GameFAQs complains of the need to print the 55-page pdf), no voice acting, and bad grammar and misspellings (Per IGN: “the thread of what’s going on” might be lost, per MetaCritic aggregate 53). This pointed to a development process where the visuals and mechanics were given priority over cultural accessibility in the West.

The 140 Hour Illusion – Factory-Set Diffusion vs. True Challenge

GameSpy’s critique of the 140-hour gameplay ad as being ‘watching-the-paint-dry’ monotony is telling. The lack of any sort of replay value outside of permadeath/respawn + save-exit system means that any claim to playtime is based on artificially drawn-out leveling and respawn frustration—not actual fun. The game’s lack of multiplayer, randomized maps, or meaningful plot diversions meant that the “140 hours” was a factory-mandated ploy to compete with battle.net meticism, not a legitimate design pillar. This betrays a developer who sensed the market was demanding beefier games but didn’t know (or couldn’t implement) the tools to achieve it beyond padding.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive – Fatalism, Displacement, and Lost Heritage

Emperor Jo’s Suicide: A Cosmic Hubris

The game opens with a tragedy of scale: Emperor Jo, facing defeat in 1044 BC, lights his palace on fire to fuel a cursed last gasp of hatred. Grand Wizard Wen exploits this death to open a rift between the Human, Beast, and Demon Realms, unleashing monsters and controlling them, thus creating a campaign for the player to traverse the three realms to defeat both Jo (now a demon warlord?) and Wen.

This allows Blade & Sword to present a multi-realm cosmology (an idea more fully realized in Titan Quest 2 years later) but undercuts it with narrative sparsity and mystification. The planar rift concept, though novel in the early 2000s for any non-rom-God ARPG, is poorly explained. Game enemies drip monsters like a dark fantasy Total War modded map, with no in-universe link beyond “Wen did it”. The Elemental Realms feel less like dark eldritch planes and more like environmental backdrops—ghost villages, poison swamps, volcanic hives—reused liberally.

The Quest for the Refuge, the Refugees

The NPC interactions (30+ in 40 levels) are where the game tries to weave in a theme of displacement and fragmented time. Wen’s rift not only lets in creatures but snaps time, bringing warriors, sages, even a ghost couple, from various periods of Chinese history into one era. The player is asked to mediate many NPC disputes, deliver letters, and reunite souls. This ancient history “mashup” concept has echoes of the Rasetsu Fumaden or Touken Ranbu Online lore, which builds stories around “time-traveling warriors”, but here it’s relegated to side quests and fetch tasks, not the core narrative.

The ghost couple quest is particularly eerie: the husband’s ghost is trapped near the village; the wife’s ghost is discovered in a later level; the final reunion requires carrying a spoofing item (a “Soul Amulet”) to bridge distances. It’s a chilling reflection of the emotional turmoil of death and spatial separation. The fact that ghosts can write and open containers but can’t move beyond their designated location is a brilliant example of magically unescapable fate—they are trapped by the rift’s rules.

This contrasts with Wen’s power, which is the power to control the rules—to shift realms, to enslave demons, to bind a dead emperor to a corpse. The level of asymmetry in power —ghosts with residual agency, Wen with total agency— suggests a central theme: horizontality of fate vs verticality of power. The player character, the “hero”, is the only force who can move freely between planes, who can alter the rules through combat. This makes the player not just a warrior, but an agent of resolution in a universe defined by displacement.

The Absence of Dialogue Trees, Emotional Dissonance, and the Tyranny of Text

Despite this bold thematic premise, the game fails to leverage these ideas beyond monochromic objectives. There are no dialogue trees, no responses, no real deviation from the “deliver X, kill Y” structure. This turns the player into another agent of the system—not a player shaping the story, but a janitor cleaning up Wen’s mess.

This absence reifies a broader issue: the text-scrolling prison. Every communication is a long, grindy roll of text (no animation, no speed-up). Compare this to even Diablo 1’s use of voiceovers in cutscenes (I am not now alive…). The lack of animation and auditory feedback for NPCs makes them feel like cogs in a machine, their emotional complexity reduced to static icons. The brilliant idea of ghosts with longing, refugees with homes lost—are all silenced by the game’s inability to deliver their stories with motion, emotion, and timing. It’s a narrative tragedy: a premise with deep potential, made banal by technological and artistic limits.

Translation, Manchurian Déjà Vu, and Text Corruption

The aforementioned translation errors (from Mandarin to English via what appears to be literal machine tools or a very rudimentary third-party service) undermine the player’s connection to the setting. The Asian names are rendered inconsistently (Wen appears as Wen, Wen, and “Wen the Grand Sorcerer”), and some item descriptions have text corruption (“Rare Candy” descriptions repeat the same paragraph three times). The end result is a game where the language feels alien, not foreign—not exotic, but broken. The setting is ancient China, but the text feels like a Ph.D. student’s rough translation of a folk tale, not a fully curated experience.

This is not just a technical shortcoming; it’s a cultural failure. The game sought to offer a Chinese take on the ARPG, but allowed the very language to become a barrier to entry. It’s not just that the translation is poor; it’s that the game doesn’t respect its own foreign setting by investing in the tools to make it accessible.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Combo Paradox – Ambition Undone by Implosion

The “Click RPG” Skeleton – The Usual Suspects with Chinese Names

At its base, Blade & Sword is a horizontal-down isometric click-that-guy game. Movement is point-and-click with shift for sprint, alt for block, space for dodge. Health and “Chi” (mana) regenerate. Gems are socketed. Town is a hub. Portals and scrolls exist (known as “home stone” and “teleport stone”). The Horadric Cube, the game’s most famous unoriginal element, is here as the Spagyric Cube—a direct homage that showcases how Pixel Studio was so close, yet so far. The Cube allows three-tiered crafting of gems (7 types x 3 pure) and crazy compound gems, but its real function is to highlight a key structural rift: no lootable gear.

The Fateful Weapon Independence – The Biggest Skeleton in the Closet

This is the simplest but most devastating mechanic in the entire game. All three player characters have:

- No change in core weapon or armor during the 140-hour campaign. (No new swords armor or weapons are never looted or collected from enemies. This is a reoccurring motif in reviews: “shiny swords, cool-looking armor and fancy rings are the staple of this genre, and they are pretty much non-existent” [GameDaily], “The lack of any new armor or weapons is really a serious deterrent … the RPG system is very simplified” [Gamer’s Hell])

- Their combat power is derived entirely from gem-socketting and leveling, not equipment. This means, by 10 hours in, the player’s only tangible progression system is refining gem formulas and practicing combos.

- Their “tactics” are limited to blocking, dodging, and combo-mashing – not to switching gear or tools.

This fetish of static gear is the game’s unintentional thesis statement. It says: “We know the ARPG genre is about loot porn, but we want it to be about technique.” This is not inherently bad. Games like Darksiders or Dark Souls later succeeded in “one-weapon challenges” by giving players meaningful subsystems (weapon art, shader combos, magic) to compensate. Blade & Sword, though, offers only gems and skill trees.

The Combo System – Four Unique Lights in a Tunnel of Boredom

The combo mechanic is the game’s invention. Each character has 12 unique Kung-Fu attacks and 4 Super Attacks (drawn with mouse gesture). The player can chain attacks in combos of up to 5-7 moves (see: Old PC Gaming’s review: “encouraging a careful ordering of attacks”). This lets the brawler use a “punch-upkick-kick-fistpunch-groundsmash” string, the nimble go “blade-cut-turn-teleport-stab-backflipdart”, etc.

When combined with stamina-blocking (alt) and dodge-slips (space, which teleports to 4 nearby points), the game attempts to function as a 2D action fighter. The knock-back mechanic is the pivot: enemies are knocked down after a few hits, becoming vulnerable while prone, but cannot be attacked. This creates a hit-and-run rhythm; combo → knock down → retreat → re-engage. This should be the core loop of a martial arts ARPG: *fluid, stance-driven, combo-centric*—but it fails because:

- It’s blended with Diablo-style damage sponge enemies. Most mooks take 5-10+ minutes to kill, requiring 3+ full health potion runs to the town (because you can’t save inside levels). The knock-down window is short, and enemies have insane hit points.

- The combo attacks slow the player. Each skill strike uses a significant Chi resource. For the first 5-7 hours, Chi regenerates so slowly (under 50% regen/km) that using a combo three times drains the player.

- The damage output is low. A combo that should kill a minor zombie takes two-three cycles. This makes the game a chore, not a rush.

- AI swings wildly. Some mobs have pack behavior, but most have AI that just turns and runs randomly (Per TVTropes: “Artificial Stupidity”). This makes attempting a fancy 7-hit combo pointless when the enemy just phases out.

The combo system is thus a paradigm of unfulfilled potential. It’s a feature that could have defined the game (imagine a pixel, combo-centric ARPG in the style of Streets of Rage and Diablo), but it’s sunk by its context—slow combat, high enemy health, low regeneration, and bad AI. The combo is a light in a tunnel of hack-n-slash boredom.

The Save System – Refuse to Die Feels Like Punishment, Not Progress

The game has no in-level save. The save point is the only point where you can exit the game. When you save, you quit to the menu, re-enter the game, and are spawned in the nearest village. All killed enemies respawn.

This is not just inconvenient; it’s antithetical to action RPG design. Compare this to:

- Diablo 2: Restart, monsters are gone, new areas are open.

- Action Trip: Save checkpoints are given in zones.

- Many final-hour PC ARPGs: Allow auto-save.

Blade & Sword instead uses save scumming prevention to artificially extend playtime. The result is a save system that only exists to block fun, not to enable it. The Player (per GameFAQs) resorts to “only saving at teleporters and hoping the game doesn’t crash.” This system is so dysfunctional it damages the whole experience, making gem experiments (see below) frustrating, boss fights tedious, and exploration risky.

Gem Crafting – The Heroic Unpolished System

The Spagyric Cube and gem-crafting system are the game’s sole true innovation. Players can combine gems to refine (basic → pure) and compound (fire + ice + wind = explosion gem). Gems are socketed into weapons and armor (max of 6 in the weapon, 6 in the armor). This allows a player to build a character around fire AoE chaos, Chi-stealing siphon, or stealth-refines. This system allows for deep customization, and per Peeto (Metacritic user), 200+ hours of fun can be had perfecting gems.

But the system is hobbled by:

- The Save Scumming Prevention mentioned above: If you craft a bad compound gem, you cannot reload. You must use it or go through a long quest to remove it.

- The scarcity of gems. Gems are rare, and the refinement process is fiddly. The manual (in the PDF) acknowledges the fiddliness but offers no advice.

- The lack of feedback. There is no stats-increase animation or particle effect when a gem is socketed. The visual reward is minimal.

This is the irony: a system that could be the game’s saving grace (deep, long-term customization) is under-polished and poorly integrated into the core loop.

Super Attacks – Street Fighter in a 2D ARPG

The ability to perform “Super Attacks” via mouse gesture drawing (circle, lightning, shield, square) is the game’s boldest faux-fighter move. These attacks use all Chi and heal all health, but take 30-60 seconds to recharge. They are used to clear crowds, heal, or put a boss into a vulnerable state.

But their real function is to create comic relief in a grindy game. They do not, however, fix the core damage sponge problem.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Setting Trapped in 1997

The Visual Paralysis – 800×600 and the Fear of 3D

Blade & Sword’s art is its most outdated feature. The 800×600 max resolution, 2.5D isometric engine, and sprite-based combat make it look like Dungeon Raid (2000) or Age of Empires II (1999). Character animations are “stiff” (GameFAQs) with minimal attack frames (2-3 per combo strike), and spell effects are minimalist (see: GameSpot’s “slightly cheesy spell effects”).

The backgrounds are detailed for their time – snow leaves footprints, fish swim, weather cycles, and day/night. The theme, though, is not just ancient China but ancient China as conceived by a 1990s American video game. Villages have fashionably arranged pagodas, temples, and ponds. Demon Realms look like dark theme park Attractions — fire-and-brimstone stages, not Erebus.

Day/Night, Weather, and the Illusion of Interaction

The game has a dynamic weather system (snow, rain, sun) and day/night cycle, but these do not affect gameplay. Monsters respawn at night. No quests are at day-only locations. No events shift. This is atmosphere over environment—a world that looks alive but acts static. Compare this to Dark Souls 2011’s weather winds influencing magic damage, or Zelda: Breath of the Wild’s weather physics. Blade & Sword has weather, but not interactivity.

The Sound Design – Pipes, Drums, and the Shouting Man

The music is consistently praised (see GameFAQs: “the music in Blade & Sword is great”) as fitting the ancient Chinese theme. The instrumentation – guzhong for attack, erhu for sorrow, drums for combat – is well-executed. However, tracks are short (“ringing false after 5 minutes,” per GameFAQs).

Sound effects are inconsistent. Footsteps are good. Impact sounds are repetitive. Voice effects – the player character’s occasional “aaaa!” – are overly loud and frequent (IGN: “I had to turn the volume down to a whisper”). The Monster sounds (growls, shrieks) are generic.

The absence of voice acting means the only voices are the player’s own shouts and the ambient music. This contributes to the feeling of isolation—a game where combat feels personal but story feels alien.

The “Artificial” World – No Une Earthly Design

The world is not realistic. Very few games in 2003-2004 attempted realistic simulation (compare to Oblivion in 2006). Here, the world is static, self-contained, and not modular. Areas are small, with invisible walls. The “Beast Realm” does not have a unique, biologized ecosystem. The lack of verticality (jumps, ladders, flying) makes the world feel flat, like a diorama.

The itemization — the sprite representation of gems, money, potions — is utilitarian. The “Jin coins” of the game are a good design, but the main weapons and armor are not visible to other players or NPCs. The world feels like a game, not a living ecosystem.

The visual “ping” of combat — the blood and gore, the splinters and smoke — is minimal. This makes the high difficulty feel unfair—the player has no sensory feedback to justify a 10-minute boss fight.

Reception & Legacy: The Game That Beat Itself to Death

The Critical Verdict – 50% average, 17 ratings, 320+ words of pain

At 50% on Metacritic and 3.1/5 on players, Blade & Sword is the textbook case of “mixed or neutral.” No 10/10 sweep. No 9/10 “underrated” reevaluation. The reviews are long, detailed, and uniformly painful.

Key criticisms:

- Over-reliance on Diablo tropes: 13/17 reviews note it’s a “clone” or “mod.” “… style only fun for so long before it becomes ‘fun’.” [IGN] “…plays like a mod rather than something built from the ground up.” [ActionTrip]

- Terrible save/respawn: 11/17 reviews mention it’s frustrating. “Had to fight my way back to my pre-save position.” [GameFAQs]

- Lack of loot and gear variety: 9/17. “Shiny swords, cool-looking armor … non-existent.” [GameDaily]

- High difficulty: 8/17. “Boss takes 5-10 minutes … a time-padding feature.” [IGN] “Brutal hard minibosses.” [GameFAQs]

- Outdated graphics/audio: 8/17. “Looks like 1997.” [GameCritics] “Must be rewritten, not translated.” [MetaCritic]

Praise is reserved for:

- Combo system: 7/17. “An honest-to-God good idea.” [CGW] “One of the best ARPGs of all time.” [Peeto, Metacritic]

- Music/sound theme: 4/17.

- Price ($29.99 at launch): 3/17. “Decent for the price.” [Ryougeh, GameFAQs]

The Player Reckoning – A Cult of Combo Saints

The player review score of 3.1/5 masks a rabid, cult-like following for the combo system. On Metacritic, Peeto and Dui (9/10, 9/10, 2012/2012) sing its praises: “200+ hours of amazing gameplay”, “Shame they don’t make games like this anymore.” DreamStation.cc and others note its “Diablo fans but with Kung Fu” appeal.

Now on Steam, with a modern controller patch, it’s become a cult niche title among fans of Diablo 2Hordes, Rasetsu Fumaden, and Black Myth: Wukong. Its combo system is directly cited in fan reactions: “Reminds me of Wukong’s staff spins.”

Influence – The Game That Made the Cut in 2004, the Forgotten Gem

Blade & Sword is not a direct influence on major games. Diablo 2, WoW, and Pillars of Eternity developed their own loot systems. Titan Quest (2006) copied the realm-jumping idea. Path of Exile (2013) kept the gem-crafting, but made it random.

But consider: Black Myth: Wukong (2024) has exactly three weapon types (staff, sword, firecracker), combo chaining, boss fights, and spirit refines. The visual is 4K, but the gameplay loop is Blade & Sword with better tools.

The Japanese* Touken Ranbu series (2015+) also uses no random loot; instead, characters have “personality” upgrades. The **core concept of static gear + combat prestige is echoed here.

Blade & Sword thus presents a precedent for a “not loot, but style” ARPG. It’s not remembered as a horror show (like Daikatana, 2000), nor a classic (like Arcanum), but as a curiosity. The industry didn’t learn from it; it side-stepped it, using newer tech to fix the flaws. The idea survived, but the game did not.

The “Legend” of the Lost Sequel

Blade & Sword 2: Ancient Legend (2003) tried to fix the flaws — added loot, smoother animation, better UI — but followed the same format. It didn’t sell. The Pixel Studio “legend” of what could have been is now a footnote in Chinese gaming history.

Conclusion: A Revolt Against Loot Porn, and the Prison of Its Own Corpses

Blade & Sword is a revolution in ARPG design that failed. It dared to say the ARPG didn’t have to be about shiny swords and cool rings — it could be about combat technique, gem refinement, and environmental traversal.

The game’s ambition — to be Kung Fu ARPG, not Diablo with Chinese costumes — was correct and ahead of its time. The combo system, gem crafting, and multi-realm concept were innovations that could have defined a new sub-genre. Yet, the game implodes under the weight of its own broken synergy:

- The combo system requires fast, responsive combat, but the game is slow, damage-sponge-heavy.

- The gem crafting requires deep experimentation, but the save system blocks load/stash testing.

- The setting has strong atmosphere, but the AI and enemies feel artificial.

- The music is great, but the text is unreadable.

This leads to a failed rebellion. The game rebels against the ARPG’s obsession with loot, but replaces it not with style or flavor, but with grind. The true legacy of Blade & Sword is not that it introduced new mechanics, but that it showed how close a game can come to genius, and still feel like death.

Its place in video game history is not as a failure, nor as a classic, but as a warning: vision alone is not enough; the tools, the timing, and the polish must also be there. Blade & Sword is the ARPG’s Heart of Gold — a game so ambitious, so unusual, so stuck in the wrong era, that it is both a tragedy and a guidepost.

If you can look past the clumsy saves, the spam, the old engine, the broken grammar, and see only the **combo, the gem, the gem