- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Gizmondo, GP2X, Symbian, Windows Mobile, Windows

- Publisher: Elements Interactive B.V.

- Developer: Elements Interactive B.V.

- Genre: Action, Scrolling shoot ’em up

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Automatically generated levels, Shooter, Weapon Upgrades

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 75/100

Description

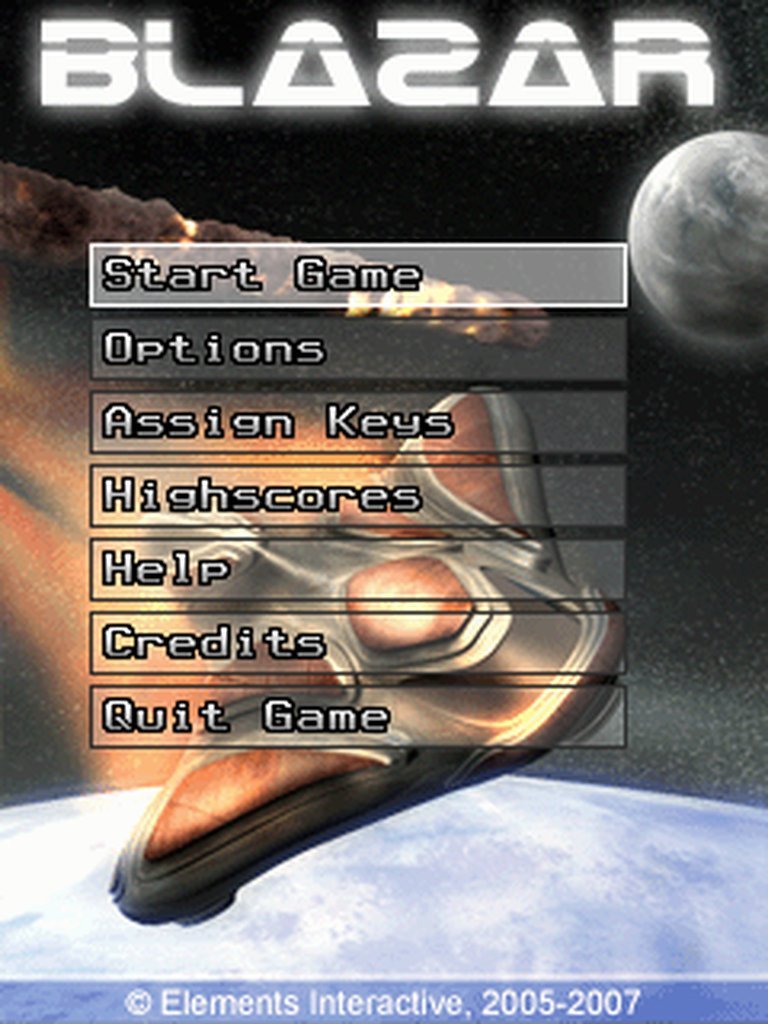

Blazar is a sci-fi horizontal scrolling shoot ’em up where players pilot a spaceship through procedurally generated levels. Set in a futuristic universe, the game features three upgradeable weapons—rocket, spreader, and charger—with customizable attributes like range and spread. Developed by Elements Interactive B.V. and released across multiple platforms from 2005 to 2007, the game offers classic side-view action reminiscent of retro space shooters, emphasizing high-score chasing and intense boss battles.

Blazar Reviews & Reception

allaboutsymbian.com (73/100): However, the graphics are also extremely bland-looking, with backgrounds that are all grey and brown, and not much in the way of texture or detail.

Blazar Cheats & Codes

Blazer Drive (Nintendo DS)

Use the following codes at the password system:

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| rema hebo mesa mage noe yane | Unlock Kandatsu (Legend Mysticker) |

| waga sani giri miku nuu seni | Unlock Don Quixote (Rare Wind Boost Mysticker) |

| hichi egu ogo zare tozo zani | Unlock Solomon (Rare Boost Mysticker) |

Blazar: A Forgotten Gem of Mobile Shoot ‘Em Ups

Introduction

In the mid-2000s, as gaming giants like Resident Evil 4 and God of War redefined AAA expectations, a small Dutch studio, Elements Interactive, quietly released Blazar—a horizontal scrolling shoot ’em up that embodied the spirit of arcade classics while embracing emerging mobile platforms. Though overshadowed by blockbusters, Blazar carved a niche as a portable homage to Gradius and R-Type, blending procedural generation with retro aesthetics. This review argues that Blazar is a fascinating artifact of its era: a technically ambitious but flawed experiment that foreshadowed indie gaming’s embrace of procedural design and bite-sized play sessions.

Development History & Context

Studio Vision & Technological Constraints

Developed by Netherlands-based Elements Interactive B.V., Blazar was part of a wave of early mobile titles leveraging the Symbian and Windows Mobile ecosystems. The studio, known for puzzle games like Quartz 2 and S-Tris, aimed to adapt the shoot ’em up genre for handheld devices using their proprietary EDGELIB engine. Released in 2005, Blazar targeted an era dominated by Nokia N-Gage and the nascent Nintendo DS, where hardware limitations demanded simplicity. The game’s 2D-scrolling design was pragmatic, sidestepping the 3D ambitions of consoles to prioritize smooth performance on weaker CPUs.

The 2005 Gaming Landscape

2005 was a watershed year: the Xbox 360 launched, Shadow of the Colossus redefined art games, and Guitar Hero birthed a new genre. Mobile gaming, however, was still in its infancy. Blazar’s auto-generated levels and compact design catered to on-the-go play, but its release across Symbian, Windows Mobile, and Gizmondo—a short-lived handheld—reflected the fragmented market. Critics praised its ambition but questioned its place in a world increasingly focused on narrative depth and 3D immersion.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot & Characters

Blazar’s narrative is minimalist: players pilot a lone spacecraft against an endless alien onslaught. There’s no dialogue or named characters—only survival. Backstory is implied through environmental cues: derelict ships, alien hive structures, and fragmented UI text hint at a galaxy-wide collapse.

Themes: Humanity vs. Automation

The game’s procedural generation and escalating difficulty evoke existential futility. Enemies grow smarter, levels twist unpredictably, and power-ups feel like fleeting respites. A subtle theme emerges: the pilot’s struggle against an impersonal, algorithmic universe. The Symbian version’s radar—a glowing grid tracking threats—frames the player as a cog in a mechanistic war, echoing Battlestar Galactica’s man-vs-machine dread.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop & Combat

Blazar’s gameplay is deceptively simple:

– Weapons: Three types—rocket (single-target), spreader (wide arc), charger (beam)—can be upgraded for range or damage.

– Procedural Levels: Each playthrough generates new enemy placements and terrain, though repetition sets in after boss fights.

– Bosses: Screen-filling foes with pattern-based attacks (e.g., rotating laser grids, spawner drones).

Innovations & Flaws

– Radar System: A top-down minimap previews threats, a novel feature for mobile shooters.

– Janky Controls: Critics noted awkward touchscreen/d-pad integration, especially on Symbian.

– Repetition: Auto-generation often recycled enemy clusters, diluting long-term appeal.

UI & Progression

The HUD is utilitarian: shield/health bars, score counter, and weapon icons. Lack of a meta-progression system (e.g., permanent upgrades) limits replayability, relying solely on high-score chasing.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design

Blazar’s pre-rendered spritework blends chunky Amiga-era aesthetics with subtle modernity:

– Enemies: Bio-mechanical hybrids reminiscent of Alien’s Xenomorphs.

– Environments: Grungy asteroids, neon-lit space stations, and pulsating organic tunnels.

Critics split on its visuals: All About Symbian called them “bland,” while s60.at praised the “retro charm.”

Sound Design

The soundtrack—a pulsing electronic score by DJ PWB—echoes Daft Punk’s Tron: Legacy, but repetitive weapon SFX grated. The Gizmondo version’s rumble feature added tactile feedback, a rare luxury for 2005 mobile titles.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Reception

Blazar earned a 78% average from critics:

– Praise: “Pure, stress-relieving fun” (s60.at, 100%).

– Criticism: “Repetitive and visually dated” (XS Magazine, 60%).

Commercial Performance & Influence

The game sold modestly, buoyed by Symbian’s install base but hampered by platform fragmentation. Its legacy lies in procedural design: indie roguelikes like FTL: Faster Than Light later refined Blazar’s approach to randomness. Elements Interactive never revisited the IP, pivoting to mobile puzzlers like Snowed In 5.

Conclusion

Blazar is neither masterpiece nor failure—it’s a time capsule. Its procedurally generated levels and retro sensibilities anticipated indie trends, while its mobile-first design highlighted the era’s technical trade-offs. For shoot ’em up enthusiasts, it remains a curiosity worth revisiting; for historians, a testament to gaming’s awkward adolescence in the mobile space. Final Verdict: A flawed but ambitious bridge between arcade purity and modern procedural design.