- Release Year: 1990

- Platforms: Amiga, Atari ST, DOS, Windows

- Publisher: Mindscape International Ltd., Three-Sixty Pacific, Inc., Ziggurat Interactive, Inc.

- Developer: Artech Digital Entertainment, Ltd.

- Genre: Simulation, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Dogfighting, Flight Simulation, Hexagonal map, Turn-based combat

- Setting: Historical events, World War I

Description

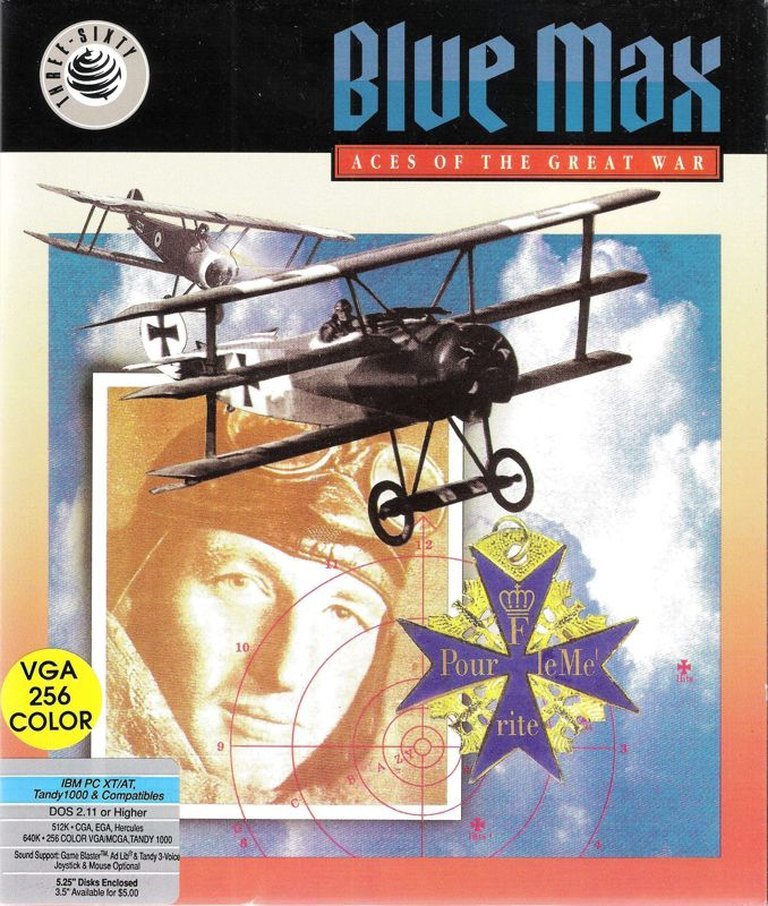

Blue Max: Aces of the Great War is a World War I fighter plane simulator where players engage in thrilling aerial combat, piloting iconic aircraft like the Fokker and Sopwith. The game offers both real-time dogfights and a unique turn-based hexagonal map mode, featuring split-screen multiplayer for cooperative or competitive play. With missions ranging from shooting down enemy planes to targeting specific objectives, it captures the essence of WWI aviation with a mix of action and strategy.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Blue Max: Aces of the Great War

PC

Blue Max: Aces of the Great War Free Download

Blue Max: Aces of the Great War Guides & Walkthroughs

Blue Max: Aces of the Great War: Review

1. Introduction

The skies over the Western Front in 1917 were a crucible of courage and innovation, where biplanes danced mortal duels above the mud and trenches. Into this historical tapestry, Blue Max: Aces of the Great War emerged in 1990, not as a dry simulation, but as a visceral, accessible tribute to the dawn of aerial combat. As the first major World War I flight simulator to blend arcade thrills with strategic depth, it carved a unique niche in an era dominated by technologically complex and niche flight sims. This review posits that Blue Max achieved its legacy by striking a delicate balance between action-packed dogfights and innovative tactical gameplay, though its ambition was often thwarted by technical constraints and design compromises. It remains a fascinating artifact of early 1990s gaming—a flawed yet influential pioneer that captured the romance of the “Knights of the Air” while planting seeds for future aviation epics.

2. Development History & Context

Blue Max emerged from Artech Digital Entertainment, a Canadian studio founded by veteran programmers Lise Mendoza and Philip Armstrong. Led by producer Jon Correll and design duo Rick Banks and Paul Butler, the team sought to demystify the burgeoning flight simulator genre. Their vision was clear: create an experience that honored the heroism of WWI aces without requiring players to master complex instrumentation. Released in 1990 for DOS, Atari ST, and Amiga (with a Windows re-release in 2021), the game operated within severe technological confines. The DOS version relied on floppy disks (3.5″/5.25″) and EGA/VGA graphics, demanding 512KB–1MB of RAM for optimal performance—barely sufficient for its 3D rendering engine.

The gaming landscape of 1990 was transitioning from arcade simplicity to immersive realism. While titles like F-19 Stealth Fighter catered to hardcore simulators, Blue Max aimed for the mass market. Its split-screen multiplayer (1-2 players) and hybrid real-time/turn-based mechanics were direct responses to the emerging trend of accessible multiplayer experiences. Yet, the team faced limitations: Amiga reviewers noted sluggish scrolling on lower-end models, while the DOS version struggled to maintain fluidity. Despite this, Artech’s commitment to innovation was evident in its unique “hex-map” feature, which attempted to merge simulation depth with strategic accessibility—a bold gamble against the era’s prevailing complexity.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Blue Max eschews a traditional narrative, focusing instead on the emergent story of the player’s pilot. There are no named characters or scripted dialogue; instead, the narrative emerges from gameplay loops: missions, kill tallies, and the constant threat of death. The player pilots iconic aircraft (Sopwith Camel, Fokker Dr.I, SPAD S.VII) against AI-controlled “Huns” or opponents in multiplayer, embodying the archetypal WWI ace. Themes of mortality and fragility permeate the experience. When a pilot is “killed,” their achievements are erased—a brutal mechanic that underscores the peril of aerial warfare. As one player reviewer noted, “Oil in your eyes, and if you’re not careful, bullets in your Sopwith.”

The game’s core theme is the mythologization of combat. Missions involve shooting down “double-deckers” or bombing targets, but the focus remains on individual heroism. The absence of deep storytelling shifts the weight to atmosphere: the roar of engines, the sudden silence of a stall, and the inevitable plunge during a death dive. Critically, Blue Max romanticizes war—sacrificing historical accuracy for the thrill of Snoopy-esque fantasy. Computer Gaming World lamented this, noting that “historical verisimilitude [was] slighted,” yet this was intentional. The developers prioritized the “feel” of being an ace over pedantry, crafting a tribute to the romanticized image of the Great War airman rather than a grim simulation.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Blue Max’s gameplay hinges on two interconnected systems: real-time dogfighting and optional turn-based strategy.

Core Flight Mechanics:

– Controls: Supports keyboard, mouse, and joystick. Movement is responsive but simplistic, prioritizing arcade action over realism. Banking, climbing, and diving are executed intuitively, but instruments require manual toggling—a design choice that streamlined gameplay but frustrated reviewers like Power Play, who criticized the “tangle of keys” during combat.

– Aircraft Physics: The flight model is accessible but deeply flawed. Critics noted that planes felt “overpowered,” performing impossible maneuvers like barrel rolls or Immelmann turns with ease. Computer Gaming World dismissed the model as “not a representation of reality,” sacrificing authenticity for fun.

– Combat: Dogfights are the heart of the experience. Machine gun fire is satisfyingly loud, but AI enemies are notoriously accurate, as The One observed: “Computer-controlled enemies fly too well and fire too accurately… hits are continual even during acrobatics.” Missions range from air-to-air combat to bombing runs, with objectives displayed before takeoff.

Innovative Hybrid System:

The standout feature is the ability to pause mid-dogfight and switch to a turn-based hex map. Here, movements and attacks are planned on a tactical grid, while the 3D view freezes in a window. This mechanic, praised by ASM as “unique,” attempted to bridge simulation and strategy. However, it often felt disjointed, breaking the immersion of real-time combat.

Progression & Persistence:

– Pilot System: Players create a pilot whose kills and achievements are tracked. Death resets progress—a harsh consequence that added tension but enabled exploitation (e.g., swapping save floppies to avoid loss).

– Multiplayer: Split-screen cooperative or competitive play (1-2 players) was a rarity in 1990, offering immediate social engagement.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound

Setting & Atmosphere:

Set during 1916–1918, Blue Max immerses players in the Western Front’s aerial theater. Missions feature historical backdrops like Somme and Verdun, though the world-building is minimal. There are no trench interactions or ground-based narratives; the focus is solely on the sky. This narrow scope heightens the claustrophobia of the cockpit but lacks the broader context of the war.

Visual Design:

– Graphics: For its time, the visuals were groundbreaking. The DOS version used VGA for richly detailed aircraft (thanks to Grant Campbell’s artwork), with “Digibilder” of double-deckers and pilots. Amiga reviewers lauded the “finest” graphics and sound for 1MB machines. However, lower-end Amiga models suffered from “diashow-like” rudder control when details were maxed out.

– Atmosphere: The cockpit view is minimalistic—no dials, only essential gauges on demand. This simplicity enhances focus on the enemy but sacrifices immersion. The death dive’s dramatic plunge, however, is a masterstroke of visual storytelling.

Sound Design:

Paul Butler’s sound design is a highlight. Engine noises dynamically shift with RPM, and machine-gun fire is punchy and authentic. Play Time noted the “best sound” was the death dive’s audio—a haunting crescendo of metal and wind. The Amiga version’s music (absent on 512KB models) added ambiance, but its absence on lower-specced systems dampened the atmosphere.

6. Reception & Legacy

Launch Reception (1990–1991):

Blue Max polarized critics upon release. The MobyScore of 6.7 reflects this divide, with critics ranging from The One’s 90% (DOS) to Amiga Power’s scathing 17% (Amiga).

– Praise: Most admired its accessibility and fun factor. ASM (DOS) called it a “clear hit,” while Play Time (Amiga) celebrated its “wind in your face” authenticity. The hybrid turn-based feature was frequently highlighted as innovative.

– Criticism: Technical flaws dominated negative reviews. Power Play (DOS) lambasted the “slow 3D graphics” and “lack of flight feeling,” while Amiga Joker noted the Amiga port was “sloppily implemented” for 512KB users. Historical accuracy was a common grievance—Computer Gaming World decried its “game over realism” approach.

Player Reviews:

Player feedback mirrored critics. One reviewer summed it up: “Not a lot of depth, but definitely a lot of fun.” They praised the graphics (“EGA stuff” was ahead of its time) but criticized the AI’s prowess and the death mechanic’s harshness.

Legacy:

Blue Max holds a unique place in aviation gaming history. Its hybrid real-time/turn-based system foreshadowed later genre experiments, though it wasn’t widely imitated. Its accessibility paved the way for more mainstream sims like Red Baron (1990). The Windows re-release (2021) attests to its enduring niche appeal. Critically, it remains a study in ambition versus execution—a title that dared to make WWI flight combat approachable but was ultimately hampered by the limitations of its era. As Retro Spirit noted, it was “ok for those who like the setting,” but its legacy lives on as a flawed but fascinating artifact.

7. Conclusion

Blue Max: Aces of the Great War is a game of contrasts: a revolutionary concept shackled by 1990 technology, a tribute to heroism that sacrificed realism for fun, and a flawed gem that nonetheless left an indelible mark. Its strengths—the visceral dogfights, the hybrid tactics, and the evocative sound design—shine as bold innovations. Yet, its weaknesses—unrealistic physics, inconsistent performance, and a punishing death mechanic—prevent it from being a timeless classic.

In the pantheon of flight sims, Blue Max occupies a unique space: it didn’t define the genre, but it expanded its boundaries. It proved that historical aviation could be thrilling without being impenetrating, and its influence echoes in later titles that balanced accessibility with depth. For modern players, it’s a curio—a glimpse into a time when developers dared to innovate on shoestring budgets. For historians, it’s a benchmark of early 1990s ambition. Ultimately, Blue Max is more than a game; it’s a time capsule of an era when the skies were wild, and dreams of flight were as simple as pulling a joystick. Verdict: A flawed but essential artifact of aviation gaming’s golden age.