- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Terminal Zero

- Developer: SC exosyphen studios SRL

- Genre: Action, Simulation

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Customization, Hacking, Hardware Upgrading, Mission-based, Mod support

- Setting: Cyberpunk, dark sci-fi

Description

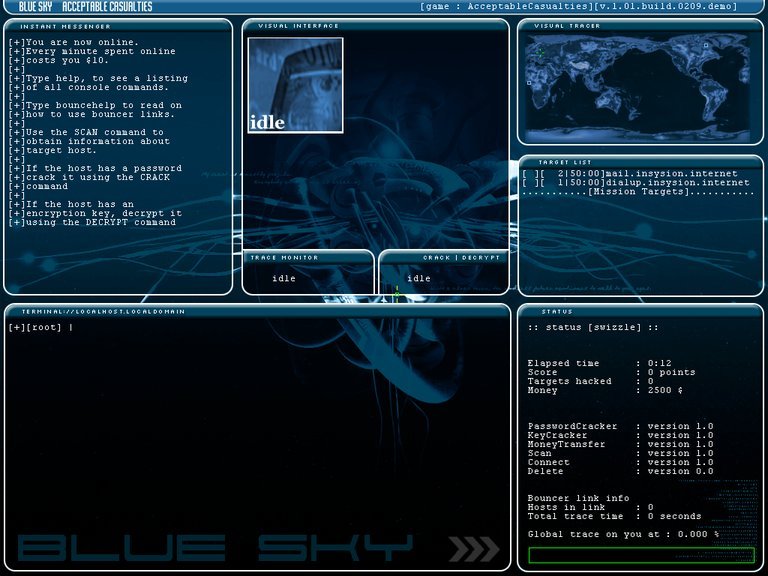

Blue Sky: Acceptable Casualties is a cyberpunk action-simulation game set in a semi-UNIX environment where players engage in hacking missions, such as stealing money, gathering intelligence, and uploading trojans, while evading detection to improve their scores. The game supports extensive customization through mods, custom skins, levels, and an SDK for adding new commands, with hardware upgrades being crucial for mission success in this dark sci-fi world.

Blue Sky: Acceptable Casualties: Review

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine

In the vast, digitized archives of gaming history, certain titles exist as spectral presences—mentioned in forums, cataloged in databases, but rarely experienced. Blue Sky: Acceptable Casualties (2002) is one such phantom. Developed by the obscure Romanian studio SC exosyphen studios SRL and published by Terminal Zero, this title represents a fascinating, deeply marginalized fork in the evolution of the hacking simulation genre. It arrives not as a mainstream curiosity like Uplink or later as a narrative-driven experience like Her Story, but as a raw, modular, and fiercely technical toolkit disguised as a game. Its legacy is not one of critical acclaim or commercial success, but of ambition: a project that prioritized player-driven creation and systemic simulation over polish, accessible storytelling, or marketability. This review will argue that Blue Sky is a significant case study in democratized game design and proto-modculture, a title whose true importance lies less in what it was and more in the open-ended, SDK-driven possibilities it explicitly offered to its players. It is a game that asked, “What if the player could rewrite the very rules of the hack?” and then provided the means to do so, placing it years ahead of the modding-centric ethos that would later define indie and even AAA development.

Development History & Context: The Romanian Netrunner

The Studio and the Vision

SC exosyphen studios SRL was, for all intents and purposes, a three-person operation. The core credits—Programmer Robert Muresan, Artist Rares Durigu, and Voice talent Edith Gusan—paint a picture of an intimate, almost familial development effort. This was not a corporate initiative but a personal project, likely born from the creators’ own fascination with cybersecurity, UNIX/Linux command-line environments, and the burgeoning “hacker” aesthetic of the late 1990s/early 2000s. The game’s title, Acceptable Casualties, is itself a stark, cynical piece of cyberpunk nomenclature, evoking the morally ambiguous world of freelance digital operatives where collateral damage in cyberspace is an acceptable business expense. This thematic choice suggests a desire to move beyond the simple “good vs. evil” of earlier hacking media and into a grittier, more nebulous space.

Technological Constraints and Aesthetic Choices

The year 2002 placed the game in a specific technological window. Windows XP was dominant, broadband was spreading but not ubiquitous, and 3D acceleration was standard. Yet, Blue Sky deliberately eschewed 3D for a “semi-UNIX environment.” This was both a constraint and a design philosophy. On one hand, it allowed a tiny team to create a complex simulation without the immense resource expenditure of 3D modeling and animation. On the other, it was an authentic, purist’s choice. The game’s UI is the game world—a series of terminal windows, command prompts, and textual feedback. This decision aligned it with the “text adventure” lineage but updated it with a real-time, risk-assessment layer. The “art” was not in polygon counts but in the design of clear, functional, and atmospheric HUD elements and the promised ability for players to create completely new “skins” and graphics.

The Gaming Landscape

2002 was the year of No One Lives Forever 2, Return to Castle Wolfenstein, and Warcraft III. The “hacker game” niche was being explored, most notably by Introversion Software’s Uplink (2001), which had established the benchmark for a stylish, accessible, and game-like hacking simulation. Uplink used a graphical node-map interface. Blue Sky’s choice of a literal command-line interface was a direct, more hardcore counter-proposal. It catered to a niche audience with some terminal familiarity, positioning itself as the simulation for simulation’s sake, not the gateway drug. Its release shortly after Uplink suggests it was either unaware of or intentionally divergent from that hit, aiming for a different, more technically audacious slice of the same pie.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Stories Written in Trace Logs

Narrative in Blue Sky is not delivered through cutscenes or dialogue trees but is emergent and environmental, a feature shared with many simulation-focused titles. The source material consistently describes the core loop: “Steal money from the bank, get information on a person, upload trojans… complete your missions the way you want to.” The plot is a scaffolding, not the destination.

The Synecdochal “Contract”

The player is an “independent operator,” a ghost in the global network. The “shadowy syndicate” that gives missions is never named or characterized beyond being a source of contracts. This is a deliberate narrative technique: the syndicate represents the faceless, amoral capitalist/espionage machine of cyberpunk. The player is a “acceptable casualty” in their own right, a disposable tool. The missions escalate from “simple bank fraud” to “political sabotage” and “covert warfare,” mirroring a classic descent into moral ambiguity. The narrative progression is one of scale and consequence, not character development.

Lore in the Logs

The story is told through “encrypted emails” and “secure chat logs” with realistic headers and timestamps. This is where the game’s cyberpunk soul resides. The player must read between the lines, parsing metadata,Sender addresses, and the terse language of clients for clues about who is really pulling the strings. A mission to “gather personal data” on a corporate whistleblower might have an email chain revealing the client is a rival corporation. The ethical dimension—”whether to follow orders or pursue your own objectives”—is not presented as a morality meter but as a practical risk assessment: disobeying a client might mean losing future contracts, but following a morally repugnant order might trigger a hidden narrative branch where you are hunted by a new adversary.

The Unseen Conspiracy

The “larger conspiracy” hinted at is the ultimate modding potential. It’s a blank slate for narrative modders. The base game provides the tone—a world of “powerful entities manipulating global events from the shadows”—but the concrete details are absent, a void waiting for a community to fill. This is a radical, almost post-modern narrative design: the core story is a template for communal storytelling. The “loose narrative” that gives “context to each hacking assignment” is less a script and more a genre emulation engine, providing the rules (contracts, risks, factions) for players to generate their own tales of digital intrigue.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Terminal is Your Weapon

The gameplay is a masterclass in systemic, learnable complexity. It is not a series of puzzles with a single solution but a sandbox of exploit opportunities.

Core Loop: Recon, Infiltrate, Exfiltrate

1. Intake: Receive a mission brief (text file) detailing the target (e.g., “Bank of Nova Terra, Account #XX-XXXX”). Objectives are often open-ended: “Transfer $50,000 to account YY-YYYY” or “Retrieve file ‘Project_Pandora’.”

2. Reconnaissance: The player must probe the target system. Using a semi-UNIX command set, they might use nmap-like commands to scan for open ports, ftp to check for anonymous login, or social engineering via sendmail to phishing addresses harvested from the target’s public website. This phase is about information gathering as a resource.

3. Infiltrate & Exploit: This is the heart. The player must find a vulnerability. The system likely mentions this could involve “uploading trojans” or “exploiting backend vulnerabilities.” A robust simulation would include a database of known exploits (like a local exploit-db), a password cracking utility (john-like), or the ability to chain multiple small privileges into a full system compromise. The “semi-UNIX” environment means commands have real consequences: a failed sudo attempt might trigger an alert; a wget of a suspicious file could be caught by an antivirus heuristic.

4. Achieve Objective & Cover Tracks: Once inside, the player executes the mission goal. Then, the critical, often overlooked step: opsec (operational security). This means deleting log files (rm), altering timestamps, and planting false trails. Failure here leads to “being caught,” which the description states is a primary failure condition—likely resulting in a “game over” traceback to the player’s own IP (a mechanic later made famous by Uplink‘s “Agent” pursuit).

5. Progression & Hardware: “Don’t forget to keep your hardware updated.” This is a crucial, dual-purpose system. Financially, money earned from missions is spent on tangible upgrades: faster CPUs (reducing command execution time), more RAM (allowing more simultaneous processes/connections), advanced network cards (improving stealth or connection speed), and storage for tools. Mechanically, this creates a permanent progression loop that carries between missions. A poorly equipped hacker will fail against hardened targets, making hardware management a core tactical layer.

The SDK as a Gameplay Multiplier

The inclusion of an SDK for Visual C++ 6.0 is the game’s most revolutionary and defining feature. This wasn’t just for mods; it was for extending the simulation itself. A savvy player or modder could:

* Add new commands (ssh_bruteforce, sql_injection).

* Create new target system architectures with unique vulnerabilities.

* Script complex, multi-stage mission objectives.

* Design custom “security AI” behaviors.

This transforms the game from a product into a platform. The “custom missions, levels, and game mods” are not just new maps but potentially entirely new hacking genres—corporate espionage campaign, NSA penetration testing trainer, or a multiplayer “hack vs. defense” mode.

Innovation and Flaws

The innovation lies in its uncompromising systemic depth and open toolset. Its flaws are equally profound and are evident in the Steam community discussions cited. The “extreme lag in GUI and typing” and “key mapping issue” point to a janky, unoptimized engine, likely a homebrew C++ creation by a small team without robust QA. The learning curve is described as “steep,” bordering on impenetrable for those without CLI affinity. The game demands a manual and a willingness to fail. This is not a bug but a feature for its intended audience, yet it guaranteed obscurity.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of the Terminal

The world of Blue Sky is not rendered in polygonal cityscapes but in the psychogeography of networks.

Visual Direction & UI

The “semi-UNIX environment” is the world. The primary visual is a high-contrast terminal window. The default scheme is likely the classic green-on-black (or amber), evoking 1970s mainframes and 1990s hacker cinema (Hackers, Sneakers). The “custom skins” allow players to alter this dramatically—a “neon-infused hacker panel” might change the color scheme to cool blues and pinks, while a “retro amber” skin deepens the nostalgic feel. The HUD is the interface: system status bars (CPU load, network traffic), a list of active connections, and a scrolling “console output” window that serves as the narrative log, error report, and mission feedback all in one.

The Role of 2D Artwork

The “short but impactful” cutscenes and mission briefings with “stylized character portraits and stark backgrounds” are crucial atmospheric beats. In a game of pure text, these few images provide vital human context—a face to the client, a logo of the target corporation, a schematic of a server farm. They break the textual monotony and sell the “spy/espionage” theme. The artist, Rares Durigu, had to convey corporate sleekness, dystopian grunge, or technological menace in a few static images, a significant narrative responsibility.

Sound Design

The source material is silent on music, but logic dictates a minimalist, electronic, and tense soundscape. The sound of a modem handshake, the rapid clicking of keystrokes, the low hum of server fans, and the sharp beep of a system alert or a successful exploit would be the primary audio cues. The “voice” credit for Edith Gusan suggests some text-to-speech or limited voice clips for mission briefings or system notifications (“Connection established,” “Access granted,” “Trace detected”), adding a layer of immersion and urgency. The sound design would be functional, not atmospheric, reinforcing the simulation’s clinical, high-stakes feel.

Reception & Legacy: The Mod That Became a Game (Almost)

Commercial and Critical Reception: A digital Ghost Town

There are zero critic reviews aggregated on Metacritic. The MobyGames page shows it “Collected By” only 5 players. Steam community discussions from 2025 reveal a tiny, struggling community: threads about “extreme lag,” “fixing typing lag,” and “key mapping issues.” This is the litmus test: a game with a functional community, even a small one, has active modders and troubleshooters. The presence of these threads indicates a handful of persistent enthusiasts, but also the crashing limitations of the original code on modern systems. It was not a commercial success. It was not reviewed by IGN, GameSpot, or PC Gamer. It existed on the fringes, sold perhaps via direct download or obscure shareware portals.

Legacy: The SDK as a Seed

Blue Sky‘s legacy is almost entirely conceptual and mechanical. It predates the widespread “games as platforms” philosophy by nearly a decade. While Uplink was the polished, influential face of the genre, Blue Sky was its raw, open-source heart. Its direct legacy is the “Hacker Games Launcher series” and its sequel, Digital Hazard (2003), suggesting the tiny team continued to iterate on their engine.

Its true influence is diffuse and speculative:

1. Modding Precedent: It stands as an early, explicit example of a commercial game shipping with a full C++ SDK, inviting players to be co-developers. This philosophy would later become central to the success of games like Arma 2/3, Minecraft (mod APIs), and the entire Skyrim modding ecosystem.

2. Purist Simulation Niche: It carved out a space for the “terminal as UI” approach that games like Hacker Evolution (2008) and Dystopia (a Source mod) would explore from different angles. It validated the idea that complexity could be a feature, not a bug, for a dedicated subset.

3. Archival Curiosity: For historians of the “cybersecurity game” subgenre, it is a primary source document. It represents a specific Romanian/Western-European indie perspective from the post-communist tech boom era—a group building a hyper-capitalist, cyberpunk simulator with the tools at hand, unburdened by the expectations of a Western publisher.

Conclusion: A Flawed Artifact of Pure Potential

Blue Sky: Acceptable Casualties is not a great game by any conventional standard. It is likely frustrating, buggy, and visually sparse. Its narrative is skeletal, its accessibility non-existent for the uninitiated, and its commercial footprint minuscule. However, to dismiss it as merely a failed Uplink clone is to miss its profound, if unrealized, ambition.

It is a game about hacking that was itself hacked together, a perfect metaphor for its own content. Its core innovation was treating the game engine not as a closed system but as a vulnerable platform waiting for user exploitation. The SDk was not an add-on; it was the point. In this, Blue Sky was decades ahead of its time, preaching the gospel of user-generated content and systemic play in an era of linear, scripted single-player experiences.

Its place in history is not on a pedestal but in a display case labeled “Important Experiments.” It is a testament to the idea that games could be tools, canvases, and shared systems. For every player who struggled through its laggy terminal, there was a potential modder who saw its SDK and imagined a new world. In that sense, Blue Sky: Acceptable Casualties was not a singular product to be consumed, but a seed planted in the codebase of gaming culture, one that would take years to truly sprout in the mainstream. It is a flawed, obscure, but fundamentally important artifact—the ghost in the machine that whispered the future.