Description

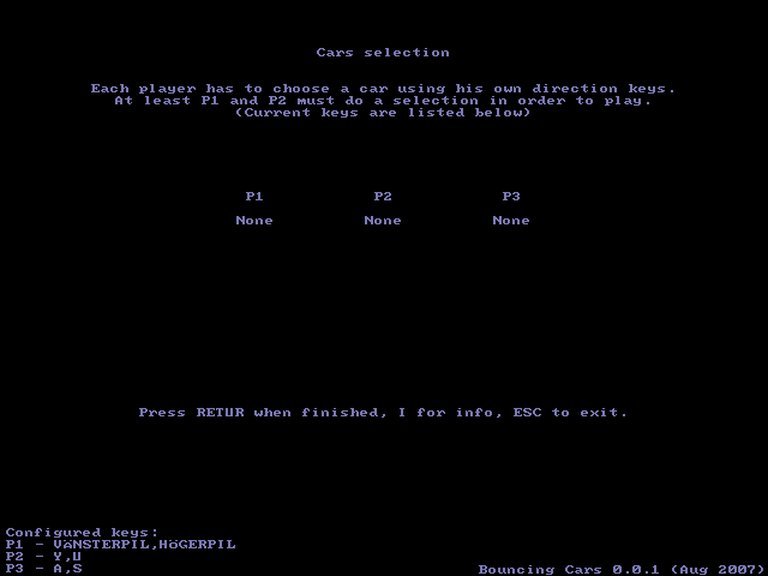

In Bouncing Cars, two to three players compete to collect 10 stars on randomly generated maps. Before the race, each player selects a unique car design from seven available options. The top-down arcade gameplay challenges players to navigate various obstacles including oil spills, ice patches, bushes, and roadblocks while racing to collect stars first.

Bouncing Cars: Review

Introduction

In the vast, often chaotic landscape of independent game development, certain titles emerge not as industry titans, but as curious footnotes—ephemeral digital artifacts preserved by niche communities and archival databases. Bouncing Cars, released in August 2007 for Windows, is precisely such a title. A freeware top-down racing game developed in relative obscurity, it exemplifies the era’s burgeoning digital distribution scene and the enduring appeal of stripped-down, multiplayer-focused experiences. This review will dissect Bouncing Cars through the lens of its design philosophy, historical context, and technical execution, arguing that while it remains a footnote in gaming history—a product of its time with limited innovation—it inadvertently captures a specific, forgotten charm rooted in local competition and procedural chaos.

Development History & Context

Bouncing Cars arrived during a transitional period for PC gaming. 2007 was the zenith of the seventh console generation, dominated by titles like The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion and Call of Duty 4. Meanwhile, the PC space saw a surge in casual gaming and digital distribution platforms like Steam, where freeware titles thrived as accessible alternatives. The game’s developer remains shrouded in anonymity within the MobyGames database, with only contributor Tomas Pettersson credited for its archival entry—a testament to the era’s grassroots development ethos. Technologically, Bouncing Cars embraced simplicity: its top-down perspective and sprite-based assets were relics of an earlier era, yet this constraint allowed it to run on modest hardware. Its procedural map generation—each session generated a unique layout—reflected a forward-thinking approach to replayability, a rare feature in 2007 for a freeware racing game. The vision was clear: prioritize local multiplayer accessibility over graphical fidelity or narrative depth, aligning with the legacy of “couch gaming” classics.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Bouncing Cars deliberately omits traditional narrative elements. There are no characters, plotlines, or dialogue—only the barest thematic framework of competition. The game’s “story” is distilled into a single objective: be the first to collect 10 stars. This absence of narrative is not a flaw but a design choice, funneling all engagement into raw gameplay tension. The themes are equally minimalist: rivalry, chaos, and resourcefulness. Players navigate abstract environments, turning mundane obstacles into strategic tools. For instance, oil spills become traps to slow opponents, while bushes force sudden detours. The lack of lore or backstory positions Bouncing Cars as a “pure” arcade experience, where the only character is the player themselves, defined by their reflexes and cunning. This thematic purity resonates with early arcade games, where narrative was irrelevant to the adrenaline of high-score competition.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The core loop of Bouncing Cars is a masterclass in minimalist design. Matches support 1–3 players competing locally via split-screen, a deliberate nod to pre-online multiplayer traditions. Each player selects one of seven distinct car designs—a critical feature that ensures visual differentiation and prevents duplicate vehicles, fostering individuality within the chaos. The goal is deceptively simple: race across a procedurally generated map to gather stars. The genius lies in the asymmetry of obstacles:

– Oil spills: Reduce speed, turning into tactical snares.

– Ice patches: Induce uncontrollable skids, adding unpredictability.

– Bushes: Act as immovable barriers, forcing route recalculations.

– Roadblocks: Complete obstructions that block paths entirely.

Combat is absent, replaced by environmental sabotage. Players must balance aggressive star collection with defensive positioning, using obstacles to hinder rivals without trapping themselves. The physics are rudimentary—cars bounce off walls and obstacles with cartoonish elasticity, a mechanic that amplifies the game’s chaotic energy. Progression is non-existent; there are no upgrades or unlocks, reinforcing the arcade ethos of immediate, replayable sessions. The UI is equally sparse, displaying only scores and timers, ensuring the focus remains on the action.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Bouncing Cars is a procedurally generated abstraction—a chaotic patchwork of roads, obstacles, and open spaces. Each match unfolds on a unique map, ensuring no two races feel identical. The art direction prioritizes clarity over flair: cars are rendered as simple, colorful sprites with distinct designs, while obstacles use bold, high-contrast shapes for instant recognition. The top-down perspective provides a godlike view, emphasizing strategic positioning over immersion. Sound design, however, is entirely absent in the archival records—a likely consequence of its freeware status, where audio assets were often omitted to save resources. This silence amplifies the game’s mechanical tension, making the screech of tires (implied) and the visual spectacle of collisions the only sensory feedback. The atmosphere is one of controlled anarchy, where the environment itself is the antagonist.

Reception & Legacy

At launch, Bouncing Cars received negligible attention. MobyGames records show zero critic reviews, and its single player review—a paltry 0.4 out of 5—speaks volumes about its obscurity and perceived quality. The low score likely stems from its primitive aesthetics and lack of depth, which paled against contemporaries like Burnout Paradise or Mario Kart DS. Commercially, as freeware, it generated no revenue but gained a cult following among small groups seeking quick local multiplayer thrills. Its legacy is twofold:

1. Niche Influence: It occupies a micro-niche within the “Bouncing” series of games (e.g., Bouncing Bill, Bouncing Heads), demonstrating a shared design language of physics-based chaos. However, it had no discernible impact on mainstream racing games.

2. Historical Artifact: As a preserved freeware title, it exemplifies the democratizing potential of digital distribution—a precursor to modern indie darlings like Fall Guys. Its procedural generation predates trends in roguelikes, though it never influenced their design.

Conclusion

Bouncing Cars is a time capsule—a flawed, forgotten relic of 2007’s freeware movement. Its lack of narrative, audio, and depth relegates it to the margins of gaming history, yet its frantic, local multiplayer focus offers a glimpse into a simpler era of competitive play. The procedural maps and obstacle-based strategy showcase admirable ambition, while its seven-car selection and physics-based chaos create moments of unintended brilliance. Ultimately, Bouncing Cars is not a great game, but it is a fascinating one—a testament to the enduring appeal of accessible, arcade-style competition. Its place in history is secure not as a trendsetter, but as a humble reminder that sometimes, the most memorable experiences arise from the most straightforward ideas. For historians and retro enthusiasts, it stands as a quirky footnote—a bouncing pixel in the vast sea of digital ephemera.