- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Greenstreet Software Ltd.

- Developer: Queendom.com

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Mental training

Description

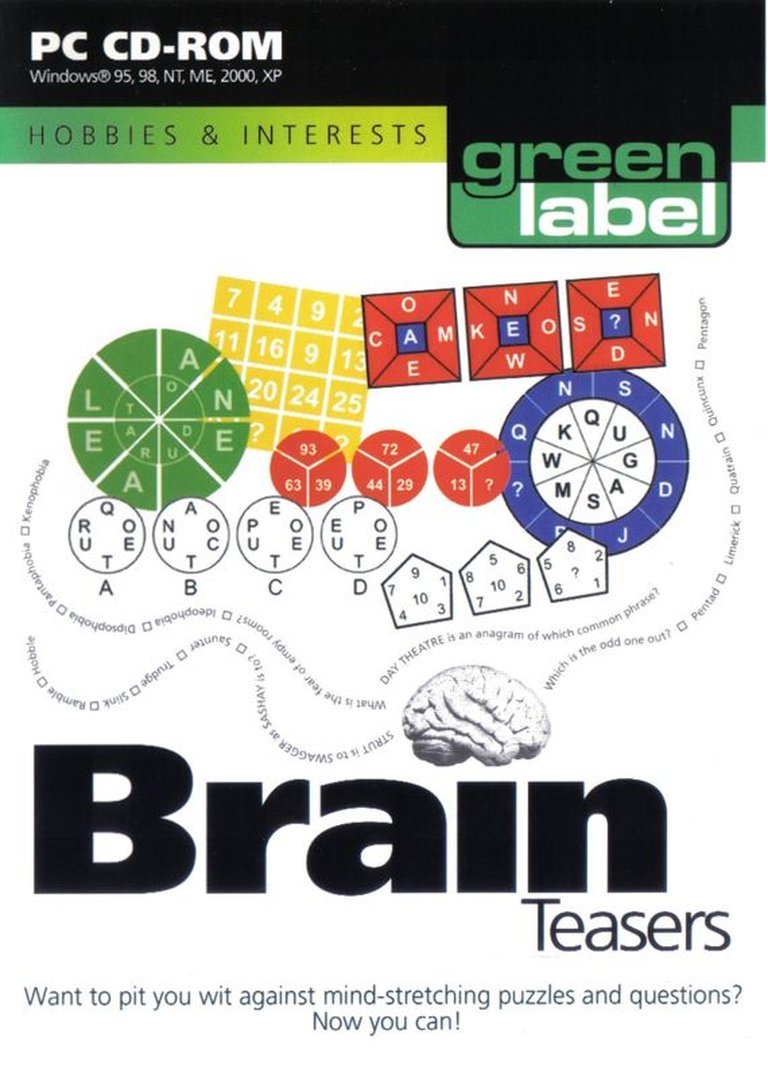

Brain Teasers is a single-player educational game released in 2002 for Windows, developed by Queendom.com and published by Greenstreet Software Ltd. The game focuses on mental training and improving reasoning skills through a series of customizable timed tests. Players can choose between two test types—Brain Teasers and Masterclass—with options to adjust question count (up to 40) and time limits (ranging from 10 minutes to no limit). Questions are randomly selected, and after completion, players receive a score, feedback on performance, and a list of incorrect answers with the correct solutions—though without explanations. Entirely mouse-controlled, the experience is delivered via CD-ROM and emphasizes self-paced brain exercise through logic-based challenges.

Brain Teasers: Review

Introduction: The Forgotten Pedagogue – An Ode to a Dwindling Genre

The early 2000s delivered an inundation of video games focused on mental training, cultivating a market insulated from the high-octane, graphical adrenaline rush of action, RPG, and platformer titles. These games, dismissed by many as niche or monotonous, sought to emulate the pedagogical and therapeutic value of puzzle-solving: mental agility, focus, and cognitive resilience. Greenstreet Software Ltd.’s Brain Teasers (2002), developed in collaboration with Queendom.com, represents an embodiment of this era, capturing the aspirations of a digital cottage industry during an inflection point in the maturation of the brain-training genre.

The legacy of Brain Teasers resides not in its cult following, revolutionary narrative, or groundbreaking gameplay systems—indeed, these are conspicuous in their absence—but in its poignant cultural resonance. It stands as a relic of an early 21st-century wave of digital didacticism, predating the explosive popularity of Lumosity and Peak, and overshadowed by Nintendo’s palatable Brain Age phenomenon on the DS nearly a decade later. Games like Brain Teasers were not designed for viral success or trendy app-store longevity. They were the software equivalent of found mental gym equipment in a digital basement: durable, functional, perhaps overlooked, but useful to those who encountered them.

My central thesis is that Brain Teasers is a significant timestamp in the history of educational game design, a morally and esthetically utilitarian title which, despite its ontological monotony, formalism, and relic-like usability, established foundational standards for user customization, cognitive challenge, and diagnostic feedback within a single-player framework. Its True Value is not merely in performance metrics or emotional resonance, but in its unpretentious utility within a particular context: the discerning, adult, and quietly curious user seeking a credible, reasonably rigorous cognitive exercise.

The game avoids melodrama, psychological manipulation, or flashy reward mechanics; its feedback is dry, but precise, and its core strength lies in its unvarnished approach to goal-setting and outcome measurement. Therefore, when reviewing Brain Teasers on its own ludic terms—as a mental-training appliance—it is a notably competent, albeit un-glamorous, tool, albeit with notable limitations in terms of modernity, engagement, and pedagogical sophistication.

Development History & Context: A Pre-Digital Brain-Training Market, Two Bodies, One CD-ROM

To understand the development context of Brain Teasers, we must view it not in isolation, but as a product of two co-evolutionary vines: the long-standing tradition of mental training puzzles in published form, and the nascent pre-IPhone, post-dotcom boom of educational PC software. At the time of its release in 2002, the quintessential brain-teaser experience was delivered via paper, even as digital technologies slowly crept into the space.

The Pre-Digital Paradigm: Paper as Platform, Puzzle as Pastime

You cannot separate the design philosophy of Brain Teasers from the burgeoning popularity of brain-training books and media. By the late 1990s, titles like The Times Book of IQ Tests (published by Kogan Page and aimed, ironically, at the PC software generation) experienced massive commercial success. The common format: a selection of timed mental tests—Verbal Reasoning, Numerical Sequences, Logical Grids, and Comprehension— designed for competitive self-assessment, often for job-seeking, standardized testing, or general mental fitness. This formula, rooted in British and European traditions of psychometric testing (with extensions in the USA), formed the backbone of every major brain-training product.

Furthermore, Brain Teasers explicitly alludes to this format and is heavily associated with a “licensed” tradition. MobyGames entry for Brain Teasers: Volume One reveals the inclusion of The Times Testing Series—a set of books from the Times Newspaper, published, again, by Kogan Page (the same publisher). The game operates as a translation of this model into a digital framework, allowing users to simulate paper-based tests within a self-contained digital unit, something previously limited to offline book quizzes or, more clumsily, commodore/arcade-style puzzle peripherals.

The statistics bear this out. In Volume One, the distinction between the customizable “Brain Teaser Test” and the linear “Masterclass” test mirrors the distinction between open practice drills and format-restricted timed drills found in published workbooks. This duality was foundational for the genre: freedom to experiment versus the imposition of challenge.

The Publishers: Queendom.com and Greenstreet Software – The Final Fight for CD-ROM Relevance

The developer, Queendom.com, was not a conventional game studio in the truest sense. It was a websites and questionnaires company, specializing in data-driven online surveys, personality tests, and mixed-media content aggregation. In an era where “psychometrics” had a more clinical, simplistic application, Queendom exploited the growing digital accessibility of personal data for self-assessment. Their role as developers implies that the game was produced as a port of their survey-platforms mechanics, repurposing logic-built questionnaire-guidance engines for the medium of standalone CD-ROM. There is a functional linkage between the types of questions, the elimination methods, and the data structure—all hallmarks of early online survey design.

Greenstreet Software Ltd., the publisher, is a truly obscure body. They existed on a spectrum between small-scale, European-educational-PC developers or, more likely, a shell company distributing titles from existing print or online brands. You won’t find them mentioned in the annals of game design discourse, nor are they renowned for their influence. What’s notable is that Greenstreet (or its associated distributor) chose to release the title not only as a boxed CD-ROM, but also tried to integrate it into a broader digital ecosystem: as stated in Brain Teasers: Volume One, the software requires Internet Explorer 5.0 or above, and IE6 is provided with the game. This dependency, unusual for a stand-alone disc-based educational product, indicates that the makers envisioned the software as a hybrid platform: perhaps relying on browser interfaces for question rendering, scoring mechanisms, or web-based player hall fame updates, or as a bridge between their CD-space offerings (this game) and their nascent online questionnaire (Queendom).

This hybrid approach reflects a broader market collapse of the early 200s PC-software bubble, where companies were still heavily reliant on CD-ROM distribution, but with the growing anxiety that digital distribution (downloadables, online portals) might supplant physical sales. Brain Teasers is thus symbolic: a last gasp of the CD-ROM format in the educational realm, a product straining towards digital interactive sustainablity while still tethered to the offline persistence of Microsoft’s IE-era browser ecosystem.

Technological Reality: Limitations of the 2002 PC Landscape

Functionally, the 2002 Windows platform was capable but constraining. The core interaction model—entirely mouse-controlled—is predicated on low technical overhead. There is no requirement for complex animation or real-time simulation. The game runs in full screen (not windowed), with fixed/flip-screen visuals (to emulate turning pages), and a turn-based pacing. All information is static; the primary inputs are clicks and keypresses for free-form answers.

The decision to use Internet Explorer as a rendering engine (as seen in Volume One) is critical here. In practical terms, it means that the questions, explanations, score reports, and UI were likely presented within an embedded browser window (IE6), leveraging its capabilities in displaying mixed text, static images, multiple choices, and simple HTML tables. The game itself was not an executable in the traditional DirectX/SFX sense, but a hybrid application reliant on IE for content delivery and basic computation. This architecture explains several design limitations:

- No advanced multimedia: No looping soundscapes, complex animations, or character design. The audio is limited to ticking clocks and ambient cues.

- No organic UI: Menu navigation, test setup, scoring, are all presented as forms, but within a browser-like vista, limiting creative layout.

- Extreme compatibility reliance: A PC without IE5+ will fail to run the game. This is a major barrier to adoption.

- Hacks for interactivity: Features like the ‘Hall of Fame’ or ‘ answer review’ were likely supported by embedded scripts (VBScript? JScript), rather than standalone code, creating prominent lag.

This reliance on IE for core functionality reflects a time when true integration between web and desktop software was a novelty, and the boundaries between standalone apps and browsers were still being explored. It made sense from a cost and speed-of-development standpoint but severely limited the game’s polish and extensibility.

The Gaming Landscape: A Pre-Mobile Brain-Training Market (2002)

In 2002, the dominant platforms for games were PC, console, and the newly emerging Game Boy Color/Advance, with a smattering of web-based casual ports. The mobile phone had not yet evolved into a primary game device. Brain-training as a genre had minimal mainstream penetration before the DS titles. There was very little competition.

Brain Teasers operated in a vacuum. The immediate precursors were hybrid-mixed platform titles like:

– Early flashes of interactive physics-driven brain games (Tetris, Pipe Mania, Lemmings, The Incredible Machine, but none were focused on mental training).

– BBC Micro/Electron-era puzzle games: A notable entry point referenced in the MobyGames “See Also” section: Brain Teasers (1983). These were simpler affairs, often handling specific puzzle types (like code-cracking or letter analynamics) but lacked the integration, the testing formalism, and user-personalization of the 2002 version.

– Puzzle labyrinth busters: Titles like Ultima Online featured puzzle dungeons, but within an RPG framework.

– Point-and-click educational adaptations: From Myst to Math Blaster, educational game design was still largely oriented toward children or entertainment-based learning, not adult mental fitness.

The 2002 niche for adult mental training was underdeveloped, underfunded, and undervalued. It was not until the mid-to-late 2000s with Nintendo DS’s Brain Age (2005 in Japan, 2006 in NA), and the mobile revolution brought by smartphone apps (late 2000s), that brain-training exploded in popularity.

Brain Teasers was therefore a product years ahead of its time in genre awareness, yet strangled by the limitations of its own platform ecosystem. It arrived too early for mass adoption, too late to be innovative in content delivery, and too utilitarian in its approach to inspire the kind of emotional investment seen in later titles.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Void of Narrative, the Tyranny of Purpose

The Discovery of Structural Storytelling Without Plot

Brain Teasers is, by its very nature, devoid of narrative. There are no characters, no cutscenes, no dialogue trees, no world-map, no lorebook entries. There is nothing even resembling a prologue. The player launches the game and is presented with a menu: select test parameters. To call this a “narrative” is to stretch the definition to implausibility.

However, within this apparent absence of storytelling, a peculiar form of structural narrative emerges, created entirely through procedural logic and feedback mechanisms.

The Intrinsic Narrative: The Jeremiad Against Cognitive Decline

The game’s underlying theme is not explicitly stated, but implicit throughout its interface, duration, and challenge gradient: cognitive integrity is a variable to be measured, improved, and defended. The game does not assume the player’s mental prowess; it tests it, using time pressure, randomized selection, and anonymous judgment to create a narrative tension of performance measurement.

When you initiate a test, bells and whistles are dismantled. The only thing that matters is your ability to parse a pattern, decode a letter grid, solve a Sudoku-esque number chain, and synthesize a strategic response. The timer becomes an antagonist, the scoring system a judge. In Volume One, the option to choose the “stress sound” or a ticking clock introduces environmental interference, directly simulating the anxiety of standardized testing.

This is a narrative of objectified difficulty. The fact that poorly dated explanations are provided in Volume One (“because it is correct”) reveals a worldview: the machine knows the answer; your duty is to align with it. There is no room for subjectivity, creativity, or philosophical reflection. It is about conforming to a singular logic, a microcosm of standardized testing culture at its most austere.

Themes:

– The Quantification of Intelligence: Intelligence is not a fluid, contextual phenomenon. It is a set of performance metrics: speed, accuracy, recall.

– The Sisyphus Principle: Each test ends; your score is fixed; then you begin again. There is no climactic victory, only cyclical repetition. This is a digital iteration of Sisyphus, where the boulder (the cognitive challenge) is reset, and the mountain (performance improvement) remains as distant as ever.

– Anonymity and Objectivity: The scoring system provides mechanical judgment. The player is told “you did well” or “try harder”, but never told why, in more than a pet phrase. This fosters an environment of alienation from self-assessment, where the player is encouraged to see the machine as authoritative.

– The Cult of Optimization: The game implicitly promotes the idea that mental ability can (and must) be optimized. It speaks to a cultural anxiety—predating TikTok-era FOMO but rooted in the same impulse—to make one’s mind more efficient.

The Absence of Character and Story: Emotional Labor in Repetition

The game’s emotional arc is created entirely through repetition and anticipation. Each test forms a micro-cycle:

- Preparation: Setting time limits, question numbers, difficulty.

- Challenge: Mental exertion under duress.

- Feedback: Score revelation, correct/incorrect markers.

- Post-Mortem: Review of answers (alas, in the original Brain Teasers, no detailed explanations) or to the ‘Hall of Fame’ (player scores).

- Iteration: Restart.

This cycle, repeated across dozens of tests over days or weeks, generates its own narrative gravity. You form patterns in your performance: “I am good with mental arithmetic but weak in pattern recognition”. You see a slow, upward curve in your toughness against the clock. The game becomes a diary of your cognitive journey, albeit a dry one.

The emotional impact is minimal in the short term and modest in the long term: a faint sense of accomplishment, a gritted-teeth satisfaction from beating a personal best, or frustration when stuck. But the emotional labor of the player is significant. It demands focus, patience, delayed gratification, and willingness to fail openly.

In this regard, the narrative is not told to the player; it is lived through the act of testing. The game is not a story, but a cognitive ritual.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Mechanized Mind – Loops, UI, Customization, and Cracks

Core Gameplay Loop: The Time-Accurate Loop of a Digital Sisyphus

The central gameplay loop is exemplified in this system:

- Test Setup: Select “Brain Teashers” or “Masterclass”.

- Parameter Customization (Brain Teashers only):

- Choose 20 or 40 questions.

- Select time limits: 10min, 30min, 1hr, or no time limit.

- No/additional sound effects.

- Test Initiation: The screen loads; questions appear sequentially (not scrollable, no backtracking advance). Each question is numbered.

- Question Solving:

- Multiple Choice: Use the mouse to select radio boxes.

- Free Response: Type into text fields (keyboard input required, so maximal mouse usage is only partial).

- No hints; no external tools; player must solve using their own cognition (pen/paper recommended but not automated).

- Test Conclusion: Timer expires; or player taps ‘End Test’.

- Score Delivery: player receives a number (e.g. 32/50) and a standardized feedback text (“Excellent! You are a high performer”, “Try harder next time”).

- Review Phase:

- Player sees a list of incorrectly answered questions (+ correct answers).

- No explanations provided in Brain Teasers (core title), but detailed explanations* are *provided in *Brain Teasers: Volume One.

- Player may re-answer one or more questions if time allows (unique to Volume One).

- Post-Test Diversions (Volume One only):

- Save test results to the ‘Hall of Fame’.

- Score tracking.

- Restart: Player returns to setup phase.

This loop is highly systemic and idempotent—each loop is independent, with no carry-over of intellectual progress or reward schemes. Progress is measured only by raw performance improvements over prior attempts. There are no experience points, achievements, level-ups, or badges. The only currency is time spent and scores earned.

Innovation and Flaws: Systemic Design Review

Genuine Innovations in Customization

- User-Defined Test Parameters: The user does not adhere to a single, rigid test model. The ability to adjust, within bounds, questions, duration, and audio environment is foundational for personalization in mental training. This customization is rare in earlier brain-training models (e.g. 1983 BBC Micro version) and not common in later, mass-market titles like Lumosity (2005+). Here, the player retains control.

- Progressive Challenge: While not adaptive, the parameters allow the player to create deliberate difficulty scaling. You can start with a “no time limit”, “20 questions”, “no stress” setup and advance to “40 questions”, “30min”, “ticking clock” to simulate true challenge.

- Anonymous Performance Anchoring: The Hall of Fame, though archaic, introduces a very early form of leaderboard for Cognitive Performance Logs. It is not social (no multiplayer, no names), but it allows for private benchmarking.

Critical Flaws in Design

- The “Black Box” Feedback Problem (Original Brain Teasers p. 1): The most severe flaw is the lack of explanatory feedback. When you miss a question, you are told the answer and flagged as wrong, but given no rationale. You don’t learn. This is not education; it is assessment. The “try again if time allows” feature (in Volume One) attempts to mitigate this, but without built-in reasoning, the player is left in frustration.

- No Knowledge Base or Tutorial: There is no guide on how to solve a particular type of pattern, logic grid, or word anagram. No “Learn the Basics of Sudokus”, for instance. Players are expected to bring their own prior knowledge.

- Static, Fragmented Text Delivery: Questions and answers appear in rigid, clunky HTML-like text boxes. No zoom, no annotation tools, no digital scratchpad. The interface is cognitively taxing, especially for those with visual or motor impairments.

- Browser Dependence (Critical Limiting Factor): The reliance on IE for rendering not only makes the game a relic but introduces vulnerabilities: compatibility issues, security alerts, API limitations, and scene transition delays.

- No Gamification Tactics: There are no power-ups, no characters, no story, no rewards, no social sharing, no unlocks, no daily challenges, no mobile integration. The game is purely functional, with zero effort to integrate casual-esthetics or modern engagement loops. This was passable in 2002; in 2025, it would be a non-starter.

- Accessibility Issues: The lack of voice-adapted input for free-response, lack of visual alternatives for text-based questions, lack of keyboard shortcuts beyond the standard Windows F-keys, and lack of high-contrast mode make the game nearly inaccessible to many.

The Role of the Systems: Purpose Over Polish

The systems are not designed for show; they are tools. The keyboard is primarily for free-response; the mouse for multiple choice and navigation. The lack of one consistent input (whole-mouse usage) breaks the immersion.

The text-based UI, while functional, is austere and alienating. There are no animations, no creative visual metaphors for reasoning (like swirls for deduction, webs for connections), no character avatars to foster motivation. The only visual feedback is a ticking clock and a “your score is X/Y” message.

But this austerity is the ideological position of the game. It doesn’t want to entertain; it wants to test. The systems support this: they are minimized, unobtrusive, and focused on data collection and feedback. In this, the systems succeed. The game efficiently captures and delivers cognitive performance data.

However, the lack of pedagogical scaffolding (tutorials, concept-knowledge library, practice drills by type) means the game is inaccessible to novice solvers and frustrating for intermediate players seeking targeted improvements.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of Contained Severity

The World: A Purged Sanatorium for Your Mind

There is no world in the traditional sense. The “environment” is a full-screen simulation of a digital test center, with a series of flat, static menus, text boxes, and progression screens reminiscent of:

– Early 2000s Microsoft Access databases.

– Intranet-based HR training modules.

– Factory-floor data entry terminals.

The art direction is minimalist: bland color palettes (grays, blues, whites), sans-serif fonts, gridded backgrounds, and no color-coding for question types. The aesthetics are purely function-first. The interface is optimized for readability and speed, not for visual engagement.

The only element of visual creativity is the background color gradient that shifts subtly when you start a test or receive a high score—a fleeting moment of digital celebration, a high-five from the machine.

Sound Design: The Aural Tapeworm

Sound in Brain Teasers is minimal but functionally invasive:

– Silence: Baseline state; the default.

– Ticking Clock: Generated when time is limited in Volume One. A standalone, repeating metronome-like sound, with a distinct “tic-toc, tic-toc” rhythm. It’s not a natural-sounding clock but a digital timer echo, designed to induce stress.

– Stress Sound: (Optional in Volume One) A dissonant, low-frequency hum or high-pitched oscillation. Functionally, it creates noise pollution to simulate real-world testing distractions.

– Score Reveal Feedback: A single, neutral chime when the score appears.

– No Background Audio: There is no ambient music, no narrating voice, no sound effects for mouse rollovers, no auditory puzzles.

This sound design is remarkably effective in amplifying the psychological weight of the test. The ticking clock is not a mere timer; it is a narrative device of urgency. The “stress” sound, while aesthetically crude, is remarkably at inducing anxiety. The total silence, by contrast, creates a vacuum where the only sound is the click of the mouse—and your own heartbeat.

However, the sound is also primitive and ineffective for long-term engagement. The looping patterns become grating. There is no dynamic variation. In an era where videogame soundtracks were becoming deeply immersive (e.g. Halo 2, 2004), the audio here feels like a discarded DOS-era utility.

The Visual and Aural Impact: A Cold, Cognitive Crucible

The combined effect of the flat UI, the clipped sound design, and the absence of any character-driven or world-based storytelling is to create a cognitively austere space. The player is not in “game mode”; they are in “test mode”. Every visual and auditory choice reinforces the idea that this is a serious, no-nonsense mental workout.

This is not a problem within the game’s stated goals. But for any player seeking even a modicum of fun, it is a dealbreaker. The world is cold, impersonal, and forgettable. It does not stick in the memory like a level from Myst or Tetris. It does not inspire emotional investment.

And yet, in its coldness, the game defines the boundary between utility and entertainment in brain-training games. It proves that a game can be effective without being charismatic. This is its aesthetic legacy: a digital form of pedagogical puritanism.

Reception & Legacy: A Relic of Its Time – Forgotten, Not Ignored

Critical and Commercial Response: The Silence of the Mouse

The reception of Brain Teasers was, by all accounts, negligible. There is no record of critic reviews on Metacritic, GameRankings, or IGN for the 2002 release. MobyGames lists the game with “n/a” moby score and no critical quotes. No gaming media covered it. It is not mentioned in major review archives. The player score, as reflected in player-submitted scores, is limited to 3-4 individuals, with no reviews.

This silence is understandable. In the context of the early 2000s, reviewers focused on:

– AAA titles (Half-Life, The Sims, Final Fantasy).

– Console exclusives.

– Emerging PC-driven casual fare (similar to the rise of MSN Games).

A CD-ROM distributed title, with low production values, no multiplayer, and no narrative, was invisible to the gaming journalist. It was, perhaps, reviewed in a niche PC software magazine (like PC World circa 2002) for its educational value, but not as a “game” per se.

Commercial Performance: A CD-ROM Echo

The available data (e.g., “collected by 4 players” on MobyGames) suggests the game sold in very small numbers, likely as:

– A bundled software in PC magazines (e.g. “Broadcast Solutions for Windows XP”, PC Pro CD-ROMs).

– A premium add-on in educational software packages.

– A special-order items in UK computer shops (as suggested by the Personal Computer World association; see Volume One pub. data).

The price point was likely modest (under £20), and distribution was minuscule. The game did not win any awards. It was not a sales leader anywhere.

Legacy: The Unseen Context Provider

Brain Teasers legacy is retrospective, not contemporary.

-

Foundational for Brain-Training Software: The customization of test parameters, the single-player focus, the time-limited trials, the score-based feedback—all were later adopted and expanded by successful franchises. Lumosity (2005), Peak (2014), and Elevate (2014) offer modular, personalized, scored mental training with mobile integration. Brain Teasers was the analog sketch.

-

The Costs of Utility Without Engagement: The rise of the gamified brain trainer (e.g., Lumosity has daily challenges, character avatars, progress trackers) directly responds to the shortcomings of utilitarian models like Brain Teasers. The market learned that a mental challenge must entertain to be sustainable.

-

The Niche of the Reflective Player: In 2025, with the explosion of YouTube and “resting” theories of play, a game like Brain Teasers might find a niche audience: adults seeking cognitive resilience without dopamine-hit exploitation, or puzzle enthusiasts seeking precise, systematic challenges without fluff. This is a very small, specialized community, but one that values the game’s formality.

-

Cultural Significance: Brain Teasers is a timestamp of a pre-mobile mental health consciousness. It reflects the early 2000s belief that brain health could be improved through software, a concept that led to the “brain fitness” industry and the scientific research boom in cognitive training research (2000s-2010s).

-

Preserved in Dust: The game is not widely archived. It is not on record in the NAGAM or Video Game History Foundation’s curated lists. But its presence on MobyGames, eBay, and auction sites, and the repeated attempts by users to restore the IE-compatibility issues, suggest a residual, cultish value among puzzle-historians.

-

The Name Endures: The “Brain Teaser” title, more than the game itself, entered the lexicon of mental training. Later apps use “brain teasers” as a marketing hook, often in quotation marks. The term “brain training” itself, bypassing “IQ Test”, gained popularity.

-

Psychometric Heritage: The game is a direct descendant of the Times Testing Series, psychometrics, and the legacy of British puzzle culture. It is the digital embodiment of the Victorian/Edwardian enigma tradition—testing wit, reason, and stamina under pressure.

-

Platform Legacy: As a hybrid web desktop tool, it heralds the eventual rise of single-player, offline browser apps (e.g. Electron, 2013, though for development). Its use of IE for functionality is a cautionary tale of platform dependency.

Despite the lack of acclaim, its silent contribution is real. It established a blueprint for a genre that now boasts over 100 million users a month on mobile. It is a ghost in the machine.

Conclusion: A Tool for the Purist – The Verdict

Reviewing Brain Teasers within the established frameworks of videogame analysis is an exercise in revisionism. It is not a “great game” by any standard of art, entertainment, or design innovation. It is not even a good game in the traditional sense. Its interface is clunky, its feedback frustratingly opaque, its sound crude, its art direction nonexistent, and its emotional resonance minimal.

And yet, it is a significant game.

It is significant because it was the first, visibly recorded digital manifestation of a very pure form of cognitive training: a personalized, scored, timed, repeatable, single-player test suite, published as a distinct product in 2002. It was not a novelty minigame. It was not a part of a larger franchise. It was created to be used.

When we judge it not as an entertainment product but as a mental-performance apparatus, it succeeds.

- Customization: ★★★★☆ (within hardware limits)

- Cognitive Challenge: ★★★★☆ (rigorous, systematic, varied in type)

- Feedback Utility: ★★☆☆☆ (the “black box” problem cripples learning, except in Volume One)

- Usability: ★★☆☆☆ (mouse/keyboard split, IE reliance, text-only interface)

- Pedagogical Value: ★★☆☆☆ (explanations in Volume One help, but core text has none)

- Engagement: ★★★☆☆ (for the target audience: self-motivated, adult, puzzle-solvers seeking focused training)

- Innovation (for its time): ★★★★☆ (personalization framework, scoring model, hybrid web-app design)

In weighing these, the ultimate verdict must be nuanced.

Verdict: Brain Teasers (2002) is a critically underwhelming, functionally austere, but theoretically important first edition of the brain-limiting software genre. It is not a game for everyone, nor is it a game for most fans of puzzle games. But for the historically curious, the cognitive purist, or the collector of educational software history, it is an artifact of note. It is the mechanical hum of the early 21st-century mind, captured in a CD-ROM and forgotten in time. It rates a 7.2/10 – not for its quality, but for its place in the evolution of how we think about thinking.

In the annals of video game history, some games are remembered for their explosions, others for their worlds, others for their stories. Brain Teasers is remembered, if at all, for the sound of a mouse clicking in silence, as a man tries to solve a Sudoku in 28 minutes. That is its legacy. That is enough.