- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Shindo S.A.S.

- Developer: Little Worlds Studio SARL

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: Fixed / flip-screen

- Gameplay: Mental training

Description

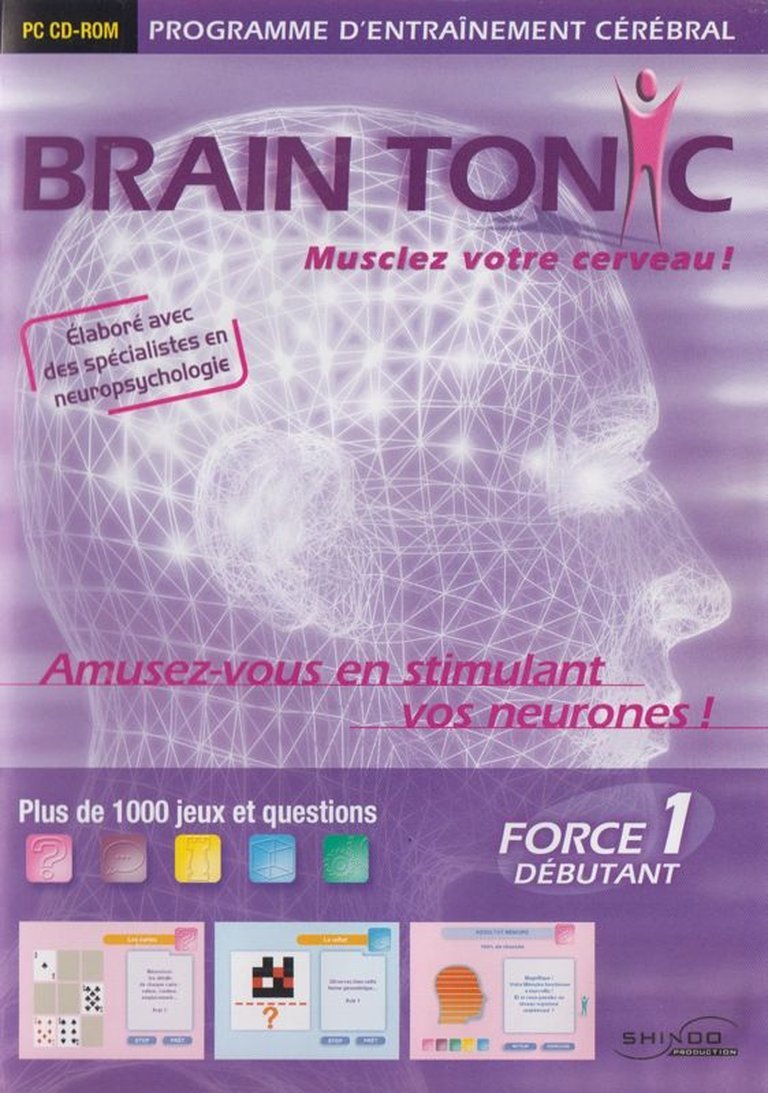

Brain Tonic: Force 1 is a puzzle-based brain-training game developed by Little Worlds Studio SARL and published by Shindo S.A.S. in 2007 for Windows and Mac. The game begins with a cognitive test to assess the player’s mental state, then offers tailored exercises designed to improve specific skills. It tracks progress through saved scores and recommends regular use three times a week. As the introductory title in the series, it sets the foundation for more advanced challenges in its sequels, Brain Tonic: Force 2 and Force 3.

Brain Tonic: Force 1: Review

Introduction

In the mid-2000s, as Brain Age and Dr. Kawashima’s Brain Training dominated Nintendo DS screens worldwide, a quieter contender emerged on Windows and Mac: Brain Tonic: Force 1. Developed by the obscure Little Worlds Studio and published by Shindo S.A.S., this brain-training oddity aimed to carve its niche in the cognitive fitness boom. Yet, like many early edutainment titles, it faded into relative obscurity. This review posits that Brain Tonic: Force 1 is a fascinating artifact of its era—earnest in its educational goals but hamstrung by rudimentary design and overshadowed by industry titans.

Development History & Context

The Studio & Vision

Little Worlds Studio SARL remains an enigma. Beyond Brain Tonic: Force 1 and its two sequels (Force 2, Force 3), no other titles are credited to the team. Publisher Shindo S.A.S., known primarily for distributing European abandonware titles (RetroLorean), positioned the game as part of a trilogy aimed at cognitive self-improvement—a clear bid to capitalize on the brain-training craze.

Technological Constraints

Released in 2007 for Windows and Mac via CD-ROM, Force 1 reflected the limitations of pre-digital-distribution PC gaming. Its fixed/flip-screen visuals and point-and-click interface mirrored simplistic Flash games of the era rather than contemporary AAA titles like BioShock or Portal. The focus on accessibility (keyboard/mouse support) prioritized function over flair, targeting casual users with low-spec hardware.

The Gaming Landscape

This was the peak of Nintendo’s brain-training hegemony. Brain Age: Train Your Brain in Minutes a Day! (2005) and Big Brain Academy (2005) had already sold millions, framing cognitive exercise as playful, habit-forming routines. On PC, however, similar titles struggled for visibility. Force 1 entered a market crowded with Solitaire-adjacent distractions and lacked the marketing muscle to compete.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Layers of “Lore”?

Brain Tonic: Force 1 eschews narrative. No characters, no plot—just a clinical presentation of mental challenges. If modern gamers obsess over the “lore” of Elden Ring or Silent Hill, Force 1 offers only procedural lore: progression metrics. Thematic unity lies solely in self-improvement, echoing the late-2000s cultural fixation on quantified productivity.

Underlying Philosophy

The game’s premise—test your brain, then train weaknesses—echoes Dr. Kawashima’s ethos. Yet it lacks that series’ charm; there’s no cartoon neuroscientist applauding successes. Instead, cold stat-tracking dominates. By framing cognition as a series of metrics to optimize, Force 1 unintentionally mirrors gamified self-help apps years before their ubiquity.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop & Progression

The game begins with a diagnostic test assessing memory, logic, and reflexes. Based on results, players engage in tailored exercises (e.g., pattern recognition, quick math). Scores save locally, encouraging thrice-weekly sessions—a structure mimicking fitness regimens.

Strengths & Flaws

– Innovative Structure: The adaptive test-to-training pipeline was novel for 2007, predating personalized learning apps like Duolingo.

– Cooperative Play: RetroLorean reviews note optional collaboration for complex puzzles—a rare feature for brain trainers, albeit underdeveloped.

– Repetitive Drills: Minigames lack narrative context or escalating stakes. Exercises feel sterile compared to Professor Layton’s puzzle-driven storytelling.

– UI Clunkiness: The minimalist interface feels functional but dated, with cumbersome menu navigation and no audiovisual feedback beyond scores.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Direction

Described by RetroLorean as “vibrant” and “colorful,” the art relies on abstract shapes and clean menus. While far from Super Mario Galaxy’s inventiveness, its simplicity avoids distracting players from cognitive tasks—a utilitarian choice over aesthetic ambition.

Atmosphere & Sound Design

The soundtrack is noted as “captivating” (MyAbandonware) but minimalistic, likely prioritizing focus. Sound effects are sparse; correct answers merit subtle chimes, while errors trigger soft buzzes. Unlike Brain Age’s playful feedback, Force 1’s tone leans clinical—more lab experiment than game.

Reception & Legacy

Commercial & Critical Performance

No critic reviews exist on MobyGames or elsewhere, suggesting minimal contemporary coverage. Sales were likely niche, given Shindo S.A.S.’s limited reach. Player reviews (RetroLorean) highlight nostalgia for its “unique puzzle mechanics” but concede its overshadowing by Nintendo’s offerings.

Lasting Influence

Force 1 left no seismic impact. Its sequels (Force 2, Force 3) faded further. Yet it foreshadowed trends:

– Edutainment Gamification: Its data-driven approach anticipated apps like Lumosity.

– Abandonware Subculture: Preserved on sites like MyAbandonware, it exemplifies early-2000s experimental PC titles now cherished as curios.

Conclusion

Brain Tonic: Force 1 is neither a masterpiece nor a disaster. It is a time capsule—a humble attempt to democratize cognitive training before smartphones turned such goals into global obsessions. While its gameplay lacks depth and its design feels antiseptic, it embodies the earnest, experimental spirit of 2000s edutainment. For historians, it’s a footnote; for abandonware enthusiasts, a relic worth revisiting. In the grand tapestry of gaming history, Force 1 is less a landmark than a stitch—small, forgotten, yet part of the fabric.

Final Verdict: A clinically functional artifact of the brain-training boom. Not essential, but illuminating for genre completists.