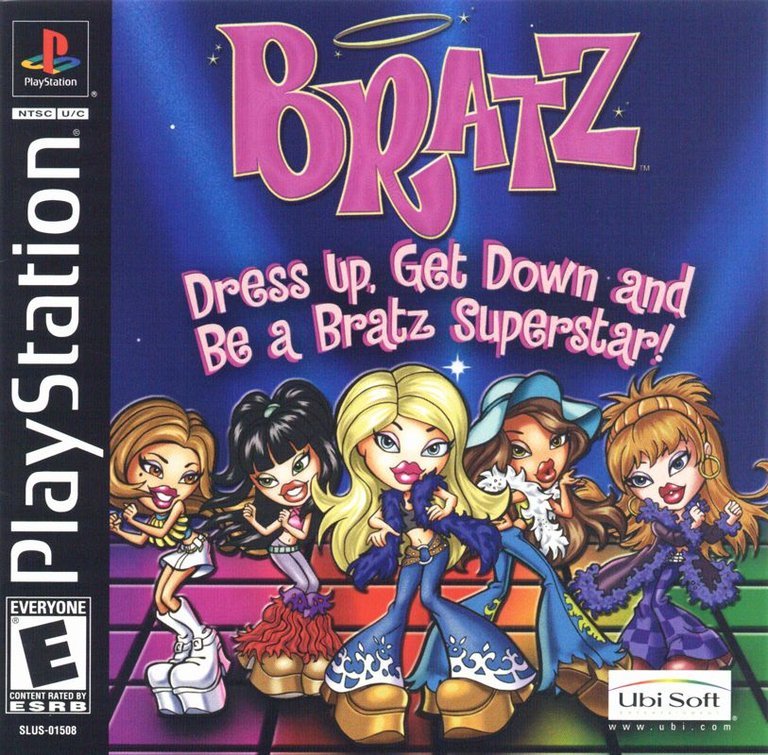

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Game Boy Advance, PlayStation, Windows

- Publisher: Ubi Soft Entertainment Software

- Developer: DC Studios, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Music, rhythm

Description

Bratz is a licensed dance rhythm game released in 2002, allowing players to embody one of five fashionable Bratz girls. Set within a competitive tournament structure, players practice and perform dance routines to progress. The game offers both single-player practice modes and multiplayer options, including competitive and cooperative ‘copycat’ modes for two players.

Gameplay Videos

Bratz Cheats & Codes

PlayStation 2

Enter codes at the small laptop near the computers in the Bratz Office.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| ANGELZ | Unlocks Passion 4 Fashion clothing line |

| SWEETZ | Unlocks Sweetz clothing line |

| SCHOOL | Unlocks High School clothing line |

| MOVIES | Unlocks Hollywood clothing line |

| PRETTY | Unlocks Feelin’ Pretty clothing line |

| PENNYZ | Gives you 500 Blingz |

| MOOLAH | Gives you 1,000 Blingz |

| DOLLAZ | Gives you 2,000 Blingz |

| TREATZ | Unlocks all treats |

Wii

Enter codes at the small laptop near the computers in the Bratz Office.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| ANGELZ | Unlocks Passion 4 Fashion clothing line |

| SWEETZ | Unlocks Sweetz clothing line |

| SCHOOL | Unlocks High School clothing line |

| MOVIES | Unlocks Hollywood clothing line |

| PRETTY | Unlocks Feelin’ Pretty clothing line |

| PENNYZ | Gives you 500 Blingz |

| MOOLAH | Gives you 1,000 Blingz |

| DOLLAZ | Gives you 2,000 Blingz |

Bratz: A Passion for Mediocrity in the Realm of Licensed Games

Introduction

In the glittering, brand-saturated landscape of early 2000s video games, Bratz arrived as a neon-colored contender. Leveraging MGA Entertainment’s massively popular fashion doll franchise, the game promised young players a chance to embody their favorite “girlz with a passion for fashion.” However, as this exhaustive analysis reveals, it ultimately embodied the era’s worst tendencies in licensed games: a rushed, undercooked rhythm experience suffocated by technical constraints and devoid of innovation. Beyond its veneer of trendy aesthetics, Bratz stands as a cautionary tale of how corporate synergy often undermines interactive potential—and why it remains relegated to bargain bins.

Development History & Context

The Studio & Vision

Developed by DC Studios, Inc. (known for niche adaptations like Jim Henson’s Bear in the Big Blue House and Cartoon Network Speedway) and published by Ubi Soft, Bratz reflected the gaming industry’s scramble to monetize youth-oriented properties. Released across PlayStation, Windows, and Game Boy Advance between 2002–2003, the game aimed to translate the dolls’ “attitude” and fashion-centric universe into interactive form. Executive Producer Mark Greenshields and Producer/Designer Stéphane Roy faced a daunting task: creating a multi-platform title targeting pre-teens amid fierce competition from established rhythm games like Dance Dance Revolution.

Technological Limitations

The game’s technical foundation was telling. Built using the Virtools 3D engine, it strained against hardware constraints—particularly on the Game Boy Advance. Animations were rudimentary, character models stiff, and environments sparse. This multi-platform approach diluted focus: the GBA version (released last in 2003) suffered from compressed audio and cramped visuals, while PlayStation and PC iterations offered little graphical advancement. Ubi Soft’s aggressive timeline—capitalizing on the Bratz brand’s peak popularity—prioritized speed over polish, resulting in minimal innovation.

The Gaming Landscape

Bratz launched into a market saturated with licensed titles, where film, TV, and toy franchises were hastily adapted with little regard for gameplay depth. Against contemporaries like The Sims (redefining life simulation) and Guitar Hero (revolutionizing rhythm genres), Bratz’s simplistic dance mechanics felt instantly dated. It targeted a demographic overlooked by core gamers but offered little beyond the brand’s iconography to retain interest.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot & Characters

The narrative was threadbare: players selected one of the five Bratz (Cloe, Yasmin, Sasha, Jade, or new addition Meygan) to compete in the “Bratz Tournament,” an 11-stage dance competition. No character arcs, rivalries, or story progression existed beyond unlocking outfits. The dolls’ personalities—central to the brand’s appeal—were reduced to idle animations and win/loss poses, stripping them of their trendy, aspirational identities.

Themes & Execution

Thematically, it echoed the franchise’s focus on self-expression, friendship, and style. However, these ideas manifest superficially through costume unlocks—hardly different from a digital sticker book. The promised “passion for fashion” translated to minor aesthetic customization rather than meaningful creativity. Dialogue was functionally nonexistent, replacing the dolls’ trademark wit with sterile menus and HUD prompts. Both narratively and thematically, Bratz failed to leverage its IP beyond surface-level branding, missing an opportunity to empower players through storytelling.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Rhythm Loop

Gameplay followed a rigid template:

1. Dance Battles: Using on-screen prompts (arrows or icons), players timed button presses to perform moves.

2. Freestyle Segments: Brief intervals allowed improvisation via simple combos.

3. Scoring: Accuracy dictated progression; higher scores unlocked costumes.

Two modes existed:

– Tournament: Solo play across 11 increasingly repetitive stages.

– Copycat: Two-player “Simon Says” mimicking, the sole multiplayer offering.

Critical Flaws

Critics universally panned its lack of depth. As Nintendo Power (score: 44%) noted, “Your character stands on one side of the screen while a graphic clues you in on what moves to make“—highlighting the static, non-immersive design. The GBA’s d-pad worsened input latency, exacerbating frustration. No difficulty scaling, unlockable songs, or meaningful progression existed. The “freestyle” segments, touted as innovative, felt disconnected and unrewarding.

UI & Progression

The interface was utilitarian but clunky. Characters moved mechanically, with rigid animations breaking immersion. Unlocking costumes (the sole “progression”) required enduring repetitive playthroughs—a shallow incentive that failed to leverage the fashion theme meaningfully.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design

Bratz’s aesthetic was its sole strength—yet still compromised. Character models loosely resembled the dolls’ exaggerated features but suffered from low-poly textures and robotic animation. Environments were barren stages with minimal interactivity, lacking the franchise’s glamorous backdrops (e.g., malls, clubs). The GBA iteration reduced visuals to garish sprites, stripping any sense of style.

Sound Design

Composed by Steve Szczepkowski, the soundtrack featured generic pop beats devoid of licensed tracks. Sound effects were tinny and repetitive, with no dynamic integration into gameplay. On GBA, compressed audio rendered songs grating. The absence of voice acting—especially the dolls’ distinct personalities—sapped the world of vibrancy.

Reception & Legacy

Critical & Commercial Response

Bratz was met with tepid reviews:

– Critics: Averaged 56% (MobyGames). 64 Power (68%) called it “langweilig” (boring) solo but noted fleeting two-player fun. Nintendo Power (44%) dismissed its simplicity.

– Players: Rated it 1.7/5 across platforms—savaging its repetitiveness and technical flaws.

Commercially, it leveraged brand recognition but quickly plummeted in value (now <$15 used).

Enduring Legacy

The game’s impact is twofold:

1. As a Cautionary Tale: It exemplifies early 2000s licensed-game pitfalls—rushed development, minimal innovation, and exploitative monetization of fanbases.

2. Franchise Footprint: Later Bratz games (e.g., Rock Angelz, 4 Real) iterated marginally but retained core flaws. Its failure indirectly highlighted the potential Diva Starz and similar titles wasted.

Within rhythm genres, it offered nothing to advance gameplay, paling against contemporaries like Space Channel 5 or even Britney’s Dance Beat. Today, it survives only as a curiosity among collectors of licensed oddities.

Conclusion

Bratz is less a video game than a branded obligation—a hollow shell where fashion and rhythm should have converged. Its rigid mechanics, woeful execution, and squandered IP potential render it historically significant not for achievement, but as a relic of an era when licensed games were too often cynical cash grabs. While later entries slightly refined its formula, this inaugural title remains a stark reminder that passion alone—whether for fashion or franchises—cannot redeem a lack of creative vision. For historians, it documents the nadir of early 2000s licensed games; for players, it is a relic best left on the shelf, its price tag a mercifully accurate reflection of its worth.