- Release Year: 2007

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ValuSoft, Inc.

- Developer: Brainfactor Entertainment Ltd

- Genre: Action, Compilation, Gambling, Puzzle, Sports

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Bowling, Cards, Darts, Mini-games, Sport, Target shooting, Tiles

- Setting: Casino

Description

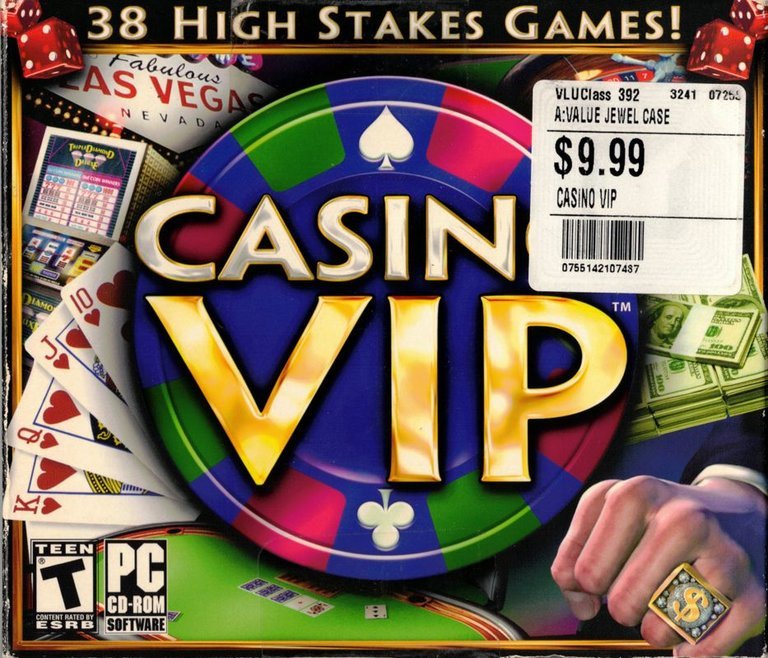

Casino VIP is a 2007 Windows compilation developed by Brainfactor Entertainment that bundles three programs: Texas Hold’em: High Stakes Poker, Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection, and the Casino VIP launcher. The launcher provides access to 32 mini-games across five categories—action, arcade, card, logical, and sports—featuring casino classics like blackjack and slots alongside skill-based games such as darts and puzzles, all designed for a Teen audience.

Casino VIP Free Download

Casino VIP Cracks & Fixes

Casino VIP: A Time Capsule of Mid-2000s Budget Compilations

Introduction: The Unassuming Jackpot of the Bargain Bin

In the sprawling ecosystem of video game history, certain titles serve not as pillars of innovation or narrative grandeur, but as precise archaeological markers of a specific time and market condition. Casino VIP, released for Windows in April 2007 by ValuSoft and developed by Brainfactor Entertainment Ltd., is one such title. It represents the final gasp of a once-thriving genre: the large-scale, budget-priced minigame compilation. This review argues that Casino VIP is not a “good” game in any traditional sense—it lacks a cohesive narrative, artistic vision, or technical polish—but it is an invaluable document. It encapsulates the late-2000s shift toward digital distribution and the decline of the physical CD-ROM compilation, while offering a raw, unvarnished look at the low-budget, high-quantity approach to game development that persisted in the shadow of the AAA industry. Its legacy is not one of influence, but of function: a practical, humble answer to the question, “What can you play on a PC for ten dollars?”

Development History & Context: The ValuSoft Ecosystem

The Studio and the Vision

Casino VIP was the product of Brainfactor Entertainment Ltd., a development studio that operated largely in the sphere of budget and compilation software for publishers like ValuSoft. The “vision” behind Casino VIP was inherently utilitarian. In the mid-2000s, the PC retail market, particularly at the $9.99 price point, was flooded with compilations—Hoyle Casino, Microsoft Entertainment Pack, WildTangent collections. Brainfactor’s role was to be an efficient producer of content. There is no evidence of an auteurial drive; instead, the game reflects a business model focused on volume. The package explicitly bundles two prior Brainfactor/ValuSoft releases: Las Vegas Casino Player’s Collection (2003) and Texas Hold’em: High Stakes Poker (2004), rebranding them as three distinct “programs” within a launcher. This repackaging strategy was common for extending the shelf life of existing codebases with minimal new investment.

Technological Constraints and the Gaming Landscape

Technologically, Casino VIP is a child of the Fixed/Flip-Screen era. Its visuals, as hinted at by the MobyGames categorization and available screenshots, are static or minimally animated 2D tables and interfaces, likely using DirectDraw or early Direct3D for simple sprite-based arcade games. This was a deliberate cost-saving measure. The year 2007 was a pivotal moment: Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 were in their prime, Steam was gaining traction, and casual digital titles like Bejeweled or Zuma were dominating the PC download space. Against this backdrop, a physical compilation of 38 simple games felt both nostalgic and obsolete. The target audience was clear: the non-gamer, the casual player seeking a quick distraction, or the absolute budget shopper. The ESRB “Teen” rating for “Simulated Gambling” was a standard, necessary checkbox that barely reflects the game’s content, which includes no realistic betting or nudity but revolves entirely around casino mechanics.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absence of Fiction

To analyze “narrative” in Casino VIP is to analyze a void. The game possesses zero narrative, character, dialogue, or thematic substance. It is a pure mechanics sandbox. The only “story” is the implied fantasy of being a “High Roller” and gaining entry to the “Millionaire’s Club,” marketing rhetoric printed on the box and repeated in official descriptions. This fantasy is not explored or represented in any meaningful way. There is no progression, no player avatar, no world to explore. The “VIP” title refers strictly to the collection’s supposed exclusivity, not any in-game status.

Thematically, the game is a hyper-stylized, gamified abstraction of risk and reward. Every minigame, from a bottle-spinner to a slot machine, reduces gambling or competition to a simple input/output loop. It presents a world of pure, consequence-free chance and skill-based micro-games. There is no exploration of addiction, risk management, or the culture of casinos—topics even more basic casino compilations sometimes touched upon in text descriptions or “fun facts.” Casino VIP is a pure Skinner box, offering immediate, low-stakes feedback. Its “theme” is not Las Vegas but the idea of Las Vegas as a hall of instant-gratification arcade games. This complete absence of narrative makes it a fascinating case study in non-interactive software; it is less a “game” and more a suite of interactive screensavers.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Launcher and Its 38 Children

The core of Casino VIP is its launcher interface, which divides its 38 included titles into five categorical menus: Action, Arcade, Card, Logical, and Sports. This taxonomy is both helpful and misleading, as it groups wildly disparate mechanics.

The Launcher & UI

The launcher is a simple, dated Windows 95/98-style menu with low-resolution thumbnails. It serves its purpose but offers no context, instructions beyond basic controls, or coherence. There is no meta-game, currency, or overarching progression system. You select a game, play it, return to the menu. The UI within each minigame is brutally functional, often relying on keyboard arrows and the spacebar or mouse clicks with no configurability.

Deconstructing the Minigame Menagerie

The true substance lies in the categorization and quality of the 38 games:

- Action (2 games): Simple reflex/collection tests. Bottle Turn is pure chance. Money Box is a basic avoidance game with a punishing element (collecting “0” coins).

- Arcade (11 games): The most diverse category, containing true arcade conversions or originals. Highlights include:

- 301/201 Purchase: Functional darts games against AI.

- Aim the Cards: A Space Invaders-esque shooter with a memory/resource twist.

- Bowling & Hurricane (air hockey): Simple but competent physics-based sports.

- Gnomes: A competent Snake variant with a fantasy skin.

- Memo5 & Super colors: Pattern-memory games that are clear clones/tributes to classic exercises like Concentration.

- Card (13 games): The core “casino” attraction, but with significant alterations and simplifications.

- Standards: BlackJack, Video Poker, Fruit Machine (slots), Mini craps.

- Notable Variants: Black Jack 2 introduces a fascinating, frustrating twist: you bet after seeing your cards, but the dealer can refuse the bet, adding a layer of psychological bluffing absent from standard Blackjack. Red takes all is a take on Slapjack with a cursed “red card” rule that instantly loses you the stack. TwentyOne hides all dealer cards, drastically changing strategy.

- Solitaire 2 is a notoriously harsh Klondike variant (single-card draw, no waste pile), highlighting the compilation’s tendency toward arbitrary difficulty inflation.

- Logical (5 games): Puzzle/solitaire-style games.

- amobawars is a simple Gomoku (Five-in-a-Row).

- Change cards and Coins are tile-swapping puzzles (SameGame/Lights Out variants).

- find the mines is a single-difficulty Minesweeper clone.

- Great 21 is a timed grid-based card summation puzzle, the most novel of the lot.

- Sports (1 game): Cash them all!, a simple crane game with a timer, representing the “prize counter” fantasy.

Innovative or Flawed Systems

Casino VIP has no innovative systems. Its “innovation,” if any, is in aggregation and hybridization. It bundles poker, blackjack, slots, craps, darts, bowling, memory games, puzzles, and snake-like games into one package, blurring the line between “casino simulation” and “minigame compilation.” The flaws are systemic:

1. Lack of Balance & Tuning: Many games are either trivially easy or arbitrarily hard (Colored numbers, Solitaire 2).

2. No Unification: There is no shared currency, achievement system, or “casino club” to tie the games together. They exist in isolated silos.

3. Repetition & Filler: The 32 “Casino VIP” program games feel padded. There are multiple slot machines (Fruit Machine, Pet Machine, Wild Machine), multiple blackjack variants, multiple darts games. This is quantity over curation.

4. Opaque Rules: Several games (Black Jack 2, Red takes all) provide no tutorial text, leaving the player to deduce bizarre rules through trial, error, and frustration.

The core gameplay loop is choose-game > play-2-minutes > return-to-menu. It is the epitome of disposable, session-based play, perfectly suited for the “coffee break” demographic of the mid-2000s.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Sound of Silence (and MIDI)

Casino VIP inhabits a nonexistent world. There is no “casino” environment to explore, no大堂 (lobby), no rooms. Each game is its own self-contained, top-down or fixed-screen entity. The visual aesthetic is generic and dated, even for 2007.

* Visual Direction: Graphics are a mix of basic 2D sprites and simple pre-rendered or stock images for cards and dice. Color palettes are often dull or garish. The “VIP” fantasy is conveyed only through the launcher’s title and perhaps a gilded font on the game’s icon. There is no atmospheric lighting, no animation beyond card dealing or a spinning bottle, and no sense of place.

* Sound Design: The sound is the most telling artifact of its budget. It consists almost entirely of low-bit MIDI files for background music (often repetitive, generic “casino jazz” or “oriental” tracks for puzzle games) and crude, sampled sound effects (chip clicks, dice rolls, a slot machine “ching”). There is no voice acting, no dynamic audio, and often the option to turn sound off entirely. The audio experience is not immersive; it is a functional, and often quickly-muted, accompaniment to the visual noise.

Together, the art and sound create a zone of non-atmosphere. They do not evoke Las Vegas, excitement, or luxury. Instead, they evoke the feeling of a forgotten Windows folder, of a pre-installed OEM game, or of a demo discarded on a GeoCities page. The contribution to the overall experience is one of pure utilitarianism. You are not in a casino; you are operating abstracted gambling and game functions. This emptiness is, in its own way, historically significant—it shows the baseline level of production value for a mass-market compilation at the end of the physical PC game era.

Reception & Legacy: A Ghost in the Machine

Critical and Commercial Reception

Casino VIP exists in a state of near-total critical obscurity. As evidenced by the source material—MobyGames, IGN, GameSpy, VideoGameGeek, Backloggd—it has zero professional critic reviews and, remarkably, zero user reviews or ratings across these major aggregators. The “Moby Score” is listed as n/a. Its commercial performance is not documented, but its subsequent availability for $4-11 used on eBay and its presence on abandonware sites suggests it was not a major commercial success. It was a shelf-filler that did not achieve cult status or notoriety. Its lack of footprint in the gaming press and community forums marks it as a true non-event.

Evolution of Reputation and Influence

The game’s reputation has not evolved; it has stagnated into a historical footnote. It is not remembered fondly as a classic of the genre (unlike Hoyle Casino series or Microsoft Solitaire). Its influence on the industry is directly negligible. No subsequent game cites it as an inspiration. Its legacy is indirect and contextual:

1. As a Final Artifact: It is one of the last major, physically distributed Windows-only compilations of its kind before the market fully consolidated into digital storefronts like Steam, which favored individual titles or developer-specific bundles over generic publisher compilations.

2. As a Benchmark for “Shovelware”: It defines the late-2000s PC “shovelware” aesthetic: a large number of simplistic, often repeated game types, packaged with a glossy promise (“VIP Treatment!”) that the product inside cannot fulfill. It is a textbook example of value-through-volume.

3. As a Comparative Baseline: For historians studying the evolution of casino video games, Casino VIP serves as a contrast to more ambitious, rule-rich simulations. Its stripped-down, arcade-ified approach highlights what was lost when the genre moved toward pure simulation or mobile freemium models.

4. Preservation Status: Its availability on MyAbandonware (as a 700MB disc image) ensures it is preserved as software, but it has no active community, no mods, no speedrunning scene. It is a museum piece with no visitors.

Conclusion: verdict on a Virtual Vacuum

Final Verdict: Casino VIP is not a game to be enjoyed on its own merits. It is a functional relic, a commercial artifact from a bygone PC retail era. It fails utterly as a work of art, narrative, or engaging interactive design. Its minigames range from tolerably competent (basic darts, bowling) to frustratingly obtuse (Solitaire 2). Its presentation is soulless and dated.

However, as a historical document, it is profoundly revealing. It captures the moment when “casino game” meant “minigame compilation with card rules,” and when “value” was measured in megabytes and game count rather than depth or online features. It represents the last stand of the $9.99 CD-ROM compilation against the rising tide of downloadable casual games. Its complete lack of reception is itself a data point, marking the point where such products became so disposable they weren’t even reviewed.

In the canon of video game history, Casino VIP occupies a space analogous to a generic, mass-produced comic book from the 1950s—not read for its storytelling but studied for its printing techniques, distribution models, and cultural context of cheap entertainment. Its place is not on a pedestal, but in a display case labeled “The Budget Compilation, c. 2000-2010.” For the vast majority, it is best ignored. For the historian, it is an essential, silent witness to an industry in transition.