- Release Year: 1983

- Platforms: Arcade, Commodore 64, Windows, ZX Spectrum

- Publisher: Jetsoft, Ocean Software Ltd., Pixel Games UK

- Developer: Jetsoft

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Collecting, Maze, Shooting

- Setting: Castle, Dungeons, Medieval

- Average Score: 89/100

Description

Cavelon is a side-view arcade action game set in a medieval fantasy realm where players assume the role of a knight on a mission to rescue a princess held captive in a castle. To succeed, they must explore six treacherous dungeons, collect scattered door pieces to unlock exits, defeat the black wizard, and navigate time-sensitive mazes while avoiding or shooting aggressive knights and gathering bonus items for points.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Cavelon

PC

Cavelon Free Download

Cavelon Cracks & Fixes

Cavelon Guides & Walkthroughs

Cavelon Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (78/100): Surprisingly, has become a favourite of mine in the cute game category!

store.steampowered.com (100/100): Christian Urquart, author of the best selling Kong and Hunchback for the Spectrum has excelled himself here with this infuriating but compulsive medieval quest.

Cavelon Cheats & Codes

Commodore 64

Enter button sequences during gameplay or execute BASIC POKE commands before loading the game. Action Replay users can enter codes via the cartridge interface.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| D, F, R, T, I, K, L | Activates level selection; press 1-6 to jump to corresponding levels |

| POKE 23789,255 | Unlimited lives |

| POKE 15485,255 | Unlimited lives |

| POKE 15458,255 | Unlimited lives |

| POKE 33789,99 | Unlimited lives |

| POKE 25485,255 | Unlimited lives |

| POKE 24025,165 | Unlimited lives |

| POKE 27769,165 | Unlimited zaps |

| POKE 27796,165 | Unlimited zaps |

| SYS 11480 | Restart game |

Cavelon: A Knight’s Quest Through the Pixelated Labyrinth

Introduction: The Unassuming Castle Gate

In the vast, often-overlooked annals of early 1980s arcade and home computing, there exists a modest castle gate, half-hidden in the archives. Cavelon, released by the short-lived American studio Jetsoft in 1983 and famously ported to the ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64 by Ocean Software in 1984, is not a game that boasts blockbuster sales figures or revolutionary 3D graphics. Yet, to dismiss it as merely another Pac-Man variant would be to underestimate a deceptively simple, brutally challenging, and strangely charming design that captures a pivotal moment in gaming history. This review argues that Cavelon is a significant, if underappreciated, artifact—a bridge between the pure, abstract maze chase and the nascent action-adventure, and a testament to the creative ferment of the UK’s budget software boom. Its legacy is not in spawned franchises but in its DNA: a game about desperate navigation, tactical shooting, and resource scarcity under a ticking clock, mechanics that would echo in everything from Gauntlet to modern roguelikes.

Development History & Context: From Jetsoft’s Arcade Ambition to Ocean’s Home Computer Mastery

Cavelon was born in the twilight of the golden age of arcades and the dawn of the European home computer revolution. Its developer, Jetsoft, was a US-based outfit active circa 1983-1984, with Cavelon and Bongo as its only known releases. The studio operated in an era where arcade boards like the one for Cavelon—powered by a Zilog Z80 CPU and General Instrument AY sound chips—were complex, expensive, and required significant expertise to program. The game’s technical specs reveal a typical, yet robust, early-80s arcade rig: a vertical raster monitor (224×256 pixels), a 98-color palette, and support for two alternating players. The constraints were real: limited memory, primitive sprite handling, and the ever-present need to design for a quarter-per-play revenue model.

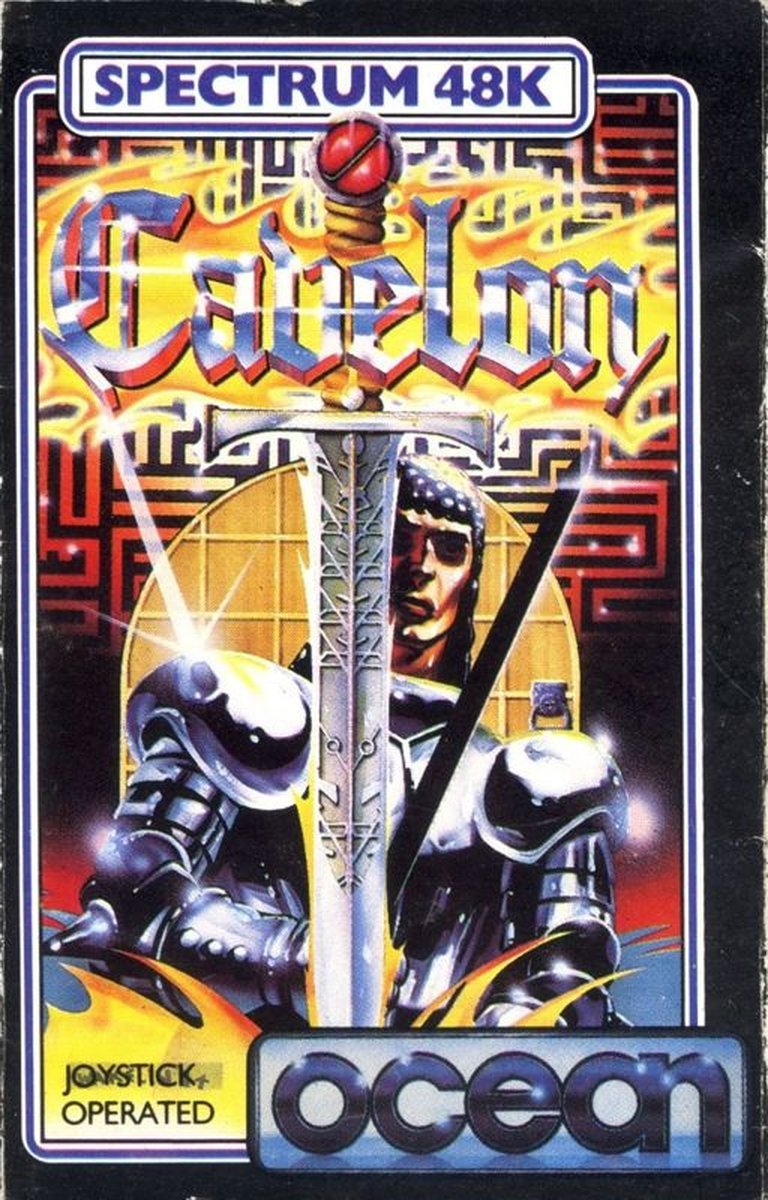

The critical chapter of Cavelon‘s story, however, is its British home computer transformation. Jetsoft’s arcade original was acquired and converted by Ocean Software, the powerhouse UK publisher known for both official licenses and, crucially, its “Original” budget range. The conversion team—credited on the Spectrum version as Paul Owens, Christian F. Urquhart, and F. David Thorpe, with cover art by the legendary Bob Wakelin—was the same core group behind hits like Hunchback and Kong. This was not a lazy cash-in. The team, working under producer D.C. Ward, had to reinterpret the arcade experience for the Spectrum’s unique attributes: its attribute clash color limitations, its slower processor, and its one-button joystick interface becoming a two-button keyboard or Interface 2/Kempston setup. They succeeded, creating versions praised for their “vivid colours” (on the C64) and clever use of the Spectrum’s 98-color palette to produce “cute knight and enemies,” as one modern player review notes. The 2022 Windows/Steam release by Pixel Games UK is an emulated preservation, adding modern conveniences like save states and controller remapping, finally allowing contemporary players to experience this historical artifact without the original hardware’s friction.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Arthurian Trite or Tortured Triumph?

On the surface, Cavelon‘s narrative is standard Arthurian kitsch: a knight (implicitly Arthur) must ascend a six-floor castle to rescue a princess (Guinevere) from a “black wizard.” The Computing History Museum’s description mildly subverts this, noting the “slightly strange parts” of collecting door pieces and the ultimate anticlimax that “Guinevere is not to be seen!” after defeating the wizard. This is not a story of courtly love but of ritualistic, Sisyphean labor.

The plot is delivered entirely through the title screen’s brief text and the in-game progression. There is no dialogue, no character development, no cutscenes. The knight is an avatar of pure function. The princess is a MacGuffin, a distant reward at the end of a computational gauntlet. The “black wizard” is less a character than a final boss frieze. This narrative minimalism is a feature, not a bug, of its era. The story exists to justify the mechanics: a castle (maze), a captive (goal), a villain (final obstacle). The theme is not chivalry but perseverance against systemic, aggressive opposition. The castle is a hostile workplace; the knights and archers are security guards who “shoot at you, even when their backs are turned,” a delightful touch of paranoid, omnipresent danger. The recurring cycle—enter a floor, collect 7-8 door pieces (the number varies slightly by source), fight through horde, proceed—cements a theme of compulsive repetition under duress, mirroring the player’s own attempts to master each lethal level. The “Excalibur” power-up provides a fleeting moment of godhood, a temporary reversal of the power dynamic, before the relentless reassertion of the castle’s guard force. It’s a stripped-down allegory for the grind of both arcade play and, one might poetically argue, the development process itself.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Calculus of Survival

Cavelon‘s genius and frustration lie in its tightly wound, brutally unforgiving core loop. It is a top-down, horizontally scrolling maze shooter, where each of the six floors is a single-screen-wide corridor that scrolls as the player moves left or right. The objective is to collect all scattered door pieces (7 or 8, per C64-Wiki and arcade specs) to unlock the exit. The genius is in the interlocking systems of risk and reward:

-

Combat & The “Infinite Shot” Paradox: The player fires arrows with one button. The second button activates Excalibur, a screen-clearing smart bomb that makes the player invulnerable for ~10 seconds. The innovative, infuriating twist is the shot cancellation system. As noted in the King of Grabs retrospective, “the bullet will only stay on screen until you press the first button again.” This means you can accidentally cancel your own arrow just before it hits a target. Enemies abide by the same rule. This transforms combat from reflexive shooting into a tactical timing puzzle. You must hold the fire button to keep the arrow alive, making you stationary and vulnerable. It’s a system that demands forethought and punishes mashing, creating a unique learning curve. Enemies vary: some knights die in one hit, others (archers, per C64-Wiki) require two, adding a layer of target prioritization.

-

Resource Management: The Excalibur Economy: Excalibur charges are limited per floor (often two, with a chance to find more floating swords). This is your panacea and your currency. Do you use it to clear a screen of 10 aggressive knights, or save it for a tight spot near door pieces? The “Zaps” (as the C64-Wiki calls them) are a finite, precious resource, making their management the game’s primary strategic layer beyond navigation.

-

The Tyranny of Time: A timer relentlessly ticks down. Its exact mechanics are obscure (the Arcade History site mentions it but not its pace), but its presence is felt as a constant psychological pressure. It forces movement, discourages over-caution, and turns exploration into a high-stakes gamble.

-

Progression & Scoring: After clearing all six floors, you face the wizard in a final chamber where you must collect one last set of door pieces while dodging his spells. Victory restarts the cycle at floor 1 with increased enemy aggression (a classic arcade loop). Bonus points are awarded for door pieces and other collectibles, but survival, not score-chasing, is the primary goal. The lack of continues after each round, a consistent criticism in player reviews (“I would have liked some continues after each round”), is a pure arcade holdover that makes the home computer ports brutally difficult by today’s standards.

-

Two-Player Hot Seat: A simple but effective addition, allowing rivals to take turns competing for a high score, fostering that classic arcade “one more go” competition.

The systems cohere into a experience that is “infuriating but compulsive,” as Big K magazine stated. It’s a game about controlled panic, where the maze is both your cage and your path to salvation.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Medieval Cutesy and Haunting Tunes

Cavelon‘s aesthetic is a fascinating clash of “cute” and “menacing,” a product of both technical limitation and deliberate design. The art direction uses the ZX Spectrum’s 98-color palette (a relative luxury for the machine) to create large, blocky, but expressive sprites. The knight is a simple, colorful figure. The enemies—knights with distinct colors and archers—are rendered with enough personality to be recognizable threats in a single glance. The maze walls are stark, creating clear pathways. The animation of the knight’s “quick feet movement” when moving is noted by players as “humorous,” adding a layer of personality rare in genre peers. The 2022 Steam re-release allows us to see these graphics cleanly, but the original Spectrum’s stark, attribute-clash-free look (impressive for an Ocean title) was a technical achievement that sold the “medieval” theme without raster tricks.

The sound design is where Cavelon transcends its visual simplicity. The Commodore 64 version, in particular, is celebrated for its music. Player reviews consistently praise the “appropriately jovial” and “Renaissance/harpsichord 2-part style” soundtrack. This is not generic chiptune; it’s an intentional evocation of courtly music, a sonic irony that plays beneath the violent gameplay. The sound effects—arrow thuds, the satisfying chime of collecting a door piece, the aggressive pew of enemy fire—are clear and functional. The juxtaposition of this cheerful, baroque music with the grim, frantic reality of being hunted creates a unique, slightly disorienting, but utterly memorable atmosphere. It makes the castle feel like a whimsical death trap, a theme park ride designed by a sadist with a good ear for melody.

Reception & Legacy: The Critical Split and the Quiet Influence

Cavelon‘s contemporary reception was mixed but generally positive, with a notable platform split. The ZX Spectrum version was a standout, winning 100% from Big K and an 86% from Crash magazine (which placed it 2nd in its “Best Maze Game” category for 1984). The Commodore 64 versions were slightly cooler, ranging from 80% (Commodore User) to 60% (Your Commodore). The criticisms were consistent: extreme difficulty, the lack of continues, and a perceived lack of depth beyond the core loop.

However, its legacy is more profound than its contemporary scores suggest. Firstly, it stands as a prime example of Ocean Software’s “Original” strategy. In the mid-80s, many UK publishers relied on cheap arcade licenses or clones. Ocean, with teams like the one behind Cavelon, invested in unique IPs that captured arcade sensibilities while feeling distinct. Cavelon, Hunchback, and Kong formed a quirky, creative portfolio that defined a generation of budget gaming.

Secondly, its mechanical DNA is faintly perceptible in later genres. The core loop of “navigate a dangerous space to collect scattered keys/items to progress, with a limited screen-clearing ability” is a direct ancestor to the dungeon crawler and, more specifically, to the co-op maze shooter genre epitomized by Gauntlet (1985). While Gauntlet added character classes and RPG elements, the frantic, item-collection-based progression through hostile mazes is Cavelon‘s blueprint. Even modern “backtracking” or “loop-based” roguelikes inherit this fundamental structure of repeating a perilous space with incremental gains.

Finally, its cult afterlife is secured by preservation efforts (Internet Archive, MobyGames, the 2022 Steam re-release) and a dedicated fanbase. Its rarity in the arcade collector’s market (the KLOV notes “very rare” with no known owned machines) adds to its mystique. It is a game that historian-curators dig up to illustrate the period’s design philosophy: challenge as the primary content, charm as a byproduct of technical necessity.

Conclusion: Verdict on the Castle Keep

Cavelon is not a lost masterpiece. It is a specialized, period-perfect tool, a fascinating case study in constrained design. Its narrative is skeletal, its graphics charmingly primitive, and its difficulty wilfully punishing. Yet, within these parameters, it achieves a remarkable coherence. The shot-cancellation mechanic is a stroke of brutal genius, transforming combat from a shooter into a game of chess with projectiles. The Excalibur economy creates tense, meaningful choices. The hauntingly jovial music etches an indelible audio signature.

Its place in history is secure as a pivotal bridge title: from the abstract mazes of Pac-Man to the item-hunting, combat-focused labyrinths of the late 80s. It represents the inventiveness of the UK’s home computer scene, taking an arcade template and infusing it with personality through conversion artistry. For the historian, it is a must-study example of early ’80s game adaptation. For the retro enthusiast, it remains a “surprisingly good maze arcade port” that demands patience and rewards mastery with that brief, glorious moment of invincibility. To stand at the top of Castle Cavelon, having outwitted the wizard, feels earned not through a grand story, but through the sheer, repeated act of surviving its elegant, merciless corridors. It is, in the end, a perfect, compact monument to the era when every game was a new puzzle, and every castle gate a formidable, pixelated challenge.