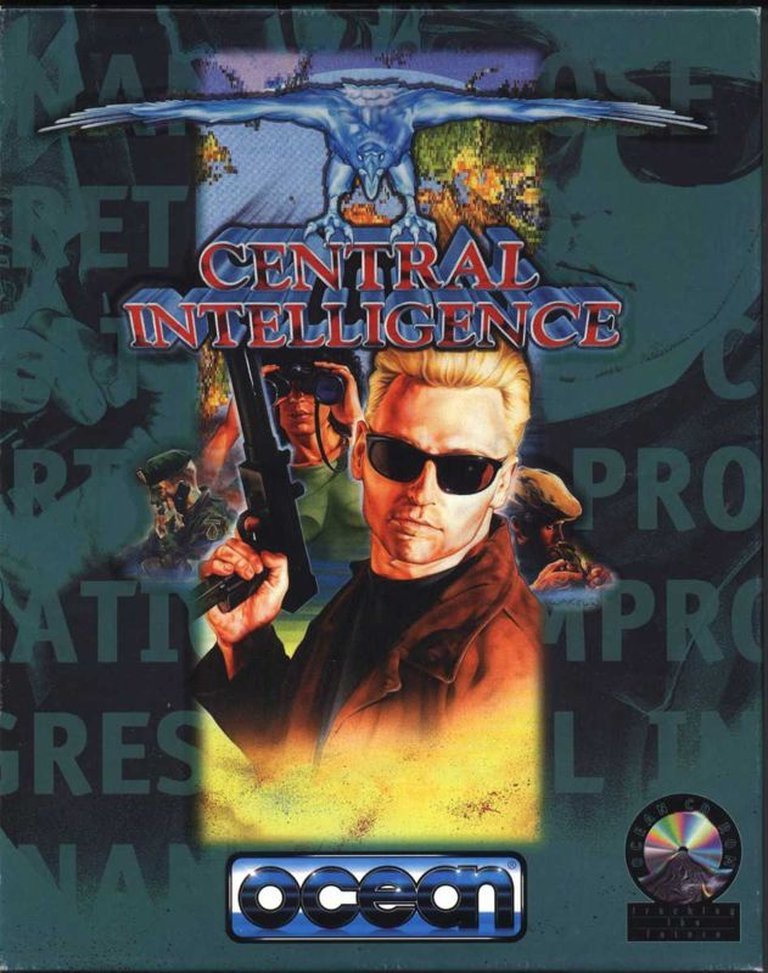

- Release Year: 1994

- Platforms: DOS, Windows

- Publisher: Ocean Software Ltd., Piko Interactive LLC

- Developer: Really Interesting Software Company (RISC)

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Agent management, espionage, Open World, Real-time, Strategy

- Setting: Dictatorship, Island

Description

Central Intelligence is a strategic espionage game set on the fictional island of Sao Madrigal, where players assume the role of a CIA chief tasked with overthrowing a Chinese-backed dictatorship threatening U.S. interests. Utilizing agents in political, propaganda, and military branches, players manipulate factions like students and guerrillas through covert operations such as propaganda, bribes, and assassinations to restore democracy, all while managing a real-time deadline and navigating a top-down satellite interface.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Central Intelligence

PC

Central Intelligence Free Download

Central Intelligence Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com : Great concept, flawed execution.

myabandonware.com : This truly is a hidden gem. Not the easiest game to learn, but it is fantastic none-the-less.

mobygames.com : Great concept, flawed execution.

Central Intelligence: A Scholastic Simulation of Subversion, Sabotage, and Systemic Suffering

In the crowded pantheon of 1990s strategy games, few titles stand out for their sheer, unadulterated ambition quite like Central Intelligence. Released in 1994 by the obscure Really Interesting Software Company (RISC) and published by the formidable Ocean Software, this DOS-exclusive title promised a deep, systemic simulation of covert regime change—a “geopolitical simulator” avant la lettre. Yet, for every brilliant stroke of emergent narrative and living world design, there was a corresponding flaw in user experience so profound it threatened to strangle the game’s colossal potential. This review will dissect Central Intelligence not merely as a forgotten strategy title, but as a fascinating, cautionary case study in the perils of prioritizing systemic complexity over player accessibility, and a testament to the audacious design dreams of the mid-90s.

Development History & Context: Ambition in the Age of CD-ROM

Central Intelligence emerged from the workshop of Really Interesting Software Company (RISC), a tiny UK development house with a pedigree in golf and sports titles (International Open Golf Championship, Ryder Cup). The core design duo, David Harrison and Ron Oulton, leveraged their programming and design expertise to pivot into the burgeoning “thinking person’s strategy” genre, drawing clear inspiration from Mike Singleton’s genre-blending masterpiece Midwinter (1989) and the political simulation Ashes of Empire (1992). Their vision was explicitly pitched as a more focused, stats-driven successor to those classics, and in the same vein as Shadow President (1993), which tackled global diplomacy with spreadsheet-like intensity.

The year 1994 was a peak period for complex PC strategy. The CD-ROM had become a viable distribution format, allowing for ample storage of data, digitized images, and (often awkward) full-motion video. Central Intelligence was a CD-ROM title, and its data reflects this: a massive, detailed world map of the fictional Caribbean island of Sao Madrigal, populated by over 1,360 individually simulating NPCs, each with routines, loyalties, and affiliations. This scale was technically impressive for the era, a “living world” simulated in persistent real-time. However, this ambition was shackled to the technological and design paradigms of DOS. The interface was built for mouse and keyboard but lacked the ergonomic foresight of contemporaries like Sid Meier’s Covert Action (1990), which balanced detail with tactile, actionable feedback. Ocean Software, a publisher known for licensed games and budget titles, may have provided distribution heft but likely offered insufficient resources for the rigorous user experience (UX) polishing that Central Intelligence desperately needed.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Morality of “Democratic” Intervention

The game’s narrative is a cold, calculated premise straight from a late-Cold War thriller. The U.S. has sent a CIA chief (the player) to Sao Madrigal, a resource-rich island whose fascist dictator, “El Dictador,” has seized Western assets and aligned with China. An overt invasion is politically toxic; the dictator enjoys popular support for his anti-imperialist stance. Thus, a clandestine operation is authorized: “organize the recuperation of democracy, by any means necessary,” in partnership with the exiled leader of the prior democratic government.

This premise is a dense tapestry of thematic ambiguity. The stated goal is “democracy,” but the methods are the toolkit of tyranny: propaganda, bribery, subterfuge, assassination, and blackmail. The game forces the player to confront the moral hypocrisy of using illiberal means to achieve liberal ends—a tension rarely acknowledged in the jingoistic action games of the era. The factions you manipulate—angry students, urban guerrillas, political parties—are not mere units but simulated entities with their own agency. You can support them overtly or covertly, a distinction that impacts their perceived legitimacy and the island’s population loyalty. The narrative is not told through cutscenes or dialogue trees, but emergent from the systems. The story of your campaign is written in the loyalty shifts on the map, the assassinated generals, the bombed infrastructure, and the final, triumphant or tragic, uprising. This is narrative as a consequence of gameplay, a hallmark of deep simulation that would not become commonplace for another decade.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Feast of Detail, a Famine of Feedback

At its core, Central Intelligence is a turn-less, real-time strategic simulation. The main interface is a top-down satellite view of Sao Madrigal. The player’s primary verbs are: Zoom, Select an Agent, Assign a Mission to a specific building, and Observe the resulting cascade of effects.

-

Agent Branches: Your CIA assets are divided into three specialized branches, each with a suite of actions:

- Political: Diplomacy, bribing officials, gathering intelligence (spying).

- Propaganda: Printing leaflets, hijacking TV broadcasts, spreading disinformation to sway public loyalty.

- Military: Sabotage, assassinations, arms trafficking to rebel factions.

- Crucially, the game discourages a purely military solution. Winning requires building a broad coalition of opposition factions, making political and propaganda actions equally, if not more, vital.

-

The Living World & Core Loop: The “living world” is the game’s most celebrated feature. As critic Computer Gaming World noted, the island is “so seductively realized, that you find yourself wanting to shrink and actually walk those colorful streets.” Each of the 1,360 NPCs has a daily routine: they go to work, visit bars, sleep, and can be arrested. Their individual loyalties (blue for pro-democracy, red for pro-dictator) are aggregated at the building and district level. The core loop is a cycle of: Intelligence Gathering (spying on buildings to see occupants and contents) → Resource Allocation (sending agents with specific orders) → Systemic Reaction (watching loyalty numbers shift, events fire, factions gain/lose influence) → Strategic Adaptation. This creates immense strategic freedom, as lauded by player reviewer AtomicHorse: “You can really try to achieve your objective… from assassination… to using rebels to storm the Presidential Palace.”

-

The Crippling Flaws: This systemic depth is consistently undermined by a user interface of legendary infamy.

- Cumbersome Navigation: The agent assignment process is a multi-step, non-intuitive slog. As AtomicHorse detailed, canceling an agent’s orders requires a labyrinthine return to menus; there is no right-click shortcut. This turns every micro-decision into a chore.

- The One-Save Limitation: The game allows only a single save slot. In a long, complex, real-time campaign where a single misclick can doom your operation, this is either a cruel design choice or a staggering oversight. It forces players to either play with permanent consequences or, more likely, quit in frustration.

- No Tracking Tools: The game provides almost no in-game tools to track agent locations, mission status, or long-term trends. The population loyalty is shown, but the why is buried in text logs. As AtomicHorse states, “you pretty much HAVE to keep your own notes on your computer or on papers IRL.” This externalizes the meta-game, breaking immersion and demanding a historian’s diligence from the player.

- Feedback Paucity: Outcomes are often delivered as dry text reports (“Agent X successfully bribed Official Y”) rather than visual or auditory feedback. This lack of immediate, visceral consequence makes the gameplay feel abstract and “dry,” as noted by My Abandonware and Golden Age of Games. The comparison to Twilight 2000 or Covert Action, which featured action sequences, is damning.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Immersive Scale, Uninspired Execution

Central Intelligence‘s world is a study in contrasts. The conceptual scale is immense. Sao Madrigal is a large, varied island with distinct districts—urban centers, rural farmland, military barracks, rebel hideouts. The top-down satellite view, while primitive by today’s standards, effectively communicates this geography. The ambition to simulate a complete society is palpable.

The visual presentation, however, is where that ambition falters. The game is built from static, low-resolution digitized photographs of locations and character portraits. Critics were merciless: PC Joker called them “grobpixelig” (coarsely pixelated); Power Play dismissed the “statischen Digi-Bildchen” (static digital pictures) and “animationsamputierte Mickergrafik” (animation-amputated mediocre graphics), comparing its intro (by famed artist Bob Wakelin) favorably to the actual gameplay, calling the disconnect “schleierhaft” (obscure). The aesthetic is less “cyberpunk intelligence hub” and more “vacation photo slideshow,” which utterly fails to convey the tension and grit of a covert operation. This “dryness” saps the thematic urgency.

Sound design is equally minimal, consisting largely of basic interface beeps and perhaps a few ambient loops, easily forgotten. The overall atmosphere is one of clinical detachment—appropriate for a intelligence briefing, but fatal for player engagement. You are a analyst, not an operative. The world is vast and detailed, but presented as a spreadsheet with pictures, not a place with soul.

Reception & Legacy: From W niche Curiosity to Abandonware Legend

Central Intelligence was dinnerly panned upon release. Its MobyGames average critic score of 51% masks a terrifying range: from Power Play‘s scorching 18% (awarding it “Worst Game of 1994”) to MikroBitti‘s cautiously optimistic 70%. The common refrain was a schism between premise and execution. Computer Gaming World‘s review perfectly captured this paradox: “It’s too bad really, and a fault that could be corrected, albeit not with an uploaded patch. CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE is indeed a feast of detail – but then, revolution is not a dinner party.”

Commercially, it sank without a trace. RISC vanished, and Ocean moved on. For years, it was a forgotten abandonware title, sought only by niche strategy collectors and those intrigued by its audacious design document. Its legacy is paradoxical:

- As a Failure: It became a textbook example of how overwhelming systemic complexity and poor UX can neuter a brilliant core concept. Its most lasting influence may be as a warning to designers about the necessity of information design and ergonomics.

- As a Cult Artifact: A small, passionate community recognized its genius beneath the grimy interface. The player review on MobyGames (the only substantial one) calls it a “hidden gem,” praising the “living world” and “freedom,” while begrudgingly admitting the UI forces note-taking. The Steam community guide (despite being removed) aimed to provide a manual and walkthrough, evidence of a persistent desire to conquer its barriers.

- As a Historical Curiosity: It sits at a crossroads. It inherits the open-ended, systemic espionage of Midwinter but strips away the action-adventure elements. It anticipates the deep, data-driven political simulations of later titles like Tropico (though with a far grimmer realism) and the obsessive micromanagement of modern grand strategy. Its attempt to simulate a full society of autonomous agents foreshadows the likes of Dwarf Fortress or RimWorld, but without their accessible visualization tools.

Its re-release on Steam in 2018 by Piko Interactive (and later Ziggurat) is less a celebration and more a preservation effort—a digital museum piece for those willing to grapple with its idiosyncrasies. The modern player score on platforms like Steambase hovers around 43/100 (Mixed), reflecting the same divide: admiration for its scope, frustration with its interface.

Conclusion: The Scholar’s Game, Not the Soldier’s

Central Intelligence is not a good game by any conventional metric. Its interface is a masterclass in frustration, its feedback loops are opaque, and its presentation is dully academic. It demands more from the player—in terms of note-taking, patience, and interpretive labor—than almost any mainstream strategy title of its era or since.

And yet, it is a profoundly important and fascinating artifact. Its vision of a fully simulated, autonomous world where conflict is waged through influence, loyalty, and information remains staggeringly ambitious. The freedom it offers—to塑造 (shape) a revolution through a thousand subtle cuts rather than a single military thrust—is unmatched in its period. It is a game that trusts the player to be a historian and a spymaster, not just a general.

For the professional historian, Central Intelligence is a vital primary source: a snapshot of 1994’s techno-utopian dreams for interactive simulation, and a brutal lesson in the gulf between systemic ambition and playable reality. For the curious modern player, it is a punishing but potentially rewarding excavation. It asks you to see past its DOS-era ugliness and its cruel interface, to engage with one of the most depth-rich, morally complex, and politically resonant strategy worlds ever built—a world that, for all its flaws, still feels more alive and consequential than the polished, simplified proxies of modern gaming.

Final Verdict: A broken, Byzantine, and often infuriating masterpiece of simulation design. It is a game that history should remember not for how many enjoyed it, but for how much it dared to imagine—and for the hard, necessary lessons its failures taught the industry about the sacred covenant between a complex system and the human operating it.