- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: eGames, Inc.

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Chess

Description

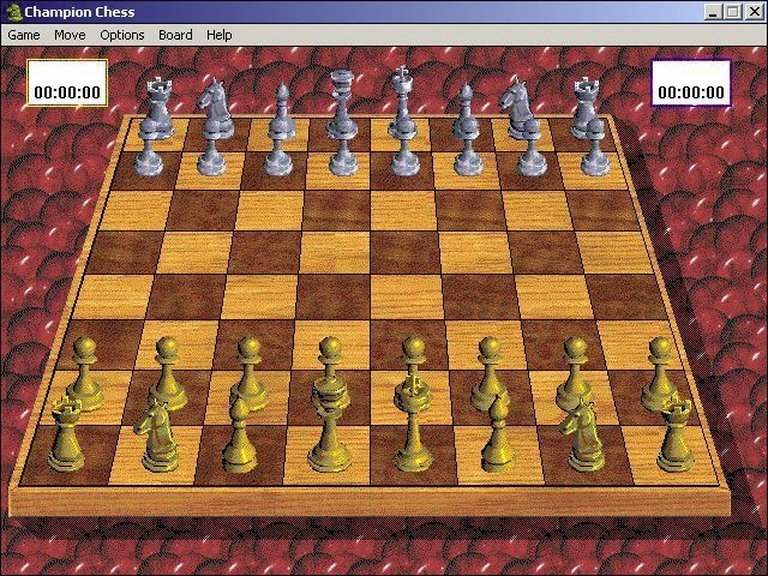

Champion Chess is a strategy chess game released in 2000 for Windows, offering both single-player and two-player modes. The game features mouse-controlled gameplay with a variety of customizable 3D chess pieces, boards, and backgrounds, alongside a traditional 2D mode. Players can save games in progress, receive move suggestions, and print move histories, though it lacks a library of historic games or game import functionality.

Champion Chess Free Download

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Champion Chess: A Digital Artifact from the Dawn of the 3D Strategy Era

In the vast annals of video game history, certain titles are remembered for their revolutionary impact, their genre-defining narratives, or their technical marvels. Others, like eGames’ 2000 release Champion Chess, serve a different, yet equally vital, purpose: they are perfect time capsules, crystallizing a specific moment in technological and design evolution. This is not a review of a forgotten masterpiece that redefined its genre, but rather a deep archaeological dig into a modest, functional product that represents the ambitions and limitations of PC gaming at the turn of the millennium. Our thesis is that Champion Chess is a historically significant artifact not for what it achieved, but for what it attempted to be—a bridge between the abstract, 2D world of classical chess software and the burgeoning, immersive potential of 3D graphics for the everyday user.

Development History & Context

To understand Champion Chess, one must first understand its publisher, eGames, Inc. Active in the late 1990s and early 2000s, eGames operated in a specific niche: they were purveyors of affordable, often budget-tier, software primarily sold in big-box retail stores. Their catalog was filled with casual titles, puzzle games, and simple utilities aimed at the burgeoning home PC market. They were not aiming for the hardcore strategy enthusiast who might seek out a premium product like Chessmaster. Instead, their target audience was the family or casual user who wanted a visually appealing digital chess set.

The development team, as credited, was strikingly small: just two individuals, Ross Roberts (programming) and Tom Carter (art). This minimalist credits list speaks volumes about the project’s scale and the constraints under which it was built. The year 2000 was a fascinating juncture in technology. 3D acceleration was becoming standard in gaming PCs, but developers were still grappling with how to implement it effectively outside of first-person shooters and racing games. The vision for Champion Chess was likely born from this context: a desire to leverage this new 3D capability to dress up one of the world’s oldest games, to make it feel “modern.”

The gaming landscape was one of rapid transition. While hardcore gamers were marveling at the likes of Deus Ex and The Sims, a massive casual market was hungry for accessible entertainment. Champion Chess sits squarely in this latter camp. It wasn’t competing with the deep AI and extensive tutorials of its more expensive counterparts; it was competing for attention on a Walmart shelf, promising a flashy 3D experience that physical chess sets could not offer. Its development was likely driven by a pragmatic vision: create a functional, visually customizable chess game with a low barrier to entry and a budget price point.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

As a pure simulation of an abstract strategy game, Champion Chess possesses no narrative, no characters, and no dialogue in the traditional video game sense. However, to dismiss its thematic elements would be to overlook a crucial part of its design philosophy.

The “narrative” of Champion Chess is one it creates through environmental implication. By offering a “variety of 3D different chess pieces, boards, [and] backgrounds,” the game allows the player to construct their own thematic context for the battle of wits about to unfold. Will this match be a classical encounter in a traditional wood-paneled study? A clash of ornate, medieval armies on a stone dais? Or perhaps a more abstract, futuristic battle on a minimalist grid? The power of choice, however limited, injects a subtle layer of thematic role-playing.

The underlying theme is one of elevation and tangibility. For centuries, chess existed as wood on a board. Digital chess initially translated this into pixels on a screen. Champion Chess’s theme is the translation of that intellectual exercise into a seemingly physical, tactile space. The 3D perspective (1st-person, according to its specs) isn’t just a visual trick; it’s an attempt to theme the game around presence and immersion, to make the player feel as if they are leaning over a real board, contemplating a real move. The ability to print the move history further reinforces this theme, connecting the digital action back to the physical world—a record of a battle that, in the game’s fiction, felt real.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its absolute core, Champion Chess is a faithful digital implementation of the standard rules of chess. The core gameplay loop is immutable: players take turns moving pieces with the goal of checkmating the opponent’s king. Input is handled exclusively via the mouse, ensuring accessibility.

The game’s mechanics can be broken into two distinct layers:

1. The Foundational Chess Engine: The AI that powers the computer opponent is the heart of any chess game. The provided materials offer no detail on its strength, opening book size, or configurability. The presence of a “suggest next move” feature indicates a helper function was implemented, a basic aid for novice players. The glaring omission, as noted in the description, is the “library of historic games and no game import function.” This marks a significant mechanical shortcoming compared to more serious chess software, locking players into their own games without the ability to study famous matches or analyze externally created game files.

2. The Presentation Layer: This is where Champion Chess attempts to innovate. The mechanics of presentation are a key system:

* 3D Visualization: The ability to render the board and pieces in 3D from a first-person perspective was its primary selling point. This system allows for spatial awareness and a sense of depth absent from 2D chess games.

* Customization System: The selection of different boards and pieces acts as a cosmetic progression or customization system. While it doesn’t affect the core rules, it provides a meta-goal and a reason to explore the game’s options.

* 2D Fallback: The inclusion of a “2D mode” is a crucial and thoughtful mechanical option. It acknowledges that the 3D view, potentially confusing or harder to parse for some players, is a feature and not the core experience. This ensures functionality isn’t sacrificed for flair.

The UI appears to be minimalist, built around mouse controls. The ability to save a game in progress is a fundamental and expected mechanic for any digital chess implementation. Overall, the gameplay systems are functional and accessible but lack the depth and features (analysis modes, difficulty scaling, tutorials) that would appeal to serious chess aficionados.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The “world” of Champion Chess is not a continuous geography but a series of discrete tableaus. The art direction, helmed by Tom Carter, was tasked with creating these distinct visual environments. While the source material doesn’t detail the specific themes, we can infer from the era that these likely ranged from classic (e.g., polished oak boards, ivory and ebony pieces) to the fantastical (e.g., crystal pieces, marble boards) or even the sci-fi (e.g., neon grids, metallic pieces).

The atmosphere is therefore not unified but selectable. A player can choose between the quiet, solemn atmosphere of a classical setting or the cooler, more calculated atmosphere of a futuristic one. The first-person perspective is the most critical artistic choice, as it directly builds the world around the player, placing them not as an omniscient god above the board, but as a participant seated at the table.

The sound design is another complete unknown from the source, but its role would be paramount in selling the tactile fantasy. The click of a piece on a square, the sound it makes when capturing an opponent—these audio cues are essential for feedback and for building the illusion of physicality. The absence of any mention of a soundtrack suggests the experience may have been accompanied only by these diegetic sound effects, reinforcing the focused, cerebral tone of a real chess match.

Reception & Legacy

The commercial and critical reception of Champion Chess is, according to the historical record, virtually non-existent. With no critic reviews archived and only a single user rating on MobyGames (a 4.2/5, though based on zero written reviews), it exists in a void of historical silence. This obscurity is its most defining characteristic. It was not a commercial bomb that made headlines, nor was it a breakout hit. It was a quiet, budget-tier release that found its way onto a limited number of hard drives, likely through bargain bins or as an impulse purchase.

Its legacy is not one of direct influence but of representation. Champion Chess represents a entire class of software from the early 3D era: low-budget, often independently developed titles that sought to capitalize on new graphical capabilities to refresh familiar concepts. It is a precursor to the thousands of 3D casual games that would flood digital marketplaces like Steam in later decades.

Its true legacy is as a museum piece. It shows us how small teams attempted to navigate the technological shift to 3D. It highlights the market gap between hardcore sims and casual experiences. For game historians, it is a perfect example of the “long tail” of game development—the countless minor titles that, together, form the true fabric of any era in gaming, far more so than the few legendary classics we all remember.

Conclusion

Champion Chess is not a great game in the sense that it pushed artistic boundaries or achieved unparalleled depth. Judged by the standards of chess software, it was a bare-bones, feature-light entry overshadowed by more robust competitors. However, to dismiss it on those terms would be to miss its historical value entirely.

As a digital artifact, it is a fascinating snapshot. It captures the moment when 3D graphics became a marketable feature for even the most mundane software. It exemplifies the output of publishers like eGames who served the overlooked casual market. The work of its two-person team embodies the DIY spirit of the period. Champion Chess’s definitive place in video game history is secured not on a podium, but in the archives—a humble, functional, and perfectly representative relic of the PC gaming world at the dawn of the 21st century. It is a champion only of its own specific time and place, and for that, it deserves to be remembered.