- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Empire Interactive Europe Ltd., Idigicon Limited

- Developer: MDickie Limited

- Genre: Action, Sports

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Boxing, Career mode, Character Creation, Multiple match types, Random events

- Average Score: 72/100

Description

Championship Boxing is a single-player 3D boxing simulation that offers two main modes: ‘Boxer’s Story,’ where players follow the career of Adam Bradbury from gym workouts to championship fights, and ‘Boxer’s Fantasy,’ allowing free matches with any boxer. The game features Normal, Hardcore, and Technical match types, unpredictable ‘miracles,’ and a boxer editor for creating up to thirty custom fighters, all set in boxing rings and gym environments.

Where to Buy Championship Boxing

PC

Championship Boxing Cracks & Fixes

Championship Boxing Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (100/100): Almost everything. it has a nice little editor and a story

thesportster.com (37/100): Mike Tyson Heavyweight Boxing fell short with critics due to poor controls and graphics, scoring a low 37 out of 100 on Metacritic.

myabandonware.com : thanks for the full version of this game i love it!

metacritic.com (79/100): An ode to the sweet science, and it’s one of the most intricate and accurate sims of the sport ever released.

Championship Boxing (2002): A Solemn Journey Through the Forgotten Trenches of PC Pugilism

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine

In the vast, digitized museum of sports video games, certain titles stand as monolithic pillars—Fight Night, Punch-Out!!, the Rocky adaptations. Then there are the ghosts: games that flicker in the archival corners of sites like MobyGames and My Abandonware, known to a handful of nostalgic collectors and hardcore genre archivists. Championship Boxing (2002), developed by the enigmatic Mat Dickie under his MDickie Limited banner, is one such ghost. It is not a game that defined an era, nor one that shattered sales records. Instead, it is a profound and telling artifact of a specific moment: the early-2000s PC indie scene, where a single developer could produce, publish, and distribute a full 3D sports simulation from a bedroom workstation. This review posits that Championship Boxing is less a failed contender and more a time capsule—a raw, unvarnished look at the ambition and constraints of its time. It is a game that wears its heart on its sleeve, offering a surprisingly robust creation suite and a quirky, unpredictable simulation core, all while struggling under the weight of technical limitations and a genre sprinting toward graphical fidelity. To understand Championship Boxing is to understand the658 DIY spirit that preceded the democratization of game development tools.

Development History & Context: The One-Man Gym

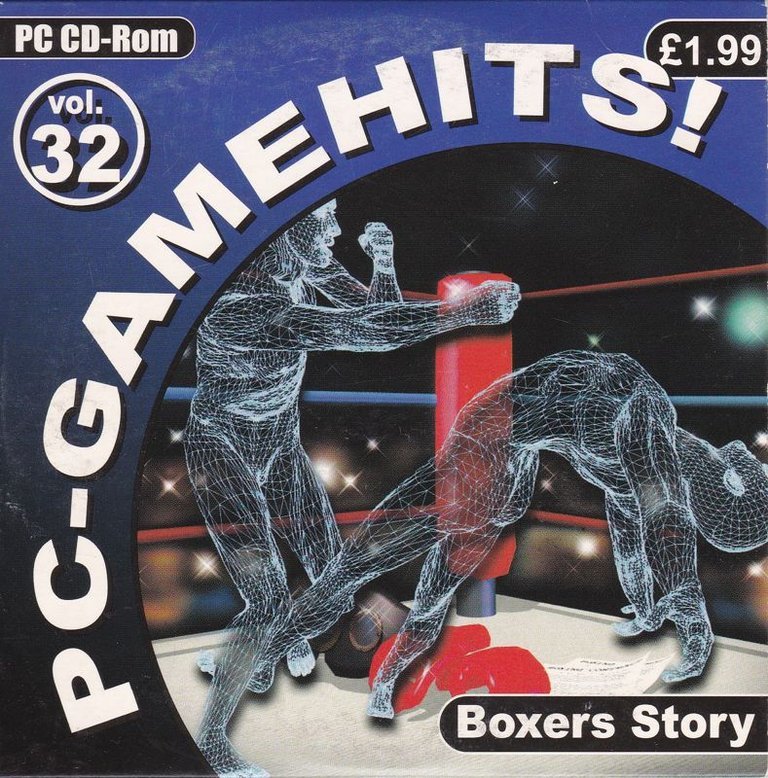

The story of Championship Boxing is intrinsically the story of Mat Dickie, a developer whose name is synonymous with a peculiar niche of wrestling, MMA, and boxing management sims. The game’s origin, as noted on its MobyGames entry and linked developer site, is telling: it “started out being called ‘Rocky’ after the movie series.” This was not a licensed product but an homage, a freeware project Dickie created. Its trajectory—from the free “Rocky” to the commercially published “Boxer’s Story,” then released as “Arcade Boxing” before settling on the final Championship Boxing—reveals a project in constant negotiation with publishers Idigicon Limited and Empire Interactive Europe Ltd. This was the era of the “budget label” publisher, where companies like Idigicon would acquire promising indie titles, provide minimal polish and distribution, and slot them into retail bins or later, compilation discs like 10 Krazy Kids PC Games Vol. 3 (2008).

Technologically, 2002 was a pivot point. The PlayStation 2 and Xbox were in their prime, pushing polygons and texture detail. The PC, however, remained a wild west where a talented programmer could still produce a functional 3D title with tools like Visual Basic and early DirectX (likely 7 or 8). Championship Boxing reflects this: it is a 3D game, but its “bad graphics,” as succinctly put by a user reviewer, are not a stylistic choice but a necessity. Models are blocky, animations are stiff, and the ring environment is sparsely detailed. This was the cost of a solo developer tackling 3D rendering, physics, and game logic alone. The gaming landscape was dominated by EA’s Fight Night 2002 and the Knockout Kings series—high-budget, licensed behemoths. Championship Boxing existed in their shadow, not as a rival, but as a defiantly independent, rules-light alternative for the PC sports fan who craved simulation depth without the corporate gloss.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Ballad of Adam Bradbury

There is no choice. There is no create-a-fighter for the main “Boxer’s Story” mode. You are Adam Bradbury, and your journey from gym workouts to world title is a linear, text-driven narrative told through pre-fight and post-fight screens. This is the game’s most fascinating structural choice. Unlike the filmic arcs of the Rocky games or the career managers of Fight Night, Championship Boxing presents a pure, unadulterated sports narrative. The story is a classic boxing archetype: the hungry up-and-comer, the tough journeyman, the formidable champion. The “dialogue” is minimal, likely brief descriptions of opponents and their reputations.

Thematically, the game is about progression and resilience. The first two “workout” matches in the gym serve as a brutal tutorial, a baptism by fire that immediately establishes the game’s punishing difficulty. You are not a chosen one; you are a working boxer. The theme of “miracles”—rare events where a lucky punch lands, a fighter gets a second wind, or a mutual knockout occurs—injects a dose of chaotic, narrative-worthy unpredictability. These are not just mechanics; they are the game’s equivalent of a Hollywood script twist, the moment where the underdog’s wild swing connects perfectly. The narrative thus becomes a collaborative effort between the player and the game’s RNG, crafting unique stories of comeback victories and shocking upsets. It’s a thematic echo of boxing’s own mythology: that any given night, one man can change his destiny with a single punch.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Unforgiving Science

Championship Boxing is an action-sports hybrid, but its soul lies in its match types and simulation quirks. The three match formats reveal a designer thinking deeply about boxing’s different rhythms:

- Normal: The standard. Three-minute rounds, a three-knockdown-per-round rule, and a decisive finish (KO or TKO). This is the “sport” mode.

- Hardcore: A pure, grueling war of attrition with no rounds. This is the “brutal” mode, testing stamina management and sheer will.

- Technical: A five-round points decision if no knockout occurs. This mode rewards defensive boxing and accumulation, though the game’s scoring system is opaque, a common trait in older boxing sims.

The combat itself is real-time, third-person. Controls are redefinable, a crucial feature given the keyboard-centric design common in PC sports games of the era. Punching, blocking, and movement are mapped to keys, requiring dexterity. The game’s famed difficulty (“a bit hard”) stems from a combination of factors: a relatively slow character response, a stamina bar that depletes rapidly with offense, and AI that is relentlessly aggressive. Winning requires patience, counter-punching, and strategic use of the “miracles” mechanic—sometimes your only hope is a lucky shot when cornered.

The Boxer Editor is the game’s undisputed star feature. Allowing up to 30 custom fighters, it provides a canvas for the player’s imagination. While the exact stat spread isn’t detailed in the sources, its existence and praise (“has a nice little editor”) suggest a level of customization that was impressive for a budget title. It transforms the game from a linear story into a sandbox for fantasy matchups—a full decade before modes like Fight Night Round 4‘s “Fan Request” feature. The inability to delete created boxers (only replace them) is a curious, likely technical limitation, forcing a “slot management” mindset that adds an odd, archival layer to creation.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Gritty Aesthetic

The world of Championship Boxing is one of stark minimalism. There are no licensed venues, no real cityscapes. The ring is a generic blue-and-red canvas in a dimly lit arena, the crowd a low-poly blob of colors. This austerity is both a limitation and a focus. With no real-world landmarks to model, the game’s visual attention is solely on the two combatants. The character models, while “bad” by modern standards, are serviceable 3D mannequins. The animation is functional—jabs, hooks, uppercuts, and the all-important knockdown sequence are clearly readable, which is paramount for gameplay. Damage is shown via texture swaps: a gradually reddening face, swelling eyes.

Sound design, credited to Andrew Wilson, is pure early-2000s MIDI-inspired synthesis. The music is likely an energetic, looping track meant to evoke excitement, while sound effects are tinny punches, grunts, and the bell. The atmosphere is not one of televised spectacle but of a raw, underground fight club. This aesthetic reinforces the game’s themes: this is not the glamour of HBO or Showtime; it’s the sweaty, fluorescent-lit gym or the smoky local hall. The “bad graphics” are not an attempt at realism but a pragmatic acceptance of a low-budget 3D engine, creating a unique, almost dreamlike visual language that is now part of its retro charm.

Reception & Legacy: The Quiet Contender

Upon its December 2002 release, Championship Boxing occurred in a critical vacuum. It received no coverage in major gaming magazines of the era. Its only listed review on MobyGames is a retrospective 5/5 score from 2025, where user “Ramim” lauds its editor and story, citing nostalgia as the primary lens. This tells the entire story of its commercial and critical journey: it was a footnote, sold in bargain bins and compilation packs, discovered by a few players who valued its strange depth over its technical rough edges.

Its legacy is twofold. First, as a historical document: it represents the last gasp of a certain kind of PC sports game—the single-developer, simulation-first project that prioritized systemic depth (the “miracles,” the detailed match types, the editor) over presentation. It predates the explosion of user-friendly modding communities and digital storefronts. Second, and more concretely, it is a foundational stone in the eclectic library of Mat Dickie. The design philosophies here—accessible but deep simulation, a focus on user-generated content, and a willingness to embrace quirky randomness—would be refined in his later, similarly cult-favorite wrestling titles (Wrestling MPire, Wrestling Encounter).

In the grand taxonomy of boxing games, it stands apart from both the arcade frenzy of Punch-Out!! and the gritty simulation of later Fight Night titles. It is closer in spirit to the meticulous, menu-driven Title Bout Championship Boxing sims, but with real-time combat instead of turn-based calculation. Its influence is negligible in the mainstream, but for those tracing the lineage of indie sports development, it is a crucial, humble milestone.

Conclusion: The Unkempt Heavyweight

Championship Boxing is not a forgotten masterpiece. It is a flawed, sometimes frustrating, and technically dated game. Its graphics are crude, its interface dated, and its single-player story is a bare-bones string of bouts. Yet, to dismiss it is to miss its vital character. In an era increasingly defined by licensed rosters and cinematic presentation, Championship Boxing asks a simpler question: “What if the focus was on the fight itself—its unpredictable rhythm, its capacity for miracle, and the player’s ability to shape it?” Its robust fighter editor and trio of match formats grant it a creative longevity that many polished, “better” games lack.

Its true verdict lies in its survival. It is preserved on abandonware sites, played by enthusiasts, and remembered with a specific fondness. It is a game that understands the elemental truth of boxing: that the story is written in the ring, one punch at a time, and that sometimes, against all odds, the underdog lands the lucky shot. For that, Championship Boxing earns its place in the history books—not as a champion, but as a resilient, endearingly rugged workhorse from a bygone era of PC sports development. It is, in the truest sense, a 7-round decision victory on points: not overwhelmingly dominant in any one category, but persistent, versatile, and deeply committed to its own unique rule set.