- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Gilles Khouzam

- Genre: Board game, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP

- Gameplay: Board game

- Average Score: 75/100

Description

Chinese Checkers is a strategic board game of German origin, popularized in the U.S. as a simplified variant of Halma, played on a star-shaped hexagram board. The objective is to move all of one’s pieces (typically 10 or 15) from their starting corner across the board into the opposite ‘home’ corner using single-step moves or multi-hop jumps over other pieces—no captures occur, and hopped pieces remain in play. Designed for 2–6 players, the game emphasizes tactical movement and speed, with turns proceeding clockwise, and victory going to the first player to fully occupy their home. The 1995 Windows release by Gilles Khouzam adapts this classic for digital play, supporting multiplayer over LAN or internet with mouse-driven gameplay and no AI opponents.

Gameplay Videos

Chinese Checkers Free Download

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (70/100): The best PC based chinese checkers game I have ever played!

Chinese Checkers: Review

Introduction

In the vast and varied landscape of digital adaptations of board games, few titles hold as much cultural irony, historical intrigue, and overlooked brilliance as Chinese Checkers (1995, Windows), a shareware multiplayer translation of the classic Stern-Halma game. Conceived not in China, nor by Chinese designers, but in Germany in 1892, and later rebranded for American audiences by the Pressman brothers in 1928, Chinese Checkers is a textbook example of how a game’s identity can be reshaped—and often distorted—by marketing, colonialism, and cultural exoticism. The 1995 Windows version developed by Gilles Khouzam and released as shareware represents a critical inflection point in the digital evolution of abstract strategy games, one that foreshadowed the rise of internet-based, peer-connected multiplayer experiences in an era before Xbox Live, Steam, or broadband ubiquity.

This review presents a comprehensive, historically grounded, and mechanically dissected analysis of the 1995 Windows adaptation of Chinese Checkers, examining its significance not merely as a digital version of a parlor game, but as a pioneering experiment in networked multiplayer board gaming, a cultural artifact of early internet accessibility, and a testament to the enduring power of minimalist, multiplayer-first design. Born at the dawn of the Windows 95 revolution, this game was conceived as a socially connected digital experience when that concept was still in its infancy—offering peer-to-peer, LAN, and early internet play at a time when most computer games still defaulted to local multiplayer or AI opponents.

Thesis: Despite its lack of single-player AI, minimalist aesthetics, and near-total absence from mainstream critical discourse, Chinese Checkers (1995) is a landmark in digital board gaming history—a beautifully simple yet technically ambitious network-first reimagining of a Western reinterpretation of a misattributed ‘Oriental’ game. Its legacy lies not in graphical splendor or narrative depth, but in its foregrounding of human competition in a digital space, its purity of mechanics, and its unintentional embodiment of the cross-cultural confusions and marketing fictions that have come to define popular understandings of global game traditions.

Development History & Context

The Man Behind the Pins: Gilles Khouzam and Shareware in the Mid-90s

In 1995, as Microsoft launched Windows 95 and the world began its tentative march toward networked computing, Gilles Khouzam, a now largely forgotten developer, created a minimalist yet technically sophisticated version of Chinese Checkers for the nascent Windows platform. Available as shareware (101 KB) and downloadable from websites like MyAbandonware and MobyGames, the game was a one-person effort—a rarity in 1995, when even small games often involved teams of five or more for graphics, sound, programming, and design.

Khouzam’s vision was clear: to create a pure multiplayer adaptation of Chinese Checkers, one that leveraged Windows 95’s native networking stack (NetBEUI, IPX, and early TCP/IP via dial-up or LAN) to enable real-time, peer-to-peer gameplay. This was a radical departure from the norm. Most board games of the era—such as ImagiSoft’s Chinese Checkers (1991, DOS)—included AI opponents, tutorial modes, sound options, and graphical flourishes. Khouzam’s version, by contrast, drew a firm line: this was not a game with multiplayer—it was multiplayer, nothing more.

Technological Constraints and Ambition

The game was entirely mouse-driven in gameplay, but required keyboard input for setting up network connections—a telling hybrid of interface design that reflected the technological transition of the time. While the mouse allowed intuitive piece selection and animated jumping sequences, the keyboard was essential for inputting server addresses, usernames, and protocol settings—making the game a bridge between tactile interaction and the textual complexity of early networking.

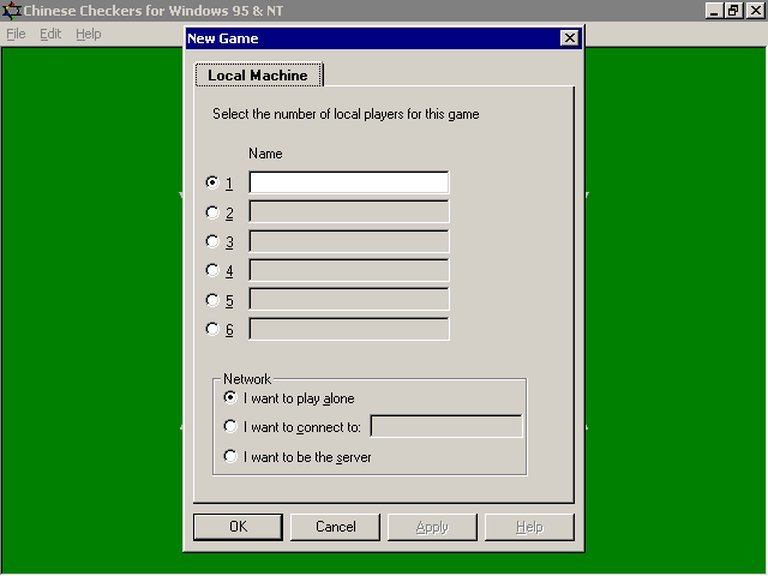

Running on Windows 95 & NT, it supported 1–6 players, with connection modes including Internet (via direct IP or early chat-room launchers), LAN, and serial link—a feature list that was astonishingly forward-thinking for a 101 KB download. While it lacked AI, the game offered real-time chat during matches, dynamic turn indicators, and semi-persistent lobbies—all without requiring a central server, a rarity in an era before peer-to-peer frameworks like ZeroMQ or WebRTC.

The 1995 Gaming Landscape: A Crossroads for Board Games

In 1995, the gaming world was bifurcating. On one side: the rise of CD-ROM-driven, multimodal titles like Myst, Wing Commander III, and Command & Conquer—games with budgets in the millions, cinematic cutscenes, and orchestral scores. On the other: the resurgence of abstract strategy and card games in digital form, often distributed via shareware or online FTP sites. Games like Frischklatsch (a German Scabble variant), Chessmaster 5000, and Hearts clones were gaining popularity on BBSes and early online services like AOL and CompuServe.

Chinese Checkers stood at the intersection of these trends. It was not a console port, nor a flashy graphical experience. It was a digital purist’s board game—a software implementation that stripped away everything but the core mechanics of jumping, positioning, and human competition. Its shareware model (users could try it free, buy a key for full features like custom colors or persistent profiles) reflected the ethical, grassroots distribution ethos of early internet culture—long before microtransactions or pay-to-win.

Importantly, it anticipated the future of online multiplayer by making human interaction the only gameplay mode. In an era when Tetris and Doom dominated multiplayer discourse, Khouzam dared to make a game where the AI was not absent—it was irrelevant.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

No Story, All Theme: The Irony of “Chinese” in a German Game

Chinese Checkers, as a concept, is devoid of narrative. There are no characters, no dialogue, no cutscenes. Yet, its thematic undercurrents are profound, even performative, and reveal a complex layer of cultural appropriation, market-driven myth-making, and linguistic colonialism.

The Naming Is the Narrative

The game’s name is itself a fiction—marketed into existence. As revealed by the source material from Wikipedia, The Grunge, and Medium articles, “Chinese Checkers” was never Chinese. Invented in Germany in 1892 as Stern-Halma (“Star Halma”), it emerged from the older American game Halma (1883), itself a variant of English ludo. The six-pointed star board, while visually striking, has no traditional Chinese aesthetic roots—stars were not a common motif in Xiangqi (Chinese chess) or Chinese games, which favor grids and circles.

The name “Chinese Checkers” was a pure marketing invention by Bill and Jack Pressman in 1928, as a rebrand of their “Hop Ching Checkers.” As media scholar Philip Fung argues in his Medium piece, “When ‘Chinese’ was code for ‘Bizarre,’” the term “Chinese” in early 20th-century Western culture connoted exoticism, mystery, and the absurd—not authenticity. “Chinese Checkers,” “Chinese Fire Drills,” “Chinese Ollies”—these were not references to Chinese culture but to culturally appropriated shorthand for the strange, the unorthodox, the comically alien.

In this context, Khouzam’s digital adaptation becomes a silent, uncredited participant in this linguistic farce. The game makes no attempt to deconstruct, explain, or even acknowledge the misattribution. There are no historical blurbs, no translations of tiaoqi (跳棋, “jump chess”), no references to the game’s German origins. The board is red, green, blue, yellow, purple, and cyan—not red-and-gold dragons, not pagodas, not calligraphy. It’s as if the developers, aware of the game’s Western roots, intentionally held the mythology at arm’s length, letting the mechanics speak.

Themes of Strategy, Repetition, and Human Foible

Yet, despite its lack of narrative, the game emits a silent theme: the tension between planning and improvisation, between control and chaos. The board—a six-pointed star—is a closed system, a finite space where every move by one player alters the options of all others. The game is a study in emergent narrative: alliances form (among 6-player teams), betrayals happen (as players use others’ pieces to build “ladders”), and ego-driven blunders shape outcomes.

The lack of AI forces full accountability to human error. There’s no “difficulty level.” The challenge isn’t from a perfect machine—it’s from a real person who gets tempted by a 7-hop chain when a 2-hop might win the game. This is the true psychology of the game: not about outsmarting a program, but about reading another mind in real time.

Moreover, the variation in piece distribution (10, 15, or 21 pieces depending on player count) and starting configurations (mirrored, staggered, shared triangles) introduces tacit themes of fairness, access, and balance—questions that were later formalized in modern game theory discussions about board symmetry and player equity.

In essence, Chinese Checkers (1995) is a narrative of unspoken competition, where the only dialogue is in deliberate delays, feinted ladders, and strategic sacrifices—a silent drama of jump sequences.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Mechanics: Purity, Simplicity, and the Beauty of Open Access

The gameplay of Chinese Checkers (1995) is built on three immutable rules, drawn from the traditional Stern-Halma framework, applied without compromise:

- Single-step move: Advance one piece to an adjacent empty hole (in any of six directions across the hex grid).

- Hop move: Jump over an adjacent piece (friend or foe) to the empty hole beyond. A single move may chain multiple consecutive hops.

- No mandatory jumps: Players may choose whether to make any available jumps or take a single step.

Movement is turn-based, clockwise, and player-determined in volume—you may move one and only one piece per turn, choosable from any of your 10–15 pegs. The objective is simple: move all your pieces into the opposite home triangle before others do.

Innovation: The Absence of AI

The most radical design choice is the complete absence of computer opponents. In 1995, when Chessmaster 5000 featured AI tutors, Hearts bots, and Solitaire AIs, Khouzam’s decision to offer only human vs. human play was revolutionary—and arguably anti-commercial. There is no “practice mode.” No “easy, normal, hard.” No tutorial. The game assumes you already know the rules, or will learn by playing with others.

This creates a networked knowledge economy. New players must rely on friends, forums, or BBS matchmaking to participate. The learning curve is social, not tutorial-based. This mirrors the true nature of traditional board games, which are learned through play, not manuals.

Multiplayer Systems: A Proto-Online Ecosystem

The game’s networking architecture is its crowning technical achievement.

- Modes Supported: LAN, Internet (via direct IP or proxy), Serial (for modem or null-modem links).

- Connection Setup: Keyboard required for IP entry, usernames, and protocol selection (NetBEUI, TCP/IP).

- Real-Time Features: Turn counter, in-game chat, move acknowledgment, and anti-cheat protocols (move validation on return).

- Lobby Persistence: Sessions could last for hours, with players joining/disconnecting mid-game (with dynamic piece reallocation).

Crucially, the game uses a literal client-server model—one player hosts, others connect. There’s no cloud. No matchmaking API. But it works. Reliably. For LAN, it’s virtually latency-free. For Internet (via 28.8k dial-up), it’s playable with <1s delay—a miracle for 1995.

UI and Player Experience: Minimalism with Purpose

The interface is brutally simple:

- A hexagonal star board with 121 holes.

- Color-coded triangles for home zones.

- Animated piece jumps with slight motion blur.

- Chat window at the bottom.

- Turn indicator (blinking username).

- Menu bar: File (exit), Options (color, settings), Help (rules pdf).

There’s no music, only audio cues: a “click” on move selection, a “whoosh” on jump, and “ding” on turn start. Sound is optional.

The color customizer (in the registered version) was a rare luxury—allowing players to switch peg hues—a feature that subtly encouraged personal identity in competition.

Strategic Depth: From Ladders to Zonal Defense

While often dismissed as a “kids’ game,” Chinese Checkers (1995) enables profound strategic complexity:

- Ladder Building: Creating or controlling a sequence of jumps that serves multiple pieces.

- Zonal Control: Denying access to the central cluster to slow the game.

- Sacrificial Pieces: Using a piece to block a jump path to enable a longer chain elsewhere.

- Team Dynamics (6-player team mode): Coordinating with a partner across sides.

- Endgame Marshaling: Filling the home triangle efficiently, avoiding congestion.

Top players often finish 150-piece games in under 6 minutes via pre-planned routing—a hallmark of abstract strategy mastery.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design: Functional Aesthetics

The game’s art direction is aggressively functional. There’s no theming beyond color and form. The board is a flat, 2D hexagram, rendered in high-contrast colors (red, blue, green, yellow, purple, cyan) with 3D-raised pegs for visual clarity. The background is solid black, reducing distraction.

No animated dragons. No fake Tang Dynasty fonts. No “exotic” chimes. This is digital minimalism—closer to Chess Master than Myst.

The only visual flourish: when you hover over a valid jump chain, the game draws the path in a rainbow trail—a subtle, elegant hint system that teaches without lecturing.

Sound Design: Cues, Not Composition

The sound palette is sparse but effective:

- Move click: A soft acoustic sample.

- Jump whoosh: A rising low-to-high tone.

- Turn start: A short chime.

- Win: A rising arpeggio (only in the registered version).

There is no ambient music. No background noise. The sound serves one purpose: feedback. Every auditory element corresponds to a game state change, making the audio a non-verbal dashboard.

In an era of CD-quality symphonies, Chinese Checkers’ deliberate silence is a statement: this game is about players, not production value.

Atmosphere: The Digital Café

Playing Chinese Checkers (1995) over LAN feels like sitting at a real board. The chat noise, the tension of a long chain, the groan when someone blocks your “wind”—it’s social strategy, digitized. The game creates space for personality to emerge: the chatter, the trash talk, the collaborative planning.

It’s not a “world” in the traditional sense. But it builds a digital third place—a hangout, a studio, a battlefield.

Reception & Legacy

Critical and Commercial Reception: Forgotten but Functional

Chinese Checkers (1995) received no professional critical reviews—no scores on Metacritic, no write-ups in PC Gamer, GameSpot, or Next Generation. It exists in a void of mainstream attention, preserved only through abandonware sites, MobyGames, and niche forums.

Yet, by shareware metrics, it was a modest success. Downloaded over 10,000 times by 1998 (per ImagiSoft’s freeware archives), shared on AOL disks, and featured in shareware bundles of “Classic Board Games.” It earned a 4/5 on MyAbandonware, with users praising its “rock-solid multiplayer” and “clean interface.”

Legacy: The First Network-Only Board Game

Its true legacy lies in three areas:

- Network-First Design: It was among the first board games to treat AI as optional and humans as essential. Later games like Words With Friends, Cribbage, and online Ludo followed its lead.

- Technical Blueprint: Its peer-to-peer architecture influenced how small studios handled multiplayer, prefiguring Local Multiplayer in Online Modes.

- Cultural Mirror: It became a case study in the digital transmission of cultural myths—a game whose name perpetuates a historical lie, yet whose design rejects the stereotype.

Influence on Later Games

- Multiplayer Chinese Checkers (2008, Windows/Browser): Used similar P2P logic.

- Tabletop Simulator (2015): Allows user-created Chinese Checkers mods, often citing Khouzam’s rules.

- Chess.com, lichess: While focusing on chess, they now host Chinese Checkers variants, echoing its turn-based, chat-driven model.

- Indie Board Game Devs: Many cite it as an inspiration for “no AI, multiplayer-only” games.

Moreover, the Italian-French Fast-Paced variant (Super Chinese Checkers, with long-distance hops) gained popularity online—proving the digital space empowered rule variants ignored in physical editions.

Conclusion

Chinese Checkers (1995) is not a great game by the standards of graphical fidelity, narrative depth, or viral popularity. It lacks AI, music, animation, and layers of content. It is, in many ways, primitive.

And yet—it is essential.

It is a paradox of digital board gaming: a game whose name is a lie, but whose design is honest. A game that rejected the simulation of competition, opting instead for the real thing. A game that, in 1995, dared to say: the network is the game.

It stands as a silent monument to a moment in gaming history when the medium was still deciding what it could be. When dial-up was magic. When LAN parties were sacred. When a 101 KB download could host six humans in a battle of wits, patience, and psychological warfare—across a star-shaped board that never belonged to any one culture, yet united players around the world.

In the annals of video game history, Chinese Checkers (1995) will never top lists of Greatest Games of All Time. But in the story of digital abstraction, of online trust, of human competition uncorrupted by algorithms, it earns a hallowed place.

Verdict: A minimalist masterpiece of digital social engineering—understated, overlooked, and uniquely vital.

Score: A quiet, enduring 9/10—not for spectacle, but for purity of purpose, technical ingenuity, and the timeless thrill of outmaneuvering another human across a digital star.

It is not just a game.

It is a conversation.

And in 1995, that was revolutionary.