- Release Year: 1989

- Platforms: Lynx, DOS, Amiga, Atari ST, Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum, Amstrad CPC, Windows 16-bit, Windows, Antstream, SNES, Genesis, Nintendo Switch

- Publisher: Atari Corporation, U.S. Gold Ltd., Epyx, Inc., Microsoft Corporation, Nkidu Games Inc., Niffler Ltd., The Retro Room Games LLC, Pixel Games UK

- Developer: Epyx, Inc.

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: Top-down

- Gameplay: Puzzle

- Setting: Puzzle

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

Nerdy Chip desperately wants to join the exclusive ‘Bit Busters’ computer club, led by Melinda the Mental Marvel, but must first pass a rigorous initiation test. This entails navigating 149 increasingly difficult, tile-based puzzle levels where he must utilize tools like keys and special shoes, manipulate switches, and build bridges across waterways. The goal in each level is to avoid enemy creatures, collect all the scattered computer chips, and reach the exit before a challenging time limit runs out.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Get Chip’s Challenge

Atari ST

Commodore 64

DOS

Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org : Chip’s Challenge is a top-down tile-based puzzle video game originally published in 1989.

godmindedgaming.com : I’d suggest giving it a go if you want to experience some 1990s-era charm, but I think most of today’s kids will find it frustrating or boring rather quickly.

forums.overclockers.com.au : Retro Let’s Play: Chip’s Challenge (1989)

imdb.com (80/100): Excellent for everyone patient, good for everyone else.

gamespot.com (80/100): While some may find the game repetitive, its complex puzzles and the elegant solutions needed to solve them are very appealing.

Chip’s Challenge: A Masterclass in Enduring Puzzle Design

In the vast annals of video game history, there are titles that emerge not through groundbreaking technology or sprawling narratives, but through the sheer brilliance of their core mechanics and level design. Chip’s Challenge is one such enigma – a seemingly simple top-down puzzler that, born on an early handheld and later adopted by the ubiquitous PC, cemented itself as a timeless test of wit and will. Decades after its initial release, its influence resonates, a testament to the ingenious mind of its creator and the dedicated community it fostered. This review delves deep into the layers of this iconic game, exploring its origins, intricate gameplay, and indelible mark on the industry.

Development History & Context

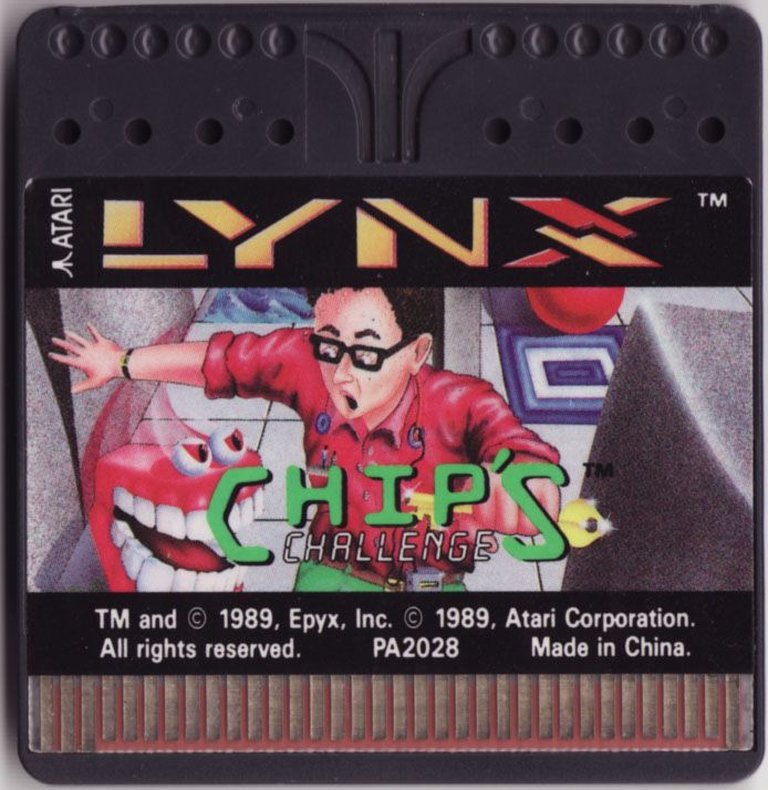

Chip’s Challenge first graced screens in 1989, a launch title for the Atari Lynx, a handheld console aiming to challenge the burgeoning dominance of Nintendo’s Game Boy. The game was the brainchild of Chuck Sommerville, who led a team at Epyx, Inc. His vision, initially prototyped on an Apple II to demonstrate its core fun factor, focused on creating a compelling puzzle experience. Sommerville personally designed approximately a third of the game’s initial levels, with another third crafted by professional puzzle designer Bill Darrah, and the remainder by Epyx’s team of programmers and playtesters, including James Donald, Peter Engelbrite, and Victoria Hanson.

The gaming landscape of 1989 was ripe for innovation in the puzzle genre. Games like Sokoban and Boulder Dash had already laid groundwork for tile-based, block-pushing challenges. Chip’s Challenge entered this arena, building upon these established concepts while introducing its own unique blend of elements. The Atari Lynx platform, while advanced for its time with a color screen, imposed certain technological constraints. The game’s 32×32 tile board and a camera that typically only showed a few squares ahead necessitated a design philosophy that maximized challenge within confined visual space.

Its true ascent to widespread recognition, however, came years later. In 1992, Microsoft licensed Chip’s Challenge from Epyx, including it in the highly successful Microsoft Entertainment Pack 4 for Windows 3.1, and later in the Best of Microsoft Entertainment Pack (1995). This PC version, developed by Microsoft under Tony Garcia, coded by Tony Krueger, and with art by Ed Halley, became the most familiar iteration for a generation of players. While this port featured “significantly different sound and graphics” and was noted to have been “coded in a single summer,” it exposed Chip’s Challenge to a massive audience, transforming it from a niche handheld gem into a cult classic and an early example of casual gaming’s potential.

Beyond its Lynx debut, the game saw numerous conversions by Images Software in the UK to other platforms in the early 1990s, including DOS, Amiga, Atari ST, Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum, and Amstrad CPC. Decades later, its enduring appeal led to further re-releases on modern platforms like Steam (2015), Antstream (2019), SNES/Genesis (2021), and even Nintendo Switch (2024), proving its foundational design transcended its original hardware.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its heart, Chip’s Challenge presents an “excuse plot” that, while minimalist, sets a charmingly relatable stage for its intricate puzzles. The protagonist is Chip McCallahan, a “nerdy” high-schooler whose eyes meet those of Melinda the Mental Marvel in the school science laboratory – “the chemistry was instantaneous!” Chip’s ultimate goal is to prove his intelligence and secure membership to Melinda’s exclusive “Bit Busters” computer club. To achieve this, he must navigate Melinda’s “Clubhouse,” a labyrinthine series of increasingly difficult puzzles, collecting “cosmic computer chips” along the way.

Characters:

- Chip McCallahan: Our eponymous hero, Chip embodies the “dogged nice guy” trope. He is a “one-hit-point wonder,” vulnerable to every hazard, yet persistent. His signature sound effect, a disheartened “Bummer!” upon death, became an iconic piece of game lore, perfectly encapsulating the blend of frustration and charm that defines the game. His transformation in the victory screen of the Windows version, from a simplified sprite to a red-haired, glasses-wearing figure cheered by a crowd, underscores his journey from underdog to respected “puzzle master.”

- Melinda the Mental Marvel: The object of Chip’s aspirations and the gatekeeper to the Bit Busters Club. Melinda is portrayed as a “teen genius,” reportedly “preoccupied in the upper levels, creating mental models to test Hawking equations on the origin of the universe.” Her role extends beyond a narrative device; she provides helpful hints via yellow tiles and, notably, offers a “Mercy Mode” allowing players to skip levels if they demonstrate enough “perseverance” (defined as at least 10 deaths in a row where Chip was alive for 10 seconds). She serves as both motivator and implicit guide.

Dialogue & Themes:

Dialogue is sparse, limited primarily to level hints and Chip’s death vocalizations. The narrative’s simplicity is a deliberate choice, prioritizing gameplay over exposition. Yet, within this minimalist framework, several themes emerge.

- Perseverance and Intelligence: The core challenge revolves around proving Chip’s intelligence. This directly translates to the player’s experience, demanding logical thinking, pattern recognition, and relentless trial-and-error. The game doesn’t just ask players to complete levels; it asks them to learn and adapt.

- Deceptive Simplicity: A recurring theme is that the game, with its seemingly basic graphics and controls, hides immense depth and complexity. As one critic noted, “creativity is making the most out of what little there is.” This forces players to look beyond superficial elements and engage deeply with the puzzle logic.

- The “Nerd Makes Good” Trope: Chip’s journey from a “nerdy” outsider to a club member, if not a “puzzle master” in the sequel’s language, taps into a classic narrative archetype. It resonates with players who appreciate intellectual challenge over brute force.

- Bowdlerization and Canon: An interesting narrative nuance involves the “Bowdlerization” between the Lynx and Microsoft versions. The Lynx version hinted at Chip’s motivation being a desire to take Melinda to the prom, with magazine ads even implying romantic subtext (“is Chip man enough to get into Melinda’s club?”). The Microsoft version, however, toned this down, focusing solely on Chip’s genuine interest in joining the Bit Busters club. Chip’s Challenge 2 later reverted to the Lynx canon, suggesting the original, slightly more romantic undertone held more sway with the creator.

Ultimately, the “Clubhouse” itself functions as the primary “character,” a mysterious world filled with “magic, mystery, and danger.” The levels, with their often punny or descriptive titles (“Southpole,” “Nice Day,” “Cake Walk”), imbue personality and subtle clues, deepening the player’s engagement with the abstract puzzle environment.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Chip’s Challenge is a masterful example of elegant design, where a relatively small set of interacting elements generates an astonishing variety of complex puzzles. At its core, it’s a top-down, tile-based puzzle game with a straightforward objective: guide Chip McCallahan through each level, collect all the required computer chips, and reach the exit (the “chip socket”) before a time limit expires.

Core Gameplay Loop:

Players use arrow keys or a numeric keypad for precise direct control over Chip’s movement. While the Windows version introduced mouse support, it came with noted limitations: commands didn’t account for hazards, Chip would bump into walls if more than two directions were involved, and it wouldn’t cancel keyboard commands, making precision more difficult. This highlights the game’s emphasis on careful, deliberate movement. The experience is strictly single-player.

Obstacles & Tools: A Symphony of Interaction

The genius of Chip’s Challenge lies in its diverse array of tiles and objects, each with unique properties that combine to create intricate challenges:

-

Lethal Hazards:

- Water: Instantly drowns Chip unless he has swim fins.

- Fire: Burns Chip (leaving an “ash face” sprite in the original Windows version) without fire boots.

- Monsters: Nine distinct types of creatures, each with unique movement patterns. Examples include:

- Yellow Bugs: Patrol walled areas counterclockwise.

- Blue/Red Teeth: Blue teeth run away from Chip, red teeth chase him (Melinda in CC2 reverses this).

- Pink Balls: Bounce unpredictably.

- Gliders: Can hover over water.

- Blobs: Move randomly, infamously tricky in levels like “Blobnet.”

- Walkers: Can be manipulated by blocks or sand.

- All monsters inflict collision damage, resulting in Chip’s “Bummer!” death.

- Bombs: Red, round “Cartoon Bombs” instantly kill on contact but can be detonated by pushing blocks or luring monsters onto them.

- Force Floors (Conveyor Belts): Propel Chip in specific directions, often into hazards, unless he has suction-cup shoes.

- Ice: “Frictionless Ice” causes Chip (and monsters/blocks) to slide at double speed, bouncing off walls until hitting a floor tile. Ice skates negate this.

- Thieves/Spy Panels: Steal Chip’s footwear and equipment (or keys in CC2) upon contact.

- Gender-Restricted Walls: Female/male restroom signs Chip/Melinda cannot pass, adding thematic barriers.

-

Manipulable Elements & Keys:

- Color-Coded Keys & Doors: Red, blue, yellow, and green keys correspond to specific doors. Keys vanish upon use (except green keys, and yellow keys for Melinda in CC2), creating classic Lock and Key Puzzles where resource management is crucial. Levels like “Trust Me” and “Goldkey” are famous for their intricate key-management challenges.

- Pushable Blocks: Essential for building bridges over water, triggering pressure plates, or blocking monsters. Blocks cannot be pulled, and sliding blocks can crush Chip.

- Dirt Blocks: Can be dug through, used to manipulate monster paths, or reveal hidden items/traps.

- Switches/Buttons:

- Brown Pressure Plates: Must be continuously pressed by Chip or a block to disable traps.

- Green Toggle Buttons: Globally switch the state of “Toggle Walls” (from impassable to passable and vice-versa), often requiring careful timing or monster manipulation.

- Blue Buttons: Control “Blue Tanks,” turning them around to move in the opposite direction.

- Red Buttons: Activate “Mook Makers” (Clone Machines) to spawn monsters or blocks, a versatile puzzle mechanic.

- Invisible Walls: Some appear permanently after bumping, others are temporary, forcing exploration and memory.

- Hint Tiles: Yellow question mark tiles provide advice or teach game elements, especially in the early “Lesson” levels.

Level Design & Progression:

The game features 149 levels (148 in the Lynx version, with an extra “Thanks to…” level 145/149 in the Windows version), designed with a “sanft, aber stetig ansteigende Schwierigkeitsgrad” (gently but steadily increasing difficulty). The first eight levels are explicit tutorials. The variety is immense, ranging from:

* Mazes: Levels like “Southpole” (ice maze), “Cellblocked” (recessed walls preventing backtrack), “Mishmesh” (blue walls), “Rink” (ice maze), “Stripes?” (partly invisible walls), and “Doublemaze.”

* Block Puzzles: Many levels adopt a Sokoban-style approach, requiring precise block manipulation (e.g., “Castle Moat,” “On the Rocks,” “Cityblock,” “Pain,” “Writer’s Block” – notorious for their length and complexity).

* Monster Manipulation: Directing enemies to hit buttons or clear paths (e.g., “Metastable to Chaos,” “Lemmings,” “Traffic Cop”).

* Timed Action: Levels requiring quick reflexes and pattern memorization (“Ping Pong,” “Bounce City”).

* Pixel Hunts/Trial-and-Error: Levels with fake or invisible walls, or items hidden under blocks (“Mishmesh,” “Scoundrel,” “Special” – the final secret level, where most blocks hide fire).

* Control Room Puzzles: Multi-layered challenges involving various button interactions (e.g., “Monster Lab,” “Perfect Match”).

Anti-Frustration Features & Notable Flaws:

* Passwords: Four-letter passwords allow players to return to specific levels, mitigating the lack of in-level saving. Level 34 (“Cypher”) cleverly incorporates password deciphering.

* Mercy Mode: After multiple failures (usually 10 deaths after 30 seconds of play), Melinda offers to let Chip skip a level, a benevolent anti-frustration feature.

* Unwinnable by Design: A significant challenge and source of frustration. Many levels become unsolvable with a single misstep, forcing a restart (“Cellblocked”).

* Microsoft Version Glitches: The Windows port notoriously introduced bugs that impacted gameplay, sometimes simplifying levels (e.g., bypassing force floors with ice boosts, clone machines failing) or making others excruciatingly difficult (e.g., “block slapping” technique on Lynx, where blocks could be moved from the side without risk of fire underneath, was removed, making “Special” a luck-based challenge). A Game-Breaking Bug could crash the game if three or more entities occupied a single tile.

Replayability:

Beyond completing all 149 levels, the game offers substantial replay value. Players can aim for high scores (based on time and attempts), engage in speedrunning (an early community formed around this), or explore the vast landscape of community-made levels through level editors and fan sequels (like the Chip’s Challenge Level Packs).

World-Building, Art & Sound

The “world” of Chip’s Challenge is less a fully realized environment and more a conceptual space: Melinda’s “magical clubhouse.” It’s an abstract setting designed purely to facilitate the intricate puzzle mechanics. The visual and auditory elements, while functional, generally take a back seat to the gameplay, an intentional choice given the technological limitations of the era.

Visual Direction:

The game employs a top-down, tile-based perspective with simple, “iconic graphics.” Reviewers at the time often described the visuals as “dull looking” (Retro Gamer), “laughably simplistic” (CVG), or “altbacken” (old-fashioned, PC Joker). However, most acknowledged that these “functional” graphics served their purpose, allowing the player to clearly distinguish different tile types and interactive elements. The original Lynx version, with its limited color palette, informed the look. The Windows 16-bit version, while offering “enhanced graphics” (as featured in Microsoft Entertainment Pack 4), maintained the pixelated, sprite-based aesthetic. The Windows version also included a Colorblind Mode, providing unique patterns to keys, doors, and buttons instead of relying solely on color. Subtle differences, like Chip’s icon having “different coloring” or the presence/absence of an “ash face” sprite after stepping on fire, varied between ports. Ultimately, the visual design is a masterclass in “creativity is making the most out of what little there is,” prioritizing clarity and gameplay over graphical extravagance.

Sound Design:

Much like the visuals, the sound design is often described as utilitarian. Critics noted the “monotonous tunes” (Retro Gamer) and “inoffensive if endlessly repetitive” musical accompaniment (The One). Some, like CVG, found the music an “annoyingly jolly tune.” Credits for sound and music go to Alex Rudis and Robert Vieira for the Lynx version, with David Whittaker credited in some player reviews for the Amiga version. A player review of the Atari ST port noted that the music suffered from “lesser fidelity” and could “drown out the sound effects.”

However, one element of the sound design achieved legendary status: Chip’s “Bummer!” exclamation upon death. This signature sound effect became synonymous with the game, perfectly encapsulating the player’s frequent failures and the game’s challenging nature. The repetitive “Ugh” sound Chip makes while moving could also be toggled off, acknowledging player preference.

Contribution to the Overall Experience:

The minimalist art and sound contribute to the overall experience by stripping away distractions and forcing the player to focus intensely on the puzzle logic. The simple, clean visual language ensures that every tile’s function is immediately understandable, crucial for a game where a single misstep means restarting a level. The repetitive music, rather than being a flaw, often fades into the background, allowing the mental process of problem-solving to take center stage. The “Bummer!” sound, however, is a constant, albeit mild, reminder of the game’s unforgiving nature and the player’s journey through trial and error.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its release in 1989, Chip’s Challenge garnered significant critical acclaim, particularly for its Lynx debut. With an average critic score of 78% and a Moby Score of 7.2, it quickly established itself as a standout puzzle title. Reviewers consistently lauded its “addictive punch,” “ingenious obstacles,” and “huge amount of fiendish imagination.” The Atari Times gave the Lynx version 90%, calling it “one of the Lynx’s true gems” with a “perfect learning curve” for all ages. Power Play declared it the “Best Lynx Game in 1990,” and Commodore Format later enshrined it in its “all time Top Ten Essential Mega Games” in 1992.

While critics often noted the “dull looking visuals and monotonous tunes” (Retro Gamer) or “average graphics and sound” (CVG), they universally agreed that these aesthetic shortcomings were irrelevant in the face of its exceptional gameplay. As The One succinctly put it, “in this game, frills don’t count… What you have is a puzzle player’s dream.” The sheer volume of levels (149) and their escalating, well-designed difficulty were frequently highlighted, promising “wochenlanges Tüftelvergnügen” (weeks of tinkering pleasure) and making it “incredibly addictive” and “extremely difficult to put down” (ST Format). The constant frustration of repetition was acknowledged, but largely overshadowed by the satisfying “Aha!” moments of solving a particularly devious puzzle.

Commercial Success and Evolving Reputation:

The game’s commercial success exploded with its inclusion in the Microsoft Entertainment Pack 4 for Windows. This exposure transformed it into a “cult classic,” reaching a far wider audience than its original handheld or home computer ports. Over the decades, Chip’s Challenge has maintained a fervent fanbase. It’s often referred to as a “Criterion ass videogame,” recognized by developers and historians for its fundamental design principles, even if the general public (under 45) might not explicitly name it. It also fostered one of the earliest speedrunning communities, with players racing to achieve world records, a tradition that continues to this day.

Influence on Subsequent Games & The Industry:

The legacy of Chip’s Challenge extends far beyond its initial run. It became a foundational title in the puzzle genre, deeply influencing subsequent game design:

- Modding and Community Content: The game was a pioneering example of community-driven content. Early BBS and internet forums saw users sharing homemade level editors and unofficial expansion packs, predating widespread modding culture. This led to the creation of thousands of fan-made levels, with the most well-received compiled into “Fan Sequels” known as the Chip’s Challenge Level Packs (CCLP1-5).

- Official Sequels and Successors: Chuck Sommerville himself recognized the game’s enduring appeal. He created Chip’s Challenge 2 in 1999, though it languished in “copyright limbo” for 15 years due to legal issues with Bridgestone Multimedia Group, who acquired Epyx’s assets. It was finally released on Steam in 2015, alongside an updated re-release of the original, utilizing the sequel’s engine. During this limbo, Sommerville also developed creator-driven successors like Chuck’s Challenge (2012, iOS) and Chuck’s Challenge 3D (2014, PC/Mac/Android/iOS), further iterating on the core mechanics. It even served as the basis for official Ben 10 games, showcasing its versatility.

- Genre Archetype: Its blend of environmental puzzles, timed challenges, monster avoidance, and resource management became an archetype. While hyperbole, claims that games like Pokémon (for its tile-based navigation), Dr. Mario World, Tile World, or even Wolfenstein and DOOM “rip pages right out of the book of Chip” speak to its fundamental impact on how developers think about level design and player interaction in grid-based environments.

- Enduring Relevance: The ongoing re-releases on platforms like Steam and Nintendo Switch, often with modernized features but retaining the core gameplay, confirm its status as an enduring classic. Its ability to transcend generations and platforms is a testament to the purity and robustness of its design.

Conclusion

Chip’s Challenge is more than just a video game; it’s a testament to the power of pure, unadulterated gameplay. Born on the Atari Lynx and later finding its true audience through the Windows Entertainment Packs, it carved out an essential niche in the history of puzzle games. Its narrative, while charmingly minimalist, perfectly frames the intellectual quest it demands of players, a journey of perseverance and cleverness led by Chip McCallahan’s endearing “Bummer!”-laden failures.

The brilliance of Chip’s Challenge lies in its meticulously crafted gameplay loop: a deceptive simplicity masking profound depth. Chuck Sommerville and his team masterfully balanced a limited palette of obstacles and tools—keys, shoes, blocks, monsters, and environmental hazards—to create 149 levels of ever-escalating ingenuity. Despite technological constraints that necessitated basic graphics and sound, the game’s functional aesthetics became part of its identity, pushing players to focus entirely on the intricate logic of each puzzle. The inclusion of anti-frustration features like passwords and Melinda’s mercy option, alongside the unforgiving trial-and-error nature of its unwinnable levels, created a unique blend of challenge and accessibility that hooked millions.

Its legacy is undeniable. Chip’s Challenge not only became a critical and commercial success but also ignited an early, vibrant modding community, inspiring countless fan-made levels and directly influencing official sequels and spiritual successors. It proved that exceptional puzzle design transcends technological limitations, securing its place not just as a beloved retro title, but as a foundational blueprint for tile-based logic games. Chip’s Challenge remains a timeless classic, a definitive verdict on the enduring appeal of clever design and the satisfying triumph of intellect over adversity.