- Release Year: 1980

- Platforms: Antstream, Atari 2600, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Atari Corporation, Microsoft Corporation, Sears, Roebuck and Co., Zellers

- Developer: Atari Corporation

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Hotseat

- Gameplay: Arcade

- Setting: Circus

- Average Score: 90/100

Description

Circus Atari is a classic arcade-style action game set in a whimsical circus environment, where players control a teeter-totter to catch falling clowns and bounce them upward to pop a colorful wall of red, blue, and white balloons at the top of the screen, earning points with each successful pop. Released in 1980 for the Atari 2600, the game features simple yet addictive paddle-controlled gameplay for one or two players, with increasing speed and difficulty as balloons regenerate, and a comedic twist where missed catches result in clowns comically crashing to the ground, limiting each player to five turns before the game ends.

Gameplay Videos

Circus Atari Free Download

Atari 2600

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

atariarchive.org : It’s a clever game that is more interesting than Breakout.

atarihq.com (90/100): Nevertheless, Circus Atari is a favorite of mine, and is a refreshing change from Breakout.

honestgamers.com : Ahhh Circus Atari, one of my absolute favorite Atari 2600 games.

Circus Atari: Review

Introduction

Imagine a pair of frantic, stick-figure clowns hurtling through the air, arms flailing wildly as they smash into floating balloons, all while a jaunty tune plays in the background—welcome to the chaotic charm of Circus Atari, a 1980 Atari 2600 gem that turned arcade whimsy into home console magic. As one of the earliest ports of Exidy’s 1977 arcade hit Circus, this game arrived at a pivotal moment in video gaming history, bridging the gap between coin-operated spectacles and the living room. Its legacy endures not just as a nostalgic nod to paddle-controlled classics but as a testament to how simple ideas could spark joy, addiction, and even cultural ripples, like inspiring Japan’s Yellow Magic Orchestra to sample its sounds for pioneering electronic music. In this review, I argue that Circus Atari is a masterful evolution of the Breakout formula, blending humor, precision control, and replayability into a title that punches above its 2KB weight class, cementing its status as an essential Atari 2600 artifact that reveals the era’s boundless creativity.

Development History & Context

The story of Circus Atari is one of arcade-to-home adaptation amid the explosive growth of the video game industry in the late 1970s. Developed by Atari, Inc.—the undisputed titan of early console gaming—the title was programmed primarily by Mike Lorenzen, a talented engineer whose work on this and contemporaries like Golf showcased Atari’s ability to squeeze innovative gameplay from the Atari 2600’s limited hardware. Lorenzen’s involvement was serendipitous and fraught with drama: the project began under an unnamed developer who struggled for months, leaving behind cryptic code saved on locked floppy disks. When marketing prematurely promised the game in catalogs, Atari roped in Lorenzen to salvage it covertly. He decoded the mess, fixed bugs, and completed it in record time, earning a $7,000 bonus for his efforts. This behind-the-scenes intrigue highlights Atari’s high-stakes environment, where rapid iteration was key to staying ahead of rivals like Activision and Imagic.

The original Circus arcade game, released by Exidy in December 1977, was the brainchild of co-founders Howell Ivy and Edward Valeau, building on Ivy’s earlier work at Ramtek on Clean Sweep—a precursor to Breakout. Exidy, founded in 1973 amid the Pong boom, had tasted controversy with Death Race (1976) but shifted to microprocessor-driven titles for flexibility. Ivy coded Circus on a 6502 processor using a teletype, adding color via cellophane overlays on the cabinet’s screen—a clever hack to make balloons pop with visual flair. The vision was “cute” and non-violent, targeting female players with its fluffy, clown-themed antics, contrasting the era’s aggressive shooters. Exidy reused hardware from Car Polo to cut costs, allowing dynamic elements like flailing clowns and generated music—innovations billed as arcade firsts.

Technological constraints defined the port: the Atari 2600’s 128 bytes of RAM and 4KB addressable ROM demanded ruthless optimization, resulting in a mere 2KB cartridge. Paddle controllers were mandatory for precise seesaw control, a nod to arcade joysticks but a limitation for joystick users. Released on January 10, 1980 (per U.S. Copyright Office records), it hit shelves during the 2600’s golden age, post-Space Invaders frenzy but pre-crash saturation. The gaming landscape was arcade-dominated, with home systems like the 2600 selling via ports of hits like Asteroids. Circus Atari filled a niche for family-friendly action, distributed by Atari and variants like Sears’ Tele-Games edition, amid competition from Breakout clones. This context underscores Atari’s strategy: democratize arcade fun while innovating on hardware limits, paving the way for the console’s 30-million-unit legacy.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Circus Atari eschews traditional storytelling for pure, comedic spectacle, embodying the era’s “no plot, no problem” ethos where gameplay is the narrative. There’s no overarching plot—just an endless circus performance where two nameless clowns (depicted as lively stick figures) perpetually bounce toward glory or comedic disaster. The “plot,” if it can be called that, unfolds in vignettes: a clown launches from a trampoline, lands on the seesaw, propels his partner skyward to burst balloons, and the cycle repeats until a splat-ending mishap. Pressing the paddle button summons the next jumper, creating a rhythmic loop of anticipation and payoff, like a never-ending vaudeville act.

Characters are archetypal and endearing: the clowns, with their exaggerated flailing limbs, evoke non-ironic harlequins—clumsy yet determined performers in a big-top world. No dialogue exists, but the game’s “narrative” speaks through actions and sounds: triumphant boings for successful pops, a mournful funeral march snippet from Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2 for crashes (a public domain touch adding ironic pathos). Themes revolve around comedy and resilience; the clowns’ persistent returns after “deaths” mirror the arcade’s hot-seat multiplayer, symbolizing the joy of failure in gaming’s early days. Underlying motifs include physics-defying spectacle—balloons as fragile dreams, the seesaw as a fulcrum of fate—and a lighthearted critique of performance pressure, with clowns comically deflating egos (literally).

In extreme detail, the thematic depth emerges in failure states: a missed catch results in a head-first splat, legs kicking futilely half-buried in the ground—a slapstick homage to Looney Tunes physics that humanizes the abstract. Success yields bonuses, like extra lives for clearing the top row, reinforcing themes of perseverance. As a comedy narrative, it draws from circus lore (clowns, acrobats) to subvert Breakout‘s sterility, injecting warmth and whimsy. This thematic simplicity belies profound engagement: players project their own stories onto the chaos, turning abstract popping into a personal high-score saga. Compared to narrative-heavy contemporaries like Adventure, Circus Atari proves thematic purity can be as compelling as epic quests, especially in an era when games were diversions, not novels.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Circus Atari is an arcade-style block-breaker deconstructed through physics-based clown-bouncing, creating a loop of precision, timing, and escalating chaos. Players control a seesaw via paddle for fluid horizontal movement, starting with one clown perched on one end. Pressing the button launches a second from a side trampoline; catch him on the empty end to catapult the first upward at variable angles based on landing position—edge hits yield steeper trajectories for reaching high balloons. The airborne clown flails into three scrolling rows of colored balloons (yellow bottom: 20 points; green middle: 50; red top: 100), popping them on contact. Bouncing varies by mode: “Breakout Circus” (Game 1) has realistic ricochets off balloons and walls; “Breakthru Circus” (Game 3) lets clowns pierce vertically for multi-pops. Catch the returning clown to continue, or he splats, costing a life (five total, plus bonuses).

Progression is score-driven and endless, with speed ramping after row clears—balloons regenerate immediately in standard modes, but “Circus Challenge” (Game 5) requires full clearance for respawns, heightening tension. UI is minimalist: score, lives (X icons), and game select on boot; no pause, but difficulty switches alter bounce speed (A for frantic, B for forgiving). Multiplayer is hot-seat, alternating turns or sharing fields (Game 7/8), fostering competition without split-screen.

Innovations shine in adaptations: the seesaw-flip button compensates for absent arcade side platforms, enabling quick pivots; barriers in variants (Games 2/4/6/8) add obstacle navigation, forcing angled shots and rewarding ricochet chains. Flaws include inconsistent height mechanics—clowns sometimes undershoot despite perfect catches, frustrating precision—and rightward action bias, as noted by critics. No combat exists, but “fights” with physics feel tactical, like angling for bonus rows (10x points, extra life for top row). Variants provide replayability: eight total, from basic to barrier-scrolling marathons. The loop—launch, catch, pop, repeat—hooks via risk-reward, with splats adding humorous punctuation. Overall, it’s a refined Breakout system, innovative in personality but flawed by hardware limits, demanding mastery for high scores.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Circus Atari‘s world is a vibrant, abstracted big top: a blue void sky evokes an endless circus tent, with side trampolines as entry points and the seesaw as the central stage. Balloons scroll horizontally like drifting performers, barriers (in variants) as pesky rigging—minimalist world-building that prioritizes function over lore, yet builds an atmospheric playground of perpetual motion. The setting fosters immersion through rhythm: balloons’ parade-like flow creates urgency, while the ground’s implied hardness amplifies splat comedy, turning the screen into a stage of triumph and tumble.

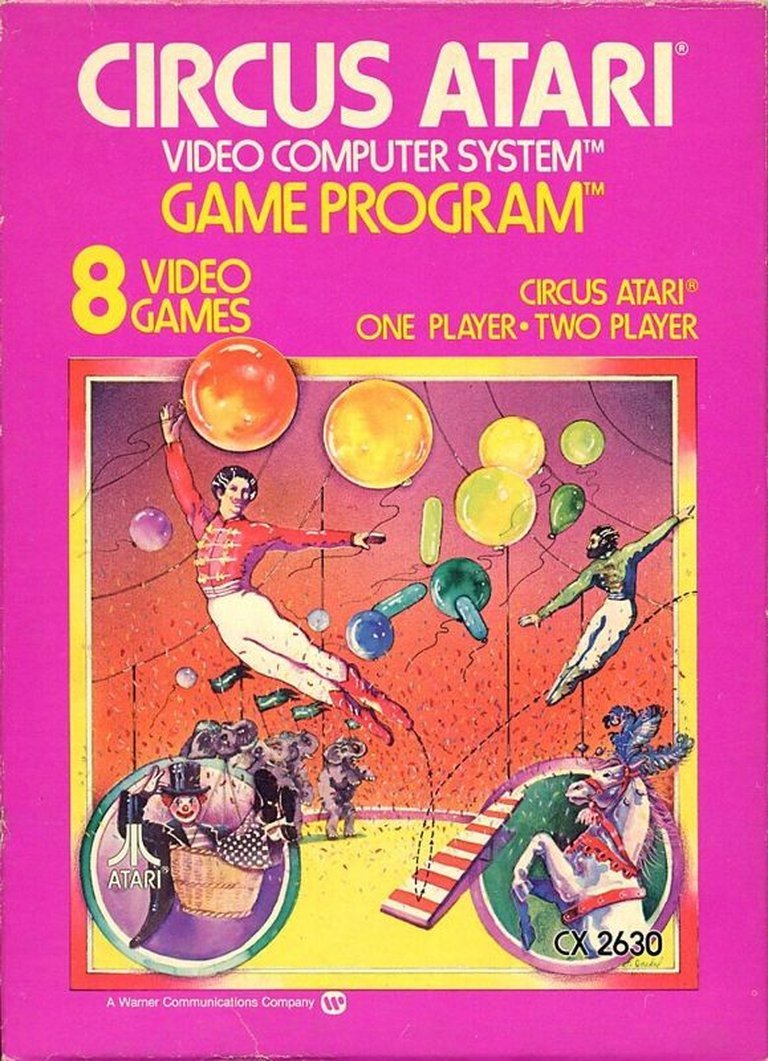

Visual direction is era-defining Atari charm—blocky yet expressive. Clowns are stick-figure icons with animating limbs for personality, their flails conveying panic or glee; balloons are square but color-coded for clarity (red top, green middle, yellow bottom). The 2600’s 128-color palette shines in B&W or color modes, with paddle-synced smoothness preventing flicker. Art contributes to experience by emphasizing chaos: rapid pops create satisfying cascades, while barriers add spatial depth without overwhelming the 160×192 resolution. Cover art by Susan Jaekel depicts whimsical clowns mid-leap, capturing the game’s lighthearted vibe.

Sound design amplifies the circus motif with primitive beeps: boings for bounces, sharp pops for balloons, and a descending whine for splats—iconic and replayable. The funeral march on failures adds thematic irony, while bonus chimes (Tarara-Boom-De-Ay tune) evoke celebration. No voice or complex score, but the generated effects—pioneered in the arcade—feel alive, syncing with visuals for tension release. These elements coalesce into an atmospheric whole: visuals provide clarity and humor, sounds punctuate rhythm, transforming a sparse world into an addictive, joyful spectacle that lingers like a carnival echo.

Reception & Legacy

Upon 1980 release, Circus Atari garnered solid acclaim as a paddle essential, with MobyGames aggregating 78% from six critics—praise for its addictive simplicity amid the 2600’s 100+ library. Atari HQ (9/10) hailed it as a “refreshing change from Breakout,” lauding humor and control; JoyStik (7.3/10) called it “basically the same as Breakout—only better.” Woodgrain Wonderland gave 100/100 for its “blast to play” dynamics, while Video Game Critic (67/100) noted frantic fun despite action bias. Players averaged 2.9/5 (MobyGames), with gametrader praising pick-up-and-play charm but critiquing its dated feel post-Space Invaders. Commercially, it sold modestly—148,756 first-year units (per internal docs), totaling ~2.7 million lifetime per Lorenzen—trailing blockbusters but boosted by bundles and ads.

Reputation evolved positively in retro circles: Creative Computing (1981) deemed it family-friendly; HonestGamers (2003) called it a “must-have” for laughs and addiction. The 1983 crash dimmed visibility, but re-releases in Atari: 80 Classic Games in One! (2003), Atari Vault (2016), and Atari 50 (2022) revived it, alongside Xbox 360/Windows (2010) and Antstream (2021). Legacy extends beyond sales: the arcade original’s sounds influenced YMO’s Yellow Magic Orchestra (1978), sparking video game music (e.g., Hosono’s Video Game Music, 1984). Clones proliferated—Clowns (Midway), Acrobat (Taito, Japan’s 1978 top-earner), home ports like P.T. Barnum’s Acrobats! (Odyssey2, 1982) with voice synthesis, and open-source Circus Linux. It influenced block-breakers (Plump Pop, 1987) and homebrews like Super Circus Atari Age (Atari 7800). Industry-wide, it exemplified accessible ports driving console adoption, paving for paddle innovations in Arkanoid and modern endless runners—proving cute mechanics could outlast violence.

Conclusion

Circus Atari distills early gaming’s essence: innovative mechanics from humble origins, comedic flair masking depth, and enduring appeal in simplicity. From turbulent development to arcade roots, its Breakout twist via clowns and balloons crafts a world of rhythmic destruction that’s equal parts frustrating and hilarious. Gameplay loops reward precision amid chaos, visuals and sounds build whimsical atmosphere, and variants ensure longevity, while reception affirms its paddle prowess. Though flawed by tech limits, its influence—from music pioneers to clone waves—secures its place in history as a bridge between arcade novelty and home staple. Verdict: An unmissable 9/10 classic, essential for Atari enthusiasts and a reminder that sometimes, the best games are just clowns popping balloons—endlessly.