- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: GameStorm, Microforum Italia S.p.A., Monolith Productions, Inc., Russobit-M, Takarajimasha, Inc., Techland Sp. z o.o.

- Developer: Monolith Productions, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Online Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Boss battles, Collectibles, Combat, Platform, Puzzles

- Setting: Fantasy, Pirate

- Average Score: 94/100

Description

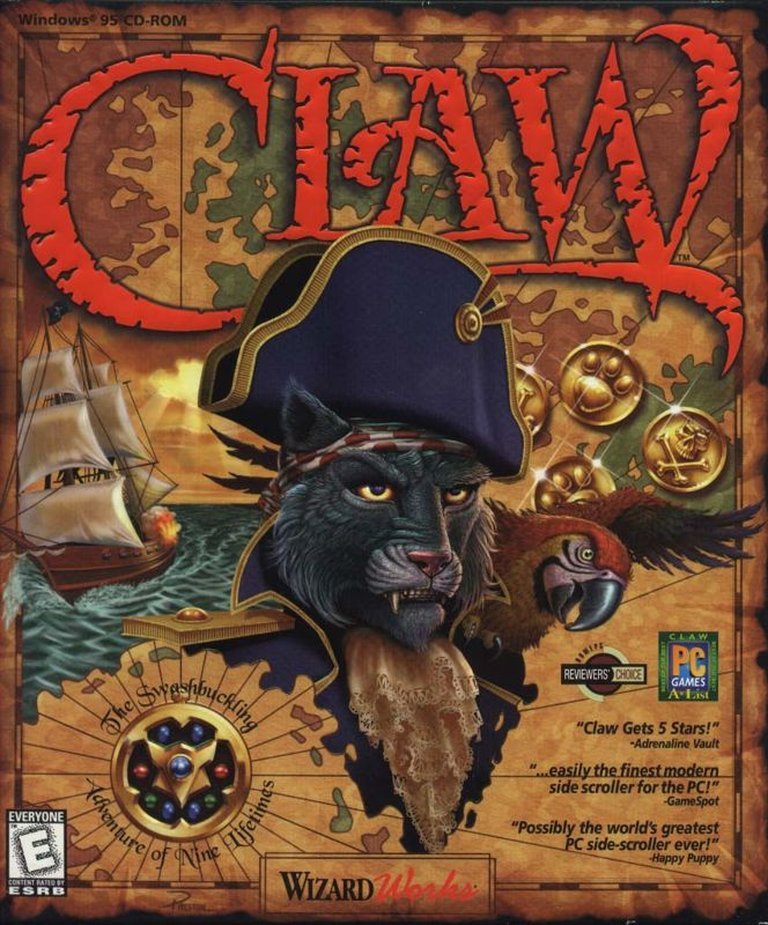

Captain Claw, an infamous feline pirate known as ‘The Surveyor of the Seven Seas,’ escapes prison after discovering a clue to the mystical Amulet of Nine Lives, embarking on a perilous quest through a 17th-century alternate world where cats and dogs dominate. This side-scrolling platform game challenges players to navigate diverse environments—from cities and forests to ships and underwater areas—using swords, pistols, dynamite, and magic to combat canine enemies, overcome hazards like traps and spikes, and solve puzzles in boss battles, all while collecting treasures and power-ups.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Claw

PC

Claw Free Download

Claw Mods

Claw Guides & Walkthroughs

Claw Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (88/100): My childhood memories. It was fantastic game and BGM is superb. When ever i play it brings back my memoreis of SUNDAY mornings times!!!!!

imdb.com (100/100): Pure nostalgia and good side scroll-gaming!

Claw Cheats & Codes

PC

Enter codes during gameplay in the cheat console.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| MPKFA | God mode |

| MPFPS | View frame rate |

| MPPOS | View coordinates |

| MPSTOPWATCH | View elapsed time |

| MPSPOOKY | Claw becomes a ghost |

| MPHAUNTED | Enemies become ghosts |

| MPWIMPY | Claw becomes weaker |

| MPBUNZ | Stronger claw |

| MPLITH | Enable Monolith logos and music |

| MPMONOLITH | Enable Monolith logos and music |

| MPLOGO | Enable Monolith logos and music |

| MPPLAYALLDAY | Unlimited lives |

| MPJORDAN | Super jump |

| MPSUPERTHROW | Super-throw mode |

| MPLOADED | Full ammunition |

| MPAPPLE | Full health |

| MPCASPER | Invisibility |

| MPPENGUIN | Ice Sword |

| MPFRANKLIN | Lightning Sword |

| MPHOTSTUFF | Fire Sword |

| MPFREAK | Catnip Mode |

| MPGANDALF | Full magic |

| MPOBJECTS | Display object count |

| MPNOINFO | Toggle object, frame rate, position, and time displays |

| MPMOONGOODIES | Toggle Moongoodies |

| MPSHADOW | Shadow mode |

| MPBOTLESS | Toggle back display plane |

| MPMIDLESS | Toggle middle display plane |

| MPTOPless | Toggle top display plane |

| MPINCVID | Increase resolution |

| MPDECVID | Decrease resolution |

| MPDEFVID | Default resolution |

| MPJAZZY | 320×200 resolution |

| MPGOBLE | “Brian L. Goble” message |

| MPSCORPIO | “Brian L. Goble” message |

| MPDEVHEADS | View developers’ heads as treasure |

| MPBLASTER | Full dynamite |

| MPSCULLY | Skip current level |

| MPVADER | Invincibility |

| MPCHEESESAUCE | Advance to level 1 |

| MPEXACTLY | Advance to level 2 |

| MPRACEROHBOY | Advance to level 3 |

| MPBUDDYWHAT | Advance to level 4 |

| MPMUGGER | Advance to level 5 |

| MPGOOFCYCLE | Advance to level 6 |

| MPROTARYPOWER | Advance to level 7 |

| MPSHIBSHANK | Advance to level 8 |

| MPWHYZEDF | Advance to level 9 |

| MPSUPERHAWK | Advance to level 10 |

| MPJOBNUMBER | Advance to level 11 |

| MPLISTENANDLEARN | Advance to level 12 |

| MPYEAHRIGHT | Advance to level 13 |

| MPCLAWTEAMRULEZ | Advance to level 14 |

| MPSKINNER | Go to boss warp |

| MPMOULDER | Return to previous level |

| MPROIDS | Roids on |

| MPMERLIN | Full magic |

| MPRAMBO | Full ammo |

| MPARMOR | Anti-death tile is on |

| MPPREV | Previous level |

| MPNEXT | Next level |

| MPTIMING | Displays info in top left |

| MPUPDATE | Displays more info in top left |

| MPINFINITY | Can’t lose lives |

| MPFLUBBER | Superjump mode |

| MPNIPPY | Jump higher |

| MPSAVE | All levels |

Claw: A Feline Swashbuckler’s Timeless, Torturous Triumph

Introduction: The Purr-plexing Legacy of a Cult Classic

In the vast, often-overlooked archives of PC gaming history, few titles evoke such a potent mix of affectionate reverence and sheer, unadulterated frustration as Monolith Productions’ 1997 side-scroller, Claw. Released in the same year as the studio’s famously ultraviolent Blood, Claw represented a deliberate and stunning pivot—a family-friendly, artistically rich, and mechanically demanding platformer that stood in stark contrast to the 3D revolutions of Super Mario 64 and Tomb Raider. It was a game that felt both nostalgically rooted in 16-bit era design and ambitiously modern in its presentation. My thesis is this: Claw is not merely a well-crafted platformer; it is a fascinating, flawed, and ultimately brilliant artifact of its time. Its legacy is defined by a sublime marriage of cartoonish artistry and punishing, puzzle-oriented gameplay, a combination that cultivated a fiercely dedicated community while simultaneously limiting its mainstream impact. To play Claw is to engage with a game that is unequivocally of the late 1990s yet possesses a timeless charm and challenge that resonates, for better or worse, to this day.

Development History & Context: Monolith’s Counter-Intuitive Pivot

Claw emerged from Monolith Productions, a studio rapidly building a reputation for genre-pushing intensity. Having just unleashed the Build engine-powered mayhem of Blood in May 1997, the decision to develop a whimsical, all-ages platformer was a bold, almost schizophrenic, creative swing. Led by Creator/Designer Garrett Price and a team that included key engineers Brian L. Goble and John LaCasse, the project was built upon the studio’s proprietary Windows Animation Package 32 (WAP32) engine. This technology, first seen in Goble’s shareware title The Adventures of Microman, was a sophisticated 2D parallax scroller that allowed for smooth, multi-layered backgrounds and fluid sprite animation on Windows PCs—a significant technical achievement that gave Claw a visual polish rarely seen in PC platformers.

The gaming landscape of 1997 was dominated by the nascent 3D revolution. The notion of a major PC developer investing in a traditional 2D platformer was considered commercially questionable. Yet, as noted in Computer Games Magazine, CEO Jason Hall explicitly intended Claw to fill a “non-violent” niche, positioning it as family-friendly entertainment. This context is crucial: Claw was an act of defiance against the graphical arms race, a belief that exemplary art design, tight gameplay, and charm could still triumph. Its development was also intertwined with early online multiplayer ambitions. It was one of the first games to utilize a network jointly created by Microsoft and NANI, originally touting support for a staggering 256 players—a feature that, while technically present in a limited form (supporting up to 64), became a legendary but rarely experienced footnote due to the logistical challenges of the era.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Pirate’s Code in a World of Anthropomorphic Politics

The plot of Claw is a delightful pastiche of pirate tropes and classic adventure serials, elevated by a surprisingly robust lore. We follow Captain Nathaniel Joseph Claw, a renowned grey cat pirate whose raids on the “Cocker-Spaniard” kingdom have infuriated the canine monarchy. After a naval battle orchestrated by Admiral Le Rauxe results in the sinking of his ship, Claw is imprisoned in the fortress-like jail La Roca (“The Rock”). Here, the narrative engine ignites: Claw discovers a letter from a previous inmate, Edward Tobin, detailing the Amulet of Nine Lives, a mystical artifact granting near-immortality to anyone who collects its nine gems.

This MacGuffin launches Claw on a globe-trotting quest that dexterously uses gameplay hubs to advance the story. The narrative is delivered through approximately 20 minutes of exquisitely hand-drawn, cartoon-style cutscenes—a rarity for the genre and a huge selling point. These scenes, praised for their cinematic quality, give the world and its characters a tangible weight. The quest structure is episodic and efficient: escape La Roca, traverse the Dark Woods (ruled by his former lover, the bandit Katherine), battle through the Township and El Puerto del Lobo under the tyrannical rule of Magistrate Wolvington, infiltrate the ship of his arch-nemesis Red Tail (a tiger pirate), navigate the Pirates’ Cove to confront his old friend-turned-rival Marrow, descend into the Undersea Caves to defeat the frog-like demigod Aquatis, and finally storm Tiger Island and its lava-filled Temple to face the final guardian, Omar.

Thematically, the game explores classic motifs: revenge, legacy, and the pursuit of mythical power. The feline vs. canine conflict provides a simple but effective allegory for political strife. The cutscenes and dialogue (voiced with panache by Stephan Weyte, also the voice of Blood‘s Caleb) imbue Claw with a cocky, witty personality that was groundbreaking for a silent-era-adjacent protagonist. His idle quips (“At least bring me something back from the kitchen!”) and the Shakespearean boasts of the town guards create a world with a distinct, playful personality. The story culminates not with a grand ideological victory, but with the personal acquisition of the Amulet and the swearing of Omar as Claw’s bodyguard—a classic reward for the player’s perseverance, cementing Claw’s status as aLegendary figure within his own mythos.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Refinement Over Revolution

If Claw’s narrative is its heart, its gameplay is its meticulously crafted skeleton. It does not invent new mechanics; instead, it perfects the established language of 2D platforming with an almost obsessive level of polish.

Core Loop & Movement: The control scheme is a masterclass in responsiveness. Claw moves with a satisfying weight, can stop on a dime, and his jump trajectory is precise and predictable. His basic toolbox is elegant: a sword (primary melee), a punch/kick (faster, unblockable close-range), a flintlock pistol (limited ammo), dynamite (arcing projectile), and the Magic Claw spell (homing projectiles, extremely rare). The genius lies in how these tools are gated and encouraged. Ammo is scarce, forcing players to rely on melee, but special items like the Fire, Frost, and Lightning Swords (temporary beam attacks) or Catnip (a significant stat boost) are often placed in hard-to-reach areas, creating natural progression loops based on acquiring power-ups to access more treasure and secrets.

Level Design & Puzzle Integration: The 14 levels are massive, sprawling affairs that function as intricate puzzle boxes. They are not merely gauntlets of jumps and enemies but interconnected spaces filled with hidden passages, warp portals, and treasure (coins, gold bars, crowns) locked behind precise platforming challenges. The design philosophy is one of “reward for observation and execution.” Secret areas are rarely telegraphed, often requiring Leaps of Faith or the use of a recently acquired power-up to access. This creates immense replay value for completionists but also immense frustration for those seeking 100%.

Combat & Bosses: Enemy variety is a standout. From the lowly Mice (annoying, explosive) and Seagulls (aggravating tackle attacks) to the sword-wielding Guard Dogs, Peg Leg Pirates, and the fearsome Bear Sailors (with their deadly “Killer Bear Hug”), each foe type behaves differently. Many can block, parry, or dodge, making combat a tactical consideration rather than a button-mash. Boss fights are the pinnacle of this design. They are less about reflexive dodging and more about pattern recognition and puzzle-solving.

* Catherine (Level 4) requires you to defeat her in a small arena with limited attack windows.

* Wolvington (Level 6) is a projectile-heavy magician who blocks relentlessly.

* Gabriel (Level 8) is a classic Puzzle Boss: you must use his own cannon against him by knifing its direction switch.

* Marrow (Level 10) phases out behind a spike pit after 25% damage, forcing you to deal with his vicious parrot three times before you can continue.

* Aquatis (Level 12) requires dynamite to dislodge stalactites onto his head.

* Omar (Level 14) is a legendary Marathon Boss, cycling through elemental shields (fire/ice) that require you to brave lava-filled corridors to fetch the opposite sword, all while dodging energy balls. This fight is the ultimate test of everything the game has taught you.

Save System & Difficulty: This is the game’s most infamous and divisive mechanic. Each sprawling level contains only two save points (represented by Jolly Roger flags). Combined with a limited life pool (extra lives are awarded at score milestones, initially every 1,000,000 points, but patched to 500,000), this creates a punishing, old-school difficulty. As critic Maw brilliantly observed, “Two save points doesn’t feel like nearly enough… you usually have to march across massive amounts of territory just to get back.” The difficulty is not cheap—it stems from the intricate, challenging puzzles and precise platforming—but the save system turns failure into a significant time penalty. This is a deliberate, masocore-oriented design choice that defines the Claw experience, for better or worse.

Multiplayer & Level Editor: Claw ambitiously included an Internet multiplayer mode for up to 64 players, a stunning feature for a 2D platformer. Modes involved cooperative or competitive play, racing to finish levels or collecting the most loot, with “Claw Curses” to sabotage opponents. While a logistical curiosity in 1997 due to connection limitations, its inclusion was visionary. More impactful was the included level editor (WapWorld). This tool, while not user-friendly, spawned a vibrant, enduring modding community. For decades, fans have created hundreds of custom levels, some rivaling the official content in quality, ensuring Claw‘s longevity far beyond its 14-base levels. As one reviewer noted, this decision was “probably one of the smartest they made.”

World-Building, Art & Sound: ACartoon Come to Life

Claw’s most universally praised aspect is its artistic presentation. The sprites are not pixel-art in the traditional sense but are hand-drawn, painterly, and brimming with personality. Environments are rich and layered: the grim, torch-lit stone of La Roca, the leafy, swampy Dark Woods, the bustling, terraced architecture of El Puerto del Lobo, the chaotic rigging of Red Tail’s ship, and the lava-drenched, trap-laden Tiger Temple. Each area feels distinct and alive, with background details and parallax scrolling that create a sense of depth uncommon in 2D games.

The animation is particularly ahead of its time. Claw has contextual animations for almost every action: he wobbles precariously on platform edges, grimaces during attacks, heaves when throwing barrels, and crosses his arms while idling. Enemies, too, are full of character—from the preening Gabriel and his hand-mirror to the bearish, dim-witted Sailor Bears. The cutscenes, rendered in the same style at higher resolution (especially on the DVD edition), tell the story with a genuine Saturday morning cartoon sensibility.

The sound design and music are equally integral. Composed by Daniel Bernstein and Guy Whitmore, the soundtrack features lush, thematic orchestral arrangements that evoke pirate adventure, mystery, and tension. Each major level has its own musical identity. Sound effects are crisp and cartoony: the clang of swords, the thud of a thrown enemy, the crack of the pistol, and the memorable splash of treasure hitting the ground. Critically, Claw’s voice, provided by Stephan Weyte, is a defining feature. His lines are frequent, witty, and perfectly delivered, giving the silent protagonist of most platformers a voice and attitude that players remember decades later. As TV Tropes notes, this combination of aesthetics creates a world that feels “timelessly beautiful.”

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic Forged in Difficulty

Upon release in September 1997, Claw received mixed-to-positive reviews, aggregating to a 81% critic score on MobyGames. The praise was effusive for its artistry, sound, and level design. Adrenaline Vault gave it a perfect 5/5, calling it “intense.” GameSpot declared it “easily the finest modern side scroller available for the PC,” highlighting its 64-player mode. AllGame compared its enjoyment value to Super Mario and Crash Bandicoot. The criticisms were almost uniformly focused on two points: the exorbitant difficulty coupled with the stingy save system and the feeling that, mechanically, it was a refinement rather than an innovation in a year of 3D leaps. PC Gamer’s 65% review lamented its lack of the “humor” or “gore” of Monolith’s other titles, while PC Powerplay famously suggested it “might have been an excellent 3D platformer.”

Commercially, it was overshadowed by contemporaries like Jazz Jackrabbit 2, as noted by fan critic Maw. However, its true legacy was forged in the years that followed. The ease of modding via the level editor created a self-sustaining community. Websites like “The Claw Recluse” and “Captain Claw’s Lair” became hubs for custom levels, walkthroughs, and patches. This community remains active in 2025, with new levels and compatibility fixes for modern systems (like the excellent dgVoodoo-based installer from The Collection Chamber) still being released. This enduring mod support is the ultimate testament to the strength of its core level design tools.

The game’s difficulty, initially a barrier, became a badge of honor. Speedrunning communities emerged, exploiting sequence breaks and techniques to conquer its punishing stages. Retrospective reviews, like Anthony Burch’s on Destructoid, softened, praising its accessibility and fun while acknowledging the high skill floor. It is now rightfully considered a cult classic, a game that “could have come out this year, and it could very well have been in contention for indie game of the year,” as one modern revisit argued. Its influence is subtler than some contemporaries; it didn’t spawn a genre, but it proved that a PC-exclusive, hand-crafted 2D platformer with serious depth could still find its devoted audience.

A postscript to its legacy involves a scrapped sequel. Around 1999, Monolith began work on Captain Claw 2 in 3D using the fledgling LithTech engine. Due to unspecified copyright issues with the character, the project was abandoned. The assets were passed to Polish developer Techland, who attempted to revive it as Captain Claw 2 (2007), then Jack, the Pirate Cat, and finally Nikita: The Mystery of the Hidden Treasure (2008)—a game that bore no relation to the original. This orphaned sequel effort is a poignant end to the official history, leaving the 1997 original as a singular, untouched masterpiece.

Conclusion: An Imperfect Jewel in Gaming’s Crown

Claw is a game of profound contradictions. It is a family-friendly title with the soul of a hardcore challenge. It is a 2D game released at the dawn of 3D, yet its environmental storytelling and animation feel more advanced than many of its polygonal peers. It is a commercial footnote that cultivated a community more passionate and long-lasting than many AAA titles.

Its flaws are indelible: the save system is punitive to a fault, the difficulty curve is wildly inconsistent (Level 2’s battlements are infamous as harder than Level 3, the Level 6 boss Wolvington is a notorious roadblock), and its performance could be demanding for the era’s mid-range PCs. Yet, to dismiss it for these reasons is to miss its monumental achievements. Claw is a game built on respect for the player’s intelligence and dexterity. It rewards patience, observation, and mastery in a way few games do. Its world is a joy to inhabit, its protagonist a legendary figure of personality, and its levels are intricate puzzles of platforming and combat that feel like genuine discoveries.

In the pantheon of platformers, Claw may not have the ubiquitous fame of Mario or the technical bravado of Rayman, but it occupies a sacred space for those who seek a specific kind of experience: one where artistry and brutality intertwine, where every jump feels earned, and where a pirate cat’s quest for nine lives can consume a week of your own. It is a masterpiece of its ilk—a tough, beautiful, and impeccably designed adventure that stands as one of the finest, most idiosyncratic side-scrollers ever created for the PC. To play Claw is to engage with a piece of gaming history that is as frustrating as it is magnificent, a testament to the idea that sometimes, the most memorable journeys are the ones that test your resolve at every single, beautifully drawn step.