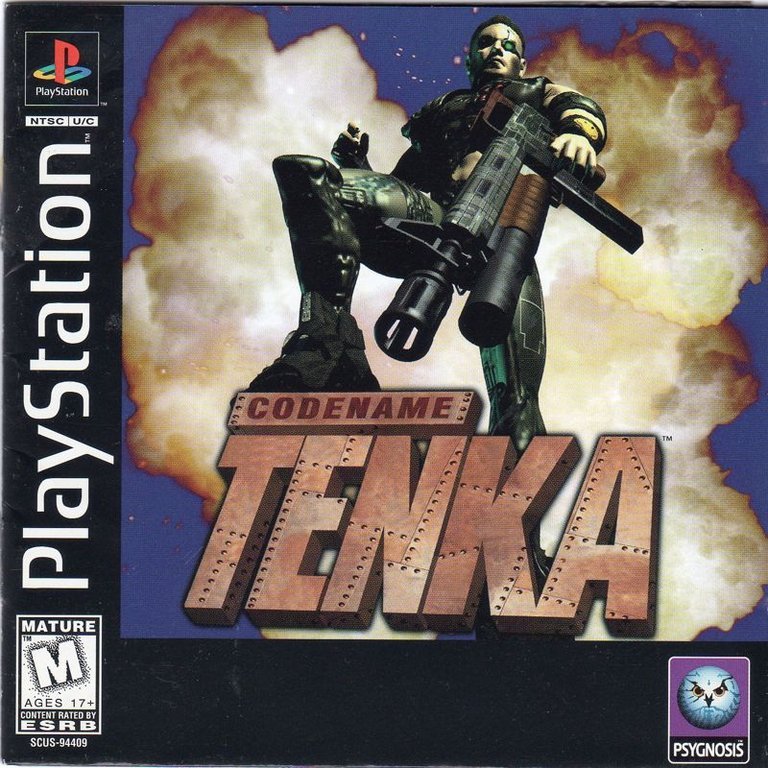

- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: PlayStation, Windows

- Publisher: Psygnosis Limited

- Developer: Psygnosis Limited

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Post-apocalyptic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 65/100

- Adult Content: Yes

Description

Set in the post-apocalyptic year of 2096, Codename: Tenka is a first-person shooter where players assume the role of Joseph B. Tenka, a future ‘Bionoid’ warrior. Unhappy with the corporate conglomerate’s plans to manufacture deadly warriors and abandon a war-torn Earth, Tenka embarks on over 20 missions to stop these evil plans. The game is a Doom-style clone renowned for its creepy, Aliens-inspired atmosphere and detailed mission briefings.

Codename: Tenka Free Download

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

ign.com (70/100): Does the world really need another first-person shooter? If it’s Tenka, then yes

gamespot.com (61/100): If you just can’t get enough first-person shooter action, you may want to check out Codename: Tenka – it’s one of the better ones out there.

mybrainongames.com : time has not been kind to the PlayStation version for one unforgivable reason: atrocious controls

Codename: Tenka: A Relic of the Post-Apocalypse Lost in the Fog of War

In the annals of video game history, certain titles are remembered not for their revolutionary success, but for their embodiment of a specific moment in time—a snapshot of technological ambition, genre conventions, and the harsh realities of commercial execution. Psygnosis’s 1997 first-person shooter, Codename: Tenka (known in Europe as Lifeforce Tenka), is one such artifact. A game caught between the shadow of Doom and the dawn of a new era for 3D action, it is a fascinating, flawed, and ultimately forgotten piece of the PlayStation’s formative years.

Introduction

The year is 2096. Earth is a polluted, war-torn husk, and the promise of a new life on an off-world corporate colony is a lie masking a horrific truth: you are merely raw material for a army of biomechanical soldiers. You are Joseph B. Tenka, and you are very unpleased. This was the pitch for Codename: Tenka, a game that promised a gritty, atmospheric journey into a corporate dystopia. While it delivered on atmosphere with a striking visual style and an exceptional industrial soundtrack, it was hamstrung by one of the most notoriously archaic control schemes of its generation. This review will argue that Tenka is a classic case of a game whose ambitious aesthetic and technical ideas were tragically undermined by fundamental gameplay failures, leaving it as a compelling, yet frustrating, footnote in the legacy of both Psygnosis and the first-person shooter genre.

Development History & Context

To understand Codename: Tenka, one must first understand its creator. By 1997, Liverpool-based Psygnosis was a jewel in Sony Computer Entertainment’s crown, having been acquired just a few years prior. The studio was renowned for its technical prowess and artistic flair, evidenced by the sleek, futuristic anti-gravity racer WipEout and the soon-to-be-released space combat epic Colony Wars. Development on Tenka began in earnest in January 1995, a period of frantic experimentation as developers learned to harness the PlayStation’s unique capabilities.

The team, led by Director of Development Adrian Parr and Head Producer Morgan O’Rahilly, aimed high. Senior Programmer Martin Linklater detailed the technological challenges in contemporary previews. The PlayStation lacked hardware support for perspective-correct texture mapping, which often resulted in the infamous “wobbly” textures seen in early 3D games. Psygnosis’s solution was a “dynamic multistage clipping and meshing system” designed to minimize this warping effect—a significant technical achievement for the time. The game’s graphics were crafted using the high-end Softimage 3D software, with the team writing custom utilities to extract the models and environments for the game engine.

The gaming landscape at the time of its May 1997 release was fiercely competitive. id Software‘s Doom had defined the FPS genre on PC, and its spiritual successor, Quake, had launched the previous year, raising the bar for 3D visuals. On consoles, the genre was still finding its footing. Tenka was positioned as a PlayStation-exclusive experience that could deliver a Doom-like intensity with a distinct, cinematic Aliens vibe. However, in a critical decision that would haunt its reception, the team opted to focus solely on a single-player experience, forgoing any multiplayer component. As Linklater stated, “We have chosen to concentrate on a single-player game – which would be the most played version anyway.” This was a miscalculation in a era where deathmatches were becoming a primary driver of the genre’s longevity.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of Codename: Tenka is a quintessential piece of 90s cyberpunk schlock, delivered with a completely straight face. Trojan Incorporated, a sinister multinational conglomerate, is luring the last remnants of humanity to its off-world colony, Extrevius 328, with promises of paradise. In reality, it is a processing plant where colonists are subjected to illegal genetic experiments, merging them with alien DNA to create an army of “Bionoid” warriors.

The protagonist, Joseph D. Tenka, is a classic archetype: the disgruntled, wronged everyman who becomes a hard-as-nails avenger. With a gruff voice and a perpetually bad attitude, he was clearly modeled after the era’s action heroes, most notably Duke Nukem. The story unfolds through pre-rendered cutscenes that, while dark and grainy, were impressive for their cinematic ambition on the PlayStation. They provide glimpses into Tenka’s psyche, painting him as a man consumed by a headache-inducing rage against the corporate machine.

Thematically, the game taps into potent fears of corporate overreach, the loss of humanity to technology, and the ethical nightmare of genetic manipulation. It’s a bleak, post-apocalyptic vision where Earth is beyond saving and the promise of a new beginning is merely a more sophisticated form of exploitation. While these ideas weren’t novel even in 1997, Tenka‘s commitment to its grim atmosphere through visual and audio design gave its B-movie plot a surprising amount of weight. It wasn’t just about shooting mutants; it was about dismantling a system that saw human life as a commodity.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

This is where Codename: Tenka‘s legacy fractures. At its core, it is a straightforward first-person shooter with a progression loop familiar to any Doom veteran: navigate maze-like, multi-level environments, find colored keycards, defeat a boss, and progress to the next mission. However, several mechanics set it apart, for better and overwhelmingly for worse.

The Infamous Control Scheme: The most immediate and damning flaw is the control system. Releasing mere weeks before the PlayStation Dual Analog Controller, Tenka was designed for the standard digital pad. It utilizes what critics and players have since dubbed “tank controls.” The directional pad moves Tenka forward/backward and turns him left/right. Looking up and down is mapped to the L1 and L2 buttons, a configuration described by reviewers as “unintuitive” and by modern players as “atrocious.” The preset control configurations offered no improvement, and there was no option for customization. This design made combat, especially against fast, hovering enemies, an exercise in frustration. Players often found it easier to stand completely still and duel foes rather than attempt to maneuver, a fatal flaw for an action game.

The SG-26 Polymorphic Weaponry: One of the game’s most innovative ideas was its approach to arsenal. Instead of collecting disparate weapons, Tenka is equipped with the “Self-Generating Polymorphic armoury,” or SG-26. This base weapon evolves by collecting neon green cubes dropped by defeated enemies, gradually adding new functionalities like laser sights, missile launchers, and explosive charges. This morphing weapon was a novel concept, encouraging players to adapt their toolset to different combat scenarios.

The Crouch Mechanic: As Glenn Rubenstein of GameSpot famously noted, the game’s most distinguishing feature was its ability to crouch. This allowed Tenka to crawl through air ducts and low passages, adding a slight element of verticality and exploration to the level design. In an era where most FPS protagonists were permanently upright, this was a small but noteworthy innovation.

Difficulty and Objectives: Tenka was universally recognized as a challenging game. The levels were expansive, dark, and often confusing to navigate without an in-game map. Objectives were sometimes obscure, leading players to rely on walkthroughs to understand what to do next. The enemy AI was not sophisticated, but the combination of awkward controls, relentless foes, and labyrinthine level design created a significant barrier to entry. The combat loop, criticized by many as simplistic and repetitive, failed to hold interest through its 20 missions.

World-Building, Art & Sound

If the gameplay was Tenka‘s greatest weakness, its atmosphere was its undeniable strength.

Visual Design & Art Direction: Psygnosis’s artistic pedigree is on full display. The game’s environments are a masterclass in bleak, industrial sci-fi. Drawing direct comparison to Aliens, the levels are a network of grimy, metallic corridors, dank ventilation shafts, and ominous industrial complexes. The lighting effects were frequently praised by contemporary critics; dynamic shadows and moody, colored lightsources created a palpable sense of dread and immersion. The use of fully 3D polygonal enemies was also a technical feat on the PlayStation, even if their animations were sometimes described as jerky or “like hamplmen.” The enemy designs themselves were a highlight—bizarre, gruesome biomechanical horrors that left a strong impression.

Sound Design & Soundtrack: This is the aspect of Tenka that has aged the most gracefully. The sound design is serviceable, with satisfying weapon reports and unsettling enemy noises, but the true star is the soundtrack. Composed primarily by Mike Clarke, it is a powerhouse of 90s industrial metal and techno. Tracks like “Joey Does Dallas” and “A Hammer” sound like lost cuts from Nine Inch Nails or Ministry. Psygnosis embraced the CD format, including a full audio track listing in the manual, and the music is not just background noise; it is a driving, integral part of the experience. The soundtrack alone is a compelling reason to revisit the game’s legacy.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its release, Codename: Tenka received a mixed-to-positive critical reception, though a stark divide emerged between platforms.

The PlayStation version fared better, earning a MobyScore of 7.3 based on 15 reviews. Publications like Fun Generation (90%) and Mega Fun (85%) praised its atmosphere, lighting, and solid shooter action, though many noted its high difficulty and derivative nature. The PC version, released a year later in 1998, was eviscerated. With a dismal MobyScore of 5.5, it was criticized as a lazy, poorly optimized port. German magazine PC Games gave it a 10%, lambasting its “sloppy console conversion” and “completely botched controls.”

The consensus was clear: the game was a technical showcase for its art and sound, but its gameplay failed to innovate meaningfully beyond its crouching mechanic. As Edge magazine summarized, “all these new degrees of freedom have rarely managed to produce an experience as immersive and atmospheric as the strictly eyes-first Doom. Tenka is a case in point.”

Its legacy is faint. It was not a commercial smash that spawned sequels, nor did it revolutionize its genre. Its influence is negligible, a testament to a project that couldn’t overcome its core design flaws. However, it remains a fascinating time capsule—a example of a talented studio applying its signature style to a popular genre and stumbling on the most fundamental element: fun, accessible control.

Conclusion

Codename: Tenka is a game of profound contrasts. It is a title crafted with obvious technical skill and artistic passion, boasting a world that feels genuinely oppressive and a soundtrack that absolutely slays. Yet, it is fundamentally broken by a control scheme that transforms its core action from thrilling to tedious. It is a beautiful, haunting, and deeply frustrating experience.

For historians and collectors, it represents a specific moment in Psygnosis’s evolution and the PlayStation’s library—a ambitious but flawed experiment from a studio capable of true greatness. For the average player, it is likely best left as a memory, a game whose promise is buried under layers of archaic design. Its place in video game history is not on the main stage, but in the wings: a cautionary tale that the most stunning visuals and atmospheric sound cannot save a game if it isn’t satisfying to play. Codename: Tenka is a relic, a ghost in the machine whose potential was never fully realized.