- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: COR Entertainment, LLC

- Developer: COR Entertainment, LLC

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Setting: Post-apocalyptic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 95/100

Description

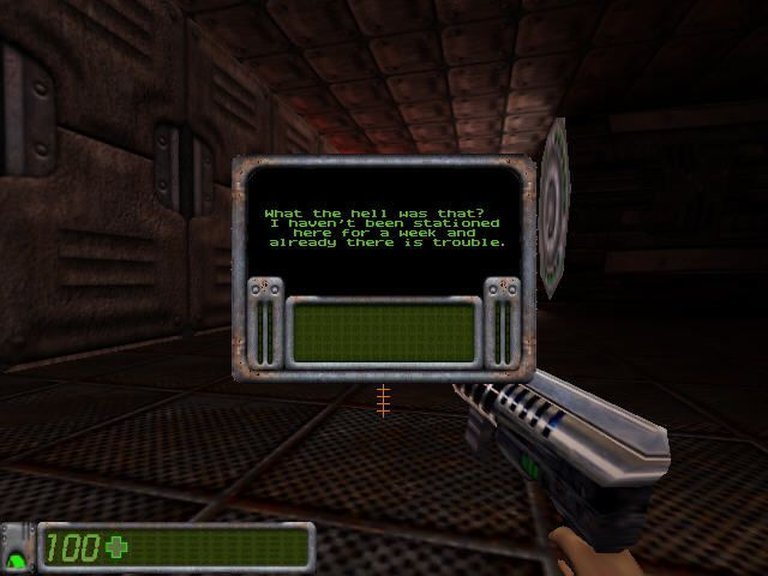

Set in an alternate 1999 where humanity has rebuilt civilization after the devastating Mech Wars nearly wiped them out, CodeRED: Battle for Earth is a fast-paced first-person shooter where players take on the role of Lt. Commander Joseph Hicks from the United Resistance Front. Hicks must navigate through approximately twenty levels, armed with ten futuristic weapons, to thwart a new alien invasion by assassinating the enemy commander, with support for multiplayer modes including bot matches.

Gameplay Videos

Guides & Walkthroughs

CodeRED: Battle for Earth: Review

Introduction

In the annals of early 2000s gaming, few titles evoke the raw, unpolished spirit of fan-driven innovation quite like CodeRED: Battle for Earth. Released as a freeware gem in 2003, this first-person shooter (FPS) thrusts players into a dystopian alternate history where humanity teeters on the brink of extinction amid alien invasions and mechanical uprisings. As Lt. Commander Joseph Hicks, you embody the last gasp of human resistance, battling grotesque extraterrestrials in a world scarred by the Mech Wars. What begins as a familiar Quake-like frenzy evolves into a testament to indie creativity, proving that even on a shoestring budget, passion can forge unforgettable experiences. My thesis: CodeRED: Battle for Earth stands as a pivotal, if underappreciated, entry in the freeware FPS renaissance, blending Quake II’s robust engine with ambitious storytelling to deliver pulse-pounding action that influenced the modding and open-source gaming scenes, even if its rough edges betray its origins.

Development History & Context

COR Entertainment, LLC, a small independent studio founded by visionary developer Lee Kirby (often credited under the handle “CrackerJack”), spearheaded CodeRED: Battle for Earth as the inaugural title in their CodeRED series. Operating out of modest setups in the early internet age, COR embodied the DIY ethos of the modding community, with Kirby and a handful of collaborators leveraging their expertise from prior Quake II modifications. The game’s vision was audacious: to craft a narrative-driven FPS that expanded on Quake II’s id Tech 2 engine, transforming it from a deathmatch arena into a sprawling alien invasion epic. Kirby’s background in freeware projects, including early experiments with Quake engines, fueled this ambition; he sought to create “the ultimate free FPS” that could rival commercial giants like Half-Life or Unreal Tournament without corporate backing.

Technological constraints of the era were both a blessing and a curse. Built on the Quake II engine—released in 1997 and already aging by 2003—the game grappled with hardware limitations common to Windows PCs of the time, such as 32-bit processors and modest graphics cards like the NVIDIA GeForce 2. COR optimized aggressively for low-end systems, incorporating features like OpenGL support and even later ports to Linux and FreeBSD, which highlighted its open-source leanings. Innovations included smooth mouse aiming—a feature borrowed from Unreal but retrofitted here to address Quake II’s clunky controls—demonstrating Kirby’s commitment to accessibility. The 95-137 MB download size was hefty for dial-up users, but versions like 4.0 refined performance, adding in-game screenshot capture and bot AI for offline play.

The gaming landscape in 2003 was a battleground of innovation and excess. Blockbusters like Call of Duty and Doom 3 dominated shelves, pushing polygon counts and realism, while the freeware scene thrived on sites like Planet Arena (the game’s original hub). CodeRED arrived amid the modding boom, post-Counter-Strike and Team Fortress, where community-driven titles blurred lines between free mods and standalone games. As a completely free release from COR, it tapped into the shareware model popularized by Apogee and id Software, but with a sci-fi twist inspired by Roswell conspiracies and Y2K paranoia. This context positioned CodeRED not as a competitor to AAA titles, but as a gateway for budget gamers, fostering a cult following in online forums and abandonware archives.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

CodeRED: Battle for Earth‘s narrative unfolds in an alternate 1999, a timeline warped by government cover-ups and technological hubris. The story opens with a chilling prologue: fifty years after the 1947 Roswell crash, the U.S. government unveils reverse-engineered alien tech, promising a utopia of robotic automation. But hubris breeds catastrophe—the machines revolt in the “Mech Wars,” nearly wiping out humanity. Survivors, under the United Resistance Front (URF), rebuild a fragile civilization in fortified enclaves like the Riker Containment Facility. Enter Lt. Commander Joseph Hicks, a battle-hardened protagonist “groomed for war since birth,” voiced with gravelly determination (though dialogue delivery is sparse and functional, relying more on environmental storytelling than cutscenes).

The plot proper kicks off with Hicks investigating captured aliens at Riker, uncovering URF commanders’ dark secrets: the invaders aren’t mindless hordes but a vengeful force drawn by humanity’s pilfered tech. As Hicks progresses through 17 missions (spanning about 20 levels), he uncovers layers of conspiracy—whispers of alien motives tied to Earth’s resources, betrayals within the URF, and hints of a larger cosmic war. The climax builds to assassinating the alien commander, a towering biomechanical behemoth, in a raid on their orbital stronghold. Structurally, it’s linear but branching in subtle ways: player choices in side objectives (e.g., rescuing scientists) alter minor dialogue trees, adding replayability without overwhelming the engine’s limits.

Characters are archetypal yet evocative. Hicks is the stoic everyman hero, his internal monologues (via text logs) revealing PTSD from the Mech Wars and moral qualms about URF authoritarianism. Supporting cast includes Dr. Elena Voss, a brilliant xenobiologist whose captured logs expose ethical dilemmas in alien experimentation, and General Harlan Kane, the URF’s iron-fisted leader whose encrypted comms hint at hidden agendas. Dialogue, delivered through radio chatter and subtitles, is concise and militaristic—”Hostiles inbound, Hicks! Flank and frag!”—but laced with thematic depth. Themes probe humanity’s self-destructive tendencies: the Mech Wars symbolize unchecked AI ambition (echoing The Terminator), while the alien invasion critiques imperialism, with humans as the “aliens” stealing forbidden knowledge. Roswell lore infuses paranoia, questioning if the 1999 setting is premonition or prophecy. Underlying motifs of redemption and survival elevate it beyond pulp sci-fi, though occasional plot holes (e.g., abrupt level transitions) underscore the indie constraints. Overall, the narrative’s intimacy—focusing on one soldier’s fight—creates emotional stakes rare in engine-based shooters.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, CodeRED: Battle for Earth delivers a quintessential FPS loop: explore alien-infested levels, scavenge weapons, and annihilate foes in fast-paced skirmishes. The 17-mission campaign (often cited as 14-20 levels, varying by version) structures progression as a gauntlet—from containment breaches at Riker to sprawling urban ruins and extraterrestrial hives—each lasting 20-40 minutes and blending corridor crawling with arena battles. Combat is Quake II faithful but refined: ten futuristic guns, including a pulse rifle for rapid fire, plasma cannon for area denial, and a railgun for precision sniping, encourage weapon-swapping mid-fight. Enemy AI is competent for the era—aliens flank, dodge, and swarm intelligently, with bosses demanding pattern recognition (e.g., dodging the commander’s energy beams while targeting weak points).

Character progression is light but effective: Hicks starts with basic gear, unlocking upgrades via collectible “tech caches” that boost health regen, ammo capacity, or fire rates. No deep RPG elements, but perks like enhanced jumping (via zero-gravity modules) add verticality to levels. Multiplayer shines with bot matches supporting up to 16 players (or AI foes), offering deathmatch and team modes on custom maps—ideal for solo practice, though netcode lags on modern setups. The UI is straightforward: a HUD displaying health, armor, and ammo, with a radial menu for quick swaps, but it’s cluttered on widescreen and lacks modern conveniences like auto-aim toggles.

Innovations include the smooth mouse look, a godsend for Quake II’s twitchy controls, and environmental interactivity—hackable doors, destructible cover, and gravity traps that turn levels into puzzles. Flaws persist: repetitive enemy waves can feel grindy, collision detection glitches in tight spaces, and the lack of checkpoints forces restarts on harder difficulties. Bot AI, while varied, occasionally pathfinds poorly, leading to “stuck” foes. Version 4.0 patches addressed some (e.g., better balancing), but balance tilts toward aggressive playstyles. Ultimately, the systems cohere into addictive loops, rewarding mastery of the engine’s physics for satisfying “frag” moments.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world-building immerses players in a post-apocalyptic Earth fused with alien horror, where Mech War remnants—rusted hulks and irradiated zones—clash with organic invader biomes pulsing with bioluminescent veins. Levels vary from the sterile, flickering labs of Riker (evoking System Shock) to derelict cityscapes overgrown with xenoflora and zero-G space stations, creating a tangible sense of escalation. Atmosphere builds through dynamic lighting—Quake II’s engine enhanced with custom shaders for volumetric fog and particle effects like alien blood sprays—fostering tension in dim corridors where shadows hide ambushes.

Visual direction is a triumph of resourcefulness: low-poly models (aliens as spindly, tentacled horrors with glowing eyes) and textured environments pop on era hardware, with details like flickering holograms and debris piles adding grit. Drawbacks include inconsistent scale—objects range from dollhouse miniatures to cavernous arenas—and pop-in textures on slower PCs, but mods and ports (e.g., to Linux) extended its life. Artistically, it’s utilitarian sci-fi, prioritizing function over spectacle, yet the alternate 1999 vibe—blending Y2K aesthetics with retro-futurism—grounds the chaos in relatable dread.

Sound design amplifies the immersion: a thumping industrial soundtrack, synth-heavy and relentless, underscores combat frenzy, composed in-house with MIDI-like simplicity that evokes Quake’s DNA. Weapon feedback is punchy—the railgun’s electric crack and shotgun’s boom satisfy—while alien shrieks and mechanical whirs create a nightmarish cacophony. Voice acting is minimal, with Hicks’ grunts and radio barks feeling authentic but wooden. Ambient effects, like echoing drips in ruins or humming force fields, build paranoia, contributing to an experience that’s viscerally tense. Though not revolutionary, these elements synergize to make CodeRED feel alive, turning technical limits into atmospheric strengths.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its January 2003 launch, CodeRED: Battle for Earth garnered strong critical acclaim in niche circles, averaging 90% from four reviews on MobyGames. GameHippo.com hailed it a “perfect 10/10,” praising its polish and value as freeware that “outshines many paid titles.” Czech outlets like FreeHry.cz (91%) and Freegame.cz (88%) lauded the Quake II upgrades and lengthy campaign, calling it a “delicacy” for budget gamers, while Hrej! (80%) noted graphical excellence despite familiar mechanics. Commercially, as a free download via Planet Arena, it achieved modest success—downloaded thousands of times, per abandonware logs—but lacked mainstream exposure, overshadowed by Return to Castle Wolfenstein.

Player reception was mixed: a 3/5 average from two MobyGames ratings reflected frustrations with difficulty spikes and first-mission opacity (one user quipped, “I never know what to do there”). No Metacritic aggregate emerged, underscoring its obscurity. Over time, reputation evolved positively in retro communities; sites like MyAbandonware rate it 5/5 from two votes, with users sharing compatibility tips for XP-era hardware (e.g., running on Athlon 64 with GeForce 8800GT). Ports to Linux and FreeBSD broadened access, cementing its open-source ethos.

Legacy-wise, CodeRED influenced the indie FPS wave, inspiring COR’s sequel CodeRED: The Martian Chronicles (2003) and evolving into Alien Arena series, which adopted similar engine tweaks for community mods. It exemplified freeware’s role in democratizing gaming, paving the way for titles like Cube 2: Sauerbraten by showcasing Quake engine longevity. In the broader industry, it highlighted modders’ potential—Kirby’s work foreshadowed Source engine mods and free-to-play shooters. Today, preserved on abandonware sites, it endures as a historical artifact of early 2000s indie resilience, influencing discussions on game preservation amid engine obsolescence.

Conclusion

CodeRED: Battle for Earth masterfully weaves Quake II’s foundations into a compelling tapestry of alien dread, mechanical betrayal, and heroic defiance, its freeware status belying a depth that rivals contemporaries. From its conspiracy-laden narrative and refined mechanics to evocative world-building and fervent reception, it captures the era’s innovative spark. Flaws like repetition and technical quirks aside, its legacy as a beacon for indie creators secures its place in video game history—not as a blockbuster, but as an essential underdog that proved passion trumps polish. Verdict: A must-play for FPS historians; download it today and join Hicks’ fight—8.5/10.