- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ak tronic Software & Services GmbH

- Developer: Phenomedia AG

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Automobile, Track racing, Vehicle simulator, Vehicular

- Setting: Canyon, Desert, Ice, Outdoor, Volcano

Description

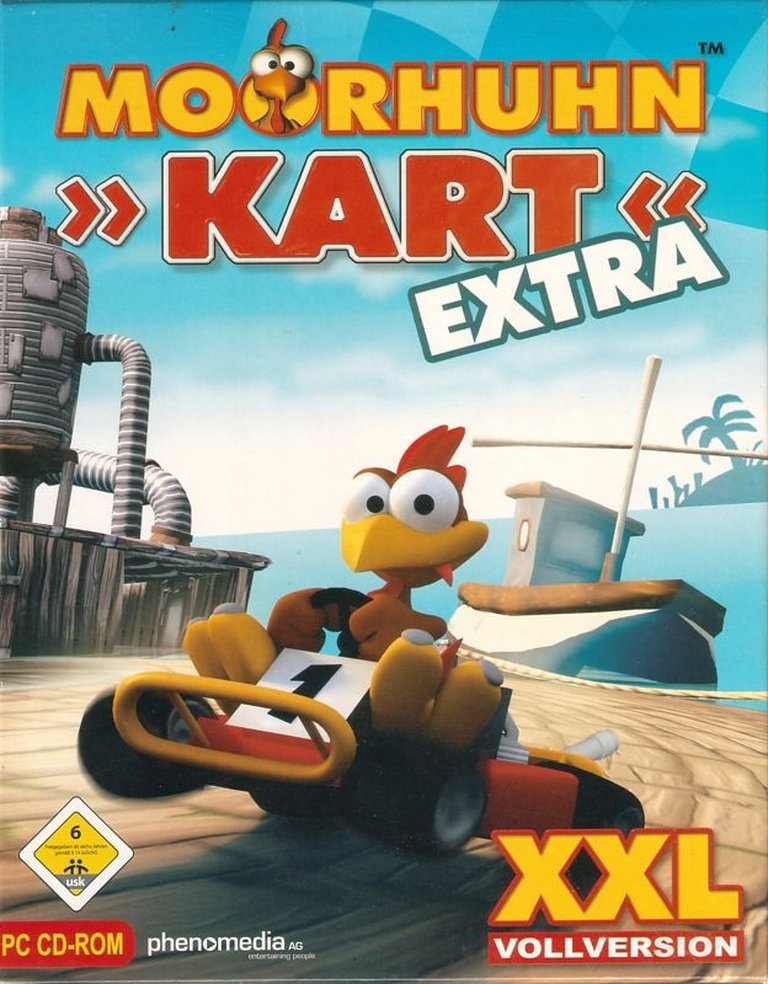

Crazy Chicken: Kart Extra is the graphically enhanced sequel to Moorhuhn Kart, featuring kart racing with five selectable characters from the Moorhuhn family, such as the titular chicken and other whimsical figures. Players compete across 10 varied racetracks—including desert, ice, and volcano themes—using power-ups like lightning strikes and oil slicks to sabotage opponents in modes like Grand-Prix, time trials, and two-player races, all in arcade-style driving action.

Crazy Chicken: Kart Extra Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : Crazy Chicken: Kart Extra delivers the same pick-up-and-play racing action that fans loved in Moorhuhn Kart, but with a few extra bells and whistles.

Crazy Chicken: Kart Extra: A Schleichweg Through Gaming History

Introduction: The Chicken Crosses the Finish Line (Eventually)

In the early 2000s, a peculiar viral phenomenon hatched in Germany: a simple shooting gallery game featuring hapless, animated chickens. The Crazy Chicken (or Moorhuhn) franchise became a cultural touchstone, a pre-smartphone era casual gaming juggernaut that boarded millions of office PCs and sparked national debates about productivity and “Killerspielen.” From this unlikely foundation sprang a bewildering array of spin-offs, one of which was Crazy Chicken: Kart Extra (2003), the first significant expansion of the franchise’s answer to Mario Kart. This review argues that Kart Extra is not merely a budget-cloned kart racer but a fascinating, if flawed, artifact of a specific moment in gaming history. It embodies the Pragmatic Expansionism of a studio riding a viral wave, the technological constraints of early-2000s PC development, and the inherent challenges of translating a beloved, simple IP into a more complex genre. Its legacy is one of competent, derivative fun that perfectly served its core German audience but ultimately revealed the creative and commercial limits of a franchise built on a single, brilliant, and increasingly exhausted core loop.

Development History & Context: From Advergame to Empire, Then to the Racetrack

The story of Crazy Chicken: Kart Extra cannot be separated from the bizarre, meteoric rise and subsequent turmoil of its parent franchise and developer. The original Moorhuhn was born not from a creative vision for a game, but as a 1998 advergame for Johnnie Walker whisky, developed by the Dutch studio Witan Studios for the German Art Department agency. Its illicit release and subsequent viral download frenzy in 1999-2000 transformed it from a marketing stunt into Germany’s most downloaded game, a “Büro-Phänomen” (office phenomenon) so pervasive it allegedly cost German industry hundreds of millions in lost productivity.

This success birthed Phenomedia AG, the company that commercialized the IP. By the time Kart Extra entered development, Phenomedia was a powerhouse of casual gaming, but one perched on a rickety foundation. The studio was already feeling the after-shocks of the dot-com bubble burst and was embroiled in the scandal that would see its top executives jailed for securities fraud in 2002-2003. Kart Extra, developed by Phenomedia AG and published by the ubiquitous ak tronic Software & Services GmbH, was thus a product of a company in apparent commercial success but underlying financial and legal chaos.

Technologically, the game was a product of the early-PowerPC/early-DirectX era. The original Crazy Chicken Kart Classic (2002) had already established the template: a 3D kart racer using what sources suggest was likely a customized or licensed middleware engine (common for the era’s budget titles) to render simple tracks and vehicles. Kart Extra was an “expansion” in the most literal sense—it added five new tracks to the original five, a remixed main theme, and “different physics for the different playable drivers.” This incremental approach was a hallmark of Phenomedia’s output: rapid, low-cost iterations focused on quantity and brand saturation over groundbreaking innovation. The gaming landscape of 2003 was dominated by the juggernaut that was Mario Kart: Double Dash!! on the GameCube. Kart Extra’s existence is a direct, if unambitious, response to that success, attempting to carve out a niche in the German-speaking budget PC market with a recognizable, home-grown IP.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Grand Prix of Nothing

As a kart racer, Crazy Chicken: Kart Extra possesses a narrative depth commensurate with its genre: effectively zero. There is no plot, no cutscenes, no in-race dialogue or story mode. The “narrative” is entirely implicit and environmental: the player selects one of five characters from the “Moorhuhn-Family” (the iconic Crazy Chicken itself, the amphibious Moorfrosch, a Snowman, the dim Lesshuhn, and a Pumpkinhead) and competes against the other four on a series of wildly themed tracks.

The themes are pure, unadulterated arcade chaos and friendly competition. The thematic through-line is the franchise’s core identity: humorous, slightly surreal, and family-friendly mayhem. The tracks themselves—with names like Kritzelklotz (Scribble Block), Docklands, Boooh!, Wüste (Desert), Canyon, Eis (Ice), and Vulkan (Volcano)—paint a picture of a vague, theme-park-like world where these avian and other odd characters race. It’s a world built for gameplay diversity (different surfaces, hazards) rather than lore. The “thematic deep dive,” therefore, is a dive into the void. Its power is in its absolute lack of pretense, a pure mechanics-first design that would have been familiar to anyone who’d ever played a kart game. Any deeper meaning—a satire of consumerism, a meta-commentary on the franchise’s own repetitive nature—is entirely absent, which for this type of game, is both a strength and a critical weakness.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Grand-Prix Grind

Kart Extra’s gameplay is a direct, unmodified lift of the Mario Kart blueprint, for better and for worse.

Core Loop & Racing: The fundamental experience is behind-the-view kart racing on the ten included tracks. Handling is arcade-style: slidey, forgiving, and reliant on the “karts” having distinct (if rudimentary) physics as per the developers’ claim. The objective is simple: finish in the top positions to earn points in the Grand Prix mode. The tracks are static courses with no dynamic obstacles or evolving layouts, a stark contrast to later entries in the series like Kart 3 or Thunder which would add more interactive elements.

Power-Ups & Weapons: Players collect random power-up boxes (the genre staple) containing items to “make the player’s life miserable, such as lightning strikes, steamhammers and layers of oil.” The critical flaw, noted by critics, is that these items are used by all AI opponents, who are programmed with a single-minded objective: “to keep the player from winning no matter what.” This creates a famously brutal, “rubber-banding” AI difficulty. In a Grand Prix race, being in first place means being pelted with every offensive item in the game, while the AI behind you might be driving unimpeded. This design choice prioritizes chaotic frustration over balanced competition, a hallmark of early, cheaply-made kart clones.

Game Modes: The three modes are barebones:

1. Time Race: A single-lap or full-race trial against the clock. A standard, low-stakes option.

2. 2-Player Split-Screen: The lone multiplayer offering. For its time, local splitscreen on a PC was a notable feature, though the graphical demands would have taxed many systems.

3. Grand-Prix: The primary single-player mode. The player must race through several tracks, qualifying for the next by achieving a high enough position. The critical, and deeply flawed, rule: “If you are too slow, the Grand-Prix is over.” This is a punishing elimination mechanic. A single bad race due to item spam or a mistake doesn’t just lose you points; it ends your entire championship run. This design is brutally unforgiving and heavily incentivizes save-scumming or repeated attempts, fundamentally undermining the fun, casual spirit the genre should embody.

Character Progression & UI: There is no character progression, kart customization, or unlockable content beyond simply accessing the Grand Prix. The UI is functional, displaying position, lap, item inventory, and a minimap—all standard for the era. The innovation, if it can be called that, is the differentiated driver physics, though without a stat screen or clear feedback, this is largely imperceptible to the player.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A charming, static diorama

The Crazy Chicken universe has always been one of charming, low-poly, cartoonish absurdity. Kart Extra’s tracks exist in this same aesthetic universe. They are not expansive 3D worlds but static, polygonal courses set against bright, simple skyscapes or environments. The Luna track is a low-gravity moon base; Vulkan is a winding road around a lava-filled crater. The world-building is entirely through visual theme and track naming, with no cohesive geography. It feels less like a racing league in a world and more like a series of disconnected theme park rides.

The art direction is the game’s strongest suit, as noted by the critic from Hrej! (“Grafika je chvályhodná” – The graphics are praiseworthy). For a 2003 budget title, the character models are colorful and expressive, the tracks are clearly delineated with bold colors, and the overall look is clean if undetailed. However, as the PlnéHry.cz critic astutely observed, this graphical style was already “tradiční” (traditional) and offered “praktisch keine Veränderung” (practically no change) compared to its immediate predecessors. It was competent, dated-looking even at release, but functionally clear—a crucial requirement for a racer where track borders and hazard placement must be instantly readable.

The sound design follows a similar pattern. The remixed main theme is serviceable, energetic, and loopable. Sound effects for item usage, collisions, and engine noise are standard arcade fare. The composer credit for the broader franchise points to Nils Fritze for earlier soundtracks, but Kart Extra‘s audio is generic and functional, lacking the memorable punch of, say, the Mario Kart series. It does its job without ever distinguishing itself.

Reception & Legacy: A Niche Success, a Critical Afterthought

Crazy Chicken: Kart Extra‘s reception was, and remains, firmly in the ” mediocre” bracket. The aggregated critic score of 62% tells the story. Reviews were mixed, praising the competent, cheerful graphics but uniformly panning the lack of content and derivative design.

- Critic Consensus: The Hrej! review (7/10) called it a “slušná” (decent) game but noted its “absence of tracks and various game modes” compared to previous titles, which “schází” (diminishes) it. PlnéHry.cz (6/10) explicitly stated they preferred Moorhuhn Kart 2 “both gameplay-wise and graphically,” finding Extra to offer “uboze málo” (pitifully little). Absolute Games (55/100) delivered the most damning verdict: the game would finish “maximálně za půl hodiny” (in half an hour at most) and only held appeal for children under 10-11. This last point is crucial: the game was explicitly targeted at and appreciated by a very young, casual audience, not critical sensibilities.

Commercial & Cultural Legacy: Within its core German market, Kart Extra was a commercial success as part of the broader Moorhuhn machine. It was included in multiple budget compilations (Moorhuhn Total 2 (2005), Moorhuhn: Die Ersten 10 Jahre (2009), Moorhuhn Total 4 (2007), Moorhuhn Complete (2016)), proof of its steady, if unspectacular, sales. However, it represents the beginning of the franchise’s stagnation in this genre. Later entries (Kart 2, Kart 3, Thunder) would iterate with more tracks, online play, and customization, but the core criticism—that these were inferior, less polished imitations of Nintendo’s gold standard—persisted. The Crazy Chicken Kart series never achieved the cultural penetration of the mainline shooters and is often cited as a primary example of the franchise’s “monotony” and cash-cow exploitation.

Its place in video game history is as a case study in regional, budget-conscious franchise extension. It demonstrates how a company used a potent local IP to enter a popular genre with the bare minimum of development, banking on brand loyalty alone. Internationally, it was virtually invisible, a “shovelware” title on Steam and discount bins, highlighting the insurmountable cultural barrier the Moorhuhn franchise faced outside German-speaking Europe. It is a footnote in the history of kart racers, but a significant one in the history of German casual gaming’s attempt to diversify.

Conclusion: A Racer for the Stuck-in-Traffic Gamer

Crazy Chicken: Kart Extra is a game perfectly of its time and place. It is the logical, if uninspired, extension of a phenomenon: taking a wildly popular, simple IP and applying it to the era’s most popular casual genre. Its strengths are its cheerful, functional aesthetics and its pure, unambiguous arcade sensibility. Its weaknesses are its profound lack of ambition, its punishing AI, its shockingly thin content package, and its total failure to capture the whimsical, polished magic of the titles it so clearly imitates.

As a historian, its value lies not in its quality but in its ordinariness. It is the engine room of the Moorhuhn empire—a workaday product churned out to satisfy demand, representing the point where the franchise’s creative well began to run dry and its strategy shifted to pure, iterative, compilation-ready output. For the German child of 2003, it was likely a delightful, familiar romp. For the historian, it is a clear indicator of a studio managing a viral asset through its commercial peak and into its long, tail-wagging decline. It is not a lost classic. It is not an insult to gaming. It is, simply and definitively, Moorhuhn on wheels—flawed, functional, and irrevocably tied to a specific cultural moment when the most important thing was not innovation, but getting another product with the chicken on it onto the shelf.

Final Verdict: 5/10 — A competent but creatively bankrupt kart racer that serves primarily as a historical artifact of the Moorhuhn franchise’s mass-market, budget-game phase. Essential only for completists and cultural historians of early-2000s German casual gaming.