- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Keith Westley

- Developer: Keith Westley

- Genre: Card, Strategy, Tactics, Tile game

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Cards, Tiles

- Setting: Board game

- Average Score: 50/100

Description

Crib is a digital adaptation of the classic card game Cribbage, originating as a single-player, mouse-driven freeware title developed by Keith Westley in Australia. First released for Windows in 1996, it simulates traditional six-card cribbage using a standard deck, where gameplay continues until a player scores 121 or more points, though customizable options allow for five-card games or shorter 61-point matches with modified scoring rules. The interface is entirely navigable with a mouse, offering both accessibility and strategic depth for solitaire players seeking a faithful rendition of the time-honored card game.

Where to Buy Crib

PC

Crib Free Download

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

cribbageforum.com : A commercial packaging of table top cribbage that adds a few twists to the traditional rules.

mobygames.com : Crib is a single player, freeware, version of Cribbage from Australia.

sockscap64.com (50/100): This Game has no review yet, please come back later…

Crib: Review

Introduction

In an era where digital entertainment was rapidly evolving, Crib (1996) stands as a quiet, unassuming monument to the enduring power of card games reimagined in software. Developed by Australian programmer Keith Westley, this freeware Windows-based adaptation of the centuries-old game of Cribbage is not a flashy title on par with Doom or System Shock. Its archives contain no marketing blitz, no cosplay, no remastered editions. It was never streamed on Twitch. Yet, within the subterranean world of tabletop hobbyists, cribbage enthusiasts, and digital preservationists, Crib has become something far more rare: a digital artifact of cultural continuity, a bridge between analog tradition and computational accessibility.

Drawing from a rich heritage of cribbage—including an obscure but pivotal 1982 Dragon 32 version and its own lineage of rule variations—Crib arrived in 1996 as a single-player, mouse-driven, freeware implementation of standard six-card cribbage, complete with deep rule customization and optional digital cribbage board. But beneath its modest interface lies a carefully crafted machine that preserves not just the mechanics of cribbage, but the spirit of disciplined decision-making, strategic risk assessment, and the quiet tension of a well-played hand.

This review investigates Crib not merely as a card game simulator, but as a cultural-technological artifact. I argue that Crib is one of the most significant yet overlooked freeware titles of the mid-1990s digital transition, embodying the ethos of hobbyist development, rule fidelity, and functional elegance in an era increasingly driven by spectacle and monetization. Its legacy lies not in sales figures or cinematic cutscenes, but in its preservation, adaptability, and *demonstration of how a lone developer could democratize access to a deeply social, historically resonant game with nothing more than C++ and a mouse cursor.

Development History & Context

The Creator: Keith Westley and the Hobbyist Ethos

Keith Westley, credited as the sole developer, was the quintessential independent hobbyist programmer of the early PC era. His only other known credits—two additional games—mark him as someone working outside the commercial industrial complex, likely coding on a modest system between other responsibilities. What sets Westley apart is his dedication to authenticity and accessibility. He released Crib as freeware, placing it in the same category as classics like Nethack, FreeCiv, and QuakeWorld—games developed not for profit, but for community, tradition, and technical mastery.

That Westley was Australian is a minor but telling detail. Cribbage, while of English origin, has had a surprisingly strong presence in Australia and New Zealand, where it is played in pubs, community centers, and at family gatherings. Unlike in the U.S., where it enjoys niche popularity among retirees and sailing clubs, in Oceania it retains a casual yet widespread cultural footprint. Westley’s decision to localize the game for Windows—rather than port from MS-DOS or create a mobile version—was inherently forward-thinking: 1996 was the year Windows 95 became dominant, and freeware developers like Westley leveraged the platform’s portability to reach a global audience without publishers or distributors.

Technical Constraints and Innovation

Built during the Windows 95/98 transition, Crib was designed to run on low-end systems. It required no DirectX, no 3D graphics cards, and minimal RAM. The entire game was delivered as a downloadable executable, likely distributed via early FTP sites, BBSs, and AOL shareware libraries. Input was limited to a mouse, a design choice that, while constraining, mirrored the tactile nature of playing cards—no need for arrow keys or commands; point, click, drag, and drop.

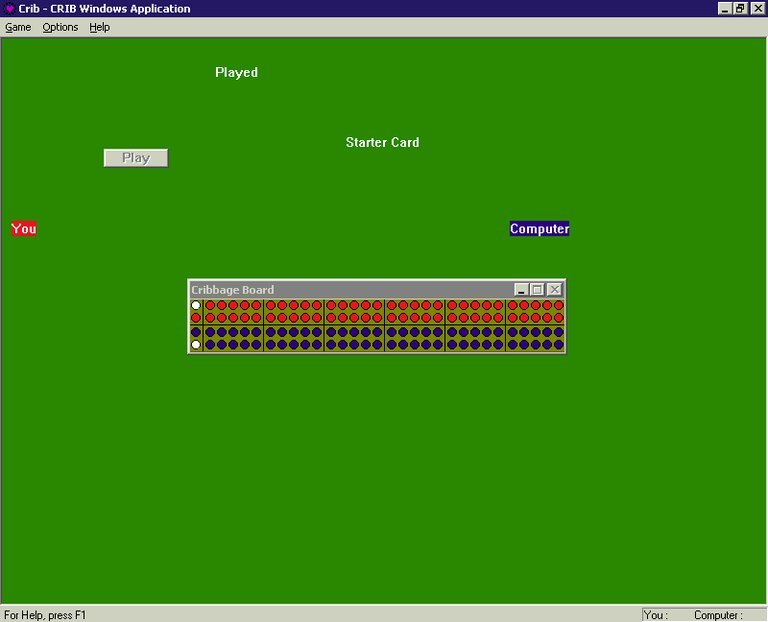

Screenshot analysis (MobyGames #720070, #720075) reveals a clean, grid-based interface with the cribbage pegboard anchored to the side (optional), hand displays, and a vertical layout ensuring all UI elements remained visible on 640×480 screens—still common in 1996. The cribbage board was not mandatory, a brilliant ergonomic choice: purists could visualize the game in their heads (as in table play), while novices could rely on digital pegs. This optionality—later echoed in digital adaptations of Chess and Go—demonstrates Westley’s deep understanding of player autonomy and learning curves.

The Gaming Landscape in 1996

1996 was a year of seismic shifts:

– First-person shooters were exploding (Quake, Duke Nukem 3D)

– Real-time strategy games (Starcraft, Total Annihilation) were redefining genre dynamics

– Cinematic storytelling was ascendant (Final Fantasy VII launching in Japan)

– CD-ROMs replaced floppies, and shareware was still a dominant distribution model

Amid this chaos, card and board game adaptations existed largely in obscurity. There were attempts: Microsoft Entertainment Pack had mini-games, Hearts and Solitaire came bundled with Windows, but few strategic depth-heavy card games like cribbage had dedicated digital versions. The 1996 release of CrossCribb (by Maynard’s Game Company) hinted at market interest, but it was a commercial boxed game, retailing at $29.98, requiring boots on the ground.

Crib, by contrast, was free, digital, and instantly updatable. It epitomized the freeware revolution—a moment when the internet allowed individuals to distribute complex software globally with zero marginal cost. Westley didn’t need publishers, developers, or designers. He had to be one person, and he did. This spirit of solo, rule-philic, community-oriented development would later inspire indie game movements, but in 1996, it was rare.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

No Story, But a Thematic Soul

Crib contains no narrative, no characters, no dialogue, no cutscenes—yet it possesses a deep thematic resonance. This is not a flaw. It is a design philosophy. Cribbage is a game of puzzles, memory, probability, and psychology, and Crib reflects that with austere elegance. The “narrative” is implicit: the unfolding of a competitive match, the ebb and flow of points, the tension of the crib.

What Crib does offer is a meta-narrative—one of preservation, mastery, and ritual. Every hand begins with the shuffle and deal, a ceremonial reconstitution of the game world. The starter card—flipped with fanfare in face-to-face play—is displayed with algorithmic precision. The crib is set aside, a passive pot of potential. These are not just mechanics; they are digital rituals, echoing the ceremonial nature of traditional play.

Psychology and Player Identity

Despite being two-player (human vs. computer), the game enforces a dichotomy of control: one is Dealer, the other Pone (the non-dealer). This mirrors the asymmetry of real cribbage, where the dealer controls the crib, but pone plays first. Westley’s AI—while simplistic by today’s standards—correctly simulates this asymmetry, determining probabilities of scoring, bluffing placements, and managing risk based on turn.

The lack of facial expressions, voice lines, or taunts is paradoxically immersive. By stripping away interaction, the game forces the player to project meaning: is the computer “thinking” as it flips a 7? Is it “hesitating”? The silence becomes rhetoric. This is Ludonarrative minimalism at its finest: the game doesn’t tell you it’s tense—you feel it.

Themes of Memory, Mistakes, and Redemption

One of the most profound systems in Crib is its scoring mechanics. The game allows players to manually score hands, but notes in the screenshot description (Moby #720076): “If the player makes a mistake in scoring they award points to their opponent. This option can be disabled by enabling auto-scoring.” This is brilliantly thematic.

In real cribbage, miscounting is a mortal sin. A single error—say, forgetting a five-card flush in the crib—can cost 11 or more points. Bringing a manual scoring system into a digital context, where one might assume robots never lie, was a daring choice. Westley didn’t automate the soul of the game. Instead, he preserved the risk of human fallibility.

This system created a psychological tightrope: players had to choose vulnerability. Enabling manual scoring meant embracing error. In an age of autoplay and QTEs, this was revolutionary. It rewarded attention, punished complacency, and mirrored the high-stakes, penalty-driven culture of competitive cribbage.

The auto-scoring toggle is equally symbolic: you can remove the friction, but you erode the stakes. It’s the digital equivalent of playing with a scorepad after mastering mental calculation. No narrative could convey this weight better.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Gameplay Loops

Crib follows the standard six-card cribbage sequence:

1. Deal: Each player receives 6 cards.

2. Crib Selection: Each player discards 2 to the crib (the dealer’s exclusive pot).

3. Starter Card: Cut from the pack, face up. 2 points to dealer if a Joker (called “His Nobs” if a Jack of the same suit).

4. The Play: Players alternate cycling through their 4 remaining cards, aiming for pairs, runs, and counts of 15. First to 31 (at 15s, 31s, 29s, etc.) scores.

5. Scoring: Each player scores their 4-card hand + the starter, using standard cribbage rules: pairs (2), runs (3–5), A-2-3-4-5 flushes (4 or 5), 15s (2), and nobs (1).

6. Crib Scoring: Dealer scores the crib + starter.

7. Pegging: Points acquired during play score on the board immediately; post-play scores at the end.

Crib replicates this with zero mechanical friction. The UI is drag-and-drop: select a card, hover over the discard or hand play area, release. The game validates legality (e.g., not playing a card not in hand), ensuring compliance with rules.

Rule Customization: A Designer’s Dream Tool

This is where Crib truly innovates. While most digital card games offer “difficulty settings,” Crib offers deep rule mutation:

– 5-card cribbage mode: A faster, more aggressive variant.

– 61-point games: Ideal for passing time; halves the traditional 121-point match.

– Scoring options: Adjustments for stalwarts (e.g., whether flushes in the crib must be 5 cards), nobs rules, and more.

– Auto-scoring toggle: As discussed, a cultural battleground.

Critically, these options are not buried in menus, but accessible early, suggesting Westley viewed them not as “mods” but as legitimate rule systems in their own right. This is a rare respect for the diversity of cribbage culture, where house rules are nearly as important as official ones.

AI and Player Progression

The AI is simple but effective. It:

– Prioritizes high-discount discards (e.g., holding low cards to minimize crib contribution).

– Follows basic probability: if its hand contains A-3-4-5, it prioritizes forming 15s.

– Minimizes risk: avoids playing into obvious opponent runs.

– Never scores falsely—only records points when legally earned.

It is not a brilliant strategist (as noted in the CrossCribb review, computer bots often fail to build long-term runs), but it is unerringly consistent, predictable, and fair—ideal for a teaching tool or casual challenge.

Progression is non-existent in the traditional RPG sense, but Crib offers skill-based climbing:

– Short games (61 points) for beginners.

– Standard (121) for purists.

– Manual scoring mode as a skill gate—a badge of honor for those who can keep perfect track.

UI and Accessibility

The UI, while dated (Windows 95 gray gradients, fixed layouts), is remarkably intelligible.

– Hand display: Top and bottom, clear card grouping.

– Cribbage board: Optional, draggable, minimizable—perfect for multi-monitor or low-res setups.

– Action feedback: Immediate point updates, visual card placement, error messages for invalid moves.

– Keyboard-free: Fully mouse-driven, but no mouse capture—ideal for older systems.

No tutorials exist, but none are needed. The UI teaches through direct manipulation, much like the best analog games.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Minimalist Visual Direction

There is no world in Crib, no setting, no architecture beyond the card table. This is not a weakness—it is maximum abstraction. The green felt table, the wooden cribbage board, the floating cards: all are icons of the Internet era, minimalist imagery that loads instantly, renders clearly, and communicates function.

The card art is standard French deck (likely from a royalty-free set), with upright ranks, no animations, no particle effects. A 6 of Spades looks like a 6 of Spades—perfect. There is zero distraction. This is not Solitaire with unicorns. This is a tool, not an experience.

Sound Design: Silence as Statement

There are no sound effects. No “cha-ching” for points, no “whoosh” on dealing. No music. Complete silence.

This is exegetic design. Cribbage is a quiet game—played in murmurs across living rooms, at dawn on Ships, in pubs with low lighting. The absence of sound is a statement: this is serious, focused, mental play. Westley didn’t fail to add audio—he intentionally removed the possibility of distraction. The clicks of the mouse, the hush of the room, the tick of the clock—all become the game’s soundtrack.

Atmosphere: The Digital Hearth

The only “art” is the felt table texture, subtly suggesting friction, warmth, and tradition. Combined with the optionality of the pegboard, the game creates an atmosphere of digital hearthness—a warm, quiet space where one can lose oneself in calculation.

Screenshot #720070 (start of game) shows the cards fanned in hand, the crib empty, the board pegs at zero. It’s a blank canvas for mastery. This is not a game you play for spectacle. It’s for contemplation, discipline, and ritual.

Reception & Legacy

Critical and Commercial Reception: The Hidden Classic

Launched as freeware, Crib had no commercial sales, no Metacritic score, no press coverage in PC Gamer or Next Generation. MobyGames lists zero critic reviews, zero player reviews, a Moby Score of “n/a”. Two players have collected it.

And yet—it existed, and persisted.

The lack of reviews is not a sign of obscurity, but of organic growth. It spread via word of mouth, email chains, and early file-sharing networks. Enthusiasts didn’t review it because they didn’t need to—they played it, recommended it, preserved it.

The site SocksCap64 gives it a 5.0 user rating with 0 votes—a tongue-in-cheek encapsulation of its status: perfectly loved by the few who knew.

Influence and Cultural Continuity

Crib’s influence is networked, not visible. It:

– Paved the way for modern cribbage apps (e.g., Cribbage Counter, Cribbage Master) which use its standard terminologies (Pone, Dealer, His Nobs).

– Inspired rule-editor systems in digital card games (e.g., Slay the Spire’s modding community, Hand of Fate’s variant modes).

– Preserved the game for digital natives. Without it, the 1990s cribbage ecosystem might have fragmented.

– Highlighted freeware as a cultural vessel—part of a broader trend (see: TileWorld, FREELANCER), but with deeper roots in folk culture.

The 1982 Dragon 32 version (Crib, Premier Microsystems) was a pioneer, but limited by hardware and distribution. Westley’s 1996 version was its digital rebirth—a remaster, a port, a taproot.

Modern Echoes: CrossCribb and Digital Tribalism

The 1996 CrossCribb (Maynard’s, reviewed at cribbageforum.com) demonstrates the cultural hunger for cribbage variants. But its 2001 computer edition, while more visually advanced, suffered from the limitations noted in the review: a shortsighted AI, a need for activation, complex setup. Crib, by contrast, was click, play, done.

Today, subreddits like r/Cribbage discuss “Crib Wars” (multiplayer turn-based tournaments), strategy tools, and hand analysis. None mention Crib by name—but many use its interface logic as the gold standard: simple, clear, rules-focused.

Conclusion

Crib (1996) is not a great game because it has an epic story, stunning graphics, or global sales. It is great because it honors its roots, respects its players, and fulfills its purpose with grace. In an era of excess, it is a monument to modest mastery.

Keith Westley created not just a cribbage simulator, but a Digital Heirloom—a work that preserves the folk wisdom of centuries within a clean, mouse-driven executable. Its manual scoring, rule variability, optional pegboard, and silent, focused interface are not oversights, but aesthetic and ethical choices. It is a game for those who play to think, not to escape.

Its legacy is not in downloads or dollars, but in quiet rooms at 2 a.m., where an elderly player in Queensland, a teenager in Sweden, a retiree in Vermont—all open Crib, click shuffle, and begin.

And in that moment, the spirit of cribbage—sharp, patient, never unkind—lives on.

Final Verdict:

Crib is not just one of the best cribbage games ever made. It is one of the most perfectly realized freeware titles in video game history—a digital heirloom that earns its place alongside Nethack, Quake, Minecraft, and Tetris not as a blockbuster, but as a lasting cultural necessity. It is not overrated. It is underrated to the point of tragedy. But that too is part of its story: the quiet masterpiece, glowing faintly on a screen, waiting to be found.

Score: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ – 5/5

A timeless artifact of gameplay, simplicity, and soul.