- Release Year: 2006

- Platforms: PlayStation 2, Windows

- Publisher: Akella, Ubisoft Entertainment SA

- Developer: Telltale, Inc.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Puzzle elements

- Setting: City, Las Vegas

- Average Score: 71/100

Description

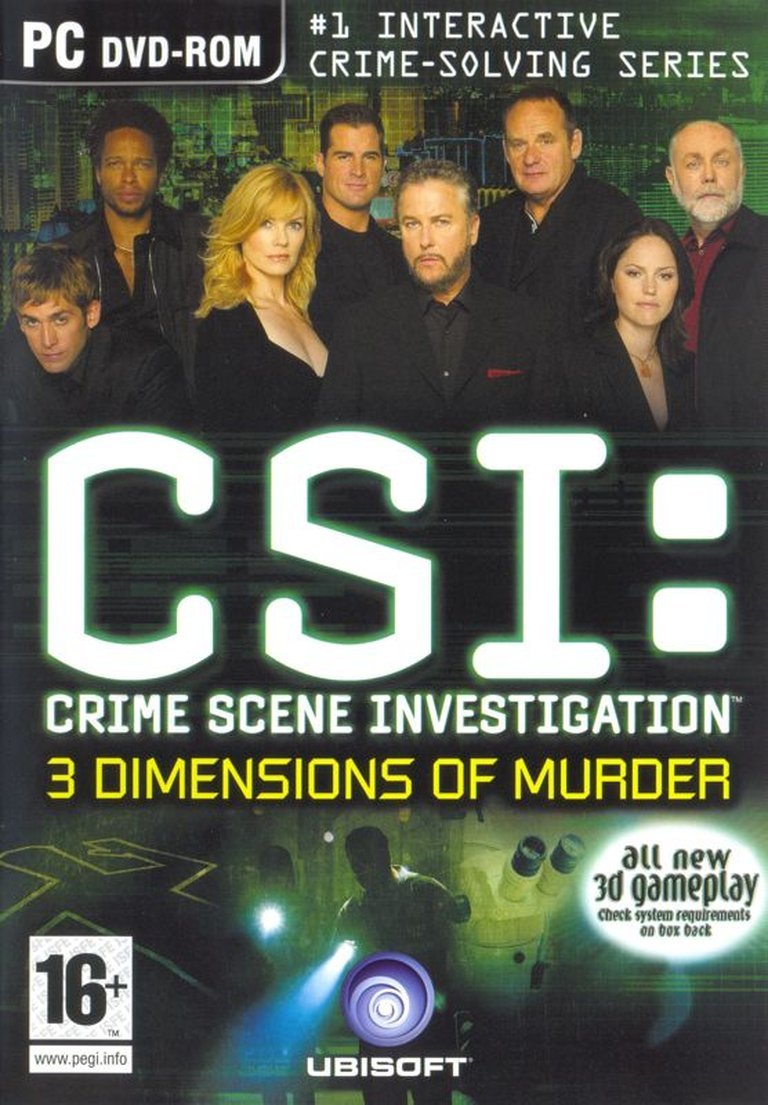

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation – 3 Dimensions of Murder is a point-and-click adventure game where you play as a rookie investigator in the Las Vegas crime lab, solving five interconnected murder cases that build toward a final resolution. Set in a fully 3D environment that allows you to manipulate evidence and explore scenes, the game features voice acting from the original TV series cast, three difficulty levels that adjust in-game hints, and a performance rating system from Gil Grissom based on your evidence collection and analysis.

Gameplay Videos

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation – 3 Dimensions of Murder Free Download

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation – 3 Dimensions of Murder Patches & Updates

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation – 3 Dimensions of Murder Guides & Walkthroughs

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation – 3 Dimensions of Murder Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (67/100): It’s very good at what it’s doing, but the problem is that’s very limited.

gamesreviews2010.com (75/100): For fans of the CSI TV series and crime-solving games in general, CSI: 3 Dimensions of Murder is an absolute must-play.

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation – 3 Dimensions of Murder: A Shy Step into the Third Dimension

Introduction: The Weight of the Badge, the allure of the 3D Model

In the mid-2000s, the CSI: Crime Scene Investigation television franchise was a global cultural juggernaut, its formula of grisly murders solved by a quip-prone, hyper-competent team of Las Vegas forensic specialists captivating audiences. Translating that success to the interactive medium was a logical, if perilous, venture. By 2006, Ubisoft’s partnership with developer 369 Interactive had already produced two titles, CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (2003) and CSI: Miami (2004), establishing a solid, if formulaic, point-and-click adventure template. The announcement that the nascent Telltale Games—a studio fresh from the Bones series and still years away from its narrative revolution with The Walking Dead—would take the reins for the third mainline entry, CSI: 3 Dimensions of Murder, signaled a potential turning point. Its very title promised a technological leap: full 3D graphics. This review argues that 3 Dimensions of Murder represents a crucial, yet fundamentally conservative, evolutionary step for the CSI game series. It successfully modernizes the franchise’s presentation and streamlines certain forensic mechanics, fulfilling the promise of its title’s namesake, but it remains shackled to the series’ core, increasingly restrictive design dogma. It is a game that looks to the future whileaping its feet in the well-worn, linear trenches of its licensed past, making it a fascinating case study in incremental innovation versus transformative design.

Development History & Context: Telltale’s First Forensic Leap

The development history of 3 Dimensions of Murder is defined by a changing of the guard. After two games, Ubisoft shifted the CSI license from 369 Interactive to Telltale Games, a studio co-founded by veterans of LucasArts who had recently wrapped work on Bone: Out from Boneville. This transition is the single most significant factor in the game’s identity. Telltale, known for its character-driven storytelling and episodic structure (even in 2006), approached the CSI formula not with a desire to radically overhaul it, but to “improve upon the groundwork laid by the three previous games,” as noted by Adventure Gamers. Their chief stated innovation was the move to a “new 3D engine,” a proprietary system likely an early iteration of what would become the Telltale Tool.

This technological shift occurred within the context of the mid-2000s PC gaming landscape. The adventure genre was in a lull between its late-90s golden age and its indie-driven renaissance. Meanwhile, the TV show was in the peak of its popularity (Season 6 aired during the game’s development). The constraint was stark: Telltale had to deliver a product that felt authentically “CSI” to fans while leveraging 3D to offer a more immersive, less static experience than the 2.5D pre-rendered backgrounds of its predecessors. The result was a game built on the Telltale Tool, which prioritized stylistic, toon-shaded visuals and efficient performance over cutting-edge polygon counts—a wise, if unambitious, choice given the genre’s typical audience and the need for clear, readable forensic scenes. The PS2 port, handled by Ubisoft Sofia in 2007, introduced significant complications; Sony America’s requirement for “free movement and control of the view” created “extraordinary difficulties,” according to Wikipedia, likely forcing a re-engineering of the camera and interaction systems on hardware far less capable than a contemporary PC. This port’s technical struggles are evident in its lower critical scores.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Five-Part Puzzle

The narrative structure of 3 Dimensions of Murder is the series’ most reliable and, paradoxically, its most tired element. It strictly adheres to the established formula: five self-contained cases, with the fifth serving as an over-arching “serial” plot that ties threads from the first four together. You play as an unnamed, silent rookie CSI, a avatar for the player, partnered with different members of the iconic Las Vegas lab team for each case.

Case 1: “Pictures at an Execution” introduces the player to the basics. A bride-to-be is bludgeoned with a hawk statue in an art gallery. Working with Warrick Brown, the suspects are a hot-headed fiancé, a gallery owner, and a reclusive artist. Thematically, it explores ego and artistic obsession, with the killer being the artist, Patrick Milton, driven to murder by the victim’s constant, cruel criticism of his portrait—a dark mirror to the creative process itself.

Case 2: “First Person Shooter” is a standout, a meta-textual in-joke that reveals Telltale’s voice. A video game CEO is murdered at a trade show. The suspects are industry archetypes: a gun-trained marketing exec, a betrayed roommate/employee, and a disgruntled former worker. The sharp, satirical dialogue, particularly from suspect Maya Nguyen (“everything Maya says about the industry and being a woman in it—absolutely true,” notes IGN), lampoons the volatility of game development and fan entitlement. It is widely cited by critics (IGN, Gamer 2.0) as a highlight, a case where the licensed product transcends its format to offer genuinely clever, insider commentary.

Case 3: “Daddy’s Girl” shifts to a casino heiress, Carrie Canelli, who fakes her death with her twin sister Lucy and a male nurse, Alex. The missing body and saturated crime scene create an initial puzzle. The theme is familial greed and sacrifice; Carrie rejects her father’s corrupt fortune, engineering her disappearance so Lucy can inherit it. The case’s twist relies on the body never being a murder victim at all, a subversion of the player’s expectations.

Case 4: “Rough Cut” is a more conventional triangle: a real estate developer’s son found dead in the desert. Poison, politics, and promiscuity are the motives. Working with Greg Sanders, the suspects are the victim’s wife, his socially climbing mother, and a seedy contractor. Thematically, it’s a tale of betrayal and hidden lives, but critics often found it the most “by-the-numbers” of the set, lacking the spark of Case 2 or the twist of Case 3.

Case 5: “The Big White Lie” is the connective tissue. A private investigator is found shot in an alley by Doc Robbins. The web of deceit involves blackmail and corruption, directly linking back to the art gallery owner (Nathan Ackerman) from Case 1 and the casino context from Case 3. Working with Grissom and Catherine Willows, it functions as the payoff, demanding the player synthesizes evidence from all previous investigations. The theme is systemic rot—the idea that crime is a tangled network, not isolated acts.

The overarching thematic through-line is less about profound philosophical inquiry and more about the methodology of truth-seeking. The game reinforces the CSI mantra: evidence doesn’t lie, people do. Each case is a lesson in following the physical trace from bloody scene to logical conclusion. The dialogue, written by Greg Land and Max Allan Collins, faithfully captures the show’s cadence: clinical, slightly arrogant, and punctuated by gratuitous puns (“Looks like we’ve got a handle on this situation,” remarks a CSI upon finding a broken statue). The voice acting, provided by the original cast (excepting a few, as noted in the credits), is consistently praised as “phenomenal” (IGN) and “superior,” the single greatest asset in establishing authenticity. However, the narrative itself is criticized for its predictability and lack of the show’s deeper character drama. As GameStar (Germany) bluntly states, it lacks the “dichten Charakterzeichnungen der Serie” (dense character drawings of the series).

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Forensic Repetition with a 3D Sheen

The core gameplay loop is the classic CSI adventure template, now filtered through a 3D space. The player navigates crime scenes and lab environments in first-person, clicking on “hotspots” to collect evidence (blood, fibers, fingerprints, hairs, etc.) using appropriate tools from a bottom-screen HUD banner. The infamous scrolling banner, decried by players as “annoying” and “frustrating” (vicrabb’s Moby review), remains a UI/UX failure, forcing tedious scrolling to select tools instead of a radial menu or hotkeys.

The shift to full 3D environments brought two primary mechanical changes, as highlighted in user and critic reviews:

1. Object Manipulation: Evidence items can now be rotated and examined from multiple angles on-screen. This is crucial for finding all latent fingerprints or hidden markings, adding a tactile, investigative layer absent in the 2D games. The user review correctly identifies this as a key improvement: “The 3D system does provide the ability to move evidence objects in different angles which helps to locate all available fingerprints.”

2. Lab Access & Freedom: A major pain point in previous games was handing evidence to a lab technician for analysis. 3 Dimensions largely rectifies this. The rookie is now “Greg is on the field now, so you can do what you want in the lab,” accessing the trace evidence computer, DNA analyzer, microscope, assembly table (from CSI: Miami), and chemical analysis computer directly. This “feeling of freedom” is a significant quality-of-life upgrade.

The forensic puzzles themselves are fundamentally unchanged in structure. They are puzzles of application and observation: using the right tool on the right object at the right time. DNA comparison, once a painstaking column-matching mini-game, is now simplified with colored strands, a much-appreciated accessibility tweak noted by the player review. However, the game’s greatest systemic flaw is its profound lack of failure states and meaningful consequences. As GameSpy‘s 50% review states succinctly: “The real downside to this is that you can’t fail. You’ll always uncover the real criminal, and you never have to worry about contaminating evidence.” Asking your partner for a hint only deducts points from your final “rookie/investigator/master” rating, but does not block progress. This complete lack of risk or challenge beyond pixel-hunting renders the detective work feel sterile and consequence-free. The rating system, meant to encourage thoroughness, feels hollow because, as the user review laments, “there is no bonuses in the game. Why reach the ultimate rank if you’re not rewarded?” This absence of unlockables or meaningful variation for mastery kills replay value, a point echoed by NowGamer (“it lacks any replay value”) and Cheat Code Central (“won’t have any lasting appeal”).

The three difficulty settings primarily toggle the “interactive help” systems: hotspot highlighting for navigation/tools, evidence tagging (showing when a location or item is fully processed), and the tool assist system. Turning these off increases the challenge but does not fundamentally alter the linear, solution-path design. The game remains a “lead-the-player” experience, as noted by the hardcore adventure critic, where the puzzle is not how to think, but where to click.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Sterile, Yet Faithful, Las Vegas

The transition to 3D was the game’s flagship selling point, and its execution is a classic “good for the time, dated now” story. Using the Telltale Tool, the game renders environments and characters in a clean, cel-shaded style. The Las Vegas crime lab is faithfully recreated, and locations like the art gallery, desert, and casino apartment are recognizable. Character models are “correct” and “recognizable,” as the player review states, capturing the likenesses of the actors. However, the visual identity is widely panned for being “sterilized,” “void,” and lacking atmosphere. Adventurearchiv complained of “zu dunklen, teilweise matschigen und unscharfen Locations” (too dark, partially mushy and blurry locations). The animation, particularly lip-sync, remains “rough, but passable” (IGN), a perennial weakness for Telltale until much later in their development cycle. The 2006 aesthetic simply couldn’t compete with the photorealism of mainstream AAA titles, and the artistic choice to prioritize readability over richness left the world feeling like a museum diorama of CSI rather than a lived-in space.

Sound design is a relative high point. The soundtrack consists of moody, atmospheric tracks typical of the show. The user review’s specific criticism—”sometimes, you have a blank…before music starting playing”—points to sloppy implementation, a jarring break in immersion. The true star is the voice acting. With the main cast (excepting a few, like perhaps Marg Helgenberger’s Catherine Willows, who is credited but whose participation is sometimes noted as reduced in later games) providing their voices, the game achieves an unparalleled level of authenticity for a licensed product. The writing, while serviceable, often feels like a first draft of a TV episode, but the performances sell it. The decision to have all text spoken, allowing subtitles to be turned off, was progressive for its time and aids immersion.

Reception & Legacy: Commercial Success, Critical Division, and a Shy Legacy

CSI: 3 Dimensions of Murder met with a mixed critical reception that solidified the series’ place as a competent but unremarkable licensed property. Aggregate scores hover in the high 60s on Metacritic/GameRankings (67/100 PC, 58/100 PS2). The PC version saw a notable split: IGN (86%), Adventure Lantern (85%), and Gamer 2.0 (79%) praised its engaging cases and improvements, while PC Gamer UK (55%) and Gamekult (50%) dismissed it as simplistic and unambitious. The PS2 port, due to its technical compromises and late arrival (over a year after the PC version), was panned (45% on GameSpot), a victim of poor timing and a botched conversion.

The commercial performance, however, was strong. By December 2006, combined global sales of 3 Dimensions of Murder and its two immediate predecessors (CSI: Dark Motives and the original CSI) reached roughly 2.4 million copies. This demonstrates the powerful draw of the CSI brand and the viability of the adventure game formula with a popular license. It proved there was a substantial market for these methodical, story-light, puzzle-medium experiences.

Its legacy is dualistic:

1. For the CSI Series: It is a clear, evolutionary improvement. The move to 3D, the increased lab freedom, and the streamlined evidence analysis (colored DNA, direct access) became the new baseline for subsequent titles like CSI: Hard Evidence (which, per Wikipedia and the PS2 version’s bonus case, reused the “Rich Mom, Poor Mom” scenario) and CSI: Deadly Intent. It validated Telltale’s approach, leading to them developing the next two main sequels. It was, as the user review concluded, a “shy start”—a new beginning that didn’t dramatically alter the core experience but polished its surface.

2. For Game Design: It represents a missed opportunity. In an era where narrative adventure games were struggling, 3 Dimensions of Murder doubled down on linear, puzzle-based progression with no meaningful stakes or branching. It offered no innovation to the genre beyond the licensed skin. Its legacy is not one of influence on other adventure games, but as a high-water mark (or low point, depending on perspective) for the specific sub-genre of “TV show forensic adventure.” It showed that such games could be competent and faithful, but also creatively stagnant. The Telltale that would later revolutionize interactive drama was still two years away from Sam & Max Save the World and six from The Walking Dead. This game is a fossil of their earlier, less ambitious period.

Conclusion: A Competent, Constrained Investigation

CSI: Crime Scene Investigation – 3 Dimensions of Murder is a game of two, conflicting dimensions. On one hand, it is the most polished and mechanically user-friendly entry in the original CSI adventure trilogy. The freedom to analyze evidence directly in the lab, the 3D object manipulation, the simplified DNA comparison, and the exemplary voice acting are tangible, meaningful improvements that address longstanding player frustrations. It feels more like “doing CSI” than its predecessors.

On the other hand, it is a game utterly enslaved by its own formula. The narrative is predictable, the puzzles are linear and consequence-free, the world is visually sterile, and the core gameplay loop of scanning for hotspots remains a tedious chore disguised as investigation. The absence of any reward for excellence—no unlockables, no narrative branches, no alternate endings—saps the motivation to engage deeply. The PS2 port’s additional case highlights the series’ cynical, compartmentalized approach to content, where a bonus case on one platform is simply repackaged as a sequel on another.

Ultimately, 3 Dimensions of Murder is a shy turn toward modernity. It dragged the CSI adventure series, kicking and screaming, into the third dimension, but it could not—or would not—drag it out of the 1990s adventure game design paradigm. It is a must-play for CSI completionists and an curious, dated artifact for students of licensed game history. For everyone else, it remains a perfectly serviceable, forgettable evening’s distraction that captures the look of the CSI world but only a fraction of its investigative thrill. Its place in history is secure as the game that modernized the series’ presentation, but its failure to modernize its design is the very reason its sequels would soon follow, and eventually, be eclipsed by Telltale’s own later, revolutionary work. It is a solid, sterile, and ultimately safe piece of forensic entertainment.