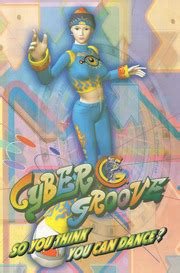

- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Front Interactive

- Developer: Front Interactive

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Music, rhythm

- Average Score: 71/100

Description

Cyber Groove is a high-energy rhythm dance game released for Windows in 2000, inspired by titles like Bust-a-Groove, where players groove to pumping music tracks by following on-screen dance instructions using a included dance mat or keyboard controls. Set in vibrant, cyber-themed environments with crazy graphics, it supports multiplayer dance battles with friends, keeping players moving and entertained late into the night in a festive, party-style setting.

Gameplay Videos

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

ign.com (54/100): Cyber Groove is an interactive dancing game that lets you put on your dancing shoes literally. You can dance or work out or just listen in to the fantastic music on this groovy dance sensation.

Cyber Groove: Review

Introduction

Imagine stepping into a dimly lit arcade in early 2000s Taipei, where the thump of electronic beats pulses through the air, and players stomp rhythmically on glowing pads, their movements syncing with flashing arrows on screen. This was the electrifying world of rhythm gaming, dominated by Japanese imports like Dance Dance Revolution (DDR), but what if that energy exploded onto the PC platform, tailored for a burgeoning Asian computing scene? Enter Cyber Groove, the 2000 Taiwanese dance sensation from Front Interactive that dared to bring mat-based mayhem to Windows desktops. As a game historian, I’ve pored over dusty abandonware archives and yellowed review pages to uncover this overlooked gem—a title that bridged arcade flair with home computing, yet faded into obscurity amid the console boom. My thesis: While Cyber Groove captures the infectious joy of rhythm gaming’s golden age and offers a surprisingly robust workout for solo players, its clunky hardware, dated soundtrack, and niche PC focus relegate it to a curious footnote in video game history, influential more for its cultural adaptation than technical innovation.

Development History & Context

Cyber Groove emerged from the vibrant, underdog Taiwanese game development scene of the late 1990s, spearheaded by Front Fareast Industrial Corporation (operating under the Front Interactive banner). Founded in Taiwan, Front Interactive specialized in edutainment and multimedia titles, but with Cyber Groove, they pivoted to the exploding rhythm genre, aiming to localize the arcade dominance of Japanese hits for PC users. The studio’s vision was clear: democratize dance gaming for the PC-centric markets of East Asia, where console adoption lagged behind robust PC infrastructure. In Korea and Taiwan, PC bangs (internet cafes) were social hubs for gaming, making a keyboard-or-pad-compatible title a smart bet to rival LAN parties and strategy epics like StarCraft.

Released on September 30, 2000 (with some sources citing an earlier January launch in Asia), the game arrived amid technological constraints that defined early-2000s PC gaming. Minimum specs were modest—100 MHz processor, 32 MB RAM, DirectX-compatible graphics, and a 4x CD-ROM drive—reflecting Windows 98/2000’s era, where 3D acceleration was a luxury, not a necessity. The USB dance pad was a bold inclusion, but its “Happy Boy” device ID and limited compatibility (no FireWire support) highlighted the immaturity of peripheral standards. Development likely drew from motion-capture tech for character animations, but budget limitations meant no online features beyond promised song downloads from Front’s now-defunct site.

The broader gaming landscape was console-heavy in the West, with Sony’s PlayStation ruling rhythm pioneers like PaRappa the Rapper (1996) and Bust-a-Groove (1998). In Asia, however, PCs were kings, fueled by affordable hardware and piracy-tolerant cultures. DDR had arcade fever in Japan since 1998, but its console ports were console-exclusive. Cyber Groove filled a void, positioning itself as a PC-native alternative—complete with 21 licensed tracks and 50 downloadable extras—to tap into the growing “dance mat” craze. Yet, it launched just as DDR eyed Western shores via PS2 (2001), dooming Front’s effort to regional obscurity. Patches for bootleg NES pads like Hot Dance 2000 even emerged in hacker communities, underscoring the grassroots, DIY spirit of Asian PC gaming.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Rhythm games like Cyber Groove eschew traditional plots for experiential storytelling, and this title is no exception—there’s no overarching narrative, no branching quests, just a pulsating invitation to lose yourself in the groove. The “story,” if it can be called that, unfolds through ephemeral vignettes: select a song, watch arrows cascade upward, and embody a randomized dancer (a lithe woman in neon, a burly polar bear in shades, or a suited salaryman) who mirrors your steps in the background. These avatars aren’t deep characters with backstories; they’re thematic archetypes representing global pop culture’s fusion—J-pop idols, Western disco relics, and cyber-futurist oddities—emphasizing inclusivity over individuality.

Dialogue is sparse and functional: a chipper female announcer (reminiscent of monster truck rallies) calls out scores, modes, and encouragements like “Perfect!” or “You’re on fire!” in accented English, adding a layer of charm that humanizes the machine. Thematically, Cyber Groove explores the democratization of dance as rebellion and connection. In an era of isolated PC gaming, its multiplayer modes—especially “Together Mode,” where two players share one pad in synchronized chaos—foster physical intimacy and communal joy, echoing Taiwan’s arcade sociality amid rapid urbanization. Underlying motifs of globalization shine through the soundtrack’s eclectic mix: licensed J-pop tracks rub shoulders with German techno and Village People’s “Macho Man,” critiquing (or celebrating) cultural mash-ups in a pre-globalized streaming world.

Deeper still, the game subtly nods to escapism and bodily empowerment. Arrows scrolling from bottom to top symbolize rising energy, pulling players from sedentary screen-staring into kinetic release—a meta-commentary on PC gaming’s physical passivity. Unlocked modes like “Extra” (using diagonals for solo complexity) and “Jam” (amped visuals for sensory overload) deepen this, turning play into a philosophical dance between control and abandon. Flaws emerge in its superficiality: no persistent characters or lore means themes feel emergent rather than intentional, but in 2000’s context, this purity amplified the genre’s core appeal—dance as universal language, unburdened by words.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its heart, Cyber Groove revolves around a deceptively simple core loop: arrows (up, down, left, right) scroll vertically from screen bottom to a static “step zone” at the top, demanding precise inputs via keyboard or the included USB dance pad. Success is measured in hits, combos, and scores, with life bars depleting on misses—fail too often, and the song ends in defeat. This mirrors DDR‘s formula but adapts it for PC with keyboard fallbacks, making it accessible yet mat-optimal for authenticity.

Core modes diversify the experience:

-

Single/Dance Mode: Solo play on four directions, ideal for beginners. Difficulty tiers (from easy pop tunes to frenetic expert charts) gate progression, encouraging replay to unlock secrets like Extra Mode.

-

Double Mode: One player commands two pads (eight directions total), doubling the frenzy for advanced users—think DDR’s solo challenge, but with PC’s multi-monitor potential (though unimplemented).

-

Together Mode: The multiplayer standout, where duos share one pad, weaving through eight arrows in tandem. It demands coordination, turning competition into collaboration, though pad size limits make it a tangle of limbs.

-

Extra Mode (Unlocked): Adds up-left and up-right arrows, evoking DDR Solo ‘s complexity without full 360-degree spins.

-

Jam Mode (Unlocked): No mechanical changes, but layered audio clips and visual flares heighten immersion, rewarding mastery with spectacle.

Character progression is light: no RPG trees, but accumulating scores unlocks songs and modes, fostering a sense of growth. The UI is utilitarian—bright, arrow-filled interfaces with polygonal dancers in the backdrop—but clunky: loading screens drag, and exiting requires obscure key combos (ESC + Pause, or the numeric “0”). The pad’s 10 panels (four arrows plus circle, X, square, triangle for extras, plus ESC/Pause buttons) innovate with diagonals, but reviews lambast its sensitivity; steps often register inconsistently, especially on carpet, leading to frustrating “ghost misses.” Keyboard play feels sterile, a pale shadow of mat stomping.

Innovations shine in customization: song sets by difficulty, two-player versus, and post-patch compatibility with bootleg NES pads via converters. Flaws abound, though— no tutorial beyond basics, and English version bugs (e.g., silent tracks) push users toward the Traditional Chinese build. Overall, the systems excel in workout potential (one reviewer lost pounds via daily sessions), but falter in polish, making it a solid if uneven rhythm engine.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Cyber Groove‘s “world” is a neon-drenched cyber-disco abstraction, less a fleshed-out universe than a vibrant mood board of 2000s club culture. Settings rotate per song genre: pulsating Tokyo-inspired streets for J-pop, garish Vegas lounges for disco, or abstract grids for techno—evoking a global party where East meets West in pixelated harmony. Atmosphere builds through escalation: slow builds give way to arrow barrages, syncing player exertion with on-screen chaos, creating a feedback loop of sweat and euphoria.

Visually, the art direction is a mixed bag of ambition and tackiness. Fully polygonal dancers perform motion-captured routines—fluid hip sways, sharp kicks, even polar bear twirls—that impress for the era’s PC limits, adding vicarious thrill as your avatar nails (or flubs) the groove. Backgrounds, however, are an eyesore: clashing neons, swirling patterns, and Liberace-level ostentation distract more than immerse, aping DDR‘s psychedelia without subtlety. Menus are functional but ugly, with loud start screens and glitchy transitions underscoring the low-budget origins.

Sound design elevates the package, despite criticisms. The 21 core tracks—licensed J-pop, chipmunk-esque Eurodance, and oddballs like “Macho Man”—pump with infectious energy, their beats dictating arrow speed for intuitive flow. Downloadable packs (50 extras, now archived) expand variety, from bubblegum pop to industrial thumps, though repetition grates (e.g., endless “Cartoon Heroes”). Visual-audio sync is tight, with announcer cheers and SFX (whooshes for perfects, buzzes for fails) amplifying tension. Overall, these elements forge an addictive, endorphin-fueled vibe—crazy graphics and pumping music keep nights alive, as promised—but dated tunes and garish visuals age it poorly compared to contemporaries.

Reception & Legacy

Upon launch, Cyber Groove garnered mixed-to-negative Western reception, hampered by its PC exclusivity and limited distribution. IGN’s Vincent Lopez delivered a scathing 5.4/10 in 2001, slamming the “creepy German techno… sung by chipmunks,” hideous backgrounds, and inconsistent pad as a “fish out of water” on desktops—preferring headbanging to Melvins over this “shakier piece.” Conversely, Next Generation‘s Kevin Rice awarded 4/5 stars, praising its embarrassment-free home workout: “No longer an excuse not to play—this is great cardio.” Player ratings on MobyGames hover at 4/5 from scant two votes, with no full reviews, reflecting its cult status among abandonware hunters.

Commercially, it flopped globally—supplies dwindled quickly, and Front Interactive’s site closure sealed its fate—but thrived regionally in Taiwan and Korea’s PC cafes, where bootlegs and patches (e.g., for Hot Dance 2000 pads) extended life. No sales figures survive, but its obscurity is telling: bundled with USB mats, it sold modestly before DDR ‘s 2001 PS2 U.S. debut overshadowed it.

Legacy-wise, Cyber Groove influenced PC rhythm ports indirectly, paving for titles like In the Groove (2006) and StepMania (open-source DDR clone). Its Taiwanese roots highlight Asia’s PC innovation hub, predating mobile groove games like Groove Coaster (2011). Today, it’s preserved via MyAbandonware downloads and archived songs, inspiring retro enthusiasts to mod it for modern Windows. While not revolutionary, it underscores rhythm gaming’s global spread, proving dance mats could thrive beyond arcades—even if on wobbly PC legs.

Conclusion

Cyber Groove is a time capsule of Y2K exuberance: a Taiwanese triumph that imported arcade rhythm to PCs with earnest flair, boasting diverse modes, kinetic progression, and a workout ethos that endures. Yet, its legacy is bittersweet—plagued by hardware quirks, tonal mismatches, and market mistiming, it never grooved into the mainstream. As a historian, I verdict it a worthy niche classic (7/10): essential for rhythm completists seeking pre-DDR Western alternatives, but a cautionary tale of platform pitfalls. In video game history, it claims a small but spirited spot—as the underdog that danced first, even if the world didn’t join in. Fire up an emulator, grab a makeshift pad, and feel the groove; it might just get your blood pumping.