- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Legacy Software

- Developer: Legacy Software

- Genre: Adventure, Simulation

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Courtroom simulation, Detective work, Evidence gathering, Puzzle

- Setting: Contemporary

Description

In this 1997 law simulation adventure from Legacy Software, you step into the shoes of a newly appointed Assistant District Attorney assigned to prosecute the Gatsby diamond jewelry theft. With police having arrested a young co-ed on circumstantial evidence, you must investigate by interviewing fashion photographers, models, and family members, using a digital camera to gather proof, researching similar cases in a law library, and compiling all evidence and witness statements in the ‘Case Constructor’ to prepare for a courtroom trial, all delivered through FMV sequences with real actors and a point-and-click interface.

Gameplay Videos

D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Gatsby Diamond Jewelry Theft: Review

Introduction: The Ambition of the Briefcase

In the mid-1990s, the Full-Motion Video (FMV) craze was in full swing, and publishers dreamed of merging Hollywood spectacle with interactive engagement. Into this volatile landscape stepped Legacy Software’s D.A. Pursuit of Justice, a series that aspired to be more than a mere courtroom drama; it aimed to be a functional, educational simulator of the American prosecutorial process. The Gatsby Diamond Jewelry Theft, released as the second installment in April 1997 (Case 2, or “DA: PoJ Case 2”), stands as a fascinating, flawed, and quintessentially ’90s artifact. It is a game that wears its ambition on its sleeve—or rather, in its meticulously organized digital case files—promising players the gritty, detail-oriented reality of building a prosecution from the ground up. Yet, for all its innovative systems and real-world legal consultation, it is also a product beset by the technical constraints, commercial miscalculations, and pacing issues that would ultimately bury its parent series. This review will dissect the game’s noble vision, its intricate—if clunky—machinery of justice, and its peculiar place in history as a serious sim that was too cerebral for the mainstream and too crude for the hardcore.

Development History & Context: A Costly Experiment in “RealPlay”

D.A. Pursuit of Justice was the flagship title of Legacy Software’s “RealPlay” series, a banner explicitly designed to “intertwine high intensity gameplay with simulated career experience.” This was not a casual claim. The project’s scale was monumental for its era and publisher. According to Wikipedia and contemporaneous press releases, the complete trilogy (all three cases) required 500 pages of script (equivalent to two feature films), featured 57 principal actors, was shot on 20 sets across three weeks of location filming in Los Angeles, and involved six screenwriters under the direction of Richard Marshall. The entire development cycle took approximately one year.

The commitment to authenticity was profound. Legal writing and consultation were provided by Deputy District Attorney Loren Naiman, whose name appears in the game’s credits. This direct pipeline to the California judicial system wasn’t just for flavor; it informed the game’s core mechanic, the “Case Constructor,” and its use of actual penal codes. The ambition even extended beyond entertainment: the game was granted MCLE (Minimum Continuing Legal Education) credit by the State Bar of California, equivalent to 18 units—a singular achievement for a video game. It was also used in Los Angeles high schools via a partnership with public interest law firm Public Counsel to teach about drunk driving (using the first case, The Sunset Boulevard Deuce).

Technologically, it was a showcase for the Windows 95 era. It was one of the first games to bear the “Microsoft Designed for Windows 95” logo and utilized Microsoft DirectX 3. It was a CD-ROM behemoth; The Gatsby Diamond Jewelry Theft alone shipped on three discs, and the full trilogy bundle eventually totaled eight CDs. This physical bulk was a significant barrier to entry and a logistical hassle (frequent disc swaps).

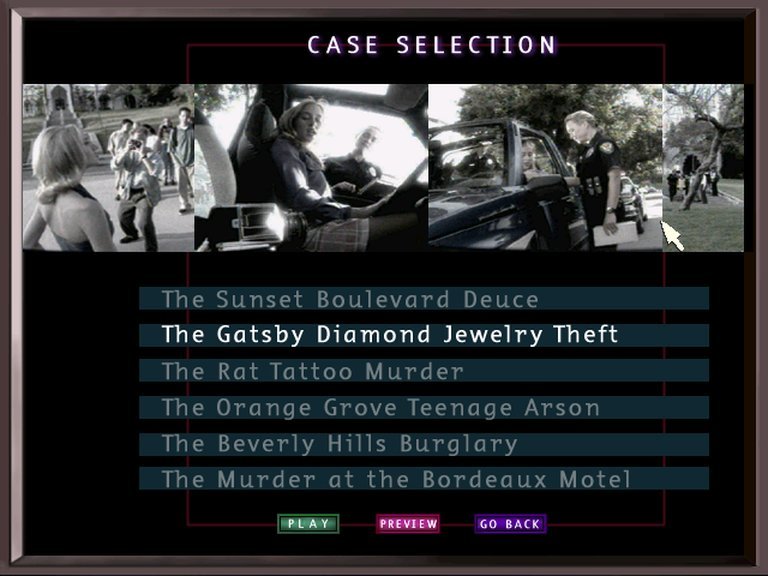

Commercially and corporately, the game’s history is a tale of turmoil. Initially co-published with IBM, Legacy Software paid $400,000 in early 1997 to buy out IBM’s rights. Distribution then shifted to Alpha Software. The game was sold exclusively via online/mail order initially, a risky move that limited its retail visibility, though a later bundled compilation saw broader (though still modest) retail distribution through Activision in 2001. Legacy Software’s financial struggles are starkly documented: the title absorbed $859,424 in company resources in 1998 alone, contributing to the company’s gradual exit from the game industry. Plans for six cases were scaled back to three; the remaining three (The Beverly Hills Burglary, The Orange Grove Teenage Arson, The Murder at the Bordeaux Motel) were never released, victims of the corporate collapse.

Thus, The Gatsby Diamond Jewelry Theft exists as a middle child: conceived during a peak of FMV ambition, produced with startling professional resources, yet born into a market and a company that could not sustain its weighty, niche vision.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Glamour, Circumstance, and the Burden of Proof

The narrative of The Gatsby Diamond Jewelry Theft is a deliberate departure from the visceral crime of its predecessor (The Sunset Boulevard Deuce, a DUI case) and the brutal homicide of its successor (The Rat Tattoo Murder). Here, the crime is one of larceny and deception, set against the backdrop of the Los Angeles fashion and photography scene. The stolen goods are a diamond necklace and a professional camera, purloined from a mansion during a party. The police have made an arrest: a young co-ed (college student), found with the items in her car. The evidence is, as the game states, “circumstantial.”

This premise sets up the game’s central thematic tension: the difference between arrest and conviction. The player, as the new Assistant District Attorney, is not a detective finding the culprit from scratch, but a prosecutor夯实 (strengthening) a shaky case. The plot’s complexity arises not from identifying the unknown perpetrator, but from questioning the obvious one. The co-ed’s possession of the goods is established; the mystery lies in how and why she got them. Was she the thief, or a naive fence? The narrative unfolds through interviews with a cast reflecting its setting: fashion photographers with inflated egos and shady business practices, ambitious models with their own agendas, and family members with protective lies.

The dialogue, delivered by the 57 actors in grainy FMV sequences, is a mixture of legal jargon and industry-specific dialogue. The game’s writers, Max Stanley and Loren Naiman, had to balance authenticity with accessibility. Legal concepts (probable cause, admissibility, mens rea) are introduced, often with on-screen definitions, reflecting the game’s dual identity as both entertainment and a primer. The theme subtly shifts from “whodunit” to “can we prove it?” and, deeper still, to an examination of systemic bias and presumption. The police have a suspect; the fashion world has its own hierarchies and prejudices. The player must navigate not just facts, but the personal motives, alibis, and credibility of everyone involved. The climax in the courtroom isn’t about a shocking twist revelation, but about the methodical dismantling or corroboration of testimony built during the investigation. The victory is procedural, not sensational—a quiet triumph of process over presumption.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Grind of Justice

The gameplay is bifurcated into two exhaustive phases: the Pre-Trial Investigation (four in-game days) and the Trial. This structure is the absolute core of the D.A. experience and its greatest innovation and frustration.

1. The Pre-Trial Grind:

* Exploration & Interview: Using a point-and-click interface, the player navigates static backgrounds (a police station, a law office, a photo studio, a home) to trigger FMV conversations. Characters have multiple dialogue paths, and choosing the right questions is key to uncovering new leads or exposing contradictions. There is a palpable time pressure; each interview, evidence collection, or lab request consumes one of the four allotted days. This is a common criticism noted in reviews like Games Domain’s—the clock can feel arbitrary and punishing, forcing restarts if the player is inefficient.

* Evidence Acquisition: The player is equipped with a digital camera. Certain evidence must be photographed at specific locations, a neat integration of a simple mini-task into the investigation. Finding the right angle or object is a small puzzle in itself.

* The “Case Constructor” & Notebook: This is the game’s genius and its heart. All gathered data—police reports, witness statements (transcripts of interviews), physical evidence photos, and lab test results (ordered via the computer)—are funneled into two key interfaces: a notebook (for reading) and the Case Constructor. The Constructor is a dynamic flowchart where the player must “prove” each legal element of the crime (e.g., Actus Reus: the guilty act; Mens Rea: the guilty mind; Concurrence; Causation). The player drags and drops exhibits and testimonies as “proof” for each element. It is a visual, tactile representation of building a legal argument. You cannot proceed to trial until the Constructor is complete and all elements have sufficient supporting evidence. This transforms abstract legal requirements into a concrete puzzle, making the burden of proof a literal game mechanic.

* Law Library & Research: The player can study “similar case histories,” which are essentially tutorials on specific legal concepts. This reinforces the educational aim but can feel like a chore.

2. The Trial Phase:

* Direct & Cross-Examination: The player puts their own witnesses on the stand, asking a limited set of pre-approved questions (based on what was uncovered in investigation). This is largely a confirmation of your prepared testimony.

* The Real Challenge: Defense & Objection: The meat of the trial is responding to the defense attorney’s cross-examination of your witnesses. The interface presents the defense’s question, and the player must decide to object (and cite the proper legal ground, e.g., “hearsay,” “leading the witness”) or let it stand. Wrong objections are penalized; failure to object to damaging questions can cripple your case. This requires the player to have listened carefully during interviews and understood the rules of evidence.

* Closing Argument & Judgment: After presenting evidence and weathering cross, the player gives a closing argument summarizing the case, and the judge delivers a verdict based on the strength of the presented proof.

Analysis: The systems are deep, deliberate, and punishingly slow. There is no action, no fail states beyond losing the case at the end. The “gameplay” is reading transcripts, managing a digital file cabinet, and solving the meta-puzzle of the Case Constructor. This makes it a pure simulation, closer to a legal version of Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective than any adventure game of its time. Its innovation is in making the preparation the core interactive experience. Its flaw is the grind. The four-day limit is tight for a first playthrough, and the trial’s binary objection system can feel reductive compared to the nuanced investigation. The “score” or performance metric is hidden until the end, a deliberate design choice to keep players focused on justice, not gamification.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Gritty Glamour of FMV Los Angeles

The Gatsby Diamond Jewelry Theft is a masterclass in budget-constrained atmosphere. Visually, it is an FMV game through and through.

* Graphics & Presentation: The live-action sequences, filmed on 16mm (judging by the grain and color bleed), have a documentary, cinéma vérité quality. The sets—the cluttered detective’s office, the sleek but sterile law library, the trendy, dimly lit photo studio—are tangible and period-specific. The fashion world is conveyed through costumes and set dressing more than lush graphics. The grain, compression artifacts, and low resolution (a product of 1997 CD-ROM data limits) are now intrinsic to its charm, but at the time were a technical limitation. Between FMV sequences, the UI is functional, using windows and folders reminiscent of Windows 95, which grounds the experience in the player’s own desktop paradigm.

* Sound Design: The soundscape is minimalist but effective. The ambient hum of a courtroom, the click of a camera shutter, the rustle of papers, and the low, tense music during interviews all serve to punctuate the realist tone. The voice acting, by necessity, ranges from competent to wooden, fitting the B-movie procedural vibe. There is no overblown orchestral score; the music is subtle, synth-based, and moody, allowing the dialogue and sound effects to dominate.

* Atmosphere & Setting: The game’s world is procedural and bureaucratic. The glamour of the Gatsby-esque diamond theft is constantly contrasted with the drab paperwork of the DA’s office. This dissonance is its strength. You are not a hero; you are a clerk of the court, a processor of facts. The setting of Los Angeles is less “sun-soaked paradise” and more “concrete jungle of justice,” captured in the fleeting, often grim, expressions of the FMV actors. The atmosphere is one of meticulous, weary determination.

Reception & Legacy: A Critical Divide and a Shelved Future

Upon its release, D.A.: Pursuit of Justice met with mixed to negative reviews, a pattern reflected in the single critic score listed for The Gatsby Diamond Jewelry Theft on MobyGames: 40% from Computer Gaming World. The CGW review’s terse dismissal—suggesting players buy the superior In the 1st Degree or save for law school—captures the mainstream press’s impatience with its slow, cerebral pace.

However, a more nuanced critical picture emerges from the aggregate:

* Praise centered on its unprecedented realism and educational value. PC Gamer gave it 70/100, GameZone 7.9, and United Gamers Online a remarkable 88%. Publications like Games Magazine and Technology and Learning Magazine awarded it Best New Simulation and Best Home Learning Software. reviewers for The Adrenaline Vault and Game Power/HomePC called it “compelling and entertaining,” noting its ripe subject matter in the age of Law & Order.

* Criticism was universal on two points: pacing and accessibility. PC World’s “caveat emptor” warning and its description as “not a fast-moving” game hits the nail on the head. GameGuru explicitly stated it could be “boring for players used to more fast-paced gameplay.” The limited investigation time and the dense, text-heavy nature of the Case Constructor were cited as barriers. The sheer number of discs and installation hassle were also frequent complaints.

Commercial performance was a disaster. As detailed in Legacy Software’s SEC filings, the game was a significant financial drain. The planned six-case series was cut in half. The company’s exit from the gaming industry by 1998 sealed the fate of the unreleased episodes. This commercial failure is the most defining aspect of its legacy: a bold, well-resourced vision that the market rejected. It was too slow for adventure fans, too dry for FMV fans, and too game-like for pure educational software buyers.

Its influence is thus indirect and niche. It stands as a high-water mark for professional simulation in gaming, predating the more polished Phoenix Wright series by nearly a decade. Its “Case Constructor” mechanic is a direct conceptual ancestor to the evidence-presentation systems in modern detective games. Its MCLE accreditation remains a unique footnote in the history of “games for good.” In the modern retro-revival scene, it is a curiosity and a cult object—praised by sites like Retro Replay for its “cerebral treat” and “distinctive courtroom simulation,” but acknowledged as a product of its time, with “dated” graphics and “cumbersome” disc swaps.

Conclusion: The Unconvincing Yet Historic Testimony

D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Gatsby Diamond Jewelry Theft is not a “good” game by conventional standards of fun, pacing, or technical polish. Its FMV is grainy, its interface is clunky, its tempo is glacial, and its commercial failure is a testament to its misalignment with the 1997 market. To play it today is to engage in an act of historical archaeology.

Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to ignore its radical, if flawed, core proposition: that the drama of the courtroom is not in shouting objections but in the silent, solitary work of building an unassailable case. Its Case Constructor is a stroke of genius, transforming legal doctrine into an interactive puzzle. Its commitment to real-world procedure, from penal codes to the burden of proof, was unparalleled. It is a game that trusts the player’s intellect over their reflexes, a quality that remains rare.

Its place in video game history is secure, if precarious. It is the ambitious, underfunded, and ultimately shelved prototype for the professional simulation genre. It proved that complex, real-world systems could be gamified, but also that doing so required a precision and polish that its era’s technology and market could not always provide. For the historian, it is an essential study in ambition versus execution. For the player, it is a demanding, slow-burn experience that rewards patience with a unique sense of procedural accomplishment. Its verdict in the court of public opinion remains “not guilty” of being a commercial success, but “convicted” of being a fascinating, earnest, and deeply flawed pioneer. Its legacy is not in sequels, but in the scattered ideas it planted—ideas that would take another decade to properly bear fruit.