- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Legacy Software

- Developer: Legacy Software

- Genre: Adventure, Simulation

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Puzzle elements

- Setting: Detective, Mystery

- Average Score: 40/100

Description

In ‘D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Sunset Boulevard Deuce’, players assume the role of a California Assistant District Attorney tasked with proving a DUI case in court within four days. Using first-person interactive movie gameplay with FMV and real actors, you investigate locations like the police station and witness sites, employing a digital camera and legal notebook to research evidence and analyze test results. Build your case in the ‘Case Constructor’ and present it in court through interrogations, objections, and closing arguments to secure a conviction.

Gameplay Videos

D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Sunset Boulevard Deuce Free Download

D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Sunset Boulevard Deuce: Review

Introduction

In the mid-to-late 1990s, as CD-ROM technology unlocked new frontiers for gaming, a peculiar subgenre emerged: the interactive movie. Titles like Phantasmagoria and The 7th Guest promised cinematic experiences on the desktop, blending live-action video with often simplistic puzzle mechanics. It was into this landscape that D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Sunset Boulevard Deuce arrived, not with a bang of supernatural horror, but with the quiet, procedural thud of a gavel. As the first case in a series by developer Legacy Software, it presented itself as a serious, simulation-driven legal drama, casting the player in the role of a California Assistant District Attorney. The premise was tantalizing: forensics, legal research, and courtroom drama, all from the comfort of your 75 MHz Pentium PC. Yet, despite its ambitious scope and noble intentions, this title has faded into relative obscurity, remembered by only a handful of enthusiasts and catalogued by archival sites like MobyGames. This review seeks to excavate this forgotten piece of interactive history, examining its development, dissecting its narrative and mechanics, and ultimately judging its place in the annals of video game legacy. My thesis is that The Sunset Boulevard Deuce represents a fascinating, albeit flawed and ultimately unfulfilled, experiment in simulation gaming—a product of its time that tried to marry the burgeoning FMV craze with a desire for authentic procedural depth, ultimately falling short of its own lofty ambitions due to technical and design constraints that defined the era.

Development History & Context

To understand D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Sunset Boulevard Deuce, one must first understand the environment in which it was created. Released in April 1997 by the developer Legacy Software, the game was part of a deliberate, if niche, business strategy. As detailed on the MobyGames overview, the full D.A. Pursuit of Justice compilation was not immediately available on retail shelves. Instead, Legacy Software opted to sell its three individual cases—including The Sunset Boulevard Deuce—separately for online ordering only. This case, subtitled “The Sunset Boulevard Deuce” and also known as “DA: PoJ Case 1,” was distributed across two CD-ROMs, a significant commitment for a single title in an era where storage space was both a premium and a selling point.

The technological constraints of 1997 are the invisible hand shaping every aspect of the game. The PC Gaming Wiki lists a minimum system requirement of a 75 MHz Intel Pentium processor with 8 MB of RAM, and a recommended spec of a 133 MHz machine with 16 MB of RAM. These were powerful systems for the time, but they were just beginning to handle the demands of full-motion video, especially when combined with other game assets. The game is described as featuring “still shots in combination with FMV scenes, a full musical score and real actors and actresses.” This was the industry’s solution to the technical bottleneck of pure FMV—using static images for navigation and environments while reserving video clips for key events, characters, and narrative moments. It was a compromise that kept the game running but often at the cost of fluidity and immersion.

The gaming landscape of 1997 was a battlefield of genres. First-person shooters like Quake and Duke Nukem 3D were setting new standards for action. Real-time strategy was burgeoning with StarCraft on the horizon. Point-and-click adventures were on the wane, having peaked with titles like The Secret of Monkey Island a few years earlier. It was into this milieu that Legacy Software inserted its procedural simulation. The concept was not entirely new; games like In the 1st Degree (1995) had already explored legal themes, but D.A.: Pursuit of Justice aimed for a higher degree of realism and depth. The developers’ vision, as articulated in the game’s description, was to create a comprehensive legal simulation. They wanted the player to do more than just point and click; they wanted them to work. The vision involved meticulously building a case from the ground up, researching laws in a digital law library, managing evidence, and presenting a coherent argument in court. This was a bold vision for an adventure game, one that leaned heavily into the “Simulation” genre tag it carries on MobyGames, promising a depth that few of its contemporaries in the adventure genre could match.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of The Sunset Boulevard Deuce is presented as a classic “wheels within wheels” detective story, designed to subvert the player’s initial assumptions. The setup is deceptively simple, a narrative hook designed to draw the player into the complex legal web they must navigate. As the game’s description states, it “sounds like a simple DUI (Driving Under the Influence) based upon what the police came up with so far—an open wine bottle, high Blood Alcohol content and several eyewitnesses.” This initial premise is crucial because it establishes the core tension of the narrative: the difference between a police arrest and a successful legal prosecution. The player’s character, a California Assistant District Attorney, is presented not as a maverick detective, but as a professional bound by rules, evidence, and procedure. The story’s central dramatic question is immediately posed: Can you, as the prosecutor, prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a crime has indeed been committed and that the person on trial is the one who committed it?

The narrative unfolds over the course of a tense four-day deadline. This time pressure is a classic thriller mechanic, but here it serves a dual purpose. Thematically, it injects a sense of urgency into a profession that is often slow and deliberative. It transforms the meticulous, often dry, process of legal preparation into a race against the clock, heightening the stakes for the player. The promise that “as your investigation continues, you find it’s not as cut and dry as it seemed at first glance” is the game’s primary narrative promise. The simple DUI is a red herring, a gateway to a more complex conspiracy or misunderstanding. The player must peel back layers, interview witnesses, uncover hidden evidence, and potentially challenge the initial police narrative to discover the “real” story. While the specific details of this deeper plot are not provided in the source material, one can infer that it likely involves mistaken identity, frame-ups, or a crime more sinister than reckless driving.

The characters in this world are archetypes of the legal and criminal drama. There are eyewitnesses whose reliability must be questioned, a defendant whose guilt is presumed but not proven, and a supporting cast of legal professionals and law enforcement figures. The dialogue, delivered by “real actors and actresses” in FMV sequences, was intended to lend authenticity to these interactions. The player engages with these characters not through branching dialogue trees in the traditional sense, but through the lens of a prosecutor’s interview and interrogation. The goal is not to forge a personal relationship but to extract information, assess credibility, and find inconsistencies in testimony—a process that is arguably more true to the character’s role than many more narrative-driven games. This procedural approach to character interaction means that the narrative is less about personal character development and more about the systemic drama of the courtroom itself.

The underlying themes of the game are its greatest strength, even if the narrative execution is limited. Foremost among these is the theme of truth versus perception. The police have gathered enough for an arrest, but proof is a much higher standard. The game forces the player to grapple with this distinction, emphasizing that in a court of law, perception, shaped by evidence and argument, is everything. Secondly, the game explores the theme of professional responsibility. The player is not a hero solving a crime for personal glory; they are an officer of the court with a duty to the law and to society. A successful conviction is a victory for justice, but a wrongful conviction is a profound failure. This weighty responsibility is rarely captured in gaming, making The Sunset Boulevard Deuce a unique, if flawed, attempt to do so.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The gameplay of D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Sunset Boulevard Deuce is a hybrid of several systems, all unified by the first-person perspective and the central goal of building and prosecuting a case. The core loop involves investigation, analysis, and reconstruction. The player is given access to a digital toolkit that includes a “trusty digital camera and legal notebook (computer).” These are not just flavor items; they are the primary interfaces for gameplay.

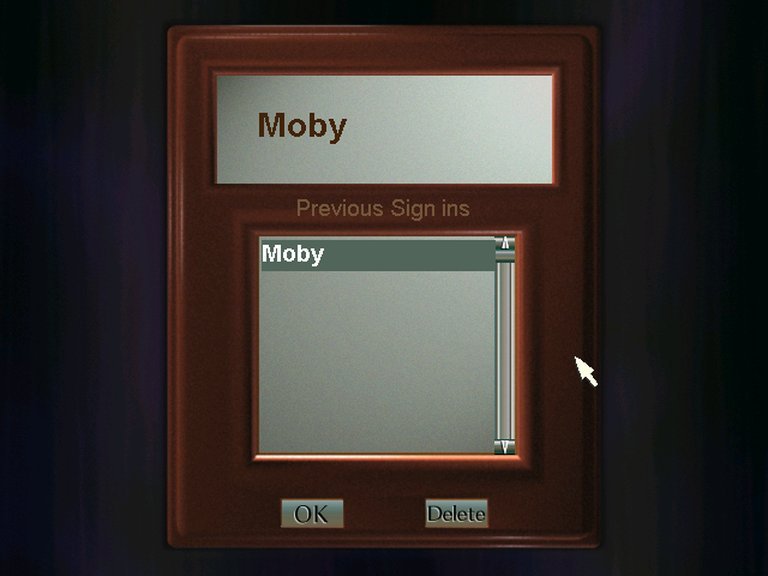

The investigation phase is conducted from a first-person perspective. The player can “travel to various locations (i.e. the police station, law library, locations of witnesses)” by clicking on points of interest in still-shot environments. This navigation is point-and-click, a staple of the adventure genre, but elevated by the game’s simulation elements. At each location, the player’s primary actions revolve around gathering evidence. The digital camera is used to photograph crime scenes, documents, and people. The legal notebook, functioning as an in-game computer, is the player’s hub for case management. From here, the player can “research law, get advice, send evidence to the lab, and analyze test results.” This is where the game attempts to differentiate itself. It’s not just about collecting objects; it’s about processing them.

The “Case Constructor” is the central puzzle-solving mechanic. As described, it is “arranged by departments,” suggesting a structured, almost spreadsheet-like interface where the player must collate all the disparate pieces of information. The player must logically connect the photograph of a wine bottle with the lab’s toxicology report, cross-reference witness statements with alibi evidence, and build a coherent chronological narrative of the events on Sunset Boulevard. This is the intellectual core of the experience, a process of deduction and organization that is far more akin to detective work than the item-based puzzles of traditional adventures.

The culmination of this effort is the court sequence. According to the game’s description, this is where “you will present your case, interrogate witnesses on the stand, make objections and closing arguments.” This is the most ambitious and innovative part of the design. The game attempts to simulate the ebb and flow of a trial. The player’s success or failure is not determined by a simple binary win or lose, but by the strength of the case they have constructed. If the evidence is weak, the arguments are unconvincing, or objections are mishandled, “they’ll go free.” If the player has “done [their] job,” “there’ll be a new inmate in the State Pen.” This creates a high-stakes, meaningful conclusion to the player’s efforts.

The user interface for this entire system was likely a product of its time. The “legal notebook” interface, while intended as a realistic tool, may have felt clunky and unintuitive by modern standards. The reliance on mouse clicks for navigation and interaction, while standard for the era, could become tedious. The game’s score of 40% from Computer Gaming World, which scathingly recommended players “save the rest of your money for the tuition down-payment to Georgetown,” strongly suggests that these systems, while conceptually sound, were executed with a frustrating lack of polish, leading to a gameplay experience that was more work than fun.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world-building of The Sunset Boulevard Deuce is defined by its specificity and its grounding in a plausible reality. Unlike many games of the era that favored fantasy or sci-fi settings, this title places the player squarely in the procedural world of the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office. The locations—a police station, a law library, various witness residences—are not fantastical locales but familiar, institutional spaces. This choice lends the game a sense of gravitas and authenticity. The game’s title itself, The Sunset Boulevard Deuce, is evocative. “Sunset Boulevard” immediately conjures images of Hollywood, glamour, and a certain seediness, a perfect backdrop for a crime story that appears simple on the surface but promises a more complex underbelly. The term “deuce” is clever, likely referring to the suspect’s car (a deuce coupe) or the street itself, adding a layer of local flavor to the case name.

The art direction is a direct consequence of the technological limitations and design choices of the time. The game uses “still shots in combination with FMV scenes.” This hybrid approach creates a unique visual texture. The still shots, which form the basis for exploration, are likely static photographs or pre-rendered backgrounds. They would have served as functional representations of locations rather than immersive, interactive environments. The FMV scenes, featuring “real actors and actresses,” were the game’s primary means of delivering narrative and character interaction. The quality of this footage would have been a key factor in the game’s atmosphere—high-quality video could create a sense of realism, while low-quality, grainy footage (common on early CD-ROMs) would have been jarringly out of place and broken the immersion. The visual style is therefore a dichotomy: the static, exploratory world and the dynamic, narrative world.

Sound design is another critical pillar of the game’s atmosphere. The game description explicitly notes a “full musical score,” which would have been essential for establishing mood and tension during investigation and courtroom sequences. A dramatic score during the trial, a more subdued, investigative theme while poring over evidence, and perhaps a moment of suspense during a key discovery would all work to guide the player’s emotional response. The sound effects, while not detailed in the sources, would have been equally important—the clatter of a gavel, the rustle of papers, the click of a camera shutter. These audio cues would have helped to make the relatively static visual environments feel more alive and responsive.

Ultimately, the art and sound work together to create a world that is more “authentic simulation” than “cinematic thrill ride.” The goal was not to dazzle with cutting-edge 3D graphics but to convince the player that they were inhabiting a real, tangible space, engaging in a real, tangible profession. The success of this endeavor would have hinged entirely on the quality of the acting in the FMV segments and the effectiveness of the audio in masking the limitations of the still-shot environments.

Reception & Legacy

The critical and commercial reception of D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Sunset Boulevard Deuce appears to have been, to put it mildly, underwhelming. The single critical score listed on MobyGames is a damning 40% from Computer Gaming World (CGW), published in their October 1997 issue. This review, as quoted on the MobyGames reviews page, is not just negative but actively dismissive. The critic begins by questioning the value proposition of the entire series: “The full game (the series) comes on eight CDs, and with tax it will cost you about a hundred dollars. How could it possibly be worth that much?” This immediately frames the title as an overpriced niche product.

The reviewer’s disdain is palpable as they advise players to skip the first two cases and go straight to the murder case, only to conclude that even that isn’t worth the effort. “Instead, pick up the much superior IN THE 1ST DEGREE at discount,” they suggest, before delivering the final, cutting blow: “Then, if you’re really serious, save the rest of your money for the tuition down-payment to Georgetown.” This is a masterclass in critical takedowns, implicitly arguing that the game’s simulation of law is so shallow that one would be better off spending the money on a real legal education. This scathing review, though only one data point, likely had a significant impact on the game’s reputation in the enthusiast press at the time.

The commercial success of the game is difficult to quantify, but its release model—sold individually online before a compilation retail release—and its lack of any enduring commercial footprint suggest it did not set the world on fire. It is a historical footnote, collected by only 6 players on MobyGames, a number that speaks to its limited reach and appeal.

In terms of legacy, The Sunset Boulevard Deuce and the D.A. Pursuit of Justice series as a whole represent a fascinating dead end in the evolution of simulation and narrative games. Its influence is subtle, if it exists at all. It predates the more successful legal simulations like Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (which came out in 2001 and took a completely different, more stylized and character-focused approach). However, its ambition to create a detailed, evidence-based legal procedure is a precursor to the more complex and celebrated modern narrative games like Return of the Obra Dinn or L.A. Noire. While The Sunset Boulevard Deuce failed, its attempt to fuse procedural gameplay with a serious narrative carved out a conceptual space that later, more technologically advanced games would successfully inhabit. Its legacy is not one of direct inspiration, but of a failed but noble experiment—a reminder of the era’s frantic and often clumsy attempts to use new technology to create “real” experiences.

Conclusion

D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Sunset Boulevard Deuce stands today as a compelling historical artifact, a time capsule of a specific moment in gaming history when the line between movies and games was being aggressively redrawn. As the first case in Legacy Software’s ambitious legal series, it presented a vision of gaming that was cerebral, procedural, and serious. The game allows players to step into the shoes of a prosecutor, tasked with the monumental challenge of building a case from the ground up, navigating police stations, law libraries, and ultimately, the courtroom. Its narrative, built on the deceptively simple premise of a DUI that unravels into something more complex, holds a core thematic promise about the nature of truth and professional responsibility. Its gameplay systems—the digital camera, the legal notebook, the “Case Constructor”—were forward-thinking attempts to simulate the intellectual labor of detective and legal work.

Yet, for all its ambition, the game is ultimately defined by its failures, most notably as captured in the brutal 40% review from Computer Gaming World. The gulf between its noble intentions and its execution is vast, likely a victim of the technological and design constraints of 1997. The hybrid of still shots and FMV, while innovative, probably resulted in a disjointed and often frustrating user experience. The promise of deep legal simulation likely devolved into a tedious series of point-and-click actions, more work than it was worth, as the CGW review so colorfully argued.

In the final analysis, D.A.: Pursuit of Justice – The Sunset Boulevard Deuce is not a great game, nor is it even a particularly good one by most modern standards. It is, however, an important one. It is a testament to a period of unbridled experimentation, where developers and publishers were willing to fund strange, niche ideas in the hope of finding the next big thing. Its place in video game history is that of a flawed pioneer—a valiant attempt to create a truly “serious” interactive experience that ultimately stumbled. It serves as a fascinating “what if” in the lineage of simulation and narrative games, a reminder that the path to innovation is often littered with ambitious but imperfect projects. For the historian and the enthusiast, it is a curio worth revisiting, not for the quality of the experience, but for the audacity of its vision.