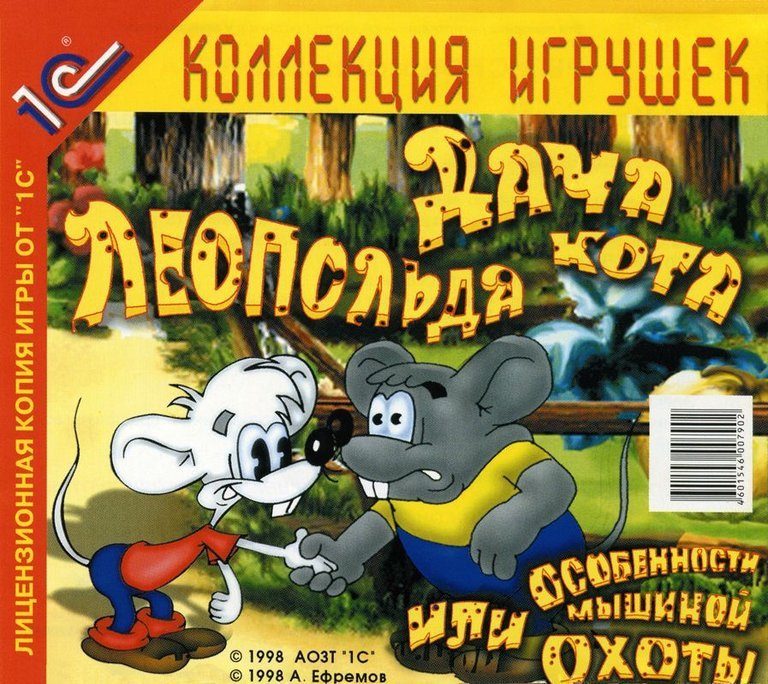

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company

- Developer: 1C Company

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Inventory management, Mini-games, Point and select, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Animated world, Summer cottage

- Average Score: 76/100

Description

Dacha Kota Leopolda ili Osobennosti Myshinoy Okhoty is a point-and-click adventure game set in the world of the Soviet/Russian animation series Leopold the Cat. Players control two mischievous mice, Mitya and Motya, as they navigate through Leopold’s summer cottage, gathering pieces of a destroyed mechanism to build a tool for revenge. The game features puzzle-solving elements, item combination, and a mini-game where players can care for Leopold as a pet. Each mouse has unique abilities, adding depth to the gameplay.

Gameplay Videos

Dacha Kota Leopolda ili Osobennosti Myshinoy Okhoty Guides & Walkthroughs

Dacha Kota Leopolda ili Osobennosti Myshinoy Okhoty: An Exhaustive Review of Russia’s Nostalgic Adventure Gem

Introduction

In the late 1990s, as Russia’s gaming industry tentatively emerged from the shadows of Soviet-era constraints, Dacha Kota Leopolda ili Osobennosti Myshinoy Okhoty (Leopold the Cat’s Summer Cottage, or The Peculiarities of Mouse Hunting) arrived as a quirky love letter to a beloved Soviet cartoon. Developed by 1C Company and released in 1998, this point-and-click adventure dared to adapt Leopold the Cat—a series synonymous with cheeky humor and pacifist morals—into interactive form. But does it transcend its licensing roots to deliver a compelling gameplay experience? This review argues that while the game stumbles mechanically, it shines as a cultural artifact, capturing the charm of its source material while reflecting the growing pains of post-Soviet game development.

Development History & Context

Studio Vision & Technological Constraints

1C Company, now a titan of Eastern European gaming, was still finding its footing in the late ’90s. The studio’s goal was clear: leverage nostalgia for Leopold the Cat, a cartoon that had charmed audiences since 1975, to create a family-friendly adventure. Directed by Anatoly Reznikov (who co-wrote the original cartoon’s screenplay) and spearheaded by programmers Alexander Efremov and Dmitry Korolkov, the team faced significant constraints.

The game was built for Windows 95-era hardware, with minimal RAM (16 MB) and CPU requirements. These limitations shaped its design: static, flip-screen environments and pixel-art sprites reminiscent of early King’s Quest titles. Yet, the team squeezed in innovations like a Tamagotchi-inspired mini-game (Leogochi) and dual-character puzzle-solving—ambitious for a budget title.

The Gaming Landscape

In 1998, Russia’s gaming scene was fragmented. Western classics like Monkey Island dominated globally, but local developers leaned on familiar IPs to carve a niche. Dacha Kota Leopolda joined a wave of “Russian quest” games (e.g., Petya and Red Riding Hood), often criticized for clunky design but celebrated for their cultural specificity.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Plot & Characters

The game inverts the cartoon’s premise: instead of playing as the peace-loving Leopold, you control his rodent nemeses, Mitya (the brainy white mouse) and Motya (the brawny gray mouse). Their goal? Rebuild a destroyed schematic to construct a “mechanism of revenge” against the cat. The story is pure farce, dripping with the slapstick mischief that defined the original series.

Themes & Dialogue

Beneath the cartoonish surface lies a subtle critique of petty vengeance. Leopold, now a reclusive TV addict (a nod to post-Soviet disillusionment?), remains an off-screen pacifist, echoing his iconic catchphrase: “Guys, let’s live friendly!” The mice’s antics—from sabotaging Leopold’s TV to rigging traps—underscore themes of futility, as their plans inevitably backfire.

The dialogue, penned by Reznikov and scriptwriters Alexander Efremov and Dmitry Korolkov, mirrors the show’s wit. Mitya’s pompous scheming contrasts with Motya’s dim-bulb enthusiasm, though the lack of voice acting (outside grunts and sound effects) dulls some comedic potential.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop & Puzzles

The gameplay revolves around item collection, environmental puzzles, and character switching. Mitya handles intellectual tasks (e.g., reassembling a bicycle with a wrench), while Motya brute-forces obstacles (e.g., lifting heavy objects). Puzzles range from logical (combining items to fix a well) to frustratingly opaque (shooting a painting to retrieve a hidden hammer—a notorious pixel-hunting moment).

Innovations & Flaws

The dual-character system anticipates later classics like Broken Age, but clumsy execution mars it. Players lamented the tiny interactive zones and inconsistent cursor feedback. Meanwhile, the Leogochi mini-game—a Tamagotchi clone where you care for a digital Leopold—feels tacked-on, though it nods to late-’90s trends.

UI & Progression

The interface is minimalist: a bottom-bar inventory and a save system with multiple slots. Yet, sluggish screen transitions and limited animations (characters “slide” between frames) betray the era’s technical limitations.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Visual Design

The art team, led by Dmitriy Lazarev, faithfully recreates the cartoon’s aesthetic. Leopold’s cottage bursts with whimsical details: a barking-dog painting that licks the screen, cluttered bookshelves, and a TV that literally explodes during a mini-game. The mice’s animations—particularly Motya’s exaggerated flexing—channel the source material’s physical comedy.

Atmosphere & Sound

Sound designers Vladimir Oryol and Andrey Korinskiy layer the world with chirpy melodies and goofy sound effects (e.g., springs boing-ing, Leopold’s muffled TV chatter). Though repetitive, the soundtrack evokes the cartoon’s playful tone.

Reception & Legacy

Initial Reception

The game earned mixed-to-positive reviews domestically, with an average user score of 3.8/5 (per MobyGames). Critics praised its charm but lambasted its obtuse puzzles. One Russian reviewer noted: “A warm, lamp-like quest… but why must I trial-and-error my way through?”

Long-Term Influence

While not a commercial smash, Dacha Kota Leopolda holds cult status as a relic of Russia’s early gaming experiments. Its IP-driven model presaged later licensed titles like Tanita: Plasticine Dream (2006), and its dual-character mechanic inspired indie devs. Today, it’s a nostalgic curio, often revisited for its historical value.

Conclusion

Dacha Kota Leopolda ili Osobennosti Myshinoy Okhoty is a paradox: a flawed gem that succeeds precisely because of its imperfections. Its pixel-hunting and clunky UI frustrate, but its heart—rooted in Reznikov’s witty writing and Lazarev’s vibrant art—beats with authenticity. For Western players, it’s a fascinating window into post-Soviet pop culture; for Russian gamers, it’s a bittersweet reminder of a transitional era.

Final Verdict

This is not a masterpiece, but it is a vital artifact. Like Leopold himself, the game extends a paw of friendship—flaws and all—to those willing to meet it halfway. For historians and animation fans, it’s a must-play. For others, a charming but uneven curiosity.

“Guys, let’s live friendly!”—Leopold would approve.