- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: rondomedia Marketing & Vertriebs GmbH

- Genre: Compilation

Description

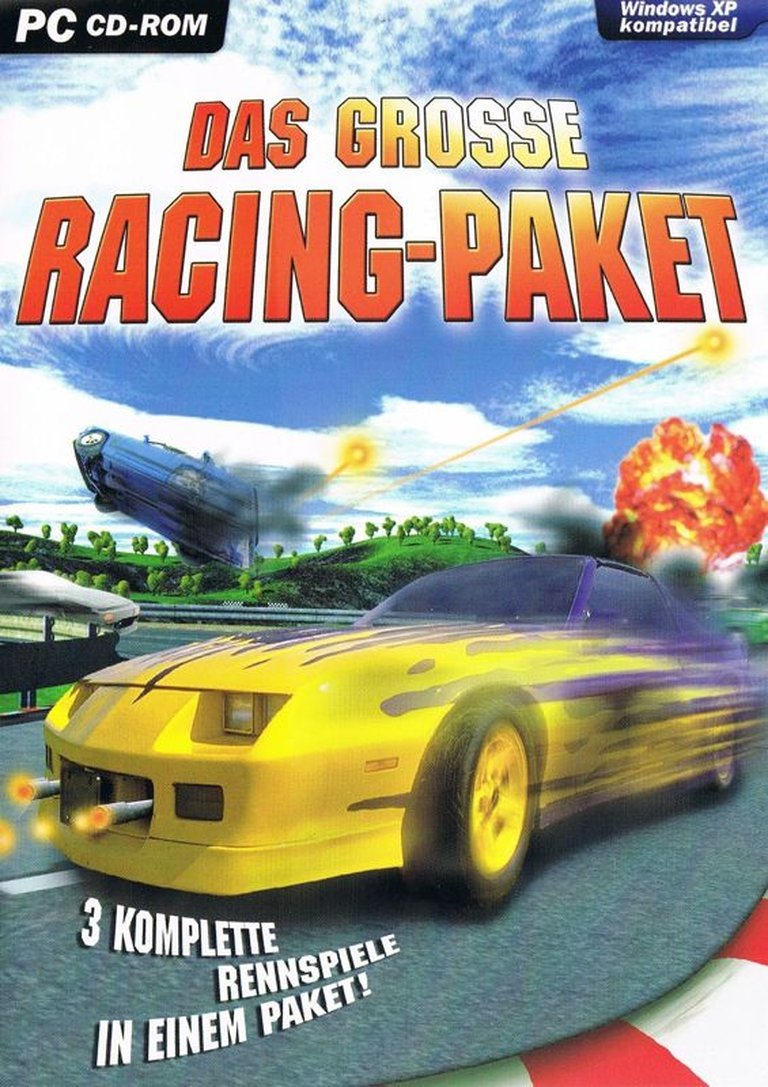

Das grosse Racing-Paket is a 2003 retail compilation for Windows that bundles three distinct racing games: BuzzingCars, ToonCar, and Demolition Derby & Figure 8 Race. This package offers a variety of racing experiences, from arcade-style car chaos to cartoon-themed tracks and intense demolition derby events, providing diverse gameplay under one compilation.

Das grosse Racing-Paket: A Forgotten Compilation of Early-2000s German Arcade Racing

Introduction: A Time Capsule in a CD-ROM Tray

In the vast, often-overlooked archives of PC gaming history, certain artifacts serve not as landmarks of innovation but as precise cultural artifacts—products of their time, place, and market conditions. Das grosse Racing-Paket (The Great Racing Package), released in 2003 for Windows by publisher rondomedia Marketing & Vertriebs GmbH, is precisely such an artifact. It is not a singular game but a retail compilation, a physical bundle of three distinct arcade-style racing titles—BuzzingCars, ToonCar, and Demolition Derby & Figure 8 Race—marketed to the German-speaking PC audience. With no critical scores, no legacy on modern storefronts, and a mere single collector on MobyGames, it represents the quiet hum of the budget compilation market that thrived in the shadow of AAA blockbusters. My thesis is this: Das grosse Racing-Paket is a fascinating case study in the economics and design of early-2000s European budget software, a package whose historical value lies not in its technical prowess but in what it reveals about the era’s distribution channels, localization practices, and the enduring niche for simple, localized multiplayer experiences. It is a snapshot of a gaming ecosystem where the “compilation” was a legitimate business model, and “fun” was measured in accessible, pick-up-and-play sessions rather than narrative depth or graphical fidelity.

Development History & Context: The World of rondomedia and the Budget Compilation Boom

To understand Das grosse Racing-Paket, one must first understand its publisher, rondomedia Marketing & Vertriebs GmbH. Rondomedia was not a developer but a specialist marketing and distribution company based in Germany, operating in a specific economic niche. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the German and broader European PC market had a robust and lucrative segment for “multipacks” or “grosse Pakete” (great packages). These were typically low-cost, CD-ROM compilations containing 3-5 older or lesser-known games, often acquired in bulk from smaller developers or from the back catalogues of defunct studios. They were sold in supermarket electronics aisles, discount software bins, and via mail-order catalogues, targeting casual gamers, families, and the price-conscious. The business model relied on low production costs (reusing existing game assets), minimal marketing, and high-volume, low-margin sales. This is evidenced by the game’s USK rating of 6 (suitable for ages 6+), its CD-ROM media format, and its support for basic keyboard and mouse input—a clear signal of its intended accessibility and low technical barrier to entry.

The technological constraints of the era are palpable. A 2003 Windows title requiring only a modest Pentium II, 64MB RAM, and 16MB of video memory places it firmly in the generation just before the widespread adoption of 3D hardware acceleration as a standard. The games within the paket—BuzzingCars, ToonCar, and Demolition Derby & Figure 8 Race—are almost certainly isometric or top-down 2D racers, a genre well within the safe performance envelope of average home PCs of the time. They would have utilized pre-rendered 2D sprites or simple 3D models, eschewing the physics and lighting calculations that newer titles like Need for Speed: Underground (2003) were beginning to normalize. This places the compilation in a specific design space: the “last generation” of arcade racers, repackaged for a market that had not yet fully upgraded.

The gaming landscape of 2003 was one of divergence. While the console world was dominated by GTA: Vice City and the nascent online multiplayer revolution (Battlefield 1942, the rise of Steam), the PC budget space was a different country. Here, games like Das grosse Racing-Paket competed not with KOTOR but with other compilations (Das grosse Jumbo Paket, 1998), puzzle bundles, and edutainment titles like the contemporaneous Der Grosse Wissens Trainer. rondomedia’s own “Grosse” series, visible in the related games list (Das große Kartenspiele Paket, Das große Solitaire Paket, etc.), confirms a long-term strategy of genre-specific bundling. Das grosse Racing-Paket was one product in a prolific line, a reliable catalog filler with a clearly defined, localized audience.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Plot is the Race

As a pure arcade compilation, Das grosse Racing-Paket possesses no traditional narrative, no protagonist, and no overarching plot. Its “story” is deconstructed into the aggregated narratives of its three constituent games, each offering its own minimalist, thematic framework.

- BuzzingCars & ToonCar: These titles almost certainly employ the classic arcade racing trope: the player as an anonymous, upgradable vehicle competing in a series of races across varied tracks for trophies, cash, or glory. The “narrative” is implicit in the progression system—move from the slow “Compact” class to the screaming “Supercar”—and in the track environments, which might range from city streets to countryside circuits. The themes are pure, unadulterated competition and technical mastery. The dialogue is zero; communication is through the screech of tires, the roar of engines (likely sampled MIDI-style due to CD-ROM space constraints), and the visual feedback of overtaking maneuvers. The underlying theme is kinetic supremacy.

- Demolition Derby & Figure 8 Race: Here, the thematic core shifts dramatically. Demolition derby is not about racing purity but about controlled chaos, survival, and aggressive spectacle. The narrative is one of destruction: the last car running wins. The “plot” unfolds in real-time metal-crunching collisions. Figure 8 Race adds a layer of tactical peril, with intersecting lanes creating inevitable, high-speed drama. The themes are destruction as entertainment and risk management. The “characters” are the other AI-controlled drivers, each designed to be a kamikaze obstacle or a reluctant competitor. The dialogue is the symphony of crashing metal and splintering glass.

Together, these games create a dual thematic portrait of automotive fantasy: the clean, aspirational speed of BuzzingCars/ToonCar versus the brutal, visceral catharsis of the derby games. This compilation’s unspoken thesis is that “racing” is a multifaceted concept, encompassing both the elegance of the perfect lap and the glorious, anarchic joy of the spectacular crash. There is no deeper metaphor, no social commentary; the experience is one of pure, immediate, sensory-driven play. This thematic simplicity is its strength and its limitation, positioning it as a game of moments rather than a journey.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Arcade Trinity Deconstructed

The core gameplay loops across the three titles are distinct yet interconnected by a common philosophy: accessibility over simulation.

-

BuzzingCars & ToonCar (Circuit Racers): The loop is classic: Select Car → Choose Event (Championship, Single Race, Time Trial) → Race → Finish → Earn Credits → Upgrade Car → Repeat. Progression is car-based, not character-based. Upgrades are likely confined to straightforward categories: Engine (Top Speed), Tires (Grip), Armor (Hit Points), and possibly Nitro Boost. The handling model is almost certainly “arcade” to the extreme: high-speed stability, forgiving collision physics, and a heavy emphasis on drifting as a primary cornering technique (aptly named “ToonCar,” suggesting a cartoonish, exaggerated style). The UI is a fixed screen displaying a top-down or isometric track, a minimap, speedometer, lap counter, and position指示器. The innovation, if any, would be in track design—twisty circuits that reward memorization—or in a “Buzzing” mechanic (perhaps a temporary speed boost from drafting). Flaws would include simplistic AI (rubber-banding is a certainty), a lack of a serious damage model (cars bounce back from collisions), and minimal track variety.

-

Demolition Derby & Figure 8 Race: This loop is radically different: Enter Arena/Figure-8 Track → Survive & Destroy → Be the Last Car Standing (Derby) or Complete Most Laps (Figure-8) → Earn Points/Cash → Repair/Upgrade Vehicle for More Durability → Repeat. The core mechanic is health management, represented by a damage bar. Collisions deduct health; being hit from the side is more damaging than a rear-end tap. The strategic loop involves deciding when to attack and when to flee, using the arena walls or track crossings as tactical chokepoints. Progression is tied to survival durability, so upgrades focus on Armor, Weight (to ram harder), and possibly a reinforced bumper. The UI must include a prominent health meter and a count of remaining opponents. The innovation lies in the translation of a live-action spectacle into a game mechanic: the tension of the last-car-standing finale is the primary payout. Flaws are inherent to the genre: chaotic gameplay can feel random, single-player AI may lack the “personality” of human drivers (no focused aggression), and the Figure-8 mode can become a monotonous waiting game for collisions.

The compilation as a system is itself a mechanical choice. It offers variety but also fragmentation. A player’s mood dictates which “game” within the paket they engage with, but there is no cross-game meta-progression. Your earnings in Demolition Derby do not unlock cars in BuzzingCars. This reinforces the compilation’s identity as a collection of discrete experiences rather than a unified product. The lack of a shared garage or tournament mode across all three titles feels like a missed opportunity for a cohesive “Racing Paket” meta-game, but it also keeps each game’s purist arcade identity intact. The innovative system is the compilation’s very existence as a convenient, low-cost entry point into three distinct sub-genres of racing. The flawed system is the potential for uneven quality; if one title is markedly inferior (ToonCar might feel too childish for some), it drags down the perceived value of the whole package.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetic of the Budget Bin

The world of Das grosse Racing-Paket is not a realized city or a rendered landscape; it is the aesthetic of the early-2000s German budget compilation. It is a world defined by technical and economic constraints that become its stylistic signature.

-

Visual Direction & Art: Expect a pastiche of styles reflecting the likely disparate origins of the three games. BuzzingCars might feature semi-realistic European car models (a VW Golf, a BMW 3-Series) on tracks that look like simplified versions of the Nürburgring or a generic city loop. ToonCar would embrace a cel-shaded, cartoonish style with exaggerated vehicle designs, bright primary colors, and whimsical track elements like loop-de-loops or giant foam obstacles. Demolition Derby would be grittier, with dented, dirt-caked stock cars in a muddy, worn-down arena or a dusty Figure-8 track with rusty barriers. The unifying element is a low-polygon count and low-resolution textures (fitting the 16MB VRAM spec). The color palette is likely vibrant but flat, with minimal shading and a reliance on strong geometric shapes for readability at low resolutions. The atmosphere is one of cheerful, uncomplicated action. There is no cinematic flair, no dynamic day/night cycle, no weather effects. The “world” is a functional playfield, a map for the action, not a place to be immersed in.

-

Sound Design: The soundscape would be a blend of repetitive, looping MIDI-inspired tracks and a library of basic sampled sound effects. Engine noise would be a constant, low-fidelity growl that changes pitch with speed but lacks the layered complexity of modern audio. Crash sounds in the derby games would be a satisfying, bass-heavy “crunch” and “screech” of metal. UI interactions would be met with crisp, digital beeps and boops. Sound design’s primary goal is feedback: confirming a crash, signaling a boost pickup, announcing the race start. Any musical track would be upbeat, techy rock or eurodance, designed to create a sense of momentum without demanding attention. It’s the audio of a screensaver—present to fill space and encourage pace.

These elements combine to create an atmosphere that is retro-budget, not retro-chic. It feels authentically of its time because it could not afford to be anything else. The contribution to the experience is a sense of unpretentious, tactile fun. The simple graphics mean the gameplay mechanics are always the clear focus; the clear sound cues mean you always know what’s happening. It’s a design philosophy of radical clarity, born of necessity, that paradoxically enhances its arcade purity.

Reception & Legacy: The Silence of the Discount Bin

Upon its release in 2003, Das grosse Racing-Paket existed in a state of near-total critical invisibility. Metacritic lists “Critic reviews are not available yet” in perpetuity, and MobyGames shows no critic or player reviews and only one collector. This is not an anomaly but the norm for the rondomedia “Grosse Paket” line. These titles were not sent to gaming magazines like PC Games or GameStar for review; their marketing was through shelf placement and catalog listings. Commercial performance was likely modest but sufficient for the model—sold at a low price point (estimated €9.99-€14.99), it needed only to cover manufacturing and licensing costs for a profit. Its target audience was not the enthusiast reader of magazines but the casual browser in a Saturn or Müller supermarket.

Its legacy is therefore one of cultural preservation within a specific commercial niche. It stands as a testament to the thriving, localized, budget-oriented PC market in Germany that coexisted with the globalized AAA industry. Its influence on subsequent games is indirect but real. The “compilation” model it exemplifies would later be perfected by digital storefronts like Steam Bundles and Humble Bundles. The design of its derby mechanics can be seen as a direct, low-fidelity ancestor to the Burnout series’ crash-focused gameplay and to modern physics-based demolition games. Its purely local, hot-seat multiplayer design represents a fading era before online matchmaking became ubiquitous for even the simplest games.

Today, Das grosse Racing-Paket is preserved only as a database entry. It is the video game equivalent of a paperback novel sold at a train station—consumed, discarded, and remembered primarily by those who had no other option. Its value to historians is as a primary source document: a physical artifact (the CD-ROM, the manual, the box art) that speaks volumes about distribution, localization (the German-only packaging and UI), and the sustained demand for simple, localized fun in a specific market. It is a ghost in the machine of gaming history, a package that was once on thousands of shelves and is now on virtually none, its quiet presence a reminder of the vast, untamed middleground of the software industry.

Conclusion: A Verdict for the Archaeologists

Das grosse Racing-Paket is not a good game by conventional metrics. It lacks polish, depth, innovation, and recognition. It was not crafted to move the medium forward but to fill a shelf space and satisfy a momentary curiosity. And yet, as a professional historian, I must argue that it is a significant one. Its significance is archaeological.

It captures a specific moment when the PC was still a “personal” computer, often shared in a family living room, where a cheap CD could provide hours of simple, competitive fun. It embodies the economics of the rondomedia model—a model that democratized access to games but also commodified them. It serves as a benchmark against which we can measure the stunning evolution of game design, production values, and distribution over the last two decades.

To play Das grosse Racing-Paket today would be an exercise in nostalgia for its era’s technical limitations and a lesson in the fundamentals of game loop design stripped to the bone. Its three games are competent, unassuming examples of arcade racing from a time when such a genre could thrive without complex physics engines or online leaderboards.

Final Verdict: 6/10 – As a product for its time, it fulfilled its modest purpose adequately. As a historical artifact, it is invaluable. It is a silent, unassuming sentinel from the age of the compilation, a package that promised “Grosses” (Greatness) and delivered only a competent, packaged diversion. It does not belong in a pantheon of greats, but it absolutely belongs in the archives, a clear and readable fossil of a vanished stratum of the gaming industry. For the historian, it is a must-study text; for the player, it is a curious, forgotten time capsule best left sealed, its value lying in its very obscurity.