Description

Dear Camy is a classic 2D side-view platformer released in 2000 for Windows, where players control the character Camy in single-screen levels filled with challenges. Armed with various bonuses and power-ups, Camy must navigate obstacles, avoid or destroy moving ball enemies, and collect all diamonds in each level to advance, offering straightforward yet engaging freeware gameplay focused on precision and exploration.

Gameplay Videos

Dear Camy Free Download

Guides & Walkthroughs

Dear Camy: Review

Introduction

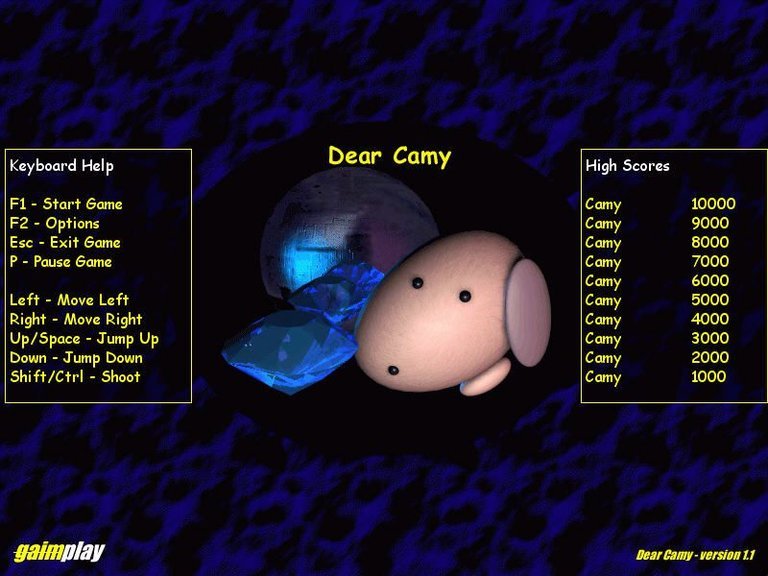

In the nascent days of PC freeware gaming, when dial-up modems hummed and shareware CDs cluttered magazine racks, Dear Camy emerged as a humble yet endearing artifact—a 2D platformer that distilled the genre’s core joys into bite-sized, single-screen challenges. Released in 2000 by the obscure studio gaimplay, this freeware title follows the titular Camy, a quirky, dog-like protagonist with a massive head and stubby feet, as he navigates perilous levels filled with glittering diamonds and menacing bouncing balls. Its legacy is that of a forgotten gem, preserved through abandonware sites and nostalgic forum posts, evoking the era’s DIY spirit amid the rise of flashier console juggernauts like the original PlayStation. Yet, for all its simplicity, Dear Camy punches above its weight in replayable puzzle-platforming, offering a thesis that endures: in an industry now dominated by sprawling open worlds, this game’s unpretentious design reminds us that tight, focused mechanics can deliver pure, unadulterated fun without the bloat.

Development History & Context

Gaimplay, the solo or small-team operation behind Dear Camy, operated out of what appears to have been a modest European base—hinted at by bundled inclusions in Polish and Danish PC magazines like Komputer Świat (2002) and Komputer for Alle (2001). Founded in the late 1990s, the studio embodied the indie ethos of the time, leveraging accessible tools to create shareware titles distributed via downloads from sites like Tucows and their now-defunct gaimplay.com. The game’s lead developer remains anonymous in available records, but the project’s vision seems rooted in classic arcade platformers like Bubble Bobble or early Commander Keen episodes—simple, addictive levels designed for quick sessions on low-end hardware.

Technological constraints defined Dear Camy‘s creation. Built for Windows 95/98 using DirectX 7, it targeted machines with minimal specs: a DirectX-compatible GPU, 3MB of storage, and no need for advanced processing power. The fixed 800×600 resolution and DirectDraw/Direct3D 7 APIs reflected the era’s limitations, where 3D acceleration was emerging but 2D sprites still reigned supreme on PCs. Flip-screen visuals avoided scrolling complexity, ensuring smooth performance on era-appropriate hardware like Pentium II processors. Development likely involved off-the-shelf tools such as Visual Basic for event handling (evidenced by common VB runtime errors in modern runs) and sprite editors for the game’s gradient-heavy, gloomy aesthetic.

The broader gaming landscape of 2000 was a pivotal transition point. Consoles like the PlayStation 2 launch loomed, promising cinematic epics, while PC gaming thrived on freeware and shareware amid the dot-com boom. Platforms like Tucows democratized distribution, allowing indies like gaimplay to reach audiences without big publishers. Dear Camy arrived alongside titles like Half-Life expansions and The Sims alpha buzz, but as freeware, it targeted casual players seeking respite from AAA complexity. Its September 9, 2000, release (per MobyGames, though PCGamingWiki notes a May 21 approximation) coincided with the post-Y2K surge in browser and download-based games, positioning it as accessible entertainment for office workers or kids with magazine demo CDs. Gaimplay’s vision—to craft a series around Camy—evolved with sequels like Camy 2: The Machine (2000) and the 2002 The Camy Collection, which bundled an updated v1.2 (with easier difficulty, more lives, fewer enemies, and refined sprites) alongside a graphical remix, showcasing iterative improvement in a pre-Steam indie scene.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Dear Camy eschews elaborate storytelling for minimalist, gameplay-driven progression, a hallmark of early 2000s freeware platformers where narrative serves as mere window dressing. The plot, if it can be called that, unfolds implicitly: Camy, depicted in player recollections as a bizarre, bodiless canine with an oversized head, two feet, and a gloomy, gradient-shaded design, embarks on a solitary quest through abstract, hazard-filled chambers. No cutscenes, voice acting, or expository text interrupt the action; instead, levels unlock sequentially upon diamond collection, implying a linear adventure of resource gathering amid peril. Dialogue is nonexistent—interactions are limited to on-screen prompts for controls and scores—leaving Camy’s “story” to player interpretation. Is he a lost explorer scavenging treasures in a dystopian void? A heroic mutt evading cosmic threats? The ambiguity fosters a sense of isolation, thematic kin to existential platformers like Limbo, though far simpler.

Character-wise, Camy is the sole focus, his design evoking low-budget charm: a big-headed, footed sprite that jumps and maneuvers with endearing clumsiness, as recalled in Reddit threads where users sketch his “gloomy and grey” form against gradient backdrops. No supporting cast appears; enemies are faceless “moving balls” (bouncing hazards) and occasional bombs, personifying chaos rather than villainy. This sparsity underscores themes of perseverance and ingenuity—collecting diamonds demands precise navigation, mirroring real-world problem-solving in constrained environments. Underlying motifs touch on isolation and futility: endless single-screen levels, no saves, and permadeath upon life loss evoke the grind of early digital life, where progress feels ephemeral. Power-ups (bonuses for temporary invincibility or ball destruction) introduce fleeting empowerment, thematically contrasting vulnerability. In the remix version from The Camy Collection, redone graphics amplify a “cool new style,” perhaps injecting subtle optimism, but the core remains a meditation on solitary triumph over abstract adversity. Critically, the absence of depth is both flaw and virtue; it prioritizes pure mechanics, avoiding the overwrought narratives plaguing contemporaries like Final Fantasy IX.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its heart, Dear Camy revolves around a tight core loop: enter a single-screen level, collect all diamonds while dodging or neutralizing threats, and advance. Controlling Camy via keyboard (arrow keys for movement, spacebar or control for jump/action, as shown in menus), players navigate fixed or flip-screen environments—static rooms that shift panels upon edge-crossing, akin to Chip ‘n Dale Rescue Rangers. The diamond hunt demands platforming finesse: leaping across platforms, timing jumps to avoid falling voids, and using momentum to reach high ledges. Enemies manifest as “moving balls,” erratic bouncers that patrol or chase, requiring evasion or destruction via power-ups like blasters or bombs. Collecting all gems triggers an exit, introducing the next level in a 20+ stage progression (exact count unconfirmed, but series entries suggest escalating difficulty).

Combat is rudimentary yet satisfying—balls can’t be punched directly, but contact destroys them if Camy has a power-up (e.g., a temporary weapon from bonuses). Progression lacks RPG elements; no leveling, just lives (three initially, expandable in v1.2) and scores tracking diamonds and ball kills. UI is spartan: a top-screen HUD displays lives, score, and collected gems, with a pause menu for options (volume, controls display). Innovations shine in puzzle integration—levels often require luring balls into bombs for chain reactions or using wind-like currents for diamond access—adding light strategy to pure platforming. Flaws abound, however: no remappable controls limit accessibility, and the lack of saves means restarts from level one on death, punishing casual play. Single-player only, with direct control feeling responsive on period hardware but sluggish on modern systems without DxWrapper tweaks (which enable VSync for 60FPS and windowed mode). The remix variant refines this with smoother animations and fewer balls, easing the curve, but core systems remain uninnovative—solid for freeware, yet derivative of 2D classics without the polish of Super Mario World SNES ports.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Dear Camy‘s world is an abstract, industrial limbo—single-screen arenas of grey gradients, metallic platforms, and shadowy voids that evoke a derelict factory or cosmic mine. No overarching lore fleshes out the setting; levels progress from basic diamond hunts to complex mazes with bombs and multi-path jumps, building a sense of escalating entrapment. Atmosphere leans gloomy, as per player memories: desaturated palettes with heavy shading create tension, the flip-screen transitions mimicking disorienting teleports in a labyrinthine void. Camy’s design—a headless-torso dog sprite—adds whimsy, his animations (bouncing jumps, idle wobbles) injecting personality into the stark environs.

Visually, the art direction is low-fi 2D sprites rendered in 800×600, with fixed perspectives emphasizing precision over exploration. Gradients on walls and balls provide depth illusion, but pixelation shows on modern displays; the v1.2 update and remix introduce crisper sprites, transforming gloomy greys into stylized neon accents for a “cool new look.” Sound design matches the austerity: royalty-free chiptunes loop minimally, with bouncy platform SFX (boings for jumps, zaps for ball destruction) and diamond chimes punctuating successes. No voice work or ambient layers exist—audio is functional, heightening isolation without immersion. These elements coalesce into a cohesive, if primitive, experience: visuals and sound reinforce the theme of solitary struggle, making triumphs feel earned in their quietude, though lacking the orchestral flair of era peers like Castlevania: Symphony of the Night.

Reception & Legacy

Upon 2000 release, Dear Camy flew under the radar, as freeware often did—bundled in magazine CDs and Tucows downloads, it garnered no major critical coverage. MobyGames lists no critic reviews, with a solitary player rating of 3/5 from one user, praising simplicity but noting dated controls. Commercial “success” was negligible; as public domain freeware, it earned no sales, but gaimplay parlayed it into The Camy Collection (2002, sold via RegNow with Softwrap DRM), bundling updates and sequels for modest indie revenue. Player anecdotes on Reddit (e.g., r/tipofmyjoystick threads from 2022) reveal niche nostalgia, with users recalling its “low-budget” charm and dog protagonist, but also glitches like ball visuals on modern runs.

Reputation has evolved from obscurity to cult curiosity, preserved on sites like My Abandonware (rated 5/5 by three votes) and PCGamingWiki, which documents fixes for Win10+ compatibility (e.g., dx7vb.dll registration for VB errors, DxWrapper for speed/FPS). Its legacy lies in indie perseverance: as the first in the Camy series, it influenced micro-sequels like Camy 2: The Machine, showcasing iterative free-to-paid models pre-Steam. Broader industry impact is minimal—no direct citations in modern platformers—but it exemplifies early 2000s shareware’s role in fostering DIY development, echoing in today’s itch.io titles. Unresolved issues (blinking balls, no widescreen) highlight preservation challenges, yet its availability via Internet Archive ensures endurance as a historical footnote.

Conclusion

Dear Camy distills the essence of early PC platforming into a compact, diamond-chasing delight, its simple mechanics, abstract world, and nostalgic gloom capturing an era when games prioritized fun over grandeur. While lacking narrative depth, innovative systems, or polished production—flaws amplified by age and technical hurdles—it shines as a testament to indie ingenuity, evolving from freeware curiosity to series cornerstone via gaimplay’s Camy Collection. In video game history, it occupies a quiet niche: not revolutionary like Super Meat Boy, but a charming relic for retro enthusiasts willing to tinker with fixes. Verdict: A solid 7/10—play it for the unassuming joy, if not the legacy-shaping ambition; in the vast digital archive, it remains a dear, if diminutive, survivor.