- Release Year: 2020

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: BT Studios

- Developer: BT Studios

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 1st-person

Description

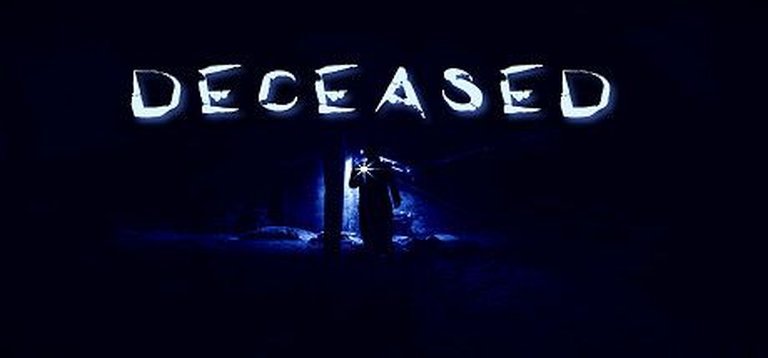

Deceased is an action video game developed and published by BT Studios, released on December 9, 2020, for Windows. It utilizes a first-person perspective with free camera controls, but the provided text does not specify any narrative premise, setting, or gameplay details beyond these technical attributes.

Where to Buy Deceased

PC

Deceased: A Quiet Descent into Obscurity

Introduction: The Ghost in the Archive

In the vast, ever-expanding library of digital entertainment, certain titles exist in a state of perpetual twilight—known to a handful, forgotten by the many, their histories documented only in sparse database entries and the faded memories of a small player base. Deceased (2020), developed and published by the enigmatic BT Studios, is one such title. It is not a landmark of graphical fidelity, a progenitor of a new genre, nor a commercial juggernaut. Instead, it represents something far more common, and in its own way, more poignant: the sincere, solo-developed passion project. Created by a single developer (bilawal14 on community forums), Deceased is a first-person puzzle horror experience set in a specific, grounded locale—a mansion in a Pakistani village—that aspires to atmospheric dread and narrative mystery. This review posits that Deceased is not a game that demands to be placed on a “greatest hits” list, but one that warrants examination as a case study in constrained creation, the aesthetics of low-budget horror, and the fragile lifecycle of an indie title that flew utterly beneath the industry’s radar. Its legacy is not one of influence, but of quiet existence.

Development History & Context: The Solo Mansion

The story of Deceased is, in essence, the story of its creator. BT Studios appears to be a pseudonym for a solo developer, bilawal14, as evidenced by community posts on IndieDB and Steam. There is no studio history, no corporate timeline, no public-facing development diaries. The game’s genesis is described in its own ad copy: “This game is based in my actual village, but the story is fictional.” This is a crucial detail. Unlike the global, mythic scale of many horror games, Deceased‘s setting is personally rooted. The mansion is not a generic “haunted house” archetype but is conceptually tethered to a real, specific place, filtered through a fictionalized tragedy. This imbues the project with a sense of intimate authenticity that larger studios, with their generic European castle or American asylum sets, often cannot replicate.

Technologically, the game was built in Unreal Engine 4, a powerful but complex tool typically associated with high-profile productions. For a solo developer, this choice is significant. UE4 offers stunning visual potential out of the box but also carries a steep learning curve and performance overhead. Deceased’s visuals, as seen in its Steam screenshots, reflect this duality: the lighting and texture work show an understanding of the engine’s capabilities, aiming for a “illustrated realism” (as tagged on AdventureGamers), but the execution is undeniably constrained by limited assets and manpower. The mansion’s architecture feels repetitive, textures are often simple, and animations are rudimentary. These are not criticisms of failure, but markers of its production scale.

The gaming landscape of 2020, when Deceased launched on December 9th, was dominated by major AAA releases and the rising tide of indie darlings on Steam. It entered a market saturated with horror titles—from the polished psychological scares of Silent Hill remakes to the viral phenomenon of Phasmophobia. Deceased had no marketing budget, no publisher hype, and no celebrity cameo. Its context is one of extreme obscurity, competing not with Death Stranding (which shares a thematic keyword but is an entirely separate, universe-apart entity often erroneously conflated in search results), but with thousands of other tiny projects hoping for a moment’s notice in the Steam algorithm.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Personal Apocalypse

Deceased’s narrative is delivered sparingly, through environmental storytelling, scattered notes, and the player’s direct investigation. You are Seth Cooper, an old friend of Dr. Jackson Hofstadter, arriving at the doctor’s imposing mansion to find that Jackson, his family, and all inhabitants have met a “terrible end.” The core mystery is classic Gothic: what happened in this house?

The plot is refracted through “terrifying visions of the past,” which serve as the game’s primary storytelling mechanism. These are not full-motion video cutscenes but likely in-engine scripted sequences or distortions of the environment, meant to piece together the family’s demise. Thematically, the game explores personal grief, scientific curiosity turned to horror, and the lingering stain of violence on a place. The mansion is a character itself—a repository of memory and trauma. The setting in a Pakistani village adds a layer of cultural specificity that is underexplored in the available materials but suggests a desire to move beyond Western-centric horror tropes. The “someone waiting for you” mentioned in the description implies a stalker or entity, a classic survival horror antagonist that transforms the investigative puzzle into a threat of immediate peril.

The narrative’s strength lies in its potential for grounded, intimate horror. The tragedy is not of a world-ending cataclysm but of a single family shattered. The antagonist is likely human (or a human manifestation), tying the horror to domestic, relatable evil rather than supernatural cosmologies. This contrasts sharply with the epic, existential scale of the similarly named Death Stranding and aligns Deceased more with the tradition of P.T. or Silent Hill 4: The Room, where the horror is contained, psychological, and deeply personal.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Weight of Investigation

Deceased is categorized with a confusingly broad array of user tags: Walking Simulator, Immersive Sim, Hidden Object, Puzzle, Exploration, Survival Horror. This taxonomy reveals its eclectic, perhaps unfocused, mechanical identity. The core loop is straightforward: explore the mansion, find keys and clues, solve puzzles to unlock new areas, and piece together the story while avoiding or confronting the threat.

- Exploration & Navigation: The mansion is presented as an “open world” within its confined setting, implying a degree of nonlinearity. Players must navigate dark corridors, often needing a light source. The “darkness that often limits your vision” is a key mechanic, creating tension and forcing careful progression. The free-roaming 3D first-person perspective places a premium on environmental awareness.

- Puzzle & Object-Based Progression: The phrase “pick up key elements, and search for things that may help you escape” points to a classic point-and-click adventure structure translated into 3D. Players collect inventory items, combine them, and use them on environmental objects (e.g., a key for a door, a tool to fix a mechanism). The puzzles are likely contextual and logical within the setting, themed around the mansion’s functions and the family’s life.

- Threat & Tension: The presence of “someone waiting” suggests a stealth or evasion component. The “Survival Horror” and “Immersive Sim” tags hint that the threat may be reactive to player noise or light. The inventory management and resource scarcity implied by “survival horror” could be a factor, though details are absent. The goal is not necessarily combat but escape and discovery.

- Visions & Story Progression: The “terrifying visions of the past” are likely triggered by specific locations or items, serving as both narrative payoffs and potential puzzle hints. This integrates the story directly into the exploration mechanic.

Systemically, the game appears simple, bordering on archaic. There is no mention of complex skill trees, RPG elements, or combat combos. Its innovation, if any, lies in its attempt to fuse the slow, investigative pace of a walking simulator with the tangible object interactions and environmental threats of a survival horror game. The potential flaw is a lack of polish—janky physics, unresponsive controls, or illogical puzzle solutions could easily derail the atmospheric intent. The Steam discussion thread with a user named “illuminatibagul” being “stuck” suggests this is a real possibility, a common pitfall for solo-developed puzzle games.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Haunting of the Specific

The world of Deceased is a single, detailed location: the mansion and its grounds. This is both its greatest limitation and its greatest strength. The art direction aims for “illustrated realism.” The mansion is not a fantastical castle but a large, possibly colonial-era or affluent modern home in a Pakistani rural setting. This specificity is its most compelling feature. The architecture, the decor, the very layout could be imbued with cultural signifiers absent from most horror games. Unfortunately, the available screenshots show generic interiors—wooden floors, old furniture, dim lighting—that could be located anywhere. The promise of its real-world basis remains largely undelivered in the visual evidence available, a common issue when artistic vision outstrips asset creation capacity.

The atmosphere is built on darkness, silence, and sudden auditory jolts. Lighting is paramount, likely using UE4’s dynamic lighting to create long shadows and obscured vision. Sound design would be critical for a solo horror project: creaking floorboards, distant whispers, sudden crashes. The score, if any, is not mentioned, suggesting reliance on diegetic sound and silence to build unease. The “terrifying visions” would require effective visual and audio distortion to feel impactful.

This is a game whose success hinges entirely on the player’s willingness to be immersed in a single, oppressive space. It cannot rely on variety or spectacle. Its world-building is micro, not macro; it asks the player to believe in this one house, this one tragedy. For the right player, that claustrophobic focus can be intensely effective. For others, it will feel repetitive and small.

Reception & Legacy: whispers in the Steam Abyss

Deceased’s reception is a Study in Minimalism. It has no recorded critic reviews on Metacritic or MobyGames. On Steam, as of the latest data, it holds a “Mixed” rating with 52% positive reviews from 17 user reviews (a number that has slightly fluctuated). The player score on Steambase is 46/100 from 28 reviews.

What little commentary exists suggests a game appreciated by a niche audience for its atmosphere and premise but hampered by technical shortcomings. Positive reviews likely praise its creepy ambiance, the engaging mystery, and the charm of a solo dev’s vision. Negative reviews almost certainly cite clunky controls, uninspired graphics, frustrating puzzles, and a short playtime. The presence of tags like “Family Friendly” and “Motorbike” alongside “Horror” indicates a tagging mess, possibly from confused users or the developer’s broad categorization, further hurting its discoverability.

Its commercial performance is effectively invisible. It is not listed in any sales charts. Its “Over 20 million players” figure on some Steam pages is a clear error or system artifact, as the game’s total owner estimates from SteamSpy-like sites are in the low thousands at best. It has won no awards, inspired no known clones, and been referenced in no industry analyses. It exists as a footnote in the database of gaming.

Its legacy, therefore, is one of pure obscurity. It is a game that accomplished what it set out to do for a small audience and then faded. It serves as a data point for the overwhelming volume of games on Steam that exist without a trace in the cultural consciousness. It is the antithesis of a Death Stranding—a game with zero hype, zero controversy, and zero lasting footprint beyond its own store page. Its influence is nil, but its existence is a testament to the sheer volume of creative effort poured into the medium that vanishes without a echo.

Conclusion: The Value of the Unseen

To judge Deceased by the standards of critical darlings or commercial blockbusters is to misunderstand its fundamental nature. This is not a failed Death Stranding; it is a tiny, personal horror game made by one person. Its “place in video game history” is not on a pedestal but in the vast, crowded basement of indie development. It is a curio, a cult object for perhaps a dozen players who found its specific brand of mansions-in-the-fog horror resonant.

Its ultimate worth lies in what it represents: the democratization of game creation. Anyone with access to Unreal Engine 4 and a story can build a world, however small or flawed. Deceased is that world. It is imperfect, likely janky, and almost certainly forgotten. But in its earnest attempt to translate a personal vision of a haunted place into an interactive experience, it participates in the fundamental act of gaming: the sharing of a space, a story, and a feeling. For that, it deserves not a score, but a quiet acknowledgment. It is a ghost of a game, haunting only the most obscure corners of the Steam store, and that is precisely the legacy its creator likely envisioned: a personal nightmare, successfully built and shared, waiting for someone, anyone, to walk through its doors.

Final Verdict: Deceased is a technically limited, narratively sincere, and utterly obscure indie horror game. It is recommended only for the most dedicated hunters of niche, atmosphere-first puzzle experiences who are willing to overlook significant production flaws in service of a unique, location-based premise. For all others, it is a fascinating archival piece—a reminder of the millions of digital stories that flicker briefly and are gone.