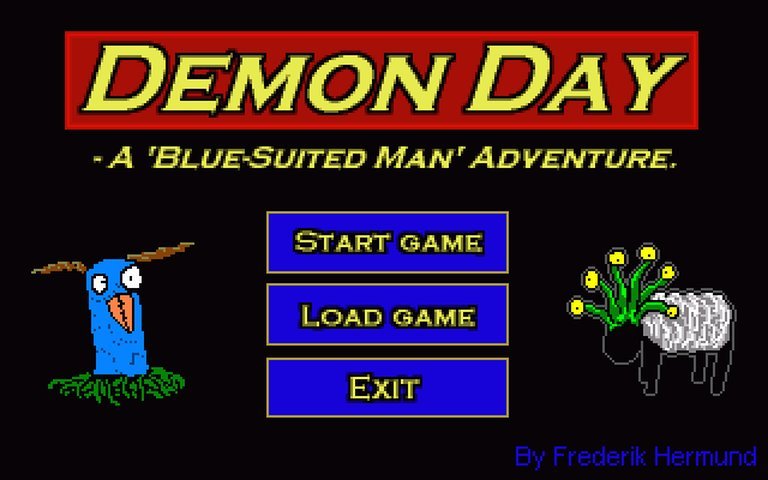

- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: DOS, Windows

- Developer: Frederik Hermund

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other), Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

Description

Demon Day is a humorous point-and-click adventure game set in a suburban environment where the protagonist, after waking from a bizarre dream, must unravel a chaotic plot involving possessed toys, inter-dimensional demons, and eccentric neighbors. Inspired by classic LucasArts titles like Monkey Island and Zak McKracken, it blends detective mystery with horror-comedy, challenging players to solve absurd puzzles and navigate bizarre events to save the day.

Demon Day Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : Introducing Demon Day: a hilarious, medium-length point-and-click adventure that channels the spirit of classics like Zak McKracken, Monkey Island, and Maniac Mansion.

Demon Day: Review

Introduction: A Dream-Induced Day of Chaos

In the vast and often-overlooked archives of early 2000s independent game development, few titles capture the scrappy, heartfelt spirit of the DIY movement quite like Demon Day. Released in April 2004 by a solitary developer, Frederik Hermund, and built with the burgeoning Adventure Game Studio (AGS) engine, this freeware adventure is a love letter to the golden age of LucasArts—specifically the comedic, puzzle-driven titles like Zak McKracken, the Monkey Island series, and Maniac Mansion. Yet, to call it a mere clone would be a disservice. Demon Day carves its own niche through a gloriously absurd premise, a commitment to quirky humor, and a raw, unpolished aesthetic that whispers its creator’s passion. This review will argue that while Demon Day is undoubtedly a product of its technological and developmental constraints, its endearing eccentricities, clever puzzle design, and unwavering commitment to its bizarre vision elevate it from a simple homage to a fascinating cult artifact—a time capsule of indie adventure game development that succeeds precisely because of, not in spite of, its “abominable” qualities.

Development History & Context: The Solo AGS Pioneer

The story of Demon Day is intrinsically linked to the rise of accessible game development tools. In the early 2000s, the Adventure Game Studio emerged as a revolutionary platform, empowering would-be designers with limited resources to create point-and-click adventures in the style of the classics. Frederik Hermund, operating under what would become Creative Spark Studios, was among these pioneers. With Demon Day, he wasn’t just making a game; he was learning the craft, and every pixel and line of code reflects that journey.

Hermund has been refreshingly candid about the game’s origins, famously—or perhaps infamously—labeling it an “early abomination” and his “first internet-released game ever.” This self-deprecating honesty is key to understanding Demon Day. It was created in an era before widespread indie acclaim, before digital storefronts like Steam democratized distribution. Its release as freeware via its own website and archives like the Internet Archive was the norm for the AGS community—a direct connection between creator and player, devoid of commercial pressure. The technological constraints were significant: rudimentary 2D pixel art, limited animation cycles (“jumpy walk-cycles”), and “mysteriously sparse” soundscapes. Yet, these limitations forced creativity. The game’s visual identity, while crude by professional standards, is consistent and expressive, leaning into a cartoonish style that perfectly complements its comedic tone. Demon Day stands as a testament to the “bedroom developer” ethos of the time, where a single visionary could, with enough tenacity and a copy of AGS, produce a complete, distributable game that captured a specific, beloved genre’s magic.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Absurdism in the Suburbs

Demon Day‘s plot is a masterclass in controlled chaos. It begins with an existential jolt: our unnamed hero wakes from a “weird dream” andsteps out for what he expects to be a simple “walk in the park.” This mundane act is the catalyst for a spiraling, nonsensical conspiracy that engulfs his entire suburban existence. The narrative is a patchwork of seemingly disparate, surreal elements: “possessed telechubbies” (the game’s stand-in for innocent toys turned menacing), “demons from other dimensions,” a “friendly neighbour” with his own eccentricities, and a “kid that tyrannizes the local playground.” These are not woven into a grand, epic saga but are instead presented as a series of escalating, bizarre inconveniences that the hero must unravel.

The genius of the story lies in its tonal whiplash and commitment to the absurd. It never pretends to be high fantasy or serious horror. Instead, it operates on the logic of a particularly strange cartoon, where a demonic invasion is just another neighborhood nuisance to be dealt with, often through illogical but hilarious puzzle solutions. The dialogue is the primary vehicle for this humor, packed with witty banter, non-sequiturs, and character-driven comedy. The “tyrannical playground kid” is not a dark, brooding antagonist but a petty, hilarious obstacle, embodying the game’s theme that world-altering threats can manifest as the most trivial, everyday annoyances.

Beneath the slapstick, there is a subtle, warm thematic undercurrent. The hero interacts with his “friendly neighbours,” helping with mundane tasks like watering a pet cactus. This grounding in small-town community life makes the intrusion of the supernatural feel more jarring and, ultimately, more rewarding to resolve. The story is a lighthearted commentary on the thin veil between the ordinary and the extraordinary, suggesting that saving the world might just require talking to everyone on your block and using your inventory items in creatively stupid ways. Its “non-sensical storyline,” as Hermund admits, is not a bug but a feature—a deliberate embrace of the zany, dreamlike logic that defines it.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Classic Loop, Refined

As a point-and-click adventure, Demon Day‘s core gameplay loop is immediately familiar to anyone versed in the genre. Using a mouse, players navigate a series of interconnected 2D screens (the “side view” perspective), interact with objects and characters via a verb menu (typically Look, Get, Use, Talk, etc.), and solve puzzles by combining inventory items and engaging in dialogue trees. The AGS foundation ensures this interface is clean and intuitive, never obtruding on the scene.

The game’s length is described as “medium,” and this pacing is one of its strengths. New locations and gameplay elements are introduced at a steady, confident clip, preventing fatigue while maintaining curiosity. The puzzles are where Demon Day truly shines, aligning with its LucasArts inspirations. They require “skill and a great deal of attention to clues,” avoiding the pitfall of obscure “pixel-hunting.” Solutions are often found in snatches of overheard conversation, environmental details, or the logical (if absurd) application of an item. The praised examples—”outsmarting a tyrannical playground kid” and “disarming a possessed Telechubby”—exemplify this: they demand lateral thinking and engagement with the game’s silly internal logic rather than brute-force trial and error.

Occasional mini-games, such as the cactus-watering task or a “dream-induced maze,” serve as effective palate cleansers, breaking up the core puzzle-solving cycle without derailing the narrative momentum. Hermund’s own critique of “bad humor” might apply to some gags, but the overall puzzle design feels lovingly crafted, offering those gratifying “aha!” moments that define the best adventure games. The “save the day” climax feels earned, a culmination of paying attention to the game’s peculiar rules and clues.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Charming Roughness

Visually, Demon Day is a study in charming limitation. Its “vibrant, cartoonish 2D art style” consciously evokes the aesthetic of early ’90s LucasArts titles, with a color palette that leans into the cheerful and the eerie in equal measure. Character sprites, while simple, are “expressive,” and the animation—though acknowledged as “jumpy”—is used to comedic effect: exaggerated double-takes, surprised stumbles, and over-the-top demon entrances add to the slapstick. Backgrounds, from “sunlit parks” to “shadow-ridden portals,” are “richly detailed” for their scale, making exploration visually engaging despite the low resolution.

The sound design and music, which Hermund describes as “mysteriously sparse and abrupt,” are perfectly in keeping with the game’s overall DIY ethos. There are no sweeping orchestral scores; instead, “upbeat tunes and quirky sound effects” punctuate actions and set moods. These audio cues effectively underscore both comedic and supernatural moments, reinforcing the atmosphere without ever aspiring to production grandeur. The overall sensory experience is one of consistency—the art, animation, and sound all work in concert to sell the game’s unique, off-kilter tone. It feels less like a polished product and more like a vibrant, living storybook drawn by a talented friend.

Reception & Legacy: The Niche Canon

Demon Day’s reception was necessarily muted. Released as freeware by an unknown developer, it existed on the fringes of gaming discourse, primarily discovered through the AGS community portals and archival sites like MobyGames and the Internet Archive. Its “Moby Score” is listed as N/A, and it has been “Collected By” only a handful of players—a stark contrast to the major franchises discussed in the provided (and irrelevant) Devil May Cry source material. Formal critic reviews are absent from the record; its legacy is built on word-of-mouth within retro adventure game circles and retrospective looks from sites like Retro Replay.

Its reputation has evolved into that of a cult curio. It is not remembered as a lost masterpiece but as a charming, representative example of early AGS potential. It showcases how the engine could be used to faithfully recreate a beloved genre’s feel, even with significant technical handicaps. Its influence is likely indirect, part of the swirling ecosystem of freeware adventures that kept the point-and-click spirit alive in the 2000s and inspired a new generation of developers. Where it truly lives on is in the archives—preserved as a historical artifact on the Internet Archive and chronicled on MobyGames. It represents a pivotal, democratizing moment in game development history, where a single person’s “abomination” could find an audience and become a permanent, searchable entry in the historical record.

Conclusion: An Endearing Artifact of Passion

Demon Day is not a game that will reshape the industry or top “Best Of” lists. Its graphics are rudimentary, its animations stiff, its sound sparse, and its writing uneven. By any conventional metric of polish and production value, it is a rough-around-the-edges curiosity. Yet, to judge it solely by those metrics is to miss its fundamental charm and historical significance.

As a piece of interactive storytelling, it succeeds brilliantly. Its puzzles are clever and fair, its humor hits more often than it misses, and its commitment to its utterly bizarre premise is unwavering. It captures the essence of what made classic LucasArts adventures magical: the joy of exploration, the satisfaction of logical (if silly) problem-solving, and the feeling of a world teeming with personality. As a development milestone, it is a perfect case study in the power of accessible tools and singular vision. Frederik Hermund didn’t just make a game; he documented his learning process in a publicly accessible, playable form.

Therefore, the final verdict is this: Demon Day is a flawed but profoundly endearing gem. It is essential playing for historians of the adventure genre and the indie development scene, and a delightful, bite-sized romp for any player with an appreciation for absurdist humor and classic puzzle design. Its place in video game history is secure not as a titan, but as a beloved, quirky footnote—a testament to the idea that a “kinda funny” game made with love, however “retarded,” can carve out its own permanent, peculiar space in the canon. It is, in the truest sense, a game that saves its own day through sheer, unadulterated charm.