- Release Year: 2011

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: UIG Entertainment GmbH

- Developer: Contendo Media GmbH

- Genre: Puzzle

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Match-3, Tile matching

Description

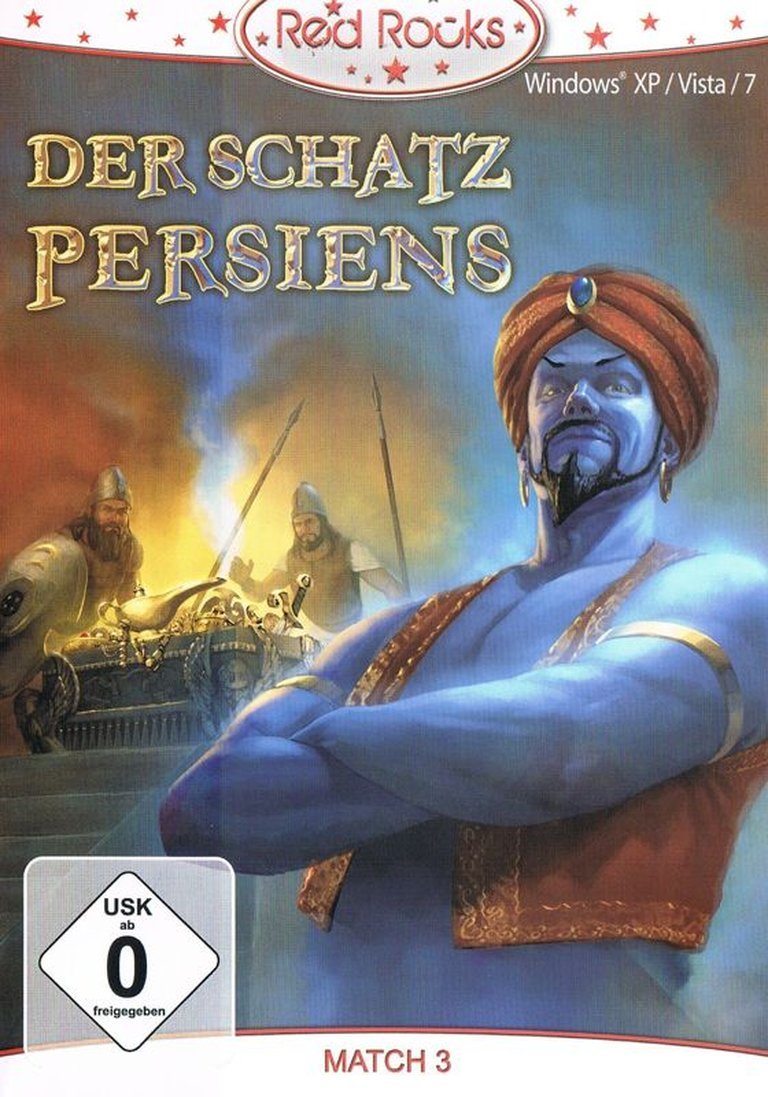

Der Schatz Persiens is a match-3 puzzle game where players align three or more stones to clear them, with larger combinations generating magic stones that remove entire rows or areas. Set across 101 levels featuring over 20 different motifs, the game immerses players in a Persian treasure-hunting theme through varied visual scenes.

Der Schatz Persiens: A Forensic Review of a Forgotten Germanic Match-3 Relic

Introduction: Unearthing the Obscure

In the vast, crowded catacombs of video game history, few titles are as simultaneously ubiquitous and invisible as the mid-2010s casual match-3 puzzle game. They are the digital equivalent of background radiation—constantly present, commercially successful on a low scale, and yet critically invisible. Der Schatz Persiens (English: The Treasure of Persia), released in March 2011 for Windows by the German studio Contendo Media GmbH and publisher UIG Entertainment GmbH, is a perfect case study in this genre’s quiet, mass-produced legacy. It arrived not with a bang, but with a whisper on the retail shelves of German-speaking Europe, destined for the bargain bins and the compilations of airline entertainment systems. This review posits that Der Schatz Persiens is not a forgotten masterpiece awaiting rediscovery, but a meticulously crafted, utterly conventional artifact of its specific time and place. Its significance lies not in innovation, but in its flawless, almost algorithmic, adherence to the Match-3 template as perfected by Bejeweled and codified by Puzzle Quest!. It represents the end of an era where such games could be sold as standalone, full-priced retail products on physical media (CD-ROM) before the mobile and free-to-play deluge rendered them entirely ubiquitous. To analyze Der Schatz Persiens is to perform an archaeological dig on a perfectly preserved, but functionally ordinary, Roman coin—valuable for what it reveals about the mint, not for its rarity or artistry.

Development History & Context: The Puzzle Factory

The Studio: Contendo Media GmbH

Contendo Media GmbH, based in Germany, was a specialist in a very specific niche: “Abenteuer-Spiele” (adventure games) and puzzle titles with a strong Eurocentric, often historical or archaeological, theme. The credits list reveal a tight-knit, recurring team.Lead programmer and designer Michał Rawdanowicz is the linchpin, credited on 53 other games according to MobyGames, indicating a long career in the German budget-game space. Roman Budzowski (Additional/Level Design, 28 other credits) and Christoph Piasecki (Lead) formed the core design brain trust. The art team—Jan-Ove Leskell, Pavel Konstantinov, Olga Onishchenko, Stanislav Pobytov, Kito Sandberg—was a multinational collective (credited on 22+ other games collectively) typical of outsourced European game art in the era, suggesting a pipeline rather than an in-house art department. Konrad Dornfels handled sound and music, and Christian Sanders the text.

The Publisher: UIG Entertainment GmbH

UIG Entertainment was a major German publisher known for its “classics” and budget ranges. Publishing Der Schatz Persiens placed it squarely in the “casual family game” section of German media markets (Media Markt, Saturn), targeting an older demographic less engaged with core gaming press and more with supermarket and department store software sections.

Technological & Market Context (2011)

2011 was a pivotal year. The smartphone boom (iPhone launched 2007, Android rising) was gutting the PC casual market. Candy Crush Saga would not launch until 2012, but the seeds of the free-to-play, level-locked, energy-system model were being sown. Against this tide, Der Schatz Persiens represented a last stand for the traditional, upfront-purchase, PC-based puzzle CD-ROM. Its specs—Windows-only, CD-ROM media—are artifacts in themselves. The “USK Rating: 0 (ohne Altersbeschränkung)” or “without age restriction” confirms its target: the entire family, from children to grandparents, a demographic still reliant on physical media and wary of digital storefronts and microtransactions.

A Formulaic Vision

The “creators’ vision,” as deducible, was not to reinvent the wheel but to perfect a known, profitable, low-risk formula. The title itself—”Der Schatz Persiens”—immediately invokes a lineage: Der Schatz im Silbersee (1993, a classic German adventure based on Karl May), Der Schatz der Azteken, Der Fluch der Osterinsel. This was part of a branded family of “treasure hunt” puzzle games from Contendo/UIG, suggesting a deliberate franchise strategy aimed at a loyal, repeat-buying customer base. The vision was one of efficiency: use a reliable engine (as hinted by Rawdanowicz’s repeated programming credit across titles), apply a new 20-motif visual skin, design 101 levels, and ship.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Treasure That Wasn’t There

Here, the review confronts the fundamental nature of the game. Der Schatz Persiens possesses no narrative. There is no plot, no characters, no dialogue, no text beyond level names and perhaps loading screen tips (the sole credited “Text” by Christian Sanders implies UI and instructional copy). The “Persian” theme is purely aesthetic. The title and the “over 20 different motifs” (screenshots show gemstones on tiled backgrounds with faint architectural or geometric patterns) are a veneer, a setting without a story.

Thematic Analysis: The Absence of Context

This is a crucial departure from the narrative-integrated puzzle games that defined the genre’s evolution, like Puzzle Quest! (2007) or Dungeon Raid (2011). Where those games embedded match-3 into RPG progression and story, Der Schatz Persiens is pure, abstracted mechanics. The “Treasure of Persia” is not a MacGuffin to be sought through a tale of intrigue; it is the abstract reward for completing level 101. The theme functions only as:

1. Aesthetic Dressing: The “motifs” likely include Persian-inspired patterns (arabesques, tilework, perhaps stylized lotus buds or cypress trees) on the game board backgrounds, and gem designs that might be “lapis lazuli blue” or “carnelian red” instead of generic colors.

2. Marketing Positioning: It differentiates the game from Bejeweled or Atlantis in a crowded shelf. “Match stones in Ancient Persia!” has a more specific, culturallyanchored (however superficially) appeal than “Match gems!”

3. Implied Progression: The journey from level to level is implicitly a journey across a map of Persia, from the Zagros mountains to the Persian Gulf, but this is never shown. It is a potential narrative, left to the player’s imagination.

The profound thematic emptiness is, ironically, the game’s most historically authentic feature. It is a pure spiel (game/play), harking back to abstract board games like Mahjongg or Tetris, where the experience is in the systems, not the story. In an era increasingly demanding ludonarrative harmony, Der Schatz Persiens is a stubborn, simple artifact of ludonarrative separation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Unmoving Target

The description is succinct: “Combine three or more stones in a row to make them disappear. Bigger combinations give magic stones that can remove whole rows or areas. 101 levels with over 20 different motifs are included.” This is the entire mechanical canon. Let’s deconstruct.

Core Loop & Match-3 Foundation:

The game is a static, fixed/flip-screen grid (likely 8×8 or similar). The player swaps two adjacent stones to create a horizontal or vertical match of three or more identical “stones” (gems). Matched stones disappear, stones above fall down, new ones generate from the top. This is the Bejeweled loop, circa 2001. There is no gravity physics, no special chain reactions beyond the immediate cascade. It is a deterministic, solvable puzzle in the “rearrangement” style.

The “Magic Stone” Innovation:

The only systemic innovation is the “magic stone” reward for “bigger combinations” (4 or 5 in a row, L-shapes, T-shapes, creating a “cross” or “square”). These function as wildcards or bomb-like items:

* Row/Column Remover: Clears an entire row or column.

* Area/Color Bomb: Clears all stones of a specific color on the board, or a 3×3 area.

This is a direct lift from Bejeweled 2 (2004) and Puzzle Quest! but implemented without any strategic resource management. Magic stones are tools to clear the board faster to meet the level’s goal (usually: clear X number of a specific stone type, or reach a score, within a move limit or time limit). There is no deep strategic layering—you use the magic stone when it’s beneficial, but hoarding it is rarely punished or rewarded.

Level Design & Progression:

Roman Budzowski and Michał Rawdanowicz on level design. 101 levels suggest a gradual difficulty slope. Early levels teach basic matching. Mid-levels introduce specific goals (clear all “emerald” stones, reach 5,000 points). Later levels likely impose tighter move limits and more obstructive board layouts. The “20 different motifs” almost certainly refer to visual themes (background patterns, stone color sets) that change every 4-5 levels, providing superficial variety. There is no evidence of new mechanics being introduced (like locks, blockers, or mud tiles common in later casual games). The progression is purely one of escalating obstacle density and tighter constraints, not new rules. This is 2004-era design in 2011.

UI & Flaws:

With no screenshots of the UI, we must infer. It would be standard: a top bar showing level, score, moves/time remaining, and the level objective. The fixed/flip-screen perspective suggests no scrolling; the board is always fully visible. The primary “flaw” is its utter lack of features:

* No Hint System: A frequent frustration in hard levels, forcing brute-force or external guides.

* No Undo: A critical omission in puzzle design, punishing a single mis-swap with lost progress.

* No Zen/Endless Mode: The game is purely campaign-based (101 levels). No relaxed play.

* Minimalist Audiovisual Feedback: Likely basic click and chime sounds, sparse particle effects for matches. The sound design by Konrad Dornfels is probably functional, not atmospheric.

Innovation?

There is none. Its only conceivable “innovation” is its stubborn, pure form. It is a match-3 game with no gimmicks, no meta-progression, no story, no social features, no daily rewards. It is the genre stripped to its mechanical studs. In 2011, this was not innovative; it was retrograde. Games like Puzzle Quest!, Mystery Case Files, and Diamond Dash had already layered narrative, meta-game, and social mechanics onto the core. Der Schatz Persiens is a deliberate, perhaps commercially safe, rejection of that evolution.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Persian Mirage

Art Direction & Visuals:

The “20 different motifs” are the game’s sole artistic claim to complexity. Given the credits (5 artists, international team), the output was likely competent but generic European budget-game art. The style would be semi-realistic vector art or painted textures, aiming for a “historical” feel but landing in the Uncanny Valley of cultural representation.

* Stones: Gems rendered with simple gradients and highlights. No unique facets or animations.

* Backgrounds: The “Persian” motif. Likely includes stylized representations of:

* Tilework: Geometric kashi patterns.

* Architecture: Silhouettes of iwans or arches.

* Nature: Cypress trees, desert flora.

* Artifacts: Stylized pottery, Lion-and-Sun motifs.

These are static, low-resolution (likely 800×600 native) backgrounds. They provide color palette changes for the gem sets but no atmospheric interaction. The game world is a silent, empty stage. The atmosphere is not one of exploration or mystery, but of sterile puzzle-space. The “Persia” is a postcard, not a place.

Sound Design & Music:

Konrad Dornfels’s work is pure functional audio. Expect:

* Music: Looping, mellow, “exotic”-tinged tracks using synthesized Middle Eastern instruments (oud, ney flute, darbuka rhythms) but with the melodic simplicity of elevator music. It aims for ambiance but achieves generic “mystical bazaar” cliché.

* SFX: Crisp, clean sounds for matching (a satisfying pop or chime), invalid moves (a dull thud), level complete (a triumphant flourish). Magic stone effects might have a deeper whoosh.

The soundscape is designed to be pleasant, non-intrusive, and loopable for hours. It is the audio equivalent of soothing beige.

Contribution to Experience:

Together, these elements create an experience that is competently atmospheric but deeply hollow. The art and sound suggest a theme but the gameplay ignores it entirely. There is no narrative reason for the stones to be Persian; they could be Mayan, Aztec, or Viking (as seen in Contendo’s other titles: Maya: Fight for Jewels, Der Beutezug der Wikinger). This disconnect makes the world feel like a cheap costume. The “atmosphere” is a skin-deep sheen over a cold, mathematical engine.

Reception & Legacy: The Sound of One Hand Clapping

Critical & Commercial Reception (2011):

There is no evidence of any critic or user reviews. The Metacritic and MobyGames pages are empty. This is the definitive reception: absolute critical silence. It sold, we must assume, adequately within its niche. It was not a breakout hit, nor was it a notorious failure. It was shelf-filler. Its commercial life was likely 6-12 months in German retail, followed by inclusion in “1000 Spiele” compilation discs and dusty bargain bins. Its “legacy” is its physical presence in thousands of German households as a forgotten CD in a drawer.

Evolution of Reputation:

The reputation has not evolved because it never had one to evolve. On abandonware sites like My Abandonware, it has a single 5/5 vote (likely from the uploader or a nostalgic fan), with no comments. It is the definition of a “preservation candidate”—a game saved not because it was great, but because it is representative. Its historical value is as a data point.

Influence on the Industry:

Der Schatz Persiens had zero measurable influence. It did not pioneer mechanics (it adopted them late), it did not shift business models (it clung to retail), it did not inspire clones. Its true “influence” is as a capstone. It represents the last gasp of a specific production model:

1. The Regional Retail Puzzle Game: A full-priced, physically distributed, thematically branded match-3 game for a specific language market (German).

2. The Outsourced Art Assembly Line: Its credit list mirrors a model where a core team of 3-4 programmers/designers contracts out art and sound to a global pool—a model perfected by German budget publishers.

3. The Pre-Mobile Template: Its 101-level campaign, move-limit structure, and static board is the direct ancestor of the mobile “level-based” puzzle game, but without the free-to-play hooks. It shows what those mobile games replaced.

It is a fossil of the casual game ecosystem before the smartphone revolution. Its “legacy” is that games like Candy Crush Saga and Royal Match are its evolutionary descendants, having absorbed and monetized the very mechanics it presented so plainly.

Conclusion: A Perfectly Mediocre Artifact

Der Schatz Persiens is not a bad game. It is, by the standards of its genre and its time, a competent, functional, and utterly unexceptional one. It executes the match-3 formula with technical proficiency and zero ambition. Its value, therefore, is purely historiographic.

Verdict: As a game to play in 2025, it offers nothing that cannot be found in superior, free, modern implementations (Bejeweled Stars, Lumines). Its UI lacks modern conveniences, its art is dated, its themes are lazy. As a historical document, however, it is invaluable. It is a Rosetta Stone for understanding a specific moment: the intersection of the Western European budget game market, the tail end of the PC casual CD-ROM era, and the pure, un-monetized, un-narrativized match-3 core loop.

It stands as a testament to the fact that for every Zuma or Puzzle Quest! that pushed the genre forward, there were dozens like Der Schatz Persiens—perfectly serviceable, instantly forgettable, and quietly representative of the vast, unseen middle of the gaming world. It is the game you played on your parents’ PC while waiting for something else to download. Its treasure is not hidden in Persia, but in the archive: a perfectly preserved specimen of a genre at its most conventional, produced at the exact moment before everything changed.

Final Historical Rating: 2.5/5 (as a game) | 5/5 (as an archival artifact).